Klinger: I can’t remember where I parked my car, but I think I’ll always remember the first time I saw Prince on MTV. It was the “Little Red Corvette” video, and I was watching it on a black and white portable TV in my room. (I want to say I was drawn in by all the glimpses of scantily clad ladies, but now I’m thinking that was the “1999” video. Also I have no idea how my dad got a portable black and white TV hooked up to cable.) I would have been about 14, I guess, and I immediately realized that this guy was a rock star, and he was what was going to be next. I didn’t exactly get on board as a fan — in fact, I was probably a little alarmed by what I perceived as a non-white, not-conventionally-masculine threat to the rock hegemony — but when Prince pulled off that astonishing dance move about halfway through the video, I knew that things were about to change.

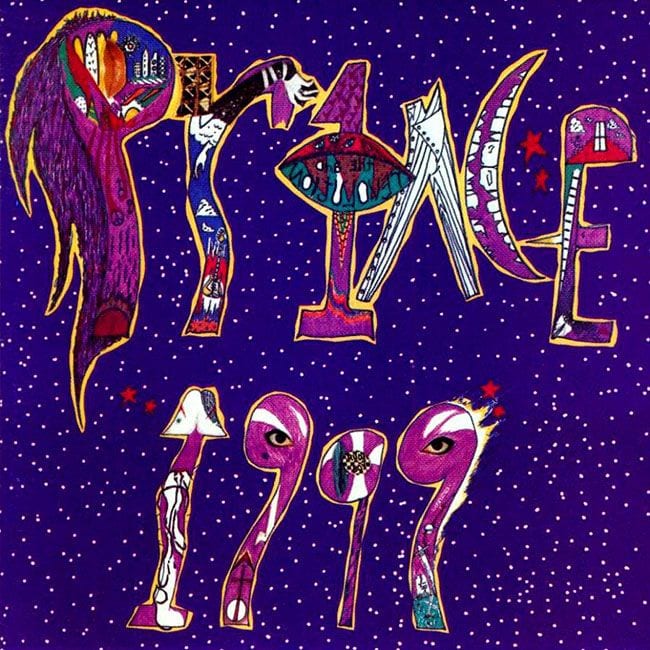

I can’t recall the last time I settled in to listen to 1999, but hearing it again after all these years is an eye-opening experience. Before Purple Rain brought him mainstream success, before the Unpronounceable Symbol made him (let’s face it) a punchline, Prince made this fully-formed statement of purpose. Comparing 1999 to Prince’s next double-LP set, I’m struck by the cohesiveness of the sound here. Prince isn’t leaping from style to style in an effort to demonstrate his range; instead, he seems to be laying the groundwork for his entire sonic framework, and we’d be hearing elements of the songs here throughout his career, from the slinky funk of “D.M.S.R.” to the sumptuously anthemic piano balladry of “Free”. Sign o’ the Times is clearly the critics’ pick (No. 30 on the Great List), and Purple Rain (No. 44) is the popular favorite, but I’m giving it up for 1999 (No. 199, appropriately enough). How about you, Mendelsohn?

Mendelsohn: Purple Rain will always be my go-to Prince album. Sign o’ the Times has its moments, as does 1999, but if I’m going to get down with His Purpleness, I’m going with the abridged version. Sometimes there is such a thing as too much Prince — and that is hard for me to say because the more I listen to 1999, the more I like it. On the flip side, the more I listen to 1999, the more I see how much growth there was between Prince’s records and just how far Prince had to go.

1999 is a great record but, as you noted, Prince was still laying the groundwork for his later albums. I wouldn’t necessarily call 1999 cohesive, I’m of the opinion that the album suffers from a sameness of sound. Maybe that was the intent, but I get the feeling that Prince was letting his music be dominated by the synthesizer. As his career progressed he started to figure out how to make the synths work within his songwriting. It is like he has a bunch of brand new toys but he doesn’t really know how to use them, so he leaves everything on the default settings. He is a virtuoso, so it still sounds far and away better than anything everyone else was doing, but by the time he got to Purple Rain, and later Sign o’ the Times, he made mastered the synth application, bending it to his will like he does with a guitar.

