In light of recent considerations of the science fiction landscape, reflecting on the complex intersection between the real and imagined world in contemporary culture is worthwhile endeavor. The possibilities in speculative fiction challenge barriers formed by legacy and nurtured by practice. The cultural assumptions born from practice feed expectations, which in turn become the basis of action and reaction. Unable to see bodies of color outside prescribed spaces, we don’t question their absence. Indeed, efforts at inclusion can be jarring. Because of innate resistance, it is perhaps no surprise that popular entertainment has been and continues to be a space that offers narratives that question societal expectations and challenge the legitimacy assumed around established identity, power, and community relationships. Whether Jules Verne’s cutting edge stories, which synthesized grounding breaking research in geography, technology and science or Mary Shelley’s imaginative conjecture about contemporary biological research, the creative realm gives voice to the hopes and fears associated with a changing world. In the early twentieth century the assumptions expressed in speculative fiction easily replicated common social and racial prejudice. The center of the future world was invariable Eurocentric, white, male, and heteronormative. Classic characters, many being repurposed for our contemporary superhero cinematic moment play on these expectations.

In the modern context, postwar global transformations realigned the geopolitical landscape and heighten the reality of diversity defining our future. With new economic powers in Africa and Asia re-shaping global commerce and culture, immigration transforming Europe and a majority minority reality in the United States by 2050, the future will be as diverse as it is fantastic.

It is within the milieu that contemporary arguments over the lack of black characters in comics become a window on broader issues. A pop culture correlation to the W.E.B. Dubois versus Booker T. Washington schism over African-American uplift, the contemporary call for African-Americans to create the creative products that realize the diverse vision they want to see is compelling on multiple levels. Yet, much like we have simplified the Dubois/Washington dialogue to facilitate an antagonistic framing, the process of achieving a diverse creative landscape contemporary science fiction is no easy task. Some voices (and there are many) calling for racial diversity hope to leverage the possibility of public outrage against the potential loss of revenue/prestige/ virtue. Other voices take a different approach. If the dominant system will not provide the visions they want, they will create the change they want to see. Neither path is easy, but in the realm of “create the world you want to see” Brandon Easton has emerged as a clear and consistent voice.

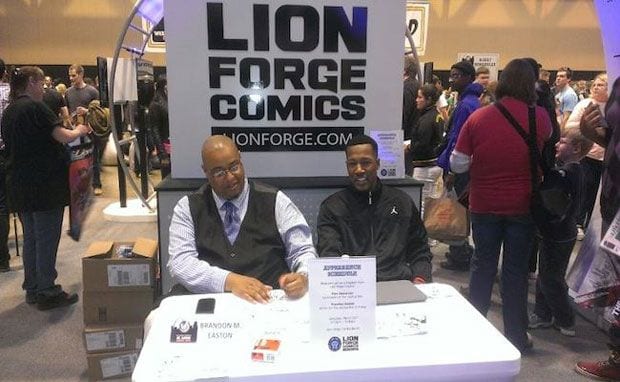

Easton’s personal and professional biography reads like a classic Horatio Alger story. Born and raised in Baltimore, Easton graduated from Ithaca College and earned an MFA from Boston University’s Screenwriting program. A writer with comics and animation credits under his belt, he started his career in 2002 writing Arkanium and Transformers: Armada for Dreamwave Production. During a career lag he sustained himself by teaching in the New York Public School system. Easton made the decision relocate to Los Angeles to jumpstart his career. Near the heart of the entertainment industry, Easton pushed to complete a graphic novel project that became Shadowlaw. Described by one reviewer as offering “a grocery list for all things loved and embraced by different parts of geek culture,” Easton had to persevere through artistic delays to complete the project while juggling the search for new creative opportunities. His efforts paid off handsomely with the publication of Shadowlaw in 2011 and writing for Cartoon Network’s Thundercats reboot in 2012. Easton has continued to rack up writing credits with contributions to the new Armarauders series and freelance contributions to New Paradigm Studios’ Watson and Holmes series. Perhaps more significantly, Easton has emerged a prolific creative voice for Lion Forge Comics. LFC’s stated goal of “acquiring and development content and character franchises” in the comic medium and distributing them over multiple platforms place the company (and Easton) at the center of an evolving digital comic landscape.

