Excerpted from The Youngs: The Brothers Who Built AC/DC by Jesse Fink. Published by © St. Martin’s Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reprinted, reproduced, posted on another website or distributed by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

AC/DC

“Back in Black” (1980)

Back in Black didn’t just signal a darker, heavier sound for the decade that was to follow for AC/DC but stands even today as a signpost of when Angus and Malcolm Young came into their own as musicians. Even, it’s not a stretch to say, as men.

Malcolm was 27 years old and Angus had turned 25. They’d changed managers, had to accept artistic and spiritual relegation for their older brother George and lost their lead singer, friend, guide, muse and lyricist. There was a new bloke with a big mop of curls out front and another, altogether odder one behind the mixing desk—someone more demanding and finicky but undeniably more brilliant than anyone they’d ever encountered in the music business.

But after four weeks of recording at Compass Point, west of Nassau on the Caribbean island of New Providence, then 12 days of mixing at Electric Lady Studios in New York City they delivered not only a great album but the best song of their lives: the title track. It remains the most penetrative AC/DC song in popular culture. It’s been covered by Santana, Muse, Shakira, Foo Fighters and Living Colour (the latter brilliantly) and sampled in music by Nelly, Limp Bizkit, Eminem, Public Enemy, Beastie Boys and Boogie Down Productions. Why?

“It’s a song that is very important in the history of rock ’n’ roll and moving on in life in general,” explains former Guns N’ Roses drummer Matt Sorum. “I always look to that song as the ultimate statement in ‘never give up.’ The greatest resurrection of a band in history.”

“Their licks, those themes they came up with,” coos Jerry Greenberg. “Oh. My. God. It was absolutely unbelievable. I just thought it could be one of the biggest all-time rock records ever and it proved right.”

But not everyone was sure. Atlantic’s head of singles, Larry Yasgar, who was on the ground ordering stock for record stores, was worried Brian Johnson wasn’t going to take with fans.

“We didn’t know if the kids were going to be turned off or what was going to happen,” he says. “Well, we found out. It didn’t matter.”

“Highway to Hell and Back in Black really are the seminal albums for the band because so many things came together,” argues Tony Platt. “The culmination of things at that particular point meant that AC/DC were at their peak at the moment that they had the best set of songs. I would say that the band was at their first peak playing-wise and Mutt Lange was at his first peak production-wise. Plus the overriding factor of having had such a tragic and important death in the band, and with the emotional aspects permeating every facet of the music, there must have been just an amazing perfect storm going on.

“The songs were direct and powerful, the playing was incredibly impactful, nothing was out of place. And the enthusiasm and prowess of Brian Johnson, with his desire to prove himself, cannot be overlooked.

Even Mark Opitz, who’d had to make way for Highway to Hell engineers Mark Dearnley and Tony Platt in the crossover from Vanda & Young to Lange, agrees the Youngs pulled out something special with Back in Black.

“Back in Black’s very good,” he says. “Highway to Hell was okay. But you can see Highway to Hell was a transitional experience for them. Powerage went, ‘Okay, that’s too far to the left; now we’ve gotta swing right because the record company wants it and we’ve got to learn how to do it so we like it.’ You could see that transformation happening there. If Back in Black hadn’t worked they would have gone home. That was crucial. A huge album. The mere title. Fuck. If we’re going to do something, it’s going to be fucking good. And we’re going to do it as best we can, no matter what. And we’re going to bunker down with Mutt; he fucking understands us. And you listen to Back in Black [against] something like Def Leppard’s Hysteria—two different records, same producer—and what needed to be done on Hysteria didn’t need to be done on Back in Black, that’s for sure. Because these guys could play.”

In the no-frills clips for the title track and five others off the album filmed in one day in Breda, The Netherlands, and directed by AC/DC: Let There Be Rock directors Eric Mistler and Eric Dionysius, Malcolm Young is not much bigger than the white Gretsch Falcon he’s playing. Him? Producing that unbelievable riff? Johnson looks like he’d tear your head off in a bar fight. But that little guy? He’s the one driving all of it. And then there’s Phil Rudd, whose desiccated, heavy drumming is eclipsed by the twin guitar work of the Youngs in the AC/DC “experience” but is as much a part of the AC/DC sound as three-chord riffs and flyaway solos.

