In 1989, you would’ve really had to stretch your imagination to believe that Merge Records would still be around a quarter of a century after it began as an outlet to self-release Superchunk 7″ singles because no one initially would. And certainly no one could’ve forecasted that Merge would become as influential as it is now, going from underground trendsetter to the home of Billboard chart-toppers, Grammy awardees, and indie legends. But that’s exactly where Merge stands today as it celebrates its 25th birthday this week with a festival taking place in its homebase of the Research Triangle in North Carolina.

Apropos of the label’s own backstory, unlikely success stories have been Merge’s specialty. Who knew that Merge’s first breakthrough into the popular consciousness would’ve come with what seemed at the time to be an overly ambitious, gimmicky, unwieldy three-CD boxset –the Magnetic Fields’ 1999 opus, 69 Love Songs? Who expected Spoon would go from exiled major-label never-weres to a consistently charting act after Merge rescued the now venerable Austin band from the alt-rock scrapheap? And who would’ve predicted that a heretofore unknown collective from Montreal would turn into the current generation’s U2 and Springsteen all rolled into one when Merge released the Arcade Fire’s Funeral in 2004? Yet all that really happened over the last two-and-a-half decades, which is why Merge has become a model franchise that aspiring indies and restructuring majors alike are patterning themselves after.

From the outside looking in, the secret to Merge’s success actually seems rather simple, yet something that can’t be replicated or imitated: a sense of community. That’s the core principle that seems to have guided Merge and Superchunk founders Laura Ballance and MacMcCaughan in their artistic investments and business endeavors — as Ballance puts it in the video above, Merge’s basic philosophy is “to be nice to people and to be fair.”

In the most basic sense, that spirit of camaraderie and bonhomie informs everything the label has done, right down to Ballance and McCaughan’s initial aim for Merge to preserve and grow its own local musical community. That’s something Merge’s catalog has stayed true to through thick and thin, tracing the lineage of the North Carolina indie-rock from early label stalwarts like Polvo and Pipe to newer voices such as Mount Moriah and Spider Bags. But that idea of community has become at once more intangible and more substantial as Merge has aged. It’s what has tied Merge to the New Zealand underground for over two decades, its commitments never stronger than when the label rallied the troops to make a benefit album for Chris Knox after his stroke. It’s the reason why Merge has been a refuge for so many esteemed acts looking for a new home — from Bob Mould to Teenage Fanclub, from the Buzzcocks to Carrie Brownstein in Wild Flag — who, in turn, have produced some of their best work after that was supposed to be behind them. And it’s really the thread that stitches together a catalog that’s broad and diverse, defined by a shared ethos more than a sound.

To mark the silver anniversary of Merge Records, PopMatters has come up with a list of 25 essential albums from the label. While one could almost compile such a best-of list with just Superchunk, Magnetic Fields, and Spoon albums, we decided to not to double-dip from any band’s discography to give a broader, better cross-section of what Merge has to offer. So yeah, we know the list to follow doesn’t start with Merge’s first and perhaps defining album — Superchunk’s singles comp Tossing Seeds (1992) — nor is Arcade Fire’s The Suburbs, Merge’s best-selling and only Grammy-winning disc, on here. But actually, that seems only in keeping with the spirit of a label that plays no favorites if only because every release is treated like a favorite.  Arnold Pan

Arnold Pan

Polvo

Today’s Active Lifestyles (1993)

Polvo was never destined to have a wide appeal; the band’s fondness for shifting time signatures and unconventional guitar tunings meant that it could aim to be a semi-mainstream curiosity, at best. Still, when they first appeared, their take on noise rock was unlike anything that any band was attempting at the time, and 1993’s Today’s Active Lifestyles is still the most refined, sharpened take on what they did. The album seems like neither fish nor fowl: too dissonant and off-kilter for more conventional indie rock, yet not hard and twisted enough for fans of the “math rock” genre that Polvo founded, then disavowed. Yet, the album’s singular place in Polvo’s discography and in indie rock makes it all the more remarkable.

Ash Bowie always seemed to prefer to let his guitar talk for him, and he might be better for it. Bowie’s work on Today’s Active Lifestyles remains Polvo’s defining characteristic, mixing distortion-driven noise with post-punk’s angular riffs. His guitar could even evoke emotions that no amount of singing could, as on the beautiful, melancholy “My Kimono”. Few bands were as daring as Polvo was in its time, and even fewer could pull it off credibly, which is why Today’s Active Lifestyles manages to resonate years later.  Kevin Korber

Kevin Korber

Superchunk

Foolish (1994)

Foolish found Superchunk in emotional tatters, reeling from a tricky ideological divorce from Matador as well as Mac McCaughan and Laura Ballance’s dissolved relationship. The album finds the band at odds with its own identity, as Superchunk’s punchy, high-energy punk slowed to a crawling pace, and McCaughan’s lyrics got more personal (and more vicious) than ever before. By all rights, Foolish should have been a disaster, but it not only works, it’s arguably the quintessential indie rock album, one that laid out a groundwork for dozens of bands who followed in its wake.