All of these things would be enough to keep most people busy, but Easton embarked on an ambitious documentary project focused on African-American creators in speculative fiction. Easton produced, wrote, filmed, and directed the documentary. The project’s description, not surprisingly, points to ambitious goals. The official verbiage makes it clear Easton was to “…explore(s) the thoughts, goals and inspirations of a new generation of Black creators in graphic novels, television, cinema, literature and digital media.” Speaking to broad aspirations and hoping to inspire, Brave New Souls’ goals and its potential impact place Easton at the nexus contemporary dialogues. I reached out to him to delve deeper and learn more.

Creative Journeys

In some ways, your signature creative project is the graphic novel Shadowlaw (Arcana Comics). Shadowlaw sits in a luminal space drawing on myriad pop culture influences. Were you trying to challenge expectations with that work or simply being true to yourself?

The impetus for Shadowlaw was based on my desire to get to the next level in my writing career. In winter 2004, I’d hit a brick wall in terms of industry connections and advancement. I couldn’t get anyone to take a look at my work from Dreamwave and I was told by many of my colleagues that the best way to get the attention of publishers was to create an original graphic novel series and then pray that the sales would be high enough to make an impact in the marketplace.

Shadowlaw was based on a failed screenplay that I wrote while an undergrad. I wanted to combine the elements of Blade Runner and The Lost Boys into something that had never been seen before in comics or cinema. That was a creative challenge because of the ambitious nature of the premise and the fact that I had a lot going on in my life back then. I was a full-time teacher in New York City; a career that required a staggering amount of time as I learned that a teacher’s responsibilities extended beyond the classroom.

How did Shadowlaw educate you on the reality of being a creative professional?

It was a very, very, very painful and exhaustive process. The fundamental lesson I learned was that the more money you have when you begin, the easier things will be in the long run. Not to say that well-financed projects don’t have road bumps, but when you’re struggling to meet an artist’s page-rate and they start drifting away from your series on an emotional and mental level, it is next to impossible to get them back to being excited and engaged.

I went through eight different art teams over the course of six years to get Shadowlaw completed. A few of them were hardcore flakes who didn’t want to do the work, however the rest of them were good guys who just needed to get paid a decent rate. I didn’t have the money to pay them what they deserved and like clockwork they stopped drawing pages.

I realized that asking an artist to complete an entire graphic novel with the promise of pay IF the book sold well would be like working at Wal-Mart and having your boss say that you will get paid only if the store does well during the Christmas rush. It is unreasonable to expect anyone to perform a labor-intensive gig that lasts months at a time to do it for free with no guarantee of compensation.

In contrast to Shadowlaw, you have written comics and animation properties (Transformers and Thundercats) that you have loved since childhood. What is the greatest challenge writing those projects?

The challenge in working in animation (especially with action-adventure series) is reconciling the corporate influence on content. Most of the animated series out there are developed alongside ancillary products like toys, backpacks, bed sheets, etc.

When you’re in a story meeting and you pitch ideas that get shuffled to the side because they aren’t congruent with toy manufacturing, that’s when you realize what product integration truly means. Understand that this isn’t a complaint, but an expansion of your comprehension of how the business operates. It was a very necessary wake-up call as I made the shift from being a fan to a professional creator.

One of the reasons why there’s so much whining and complaining from the geek community in regards to story content is because the fans are very ignorant about the process of how advertising-based commercial entertainment is generated. I truly wish that more people out there would learn how the material is put together so they can understand why studios don’t change the material based on their whims.

You are active on social media and produce two podcasts, Writing for Rookies and The Two Brandons on a regular basis. You are also a consistent voice in forums and on message boards talking about the business in show business. Now, Brave New Souls is a documentary produced, shot, and edited by you spotlighting black creative talent. What will “success” mean to you in this project?

What I want is for these creators to get more attention. Success would mean that genre fans listen to what these folks have to say and then go out and purchase their work — or at the very least — do some research on who these people are and what they’ve created.

Breaking Down Brave New Souls

Brandon Easton’s foray into documentary exploration of contemporary African-American creators joins a host of notable documentaries exploring race and popular culture. Documentaries such as Ethnic Notions (1987) and White Scripts & Black Supermen (2012) have cataloged the powerful impact of popular culture to shape public understanding. Brave New Souls differs from this model by shining the spotlight on upcoming African-American creators and providing an opportunity to understand their challenges in a changing media landscape. In part two of our interview I asked Easton about the project and how it spotlights the creative journey.