In a 1991 interview with German AC/DC fanzine Daily Dirt, reproduced in Howard Johnson’s Get Your Jumbo Jet Out of My Airport: Random Notes for AC/DC Obsessives, Rudd says: “I don’t think about making things faster but heavier. A big hit at the right point can improve the song. The trick is the same with all the instruments. Look at the old blues players. Three notes get right to your soul whereas others can play 50 million and not touch you. That’s my style. I don’t do a lot but I do it right.”

When he left the band for those Martin Guerre years in the1980s and early 1990s, the band had lost one of its limbs. The Youngs had to shaft him first, though, to realize it.

“Big fucking cement slabs,” says F-word factory Rob Riley. “One of the greatest fucking drummers that ever fucking lived. He just lays it down. He’s absolutely fucking fantastic.”

“Phil Rudd is the heart and soul of that band,” says Mike Fraser. “He’s got really interesting placement of where the cymbals go. It’s not always on the one and three or the two and four. He’ll do sort of offbeat cymbals, though not a lot of them. So it keeps the drum part powerful and driving but still interesting.”

Sorum maintains the unshowy, languid Rudd has been there so long it’s all become symbiotic.

“It’s really the way Rudd sits in the groove. It’s all moving together, although there is a push-and-pull from the other guys that makes it so in the pocket and sexy.

“Phil’s a guy that is the ultimate example of meat-and-potatoes drumming while being very musical at the same time. He’s not the ‘Hey, look at me, I’m the drummer’ type, which really is what’s so cool about Phil.”

As with “Highway to Hell,” a catchy chorus was paramount to “Back in Black,” along with the angular, spiky rhythm.

“It sort of stores up the energy then pumps it out in little spurts,” says Platt. “The orchestration, and the way that the arrangements are set, every instrument is really doing its part. Nothing’s getting in the way of anything else. So when the vocal is spitting out that rhythmic verse the guitars are just underpinning it. They’re not trying to be clever in any way. And then when it hits the chorus the riff just riiiiips through the whole thing and the riff is as good as the melody.”

Back in Black was also an album where AC/DC happily deployed the benefits of technology to augment their sound and make it fatter and bigger, with the caveat that the tricks used weren’t obvious. For Highway to Hell, says Platt, the guitars were overdubbed “quite extensively” and the album was a “little less live” than its successor.

“Back in Black is a very honest, truthful, upfront album and I think it reflects that in the sound. One of the most important things that I remember from working with the Youngs was that you can use effects but don’t let them get heard at all. So there are plenty of effects lurking in the background of the albums that I worked on but you’re not aware that they’re there. They’re tucked in behind the natural sounds and they don’t impose in the slightest.”

Johnson’s vocals, however, were true to his capability. Contrary to rumor there was no double tracking.

“There are some reverbs and some little tweaks and tricks that are sitting there that thicken the vocal out but there’s no double tracking. On choruses there are sometimes backing vocals that are singing the same note, the melody notes, the unison notes. Mutt was particularly good at getting those kind of football crowd–type choruses without it sounding like a football crowd.”

Yet most of it was recorded with outdated equipment.

“It’s somewhat ironic because the desk that was in that studio at Compass Point at that particular time was an MCI, and it is looked on today as one of the lesser of the period desks,” says Terry Manning. “But it didn’t seem to matter, did it?”

The band that arrived at Compass Point straight after AC/DC was Talking Heads. They were there to cut Remain in Light, an album containing one of the most extraordinary songs in pop- music history: “Once in a Lifetime.”

Equipment didn’t matter at all.

Mastering the Noise Pollution

Barry Diament is widely regarded as one of the godfathers of mastering. For Atlantic Records, he was one of the first sound engineers entrusted with a newfangled technology called the compact disc. For a man whose name is synonymous (at least among audiophile geeks) with some of the biggest rock albums of all time (Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction, Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti, U2’s October, Bad Company’s Bad Company) his face should be on a few black T-shirts. For AC/DC alone he’s created compact-disc masters for High Voltage, Let There Be Rock, If You Want Blood, Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap, Highway to Hell, Back in Black, For Those About to Rock and Who Made Who.

And mastering is big business. When AC/DC signed to Sony in 2002, the first announcement made by their new record company was that the entire back catalog would be digitally remastered and reissued. Those 2003 reissues have gone on to shift tens of millions of units. The same catalog was put through the mastering laundry again when it was made available on iTunes. From an audio perspective, this constant remastering of remasters of old masters can amount to a whole lot of nothing but, with fans as passionate as AC/DC’s, it’s a license to print money. In the band’s first week on iTunes in the United States in late 2012, there were 50,000 downloads of its albums (15,000 of Back in Black alone) and 700,000 single downloads.