Much of the success of Foolish could easily be credited to producer Brian Paulson, who understood the band’s more adventurous side as something to expand upon rather than hold back. In his hands, the more meditative, melodic work of “Driveway to Driveway” and “Like a Fool” have room to breathe, and they become the anthems that they were destined to be. Superchunk was always a rousing, fun band on record and in person, but Foolish was the first time that it really demonstrated the kind of range it had both lyrically and musically. That it’s still a touchstone for many indie rock bands — some of whom ended up signing to Merge — is a testament to the record’s sheer brilliance.  Kevin Korber

Kevin Korber

Lambchop

I Hope You’re Sitting Down(1994)

At Merge Records’ five-year mark, the fast and noisy guitar rock that had been its backbone was still going strong, but a greater diversity was emerging with newcomers like the Magnetic Fields and Lambchop — both of which would release unusual “country” albums with their 1994 Merge debuts. A Nashville-based collective with upwards of a dozen members, Lambchop might be the most difficult-to-classify act Merge has had, a group where country, soul, jazz, rock, and experimental tendencies coalesce into lush orchestrations, accompanied by frontman Kurt Wagner’s gentle speak/sing and always colorful storytelling. Later Lambchop albums — notably, 2000’s Nixon — may have finetuned the group’s sound, but 1994’s I Hope You’re Sitting Down (alternately titled Jack’s Tulips) provides Lambchop’s most satisfying mix of stellar songs, sweeping soundscapes, and surprising turns. From the elegant downer of “Soaky in the Pooper” to the career high point of “Let’s Go Bowling”, the album expertly matches the group’s musical sophistication with Wagner’s front-porch wisdom, off-hand observations, and occasional dirty jokes.  Mike Noren

Mike Noren

East River Pipe

Poor Fricky (1995)

Truly, any of East River Pipe’s seven albums could be featured here, as they are nearly equal in how well they present F.M. Cornog’s uniquely observant and affecting songwriting. Poor Fricky doesn’t stand head and shoulders above the others, but it does feel like one of the most cohesive, efficient encapsulations of that particular melancholic beauty that is East River Pipe. It’s also essentially a proper debut album, the first he recorded as an album. Nineteen years later, Poor Fricky has in no ways aged or become dated, which says something about how separate from fashions and trends this music was all along. It speaks to the timelessness of the almost otherworldly bittersweet dream haze that the album floats through, even as Cornog is consistently cutting to the quick; atmospheric music that also punches you in the gut. Occasionally Cornog stumbles onto a proper bubblegum hook, like on “Here We Go”. More often the pleasure is in the melodic way he drifts and ruminates. He sometimes almost meditates over the home-recorded synths and drum-machine beats, as on “Keep All Your Windows Tight Tonight”. Mostly he’s creating his own little pop universe, A.M. radio hits for outcasts, about alienation and healing and walking the dog alone at night.  Dave Heaton

Dave Heaton

Butterglory

Are You Building a Temple in Heaven? (1996)

Looking in the rearview back to indie rock’s golden age, Butterglory’s Are You Building a Temple in Heaven? was more a product of its times than a shaper of its era, unlike a number of the entries on this list. But back in the day, the Kansas-by-way-of-California boy-girl outfit captured what was happening in the post-Slanted and Enchanted mid-’90s better than any Merge band did during the label’s formative years: At the top of the call sheet for the next Pavement, Butterglory mastered — to the extent that it required mastery — the combination of bittersweet vocals, oblique lyrics, and thrift-store guitar play. Yet despite the obvious resemblances to Pavement, especially Matt Suggs’ Malkmus-like intonation, Butterglory made its own variations on familiar indie themes with a joie de vivre that never felt borrowed or second-hand. Indeed, 1996’s Are You Building a Temple in Heaven? has aged surprisingly well because of its spirit, the genial good vibes between Suggs and Debby Vander Wall feeling evergreen. Better yet, the album is more fleshed-out and less tossed-off than you remember old-school indie rock being, what with the touches of horns on “The Halo Over Your Head” and “Rivers”, a glimmer of chimes on “She’s Got the Akshun!”, and synth bobbing and weaving through the whole thing to give it heft and texture. Butterglory’s albums might’ve ended up in the bargain bin of history, but they’re a good reason to sort through the cut-outs.  Arnold Pan