You won the 2013 GLYPH Award for Best Writer and this year you won GLYPH Awards for Story of the Year, Best Writer, and Fan Award for Best Work for Watson and Holmes #6 with artist N. Steven Harris. You are one of four minority creators nominated for a 2014 Eisner Award. The GLYPH Awards are associated with the East Coast Black Age of Comics Convention (ECBACC), an organization dedicated to informing the public and celebrating the accomplishment of black comic creators, while Comic-Con International, arguably the biggest comic industry organization, sponsors the Eisner Awards (Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards). I think many people would argue that your success means that the comic industry is recognizing capable creators regardless of color. How does Brave New Souls help clarify the journey facing African-American creators?

The critical establishment within the industry has generally been open to recognizing Black creators. I think of Kyle Baker, M.F. Grimm, Reginald Hudlin and the Love brothers as African-American creators who’ve gotten attention for their work in recent years. ECBAAC’s mission is to highlight the works of Black creators. I agree that the industry recognizes Black creators, but it is much slower to hire Black writers for the big franchises at Marvel or DC.

Brave New Souls clarifies several aspects of the creative journey: 1) how to turn inspiration into action, 2) how to navigate the obstacles that always pop up during the collaborative artistic process, 3) understanding the business side of the entertainment industry from a writer’s perspective and 4) how to market yourself once your intellectual properties are completed.

The participants in the documentary are extremely diverse in terms of social background and approach to craft so viewers will get a wide array of perspectives about what it really means to be a writer in the modern world.

What criteria did you use to pick the creators featured in Brave New Souls?

(laughs) This turned out to be the most controversial aspect of the production.

I live in the Los Angeles area so I picked creators I had access to in the short-term — writers in Los Angeles, San Diego and New York City. I travel to NY several times a year and fortunately for me, I spent most of 2013 on a promotional tour with Lion Forge Comics. This meant I got to interview writers in St. Louis and Chicago during major comicbook conventions in those towns.

There was significant criticism in the form of writers scornfully asking “what about me?” or “what about writers in this city?” or “this isn’t representative of all the Black writers!” What few of those people understood at the time was that I was producing this documentary myself — one-hundred percent of the budget was from my pocket with no investors or donations.

Not only did I finance this project alone, but I didn’t have a production crew. A couple of volunteers flaked on me when I began shooting so this meant I had to operate the camera, record sound, set up the lights and conduct the interviews BY MYSELF. I was a literal auteur.

Those writers who complained that I was ignoring them or not providing a fuller picture of the Black writers in the genre scene were at a loss to explain how I was supposed to fly back and forth across the continent with my limited budget. Not one of those writers offered to cover my flight or travel expenses, not one of those people offered a logical way for us to meet. Not one.

I chose each writer for a specific reason. I believed that having Black writers from television, comicbooks, cinema and mainstream publishers would expose aspiring writers to the realities of the business as well as showcase the careers of these wonderful creators.

Once I narrowed my list to writers I had immediate access to, I considered their level of talent and their future potential. Several of the interviewees already have award-winning careers — particularly novelists N.K. Jemisin and Nnedi Okorafor. Guys like John Jennings, Robert Roach and David Gorden have dual careers as artist/writers with strong reputations as solid storytellers. Then there’s Geoffrey Thorne and Anthony Montgomery who have backgrounds in acting but have made the incredibly difficult switch to a writing career. Tony Puryear and Erika Alexander are Hollywood veterans who have experienced racism and other issues as they’ve tried to push science-fiction properties with non-White leads.

David Steward II is the CEO of Lion Forge Comics and I felt it was beneficial to have a Black entrepreneur reveal their struggle to gain traction in the marketplace as well as explain how they put together a business plan for a company with original intellectual properties. Joe Illidge was a former DC Comics editor (who worked on the Batman titles in the late 1990s) whose experience and insight is priceless. To have creators of this caliber in one place discussing their careers and developmental techniques is like getting an MFA in Creative Writing.

What do their collective efforts say about contemporary speculative fictions produced by African Americans in the 21st century?

The most important statement made is that we exist; that African-American/Black science-fiction and fantasy writers are out there and are capable of creating astonishing stories. I mention this because one of the biggest lies perpetuated by racist fanboy geeks is that Black people don’t read or write speculative material.