Mastering, unlike producing, is a solo, largely thankless activity; Diament didn’t work with any members of the band on the AC/DC catalog when he was at Atlantic. His job, he says, is to look for “the sonic truth” when he masters an album—rather than “editorialize or beautify the sound”—in order to keep the original recording and the finished master to as much parity as possible. And it’s all about dynamics.

“It is the dynamics that make a record powerful sounding,” he says. “Dynamics are the differences between the loud parts and the quiet—or less loud—parts. Dynamics determine just how much ‘slam’ the listener experiences in the drums, just how much ‘weight’ there is in the attacks of the bass or in the guitar chords and just how much ‘bite’ there is in the lead guitar solo. One of my prime goals in mastering AC/DC’s albums for CD was to preserve 100 percent of the dynamics in the source tapes.”

As was protecting AC/DC’s distinctive “space” in their music. A job that began with Tony Platt in the recording studio.

“I had room mikes up,” explains Platt. “I just controlled how much of each instrument was leaking onto the other instruments’ microphones. So that when you combine them together, it’s what I call ‘acoustic glue.’ It enables the sounds to actually feel like they’re being played in the same place and at the same time, because of course they are. So it just helps to stick it all together. And that only works if you’ve got a band who is capable of playing tracks live—two guitars, bass and drums—and can get it right.”

When the tapes got to Diament, the onus was on him to retain that space rather than augment.

“Space is one of those things that can very easily be diminished, obscured or completely eradicated by too much processing, by compression of dynamics or by a less than optimal signal path in the mastering room. In addition to preserving performance dynamics, space and air are important considerations.”

That focus on preservation included some of the incidental sounds from the recording, such as the drag on Brian Johnson’s cigarette in “Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution” and Phil Rudd counting down the beat in “Back in Black.”

“When we experience a musical performance, it isn’t just the instruments in isolation that make up what we hear,” he says. “The humans playing the instruments and the space between and around the humans and their instruments are all part of the total experience. If the original recording engineer captured these, I would consider them crucial to the whole.”

Unlike some bands, AC/DC also manages to be powerful without being teeth-shatteringly loud.

“Some artists have mistakenly been led to believe that raising the level encoded on their CD—making the record itself ‘hot’— makes their recording cut through more on the radio. In fact, the opposite is true: radio compressors tend to clamp down even more on this type of record, resulting in rather wimpy sound rather than powerful sound. It would seem many record-company executives also believe people buy records because they are loud. I don’t know about this as I’ve always bought records because I like the music. Neither do I know anyone who ever said, ‘Wow, that record is loud, I’ve just got to get a copy.’

“Making the record itself loud means other aspects of the sound must be compromised. Prime among these are the dynamics—the very place where the slam and power of the recording come from. This is why so many modern masterings have no real energy. In addition, the compressed dynamics lead to a stress response in the listener. No wonder folks aren’t buying as many records as they used to. Joe and Jane Average might not be thinking about it consciously but they know their newer records just aren’t as much fun to listen to as records used to be and they don’t listen to them as many times as they’ve listened to purchases made years ago.

“In contrast, when the dynamics of the recording are preserved, the listener will have to turn up their playback volume control, especially compared to recordings mastered in the past several years. What a difference. They can turn the recordings way up without experiencing the painful quality a ‘hot’ record engenders. And they can experience the full dynamics, the full slam, weight and power of the music in ways those ‘hot’ records just can’t achieve.”

Tristin Norwell, a freelance engineer at Alberts back in the early 1990s who relocated to London to work for Neneh Cherry and Dave Stewart of Eurythmics before becoming a composer in his own right, agrees with Diament.

“The recording purist will always want to capture and reproduce the full width of dynamics of an artist’s performance,” he says. “If you go to a lyrical theater, and you are in a good one, you will hear an actor whisper when they are being coy, and when they shout they will get the message across without it being distorted.

“Recording music is the same. But the broadcast mediums are very different and therefore reproduction tricks vary depending on the message being sent. Tools such as compression, limiting and ‘loudness’ are designed to exacerbate subtlety, not retain it. They are designed for an inattentive audience who might only ever hear music when they’re shopping, so any musical message needs to be rammed down their ears at any given opportunity.