Arnold Pan

In the Aeroplane Over the Sea, 69 Love Songs, and more

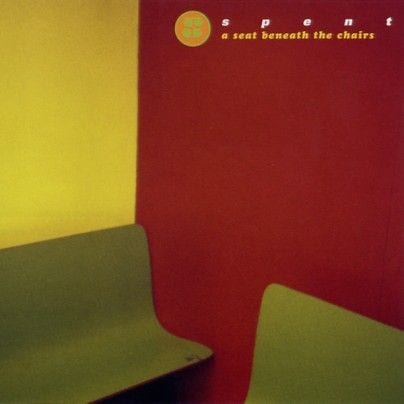

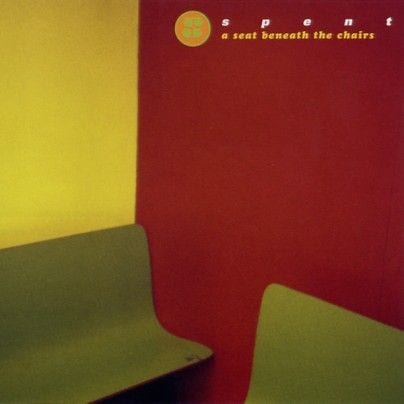

Spent

A Seat Beneath the Chairs (1997)

Jersey City’s finest, Spent is a group far too few people seem to remember. They refined and prettified their sound on their second, and final, album A Seat Beneath the Chairs. Their base sound had something quintessentially ’90s indie guitar-rock about it, but they took that sound in a different direction, with their clean, distinctive guitar style; they had my favorite guitar sound of the ’90s, in part courtesy of Annie Hayden’s melodic solos. They also boasted a multi-faceted demeanor that came from having, essentially, three lead singers with different personalities, in Hayden, John King, and Joe Weston. A Seat Beneath the Chairs played to each of their strengths while they got better at complementing each other, at singing and playing as a unit. Together they could take a light, gentle melody and then amp it up into a rebellious cry. They also could capture quiet, small moments, between people or one’s own thoughts, vividly. While songs like “Stumble Up the Stairs” are underrated, glorious sing-along anthems of the time, tracks like the glacial “Until We Have Enough” stood time still. All in all, theirs was a smart, biting, and at the same time thoughtful and sensitive approach to the rock-pop music of the day — a rare and special combination.  Dave Heaton

Dave Heaton

Neutral Milk Hotel

In the Aeroplane Over the Sea (1998)

Many of Merge’s greatest albums were documents of their time. Superchunk defined ’90s indie rock. Spoon was one of the great avatars of ’00s cool. But Neutral Milk Hotel’s gift was its ability to step out of time and bring listeners somewhere altogether foreign. Although it was released in 1998, In the Aeroplane Over the Sea is a menagerie of songs and images that seem to have been pulled randomly from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Inspired loosely by The Diary of Anne Frank, Jeff Mangum’s magnum opus is a beautiful tangled mess of sex, death, love, innocence, loss, and, ultimately, triumph. These emotions are channeled through singing saws, trumpets, banjos, and one very fuzzed-out acoustic guitar that sound like they belong in a long-lost carnival sideshow.

Not everyone gets In the Aeroplane Over the Sea, but those who do tend to connect with it on a level best described as “spiritual”. From the warm double-tracked strum and the opening phrase “When we were young” on “King of Carrot Flowers, Pt. 1” to the pronouncement near the end of “Two Headed Boy, Pt. 2” that “God is a place you will wait for the rest of your life,” the whole thing feels like a mystical fever dream sung by a child trying to be an adult…or vice-versa. That naked honesty resonated loudly, as the album has become a shibboleth in many corners of the indie world, as songs like “Two Headed Boy”, “Holland, 1945”, and title track have moved quickly from fan favorites to scripture. Getting In the Aeroplane Over the Sea down on tape was like catching lighting in a bottle and it quickly became something larger than simply a record. It’s moments such as these that great labels help usher into the world.  John M. Tryneski

John M. Tryneski

The Ladybug Transistor

The Albemarle Sound (1999)