Let me explain: over the last 40 years, the sci-fi genre has become part of the cultural DNA of the global entertainment matrix. As recently as the late 1990s, you didn’t see too many Black folks openly participating in the convention scene or the early internet fandom boards (like the Deja Newsgroups, AOL, Prodigy, etc.). Whenever the discussion of increasing non-White-male representation in the genre world was broached, the typical response from White male geeks was that men of color, White women and women of color weren’t fans of the genre so it didn’t make sense to “pander” to a non-existent audience for the sake of “political correctness”.

These arguments persist, run a Google search about author N.K. Jemisin’s experiences with the SFWA members (particularly a racist, sexist writer by the name of Vox Day) or search for the rape and death threats levelled against Janelle Asselin after she dared criticize a comicbook cover that was the result of a casual culture of sexism in the comics biz.

The “good ol’ boy” mindset is a deep-seated construct that informs much of contemporary geek culture. Think about the major geek news hubs and web shows. What do the correspondents look like? Who’s missing? I was watching coverage of the E3 video game conference on Spike TV as well as various mainstream video game news sites and I did not see one Black reporter over that week. I think there might have been some light-skinned Latinas on one of the programs, but that landscape was generally devoid of people of color.

Try getting some of the major genre news sites to cover anything Black. Now that’s another struggle that deserves its own article. All of this has led to the perception that Black people have made zero contribution to the world of speculative fiction.

With so many Black writers creating material, it clearly refutes the lie and reveals the fact that there have always been Black sci-fi fans, but Black fans didn’t show up to conventions in large numbers until the early 2000s across the U.S.

Their efforts also speak to the incredible diversity that exists within the African diaspora. Black people are not a monolithic entity despite constant misrepresentations across mainstream television and cinema. If you examine the body of work from each of the interviewees in the documentary, you’ll find remarkably dissimilar material that is original, thoughtful and unique.

You have been critical of black audiences for not supporting black creators. Yet, arguably, I think some would argue you are blaming the audience for the creator’s failure. What is preventing minority audiences from embracing creators like the ones in Brave New Souls?

This is another extremely controversial subject and I fear this is where I’ve been fully misunderstood. I’m not critical of Black audiences — I’ve been intensely critical of one subset of Black geeks that complain endlessly about the lack of Black-created genre material on the marketplace but then refuse to support said material once they know it exists.

Here’s an example, there’s a Facebook group called Comic Nerds of Color where a good portion of the membership relentlessly gripes about the lack of Black characters in solo series at Marvel and DC Comics. While there are a few members who actively champion our cause, the majority simply won’t acknowledge us. They whine about the lack of Black characters on sci-fi TV shows and movies. Then they’ll complain that there are no Black writers out there for them to support.

Meanwhile, at least 15 independent Black creators with high-quality graphic novels have posted their material there over the last eighteen months and the response has been cold at best. We noticed that these Black geeks ignored our work, while still begging for Marvel and DC to diversify their ranks. It hit me that these folks weren’t comicbook fans, they were Marvel and DC fans — and there is a big difference between those camps.

A true comicbook fan will try new and innovative material; Marvel or DC fans are only interested in corporate superhero properties no matter how much those series frustrate them.

There are several issues at play here, but the two at the forefront are, 1) there’s a population of Black geeks who secretly believe that all Black-created material is inherently inferior, and 2) all attempts at getting this population of geeks to take a chance on Black-created material will be seen as huckstering or “pushing an agenda.” How can anyone make a difference in the marketplace when you’re confronted with this mentality?

Sticking with the comicbook industry model of career advancement, the only way an independent Black writer can get work at Marvel or DC is if they sell tens of thousands of copies of their work on the independent level first, but we can’t sell tens of thousands of copies when you’re dealing with an audience who won’t acknowledge you and/or assumes your work will be subpar without reading a single page.

I spent a year arguing with members of that Facebook group and I’ll never get that time back. I was accused of being a “bitter creator” who was upset that people weren’t buying my work. That wasn’t the case because I’m doing pretty well by all measures for an indie comics writer — but I was disturbed by all the negative assumptions and total disregard for the hard work of Black indie comics professionals.

To speak more to the question, I agree that marketing is the number one problem for any indie comics professional, regardless of race, class or gender. If you don’t have a war chest specifically set up for marketing and promotion, you have to get out there and earn one fan at a time and that takes years. I don’t get upset at fans for not knowing we exist, I got upset because once we let folks know we’re out there, they ignored us and continued to bellyache about what Marvel and DC weren’t doing for Black fans.