“Back in Black works because it’s a beautiful technical reproduction of a great performance and of the space in which they are doing it. With Johnson’s voice carefully balanced between the air of the room and two great-sounding electric guitars, a drummer and a bass player, all performing with genuine ‘intent,’ it becomes a god-sent ear-candy moment.

“Any less dynamic would soften the message, and any more may send a metalhead to sleep. The point is that the quiet bits are as captivating to its audience as the loud bits. This is what an engineer is talking about when he or she talks about ‘space’—dynamic space. Space that is reproduced by a technical exercise in which we, the listener, get to ‘feel’ a performer.

“Classical music is usually the best example of this for the audio junkie, as it requires massive signal-to-noise ratios for transparent reproduction, but Back in Black comes close to this for the hard- rock junkie.”

For all the audio whizzbangery of the AC/DC catalog, it hasn’t always been so sophisticated. Tony Platt recounts a story that during the production of the Bonfire box set in 1997, George Young was forced to master the AC/DC: Let There Be Rock film soundtrack from old cassettes Platt had lying about. Norwell recalls that before he moved to the UK he was asked by Alberts to archive the entire AC/DC two-inch tape collection.

“I went into Studio 2 one day and found the in-house building maintenance bloke trying to work out why a tape he’d put on the MCI tape machine wasn’t rewinding. I asked what it was, and freaked out when he told me.

“It was an original AC/DC tape. It was so old—and a notoriously bad batch of BASF—that it was dropping metal onto the heads. By the time I got there it was half a centimeter thick. The tape was ruined. Fortunately, it was probably only about two minutes of an old outtake, but I hand-wound it back on and sent it off to be rebaked.”

Rebaking is an archiving process by which the tape is restored temporarily to allow just enough time to transfer it to a new reel.

“Anyway, with a heavy heart I turned down the job. I would have spent six months transferring every recording AC/DC had made to that date. I don’t know who did it in the end. Hopefully not the mentalist bong-head from the workshop cellar.”

A Mutt That Never Tires

While Alberts might have been sloppy with their archiving, Lange left nothing to chance in The Bahamas. Back in Black was as much a career-defining album for him as it was for AC/DC. He had under his belt a bunch of City Boy, Boomtown Rats, Supercharge and Clover records, Graham Parker’s Heat Treatment and a ream of one-offs for a gaggle of nobodies. Foreigner and Def Leppard were still to come. The only album he produced between Highway to Hell and Back in Black was the self-titled debut of Broken Home, a side group of the British band Mr. Big, with Platt engineering.

It was during Back in Black that Platt saw the first clear signs of Lange’s tendency to strive for technical perfection at the expense of feel. Progressively, Lange was becoming more of a taskmaster and today Platt is happy he got to work with him on those early albums for Atlantic and not later in his career, when Lange’s requirements for an engineer didn’t necessarily fit into what the Englishman wanted to do.

But Platt insists he enjoyed working with Lange, learned more under him than he had under anyone else for a long time and owes him a debt of gratitude. They did five albums as a producer- engineer combo before Platt went off to become a producer in his own right. And he gives a valuable insight into what set Lange apart from George Young.

“I think I was fortunate to work with Mutt at that particular point in time because I think I would have found it difficult once he became a lot more of a perfectionist. Mutt is an extraordinary producer. He is absolutely totally unique. His consideration for the artist, his understanding of the construction of songs and melodies and so on is quite extraordinary.

“A lot of people will say you’re either going to get a take that feels good or a take that’s perfect and the two things don’t go together. You’re always going to have some mistakes in a take that feels good and a take that’s perfect is probably not going to feel that great. His response to that was, ‘Well, I don’t understand why.’ He thinks it should be: ‘Let’s just keep going till we get it.’

“My ethos has always been that most of the music I really like has got mistakes in it but it feels great and it doesn’t bother me too much. From Mutt’s point of view it bothers him but it probably doesn’t bother anybody else. So we would occasionally clash about whether a take was perfect enough for him and felt good enough for me. And most of the time I would try to persuade him by using my skill and expertise to repair things, to do edits. Certainly on Foreigner’s 4 that was the case; there was a lot of me editing one note or a bar into something just to make it a perfect take so that we could have the take that felt best.”