The Ladybug Transistor is another band that has quietly built an impressive discography on Merge, but The Albemarle Sound may be their finest, most defining statement. Band leader Gary Olsen assembled his band for this 1999 gem and whipped up a tightly constructed but loose feeling record of blessed-out ’60s-influenced pop. It’s an album that drifts intoxicated through various fields of sound like the sunburst shine of “Six Times”, the string-laden romantic sway of “Today Knows”, the front-porch thump of “Oceans in the Hall”, and the intricate, ever-shifting “Aleida’s Theme”. The album manages to seem hazy while still feeling coated in very real stuff. Not dust, though. The lush spaces of the cover art, all that greenery, seem to give off the spores that coat these songs. They are tunes that blossom and bloom outward, outgrowing the humble compositional pots they start in. In the end, every song ends bigger than it began, while at the center of it all, Olsen beguiles with the subtle range and charm of his crooning. Fifteen years on, the album still feels fresh. There were a lot of bands with albums exploring a similar time in pop’s past in 1999, but oddly enough too many of them sound dated now. The Albemarle Sound, however, continues to ring out true as ever.  Matthew Fiander

Matthew Fiander

The Rock*A*Teens

Golden Time (1999)

The recent double-vinyl reissue of 2000’s Sweet Bird of Youth brought the Rock*A*Teens some long overdue acclaim, but for many years the group’s string of outstanding Merge releases seemed to never get the credit they deserved. Hailing from Cabbagetown, Georgia, the Rock*A*Teens created burly, beer-soaked rock anthems with a dark Southern twist, an approach they perfected on 1999’s Golden Time. Frontman Chris Lopez’s vocals are overpowering yet vulnerable, drawing every bit of desperation out of oddball lines like “Freedom Puff, don’t you realize what you’re a part of?” Lyrically, what the group might have lacked in crystal-clear storytelling they made up for with colorful imagery and the detailed depiction of everyday people, places, and conversations (“Clarissa, Just Do It Anyway”). The group’s ramshackle recording approach might be described as lo-fi, but the songs always found a way to rise above their basement-level production, with sturdy choruses seemingly echoing out across vast open spaces. Some early lines on album highlight “Across the Piedmont” describe a child who finds a tattered object in a field and hides it away in the weeds where only he can see it — an apt metaphor for a band that might’ve been Merge Records’ best-kept secret.  Mike Noren

Mike Noren

The Magnetic Fields

69 Love Songs (1999)

Ironically enough, the Magnetic Fields’ 69 Love Songs was such a big production that only a smaller, more flexible, and more creative indie label like Merge could’ve rolled the dice on it. With its triple-disc boxset format and suggestive title — completely literal and totally playful at the same time — it wasn’t likely that a risk-averse, bottom-line minded major label would have put out 69 Love Songs, despite the growing buzz around the Magnetic Fields and mainman Stephin Merritt at the time. But with the benefit of hindsight, 69 Love Songs should’ve seemed like the slam dunk it turned out to be, with one of the great songwriters of this era reaching the height of his strange powers, putting the Great American Songbook to use in ways no one imagined before — or since. Tapping into songwriting traditions without being beholden and intimidated by them, Merritt explored love in all its messy, confusing, anxious, and euphoric ways, deploying four singers to deliver his flowery language, biting turns-of-phrase, and ingeniously weird analogies. With all the pomp and circumstance around the set, it’s easy to forget that, musically speaking, 69 Love Songs was a big leap ahead for Merritt and company, as they moved away from the lush, synth-heavy arrangements of the early Magnetic Fields recordings into something more organically composed, often weaving together cello, banjo, and piano in intricate ways. The gamble obviously paid off for Merritt, who rightfully has his entry in the pop music pantheon, and for Merge, which emerged from its status as a purveyor of indie cred into the trailblazer it would become in the millennium to come.  Arnold Pan

Arnold Pan

Funeral, Transfiguration of Vincent, and more

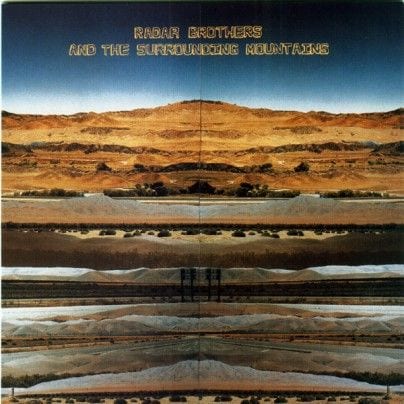

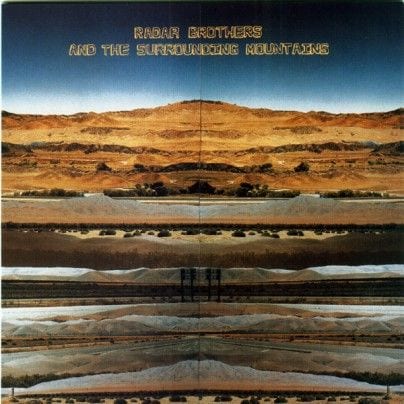

Radar Brothers

And the Surrounding Mountains (2002)