Klinger: Cohesiveness, sameness of sound, potato, potahto. And I’m not too up on the history of synthesizers, but I’m willing to bet that those weren’t the default settings until Prince came along. His influence on ’80s music was pretty much incalculable, up to and including that synth sound. Now I certainly understand your preference for Prince’s more concise works — I’ve noticed a few points on 1999 where I’m a little surprised that a song has gone on as long as it has (surprised but not annoyed, which is odd for me), but I think he needed the extra time to explore all the nuttiness that made him who he was. He’s written a bunch of hit singles, knowing he can cut them down for airplay, then riffs on them for a while the ensure maximum nuttiness.

Those back halves of the songs are completely bonkers, Mendelsohn, and in the best way possible. Take “Let’s Pretend We’re Married”. One second he’s alerting his intended (Marsha? Possibly a Martian?) that he would like to perform coitus upon her until she no longer has the capacity for taste, the next second he’s telling us that God is the only way. Also he’s very concerned about the bomb. On paper, his, shall we say, non-linear narrative structure might read like the manifesto of a lunatic, but he delivers everything with so much conviction and so much charisma and humor that you can’t help but go along for the ride. And then that “All the hippies sing together” line. This is a pretty funny record — I had kind of forgotten about that. I’ll refer you to “International Lover” for more proof.

Mendelsohn: You want to talk bonkers? How about “Lady Cab Driver?” That song is three minutes of the smoothest, grooviest funk followed by two minutes of what I can only assume is Prince’s list of things he would like to nail to the wall, if you know what I mean — like a funky Martin Luther with a whip, leather pants, and video camera. And once Prince finishes his manifesto, we return to the regularly scheduled funk for another couple minutes of an extended jam filled with seagulls and chiming clocks, battling synth and guitar riffs, and whatever else they found in the sampler banks. The greatest part about all of it? It works.

Klinger: It does. Although if Prince thinks he has a love-hate relationship with the Internet now, imagine what would have happened if this depiction of, erm, aggressive sexing had been released in the age of Twitter. I’ll leave the feminist response to Prince to the experts — in fact I may spend a good part of the weekend seeking that out, but it’s not difficult to see elements of his approach that could be construed as problematic.

Mendelsohn: Honestly, I’m just nitpicking. There isn’t anything wrong with 1999 except that it isn’t Purple Rain or Sign o’ the Times. It is an unfair comparison but I’m allowed to make because it’s done with the advantage of hindsight. The Prince that made 1999 wasn’t ready to make Purple Rain. He was still too young, had too many ideas, and was having far too much fun to be serious about the construction of an album. The result was 1999, a sexy, angry, goofy record that shows a young artist coming to terms with the music he wants to make but not quite succeeding at getting it all under control. If I wasn’t so damn impressed by the range (and thrust — wink wink) of Purple Rain, I too might pick this record as Prince’s true coup d’état in his bid to rule the realm of popular music. The problem is, 1999, despite all the sleaze and innuendo, lacks the swagger of Prince’s later work. He is far too earnest and open; it’s refreshing and funny but his honesty has to come second to his drive to dominate. He found the drive to dominate with Purple Rain and then solidified his artistic bona fides with Sign o’ the Times.

On its own, 1999 is a stellar record. In the pantheon of Prince’s works, it will always be overshadowed.

Klinger: You may be right, but I still maintain that that’s a shame. Because it seems to me that 1999 is the Rosetta Stone to understanding Prince, both in terms of the music and in its ability to get big picture with all the complexities of his psyche. 1999 took the political Prince of Controversy and the bawdy Prince of Dirty Mind, melded them into one, and set the stage for everything that was to come. And either way, this Prince, the guy who first appeared like a lightning bolt on MTV in 1982 with what seemed like a completely fresh sound (and minimal baggage), will always be what I’m talking about when I’m talking about Prince.