It’s a depiction that finds no argument with David Thoener and Terry Manning. Both men paint a picture of Lange as a workaholic, someone who can get by on a few hours’ sleep, gets to the studio first and is the last to leave, who doesn’t take drink or food breaks, who’s totally absorbed in the work.

“When a band hires Mutt, they are hiring a producer with a vision,” says Thoener. “It’s not easy to follow that vision to its finality. He has a reputation for making wonderful records; that takes time and patience. Any band should know that before making a commitment to Mutt.”

Says Manning: “He’s an amazing, deep thinker and a hard worker. One thing that you will hear on occasion from people who have worked with Mutt is that in some ways they can almost get tired of being pushed to perfection. But Mutt never gets tired.”

Angus and Malcolm, used to George’s expeditious approach in the studio, are on the record as having been very unhappy about that.

Yet Mark Opitz pays tribute to Lange for achieving something important.

“His job is to satisfy two things: the artist’s integrity and the commercial proposition,” he says. “And that’s a very hard thing to do; it’s a hard balance to get right.”

No one can accuse Lange of not fulfilling that brief on Back in Black, no matter how big a pain in the ass he would become. Especially when so many of its lyrics were reputedly contributed by him. Derek Shulman calls the albums Lange made for AC/DC “incredible.” Yet the enigmatic Zambian producer would ultimately pay the price for being far too good.

As it had for the Youngs many times before and would many times again in the future, it all came to a head over money.

At a minimum Mutt Lange was costing hundreds of thousands to turn up to the studio—millions when royalties were factored in.

But the money was more than worth it, according to Steve Leber of Leber-Krebs, AC/DC’s management company between 1979 and

1982.

“They could deliver on stage,” he says. “That was never a problem. AC/DC needed something else. It was always management and a producer. Once you have that team in place you never break it up. It’s like George Martin with The Beatles. Why break it up? AC/DC not only fired Mutt Lange, they later fired us after we broke them.”

Peter Mensch, the one-time tour accountant for Aerosmith who’d taken over from Michael Browning in 1979, was terminated after an August 1981 performance at the Monsters of Rock concert at Castle Donington, England, was ruined by a malfunctioning sound system. But it affected many bands that day; AC/DC’s experience wasn’t isolated.

Mensch didn’t respond to interview requests for this book and has never explained why he thought he was sacked by AC/DC. His only comments on the matter were to Mick Wall, when he said: “I was never told why I was fired. They called their lawyer, who called David Krebs, who called me.” And to Phil Sutcliffe: “I was stunned. Till then my shit didn’t smell.” Wall comes to the conclusion that Donington was to blame for the band dispensing with their manager: “Malcolm was in a vengeful mood. Somebody would have to pay; in this case, Peter Mensch.”

By most reliable accounts Mensch was a hard worker for AC/DC: an ambitious manager who was willing to move to London, hang out and be there for the band whenever he was required. He even identified Bon Scott’s body in the morgue.

“That was my first job,” he told The Sunday Times in October 2012 as part of a profile of his marriage to former British Tory MP Louise Bagshawe. “I get a phone call that Bon Scott has died and I have to come and identify the body. I say to the rest of AC/DC, ‘Couldn’t you guys go?’ And they go, ‘No, you should go, you’re the manager.’ ”

In April 2013, in a spontaneous question-and-answer session with Reddit, he gave an example of how the band tested his loyalty: “The dumbest request I’ve ever received was while managing AC/DC. I was in London. They were in Paris. Phil Rudd wanted hot water because his kettle was broken. He called at midnight to ask me to bring over hot water… wish I had told him I would charter a flight to bring him a kettle, and billed it back. Needless to say, I didn’t go.”

Mensch briefly stayed on with Leber-Krebs but eventually came to an arrangement where he left to form his own management company—Q Prime—with business partner Cliff Burnstein. Def Leppard, a former Leber-Krebs band, was their first signing—with Lange as producer. Over four albums, the union was lucrative: 1983’s Pyromania sold 10 million copies in the United States alone and 1987’s Hysteria sold 20 million worldwide.

Today Mensch is a multimillionaire and manages acts such as Metallica and Red Hot Chili Peppers. In February 2013, Billboard jointly named him and Burnstein #55 in its Power 100 list of the most powerful individuals in music. He’s come a long way from taking late-night hot-water orders from Phil Rudd.