We all too often talk about innovation and consistency as if they are totally separate. But bands like Radar Bros. remind us that there is an area of inclusion where those two circles meet. What makes Jim Putnam and company innovative is the way they make grand soundscapes out of the most basic elements, and nowhere in the band’s, yes, absolutely consistent catalog is this clearer than on And the Surrounding Mountains. The electric fills bleeding out over a warm acoustic strum on “You and the Father”, the cool piano chords rippling through “Sisters”, dripping fills and layered vocals on “Camplight” — these songs and so many others stack layers of traditional rock instruments to create spacey pop songs. The songs on this record are as muscular as they are atmospheric, as quietly blissful as they can be melancholy. What ties it all together, the atmosphere and sweet melodies, is the melting yet sturdy bass work of Senon Williams, weighing these songs down so they float without drifting off. This combination of layering and immediacy, of atmosphere and clarity, makes And the Surrounding Mountains one of the great unsung pop records from one of the great unsung bands. Arcade Fire may get a lot of attention, but the quiet, ongoing craftsmanship of the Radar Bros.’ sound makes them a truly quintessential Merge band. And the Surrounding Mountains, then, isn’t their greatest album, it’s their first of many great albums.  Matthew Fiander

Matthew Fiander

The Clean

Anthology (2003)

Merge has long been one of the biggest Stateside boosters of New Zealand underground-pop, with the label’s connections running deep by putting out releases from prominent Kiwi acts like the 3Ds, the Cakekitchen, and the Bats. But it’s the imprint’s association with the Clean and David Kilgour that has been the most enduring and fruitful, with their post-2000 output coming out on Merge. Nothing has symbolized this mutually beneficial relationship better than the Clean’s Anthology: Although it doesn’t include any original material, the stuffed-to-the-gills two-disc collection is the most pivotal NZ release on Merge because it gave greater exposure — finally — to the Clean’s seminal early material, which, during the CD era, remained oddly and obstinately hard to find in the U.S. despite the group being a name brand in indie circles. Anthology served an important dual purpose, providing an overview of the Clean’s prolific first decade-and-a-half at the same time it was deep dive into hard-to-find out-of-print recordings that, for many, made ’em a prime example of a band you heard of but hadn’t really heard. The first disc, in particular, would be a horizon expanding history lesson, except that proto-indie early ’80s tracks like “Tally Ho”, “Billy Two”, and “Getting Older” sound so vital no matter when you hear ’em. And if you missed them the first time — or the second time — Merge has recently reissued Anthology, speaking to the Clean’s timelessness.  Arnold Pan

Arnold Pan

M. Ward

Transfiguration of Vincent (2003)

M. Ward’s music has become inextricably linked with a kind of nostalgia for a way music used to be made. If he’s not the only person who loves old country records, or obscure 45s, or John Fahey, he is the only one who manages to make his records feel like aged artifacts from the first note. It’s an incredible accomplishment, but on his first album for Merge, Transfiguration of Vincent, the mix of that longing for a past with personal loss and heartache proves potent. Ward later released Transistor Radio, which calls to your attention its genre-hopping, but Transfiguration of Vincent moves even more deftly from tradition to tradition. The dusty power-pop of “Vincent O’Brien” links to the buzzing folk of “Outta My Head”, while “Involuntary” and “Undertaker” offer a swaying, melancholic counterpoint. We get hints of everyone from Fahey (the album title is an allusion to his work) to Django Reinhardt to all manner of folk and blues traditions. The songs themselves are down-and-out stories of loss and lost love, of loners wondering how they ended up so lonely. But if the words are about being trapped, the music is playfully free, and Ward twists tradition as much as he honors it. One needs only to hear his heartbreaking version of David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” to see that Ward hears music in his own way, and finds his own unique voice within all of these traditions on Transfiguration of Vincent. It’s an album that doesn’t come up as much as others when we talk about Merge classics, but that doesn’t mean we can’t (and shouldn’t) change that tune.  Matthew Fiander

Matthew Fiander

Arcade Fire

Funeral (2004)