In the documentary, you will hear other Black writers discuss the phenomenon of being ignored by Black geeks at conventions and online. This was never about me calling out a section of Black geekdom, these conversations were born from the collective experience of being shunned by our core audience.

There have been and continue to be questions about representation linked to gender and race in comics culture. How does Brave New Souls address these issues?

The documentary doesn’t mention any of the current controversies in the industry, but there is a discussion on the importance of having diverse creators service an increasingly diverse global fanbase. The Earth’s population is mainly Brown, Yellow, Red or Black but the gatekeepers and creators of entertainment are predominantly White. That’s not a criticism of anyone as there are thousands of incredibly imaginative and talented White writers out there but we’re saying that they’re not the only ones capable of entertaining the masses.

One of the conversations that kept popping up was the role of the gatekeeper in publishing and in Hollywood. Author N.K. Jemisin discussed this at length but the sound quality of the recording resulted in us cutting most of her interview, however she raised several excellent points about who has control of the flow of material from the submission editors up to the publishers who can greenlight a book deal. If the publishing industry gatekeepers tend to be White women from upper-middle class environments who have limited exposure to African-American people and culture, the idea of Black science-fiction is as alien to them as the characters in the manuscript. The traditional publishing world is as White as the mainstream American comicbook industry and the lack of Black editors in both arenas has led to extreme exclusion by accident or design.

Several creators discuss this situation in the documentary. We don’t believe there’s a conspiracy at work, but there’s an unofficial policy of cronyism/nepotism that reinforces a culture of racial exclusion. Most of the editors are White guys and their closest friends and colleagues are White guys so who do you think will get the call whenever there’s an open slot for a writer?

Again, no one is saying there is a deliberate conspiracy to exclude Black writers from the industry, but it looks terrible when the same five or six White guys get to write just about everything at Marvel or DC and the numbers stink but these guys get to work on other high-profile titles regardless of their past sales record. When you hear the powers that be say that they hire and retain writers based on sales and some of these folks are selling under thirty-thousand or twenty-thousand copies at a time, you wonder why they don’t look for new voices to inject fresh ideas into their properties.

Everybody knows this is a concern, but there’s been little movement to correct the imbalance.

What did you see as the biggest challenge facing black creators when you started this project? Have your views evolved based on this experience?

Marketing and marketing — that’s the only true challenge. We have to increase our awareness among genre fans across the board. That’s the only way we can know if our products can resonate with a mass audience but as long as we’re scrambling along the fringes of the industry no one will take us seriously.

Following up on that idea, give fans two things they can do create change?

Great question. There’s a brother named David Walker (writer of Number 13 from Dark Horse Comics) who published an essay on his blog about how genre fans give the major companies too much free advertising in the form of retweets and Facebook posts. These corporations have hundred-million dollar marketing budgets but geeks (including myself) love to post pictures, trailers and interviews regarding mainstream comicbook movies, novels, video games and web series.

David’s point was that we should stop giving the corporations so much free marketing when there are deserving independent creators out there needing a signal boost on social media just so they can make a few dollars.

The first thing fans can do is share and hype links for indie creators and their products. The simple act of retweeting or sharing a link or photo on Tumblr and Instagram can expose a creator to a larger audience overnight. On Facebook, one person can post a link to multiple groups or tag a bunch of friends on a photo within seconds. If every genre fan spent one day a week hyping an indie project on social media, you would see a significant shift in perception and awareness.

The other thing fans can do is stop at our (Black indie creators) booths at conventions and talk to us. Even when we attempt to engage folks at conventions, a lot of Black fans will ignore us and some go out of their way to pretend we don’t exist. It’s not even about making a sale, most of us have free material to give out and we would love it if you would take a flier, postcard or ashcan. Word of mouth is extremely important for the growth of a writing career. If no one is talking about you, then you don’t exist in the marketplace. That’s just the way it goes.

So if we had fans share our materials on social media and take a moment to look at our work at conventions, you’d see a slow, but steady, change in industry awareness.

What is the question no one asks, but you want to answer?

No one discusses body shaming in comics. We have been inundated with unrealistic images of women and men for almost one hundred years and we don’t really discuss how this affects the body image of comicbook fans. We do discuss the inherent sexism of how women are drawn, but we never really have a serious discussion about what this does to the psyche of men and their expectation of themselves and women.