“I credit Peter Mensch for raising AC/DC to the next level,” says Phil Carson, the man who signed them to Atlantic and who enjoyed a close relationship with the Youngs for many years until it fell away. “I absolutely consider firing both Mutt and Peter was a mistake. Mutt’s excellence as their producer was mirrored by Peter’s performance as their manager.”

Leber is still upset about the decision and confirms “money was a factor” and the band was “set up in a crazy kind of way” with George Young and Alberts, and George may have been a “factor” in the decision to can Lange.

“It was just crazy. We loved Mutt. We thought Mutt was great. Peter went on to hire Mutt to do Def Leppard and the rest is history. Mutt became a superstar producer. The two elements that broke AC/DC were not the lawyers and the accountants who’d later take over. It was the creative forces of Leber-Krebs and Mutt Lange and, most important of all, the guys delivering on stage. They’re a great group of guys. I loved every one of them. I was upset when I lost them. Look at all the groups we had: Aerosmith, Ted Nugent, AC/DC, Scorpions. No management company has that many great rock ’n’ roll groups all at once.

“I never lost faith in the band. That’s the bottom line. I thought they were the greatest band in the world and we were right. I felt they’d always be big but I just felt that they could have been bigger and stronger if they had [kept] Mutt Lange. He was part of that greatness. The band was better with Mutt Lange than without Mutt Lange.”

But though Mensch has never spoken about why he was fired by Angus and Malcolm Young, Leber’s old partner David Krebs has an idea.

“Peter had a girlfriend working for the merchandise company who I think came over to Australia to be on tour with him,” he says. “They objected. They fired him. We took the position that we didn’t understand why they were firing him. We had, like, six months left on our contract.

The man who replaced Mensch, AC/DC tour manager Ian Jeffery, says he has no recollection of any objection to Mensch’s girlfriend.

“No, not at all,” he says. “They thought Peter had stopped having their best interests at hand and was not around enough during recordings in Paris, though he and I made the trip there [from London] every Friday.”

Australia, where AC/ DC had played before Donington, hadn’t been the happiest leg of the Back in Black tour, Mensch’s choice of companion aside. Brawls broke out after two shows at the Sidney Myer Music Bowl in Melbourne, where there were nearly as many people drunk on the park lawns outside the venue as there were inside. Police were injured, emergency rooms were overrun, trains and trees were trashed, noise complaints were lodged, 100 people were arrested, and there was talk the bowl would never host a rock concert again. The band copped a big spray in the Australian press, prompting Brian Johnson to hit back at the critics: “We were warned, we were warned. But even I thought it went over the top.”

The Dead Fish Punch of Angus Young

It was a period of enormous angst, avarice, spite, bitterness and recrimination but with little point to any of it. Not to mention physical violence. The Youngs have never been shy of a barney, from George headbutting a Cairns good ol’ boy in the 1960s (which opens Murray Engleheart’s biography), Angus punching Mark Evans or Malcolm decking Phil Rudd. Angus and Malcolm fought over Malcolm’s alcohol problem that saw him leave the band temporarily in the late 1980s. The three brothers even had an all-in punch-up over the disastrous show at Reading in 1976.

When I ask Evans why he didn’t thump Angus back, there is a long pause.

“I don’t know, to be honest,” he says and starts laughing. He concedes, though, he was drunk, out of line and out of order. The fracas had been sparked by a comment he made to Fifa Riccobono. “I held nothing against Angus for doing that because I brought it on myself. Malcolm put himself in the middle of it, along with Michael Browning, who physically had hold of me. Angus was behind Malcolm. I remember seeing a line through him and thinking, ‘I can sneak one through you.’ What stopped me, right at that very moment? I know it was respect for Malcolm, unquestionably.”

So how does Angus punch? Evans flops one of his hands onto my shoulder like a dead fish.

“Nothing. Because the guy’s tiny. He can’t hurt you. There’s nothing going on.”

Steve Leber believes Malcolm, a hothead at the best of times, was jealous of the star Angus had become and that jealousy was taken out on the band’s management company. In the Wall biography Ian Jeffery says the two namesakes of Leber-Krebs never got close to either Malcolm or Angus and Leber admits to me that “they didn’t like David . . . the reality was that David had a falling out with the band and I came right into it really soon after Peter had left.”

Krebs puts his hand up.

“I didn’t have any real chemistry with Malcolm,” he says. “I was personally handling Aerosmith and Ted Nugent, who were both major bands at that time, and in retrospect I should have handed AC/DC over to Steve, who loved them, but I split my time and took them on and it was an error. They were recording [For Those About to Rock] in Paris and I would go over for a week a month, which was a mistake.”