Funeral is a landmark album, both for Canadian music and for Merge Records. After receiving glowing reviews upon its release, the LP quickly sold out of its initial pressing, and has since been certified Gold in the United States. One can only imagine that the “Arcade Fire money” has allowed Merge to grow and put out more quality acts. And while some Canadians might be now sick of the album from radio overplay, it still has the power to captivate, and this is arguably the band’s finest moment. Ranked at No. 151 in the updated version of Rolling Stone‘s 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, Funeral, despite its title and the fact that it was inspired by the deaths of family members close to the band, is a joyous and celebratory affair. Not one track is a throwaway, the album works as a unified whole, and it’s no surprise that Funeral yielded no less than five singles, or half the album. And while Arcade Fire’s output since has been consistent, but not quite as rewarding, Funeral is important because it turned international attention towards the Montreal music scene and Canadian music in general. For that reason, Funeral is probably the most crucial release, outside of perhaps Superchunk’s, put out by the label, and is a reminder of just how great music can be, no matter the country of origin.  Zachary Houle

Zachary Houle

Teenage Fanclub

Man-Made (2005)

Teenage Fanclub could have easily disappeared into the ether. A prominent band in the ’90s that grabbed headlining spots at festivals in the UK, American audiences never warmed to them as they should have. Their spot on Merge Records seems perfect in hindsight, as they’re cut from the same cloth as Superchunk, the Ladybug Transistor, and the Magnetic Fields, albeit with a bit more polish and shine to their sound. Man-Made, their debut for Merge, is flawless. Twelve tracks of harmonized power pop and readymade singles from a band that has more songwriting talent than all of the biggest names in indie pop. Man-Made breezes through the darkness and the light with simple elegance. “Cells” turns a sour subject (“cells breaking down” into nothingness) into a hummable run the Flaming Lips only wish they could write. “It’s All in My Mind” and “Nowhere” could be lost Big Star tracks, and “Feel” wraps up all the sounds of a brilliant summer day with a psychedelic ribbon. Get in and get out could be the band’s mantra.  Scott Elingburg

Scott Elingburg

Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga, Destroyer’s Rubies, and more

The Rosebuds

Birds Make Good Neighbors (2005)

Wearing your heart on your sleeve is dangerous business in the age of irony. But the Rosebuds have made a lasting career out of embracing the delicacies of romance and the types of relationships it can outlast or destroy. More often, and especially on Birds Make Good Neighbors, the Rosebuds sing to celebrate the love we’ve found. “Were hearts not drawn on caveman walls?” singer/guitarist Ivan Howard asks. His solution? Rewrite history books to include the stories of lovers. The duo of Howard and Kelly Crisp (once married, now divorced) is the beating heart of the Rosebuds; their songs are simple, guitar-pop with brilliant melodies often rife with animal imagery, too. Wildcats, birds, foxes, permeate their songs, but they don’t cross the line into twee or cute pop. They’re too earnest and too hardened for that type of moniker. The love they sing about is a chiseled one, ground down to its stony essence. The Rosebuds have animal instincts in their blood and Birds Make Good Neighbors is a paean to love for the animals that we are.  Scott Elingburg

Scott Elingburg

Robert Pollard

From a Compound Eye (2006)

Guided by Voices bandleader Robert Pollard kicked off an official solo career after the initial dissolution of GbV with this double LP for Merge. While Pollard’s stint on Merge was relatively short — he only released four albums with them before striking out on his own boutique label — From a Compound Eye is important for a number of reasons. First, and this might be a controversial opinion, but this double LP is the last remotely essential release that Pollard ever recorded (his work with the newly formed GbV is dodgy at best). Second, this was the first Pollard solo album to chart on Billboard. Thirdly, the album is noteworthy because it is full of songs drawing on a backlog of unreleased material, allowing previously unheard stuff to become part of the Pollard canon. And there’s plenty of outstanding material to listen to here, which is unsurprising given that the album is 26 songs deep. My favourite is “The Right Thing” with its fake lo-fi intro, before the proper song rears its beautiful head and rocks out in a breathtaking fashion. From a Compound Eye, while having its faults (and what double album doesn’t?), is a necessary release for anyone interested in the magical wonder of Robert Pollard and his various bands, and is a solid reminder that when Pollard was on, he was on.  Zachary Houle

Zachary Houle

Destroyer

Destroyer’s Rubies (2006)

In one word, Rubies is labyrinthian. Reductionist definitions aside, Dan Bejar has been mining decades of pop/rock and modernist prose for almost 20 years and Rubies is his dissertation. (His epilogue is a thesis, 2012’s Kaputt.) How else to account for the shifting, near ten-minute opener “Rubies,” a song that, once it tires of its winding lyrical tails, resorts to a chorus of “da da da dum”s? All of this is to say nothing of Bejar’s recurring themes and characters: phony Beatlemania, the sick priest, the titular gems. Yet, for an LP of such enormous scope and breadth, it is surprisingly simple in its execution. Pop songs swing in and out of frame (“European Oils,” “Painter in Your Pocket”) alongside deeper tomes (“Watercolors into the Ocean”). All of his work culminates succinctly and quickly, too. Bejar has a lot to say, but has no time for extraneous work or ambivalence. As our attention spans grew shorter, Rubies was the last shot into the air for the literary like-minded. Pay attention now, Bejar seemed to be saying, because things are about to change in ways we can’t fathom. He was right, of course. There’s no more room for poetry in pop music and we are all guilty of its death.  Scott Elingburg

Scott Elingburg

Camera Obscura

Let’s Get Out of This Country (2006)

It was hard to fault fans and critics for the endless Belle and Sebastian comparisons heaped on Camera Obscura in the band’s early years. They were Scottish, included a male-female (or should I say female-male?) musical dynamic, and crafted beautiful bedroom pop gems, sometimes even with the help of B&S members. But after John Henderson pulled up stakes in 2005, Tracyanne Campbell took the band to Sweden to lay down the record that would leave the B&S comparisons behind. Bathed in luxurious organs and positively dripping with lovely melodies, Let’s Get Out of This Country is a wonderfully classic pop album — catchy, diverse and lovelorn.

The album is anchored by the title track and the lead single. The former, an ode to wanderlust, is suffused with both the weary heartbreak and cautious optimism that define Campbell’s appeal, not to mention a swelling score that demands a place at the front of every roadtrip playlist. The latter, “Lloyd, I’m Ready to Be Heartbroken” is a cheeky response to Lloyd Cole’s “Are You Ready to Be Heartbroken?” that is both propulsive and charming, enticing the listener to keep going. And it’s in the album tracks that Let’s Get Out of This Country truly shines: Campbell continually finds new forms in which to pour out her sorrow, be it the country lament of “Dory Previn”, the sultry slink of “Tears for Affairs”, or sad waltz of “The Great Contender”. Personal in conception, cinematic in execution, Let’s Get Out of This Country is an enchanting stroll through the many lenses we use to dull life’s inevitable heartbreak.  John M. Tryneski

John M. Tryneski

Spoon

Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga (2007)

Spoon is a band that has delivered consistently excellent albums, so it’s tough to pick just one album to represent the best that Merge has to offer from this group. However, Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga should be the go-to album for anyone interested in Spoon, as it is all killer and no filler, and boasts what is probably the outfit’s best-known song in “The Underdog”. The album’s popular appeal is such that while I was browsing for books in a Toronto chain bookstore not long after the album’s release, the record was played in its entirety over the PA system in the store. However, Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga is not just a great album for book nerds, it’s a great album period. From the Beatles-esque “Don’t Make Me a Target” to the avant-garde stylings of the haunting “The Ghost of You Lingers” to the breathless “My Little Japanese Cigarette Case”, Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga is wall to wall with terrific songs, including a cover of the Natural History’s “Don’t You Ever” (here titled “Don’t You Evah”). Here’s a bonus tip: buy the album on vinyl. There’s no runout groove on Side Two, and the album ends on a continuous loop of music. Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga is a fantastic statement, but, really, can you go wrong with any album by Spoon? The answer is no.  Zachary Houle

Zachary Houle

Wild Flag, Transcendental Youth, and more

American Music Club

The Golden Age (2008)

Merge has a knack for catching established artists as they are hitting a new peak (see: Bob Mould, Richard Buckner, David Kilgour, that Buzzcocks record you’re just now remembering), but the return of American Music Club was a revelation. The anger and ache of Love Songs for Patriots was the band’s first record in ten years and also one of their best, but it also merely set the stage for The Golden Age. The album, a weary echo of its predecessor, feels more ethereal and yet resonates much deeper. The album opens with the dreamy roll and shuffle of “All My Love” and Mark Eitzel breathing out, “I wish that we were always high.” The rest of the album approximates that haze while also churning up the worry that brings on that wish. Eitzel has always dug into the darkest corners of the room, but his trick is that it’s there he finds light. And The Golden Age has some of his brightest darkness, with career-highlight songs like “Who You Are” and “Decibels and the Little Pills”. The album tones down the dramatics and edge of early AMC records and in its place is a sound so fragile you almost miss the strong weave of its layers. Eitzel’s back on his own these days, but when American Music Club came back and found a new home in Merge, they also produced their best album in The Golden Age. This was their highest high, so every time this record spins, Eitzel gets that opening wish.  Matthew Fiander

Matthew Fiander

The Clientele

Bonfires on the Heath (2009)