Furthermore, when the Youngs decided to part ways with Leber-Krebs, he didn’t stand in their way and do whatever it took to keep them.

“I don’t think I tried hard enough. I didn’t have the personal relationship to swing it around. I never thought we had the leverage to hold on to them. That was my take on it. When I went over to Paris, it was semi-strained. A lot of internal politics had begun to play with the road manager [Jeffery] who wanted to become the manager and all this other stuff that went down.”

Jeffery, however, rejects that categorically.

“Absolute bollocks,” he says. “I had no intention of becoming manager.”

Krebs continues: “I was at a meeting with Peter Mensch and Ted Albert and I made a fatal error when I said to Ted Albert, ‘You know, Ted, do you think it would [really] be a good idea to give the group back half their publishing?’ That went over not well. So you never know what that may have set in motion. I didn’t quite realize all the relationships.”

Leber says, however, that in his own case the suggestion he didn’t have a relationship with the Youngs is not true. He became friends with Angus. He would go into Angus’s dressing room after shows and talk for hours while Angus painted.

“I was very close to Angus. Matter of fact I always believed that Malcolm was—they all were—jealous of the fact that Angus, without singing a note, was the lead in AC/DC. He is the lead. There is no AC/DC without Angus. Malcolm was certainly jealous of my relationship with Angus. When I say jealous, Angus used to want to stay at my house. And I don’t think Malcolm liked it.”

Jeffery tells me that Leber’s biggest mistake was “thinking because Angus had the shorts he was it all.” A similar comment was made by Jeffery to Wall, in which he charged Leber with thinking Angus was the “route into the band” and “didn’t have a clue that it was Malcolm that ran the show.”

“Exactly. Absolutely true,” concedes Leber. “Malcolm was the businessman. I said Malcolm was jealous of my relationship with Angus—maybe jealous is the wrong word, maybe he was angered by my relationship—but Malcolm called the shots. And then Angus would not stand up for me, even though Angus was the one who pursued the relationship with me.

“But I loved the whole band. I really did like Malcolm anyway, even though Malcolm didn’t think so. I did. Malcolm was the key to making decisions and basically he didn’t want to let me run the band because he thought I would favor, I guess, Angus. But that wasn’t true. I really cared about the band, period. I felt they were the best rock ’n’ roll band out there.”

He wasn’t the only one to misjudge the power of Malcolm. “Ian Jeffery’s right,” says Krebs. “When I met AC/DC I spent my time talking to Bon Scott. We didn’t realize that Malcolm was really the engine. He wasn’t a warm person. But that could be cultural.”

Leber is prepared to admit that not working on his friendship with Malcolm was his downfall: “I didn’t play it right.” So much so that he maintains if he’d done it differently and played the Young family’s “politics bullshit” properly by befriending Malcolm the same way he’d befriended Angus, “I’d still have the band.”

Over 30 years later, he’s got some clarity on what he did wrong. “You know at the time you get so close to something you sometimes don’t see it? I didn’t realize that Malcolm would be so pissed.”

So pissed that quite possibly the most important relationship AC/DC ever had over their four-decade-long career with any of their management disintegrated.

Susan Masino, who makes considerable hay out of her friendship with the band in Let There Be Rock: The Story of AC/DC, in fact endlessly rabbits on about it, deals with AC/DC’s break with Leber-Krebs in six words: “The band stopped working with Leber-Krebs.” About as much as you would expect from a writer who admits, “I planned to give them a copy of my new book as soon as it was done. I wanted to make sure they didn’t have any problems with it.”

“Malcolm never said a word. He didn’t have to. He just fired me,” laughs Leber, but it’s a laugh rooted in some sadness. “Look, let’s face it: [Leber-Krebs] broke the band. We broke them wide open. I’m the one that got them to the number-one position in the United States. We broke Back in Black. We created the excitement for this band. We did a great job managing them. The issue, if there was any issue that was critical, was that we were outspoken. We managed bands. We didn’t let the bands manage us and we delivered.”

The Youngs’ notorious nose for a deal would claim another casualty.

“[The thing AC/DC didn’t] realize was that we were getting a decent commission but we paid for our expenses when the band wasn’t touring,” continues Leber. “So if the band didn’t tour for two years we still had the expense of running the operation and keeping the excitement going.