Merge’s scouting reputation, their ear for talent, is a story all its own. When the news came sometime around the last turn of the century that the label would be releasing music by the UK trio the Clientele, a band some of us had already been rapturously following from import-only 7″ to 7″, I was overjoyed. Fast-forward nearly a decade beyond that, and you reach Bonfires on the Heath, the group’s final full-length album (so far). It contains all of their progress in glimmering fashion and captures the essence of their music: the unique combination of romance, surrealism, and vivid, bittersweet atmosphere. Some of the songs have the exact same intimacy and immediacy as their earliest, most home-recorded songs, while others stretch out in a manner befitting a group who has practiced new tricks and incorporated new styles into their sound over the years. It’s an album that stands in some ways as the most complete actualization of their approach to pop music. Perhaps knowing this album could be this kind of career-summarizing effort, they also revisit the earliest Clientele song, “Graven Wood”. The album concludes with a late-afternoon stroll through a park, a lovely, brief, and inconclusive moment typical of the Clientele. “I don’t know what more I can say” are the words they leave us with.  Dave Heaton

Dave Heaton

Wild Flag

Wild Flag (2011)

The recently departed Wild Flag was a kind of unicorn of the musical world — a supergroup that was actually as good in practice as it seemed on paper. Composed of Carrie Brownstein (Sleater-Kinney), Mary Timony (Autoclave, Helium), Rebecca Cole (the Minders) and Janet Weiss (Sleater-Kinney, Quasi, the Jicks), the group came together as if by fate in late 2010, releasing their sole album the next year. Wild Flag is a delirious mélange of the kind of garage, punk, psychedelia, FM jams that teenagers grok to in their cars, delivered by women with enough experience to know just how life-affirming that kind of music can be.

From the distorted jolt of keyboards that introduce “Romance” to the skronkily riffed fade-out of “Racehorse”, the songs on Wild Flag insinuate themselves with every listen. The record is suffused with the enthusiasm of youth filtered through the confidence of maturity which makes for a front-to-back tour de force. Unlike their earlier collaboration, the Spells, Brownstein and Timony seem of a same liberated mind, singing about music, movement, meaning, and connection on nearly every song on the album, which Weiss and Cole back up with taut, propulsive accompaniment. Never overstaying its welcome, Wild Flag is a supremely satisfying one-off in the Merge catalog, the kind of record that leaves you happy to be wanting more.  John M. Tryneski

John M. Tryneski

The Mountain Goats

Transcendental Youth (2012)

The Mountain Goats spent much of the last 25 years bouncing from one record label to another, so it was probably only a matter of time before they ended up on Merge. It’s fitting too, since the group’s recording output has traveled a path similar to that of the label– starting with a rough, riveting early run overloaded with jittery energy, and moving into a distinctive second phase marked by more complex songcraft and fleshed-out arrangements. On the Mountain Goats’ 2012 album Transcendental Youth, John Darnielle’s tales of wayward characters and destructive behaviors are given a variety of treatments, from sparse piano backdrops to sturdy indie pop to lively horn sections. “The Diaz Brothers” and lead single “Cry for Judas” rank among the most accessible tracks the group has produced, while “Amy aka Spent Gladiator 1” references Amy Winehouse in a memorable celebration (and word of warning) for a reckless life lived on the fringes. Striking the right balance between studio embellishment and the Mountain Goats’ trademark raw simplicity, the album stands as a late-career highlight and a promise of even better things to come.  Mike Noren

Mike Noren

Mikal Cronin

MCII (2013)

Instead of putting its cultural capital behind the blogosphere’s next big things, Merge has, of late, been giving a platform to up-and-coming artists who are gaining attention for being true craftsmen — in other words, the label is sticking with a business model that’s worked for 25 years now. In that vein, this 25th spot could go to, say, Mount Moriah’s Miracle Temple or William Tyler’s Impossible Truth, but let’s slot in Mikal Cronin’s MCII, as fine an example of how the next wave of Merge mainstays are taking well-trodden sounds and putting their own twists on them. So while he’s often chalked up as part of the garage rock revival, Cronin flashes more power-pop workmanship on 2013’s MCII than you’d expect going in, bearing as much of a resemblance to Big Star and Elliott Smith as he does to compatriots Ty Segall and Thee Oh Sees. Indeed, what stands out about MCII is how effortlessly timeless its best melodies are, whether you’re talking about the pop symphonics of the opener “Weight” or the yearning strum of “I’m Done Running from You”. Yet despite all the elements that recall the best that power-pop and garage-rock can offer, it’s hard to put your finger on exactly what Cronin’s influences are, because everything about MCII is so complete on its own terms. Giving the floor over to artists approaching their prime like Mikal Cronin is, Merge’s future is as bright as its bench is deep.  Arnold Pan

Arnold Pan