“We had huge expenses but the band bought into the idea that Ian could do it for three or five percent or whatever. It was ridiculous. I break the band, we do an incredible job, we get them to become a stadium band—stadiums—and we get terminated because they want to reduce our commission to nothing. Well and truly, no one took them beyond where we took them.”

So if Jeffery was getting five percent or less, how much was Leber-Krebs’s commission?

“A lot more. Let’s put it that way. I don’t think it should be in books. A lot more.”

I put a ballpark figure of 15 to 20 percent to him. Pretty standard management fees.

“Yeah, standard ballpark, between 15 and 20, but the bottom line is we were reduced to something more reasonable [to AC/DC], but we couldn’t work for five percent. I turned down many groups for that five percent bullshit. I said, ‘My time’s too valuable.’ ”

For his part, Jeffery says any suggestion he worked for “three or five percent,” as Leber alleges, is “absolute rubbish.” He too would get boned and the band would end up being managed by Alvin Handwerker, Leber’s accountant. It wasn’t so bad for Leber-Krebs, though, because according to Leber they’d done a savvy piece of housekeeping and retained a share of the AC/DC cata- log, including Back in Black, “which paid us handsomely and still does . . . not a bad thing.”

Is this a source of resentment for the band?

“Yep. They have resentment because we own the catalog. Yeah, yeah. Definitely resentment. All of our bands resent the fact we were smart managers and kept the positions in the catalog.”

So what’s his cut?

“Can’t say but it was a good situation. But life goes on. I was angry about them leaving me. We did a great job. I was pissed but hey, listen, those things happen. We didn’t get the proper recognition for breaking them when everybody else turned their back on them. I always felt that the band kind of, like, didn’t appreciate the job we did. It happens a lot. But there’s only one time in the history of a band when they really need you—and that’s in the beginning.”

So what hurt more? Losing AC/DC or Aerosmith?

“They both hurt. But there’s a difference. With Aerosmith, I ripped up their contract because they were heroin addicts and I didn’t want to kill them. And they kept on getting more and more money from me but [Steven Tyler and Joe Perry] couldn’t get off heroin, Steven especially. I didn’t want to see him die. And John Belushi had just died—before that they were friendly—and I realized that Steven was going downhill. I had sent him to many, many institutions. I wasn’t going to stay away from three kids and I wasn’t going to spend all my time with him. He needed someone who could—and would. So even though Aerosmith owed me five more albums and they had just signed a long-term contract with us I threw them out and ripped it up.”

Krebs backs this account.

“We really threw them out. They didn’t fire us. They had gone too far. I had spent over five years trying to cure them, ineptly.”

“Steven later hugged me and appreciated the fact that I’d saved his life,” reveals Leber. “Because of course, again, they don’t like to admit those things. So that one, Aerosmith, I canned them. AC/DC: they canned me—for no real reason—and that pissed me off. If they’d canned me because I was doing a bad job, I could accept that. But don’t fire the guy who broke you and did a great job over money.

“I’m not bitter about it at all. I laugh about it all the way to the bank because I kept the Aerosmith catalog and publishing. I kept the AC/DC catalog. After all these years, I still have it. More than 30 years later I still get money every year and it’s a lot of money. But at the same time I love the guys. I would have liked to have kept the relationship.”

For tens of millions of reasons.

Says Krebs, matter of factly: “Back in Black has outsold the highest selling Aerosmith album two to one.”

* * *

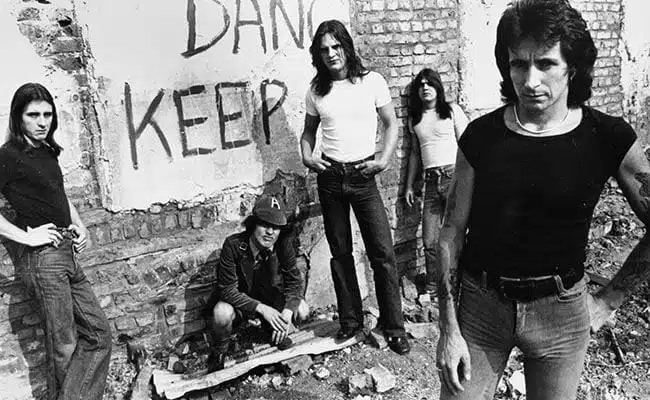

Above: Press photo from ACDC.com