Catch up with Part One of “Worldbuilder”.

It’s always good to come prepared so I ask Paul Duffield about Lord of the Rings. Well really, about The Hobbit.

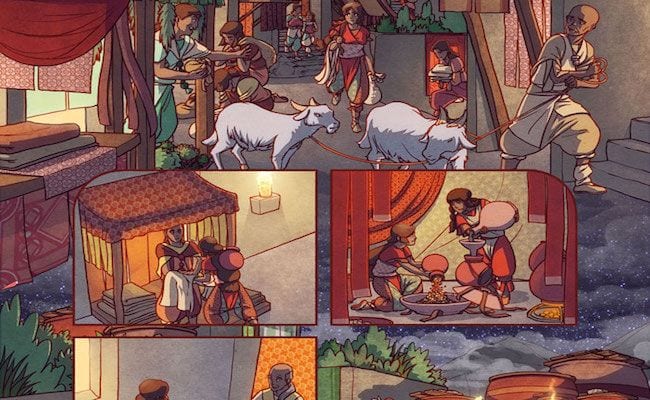

It’s meant as no slight. Duffield’s newest creative project, The Firelight Isle follows on after the rockstar levels of attention garnered by the landmark webcomic, and Duffield’s break out appearance as artist, Freakangels. This project is entirely Duffield at the helm, project creator in role of both writer and artist. The Firelight Isle puts an amazing high concept on the table — that the sequential art storytelling can be sequenced vertically rather than the traditional horizontal series of images we’ve come to expect in comics. And with that, simple, elegant insight, Duffield returns us to the power of classic storytelling (classic, at least for the comics medium). Duffield takes us back to the power of Frank Miller’s Daredevils, where the vertical sunless, steel-and-glass canyons of Manhattan, were always repurposed as horizontal spaces. Where worms-eyes and birds-eyes would open moments of Daredevil and Bullseye locked in a moment, falling through space. Where up easily, instantaneously autocorrected to down.

The power in Duffield’s Firelight Isle lies in the games Duffield himself is able to play with spatiality. The story’s intriguing, but the story’s also transitory. It can be told in a number of different ways. Games with spatiality, chapters told as a vertical “ribbon,” simply underline the power of the story itself. So it’s not a slight, and it’s not a backhanded compliment when compare Duffield’s Firelight Isle to The Hobbit. Long after the success of Lord of the Rings and well into his twilight years Tolkien himself was working on retelling The Hobbit. The original 1937 publication of the book succeeded as a children’s novel. But some 30 years or more on, with the complete Lord of the Rings trilogy behind him, Tolkien himself began to ponder, then began to work on, a retelling of the events of The Hobbit as an adult version.

Just like Tolkien, relying on his professorial expertise in philology, was poised to reanimate the original story of The Hobbit with a retelling for a more adult audience, Duffield’s Firelight Isle is animated by it’s mode of telling. Its high concept lies in its execution. This is a webcomic that works primarily for the web. It’s best read in a browser or on a handheld device. And it’s not simply a traditional comicbook, subject to digital distribution. In this sense, there’s a great overlap between Tolkien’s body of work and Duffield’s most recent creative venture, an overlap that’s far greater than the two projects simply sharing a high fantasy setting.

It always helps to come prepared, so I put the question to Duffield. I point out the similarities and ask him about any connection between his process and Tolkien’s. And because Paul Duffield is genuinely humble, and because he’s a genuinely accessible human being, he defers.

“That’s a very flattering comparison!” he enthuses. If we’d been texting this interview, there’d be a smiley-face emoji. He continues to describe an actual influence — Ursula K. Le Guin short story. Duffield continues, “If I had to cite a primary influence, it would be a short story by Ursula Le Guin called “Solitude.” Never had I been so thoroughly confronted with not just a foreign culture, but an utterly foreign way of thinking that the story provided a window into. I though that if I managed to achieve that kind of window into a totally alien frame of mind, then I’d be happy with what I’d achieved!”

And there it is.

I almost miss it as it goes by, but that’s the nature of the thing when it comes to interviews. On the one hand it’s shared energy. On the other, the person you’re speaking with will always have a unique map of the world, one they hold internally, one that motivates and elucidates their creative work. An interior map of the arrangement of concepts in the world, one that sheds a unique light. Miss that map, miss its traces in the responses you get, and the creator’s unique point of view on the world might get missed.

But there it is. The littlest gateway to Paul Duffield’s inner map, in an almost throwaway line. Duffield talks about an “alien frame of mind,” about an “utterly foreign way of thinking.” I need to push this line, but I don’t interject. I don’t disrupt. Duffield’s art disrupts the status quo, and he continues to speak.

He says, “Previously, the longest story I’d written myself was 40 pages, and FI is over 300 pages all told (actually might be closer to 400 in the new revision). So much of the time since the end of Freakangels has been spent on not just writing it, but learning how to write and manage a project of that length.”

And almost immediately, he falls into talking about the design experience culled from working on a project as large as Freakangels. He continues, “I think my experience of working to such a tight and constant schedule, and managing large workloads has definitely helped, although it’s been harder by magnitudes to manage my time on The Firelight Isle. I also learnt a lot of lessons about sustained storytelling through working on Warren’s scripts. One decision I made that went in opposition to the way Freakangels worked though was to have the story completely written before I began.”

“Warren,” of course is Warren Ellis, Duffield’s collaborator, and the writer on Freakangels. With over 40 graphic novels, Ellis is one of the most prolific, and generally considered to be a purveyor of the finest quality, graphic novelists on the planet. It was at his behest that Duffield was originally chosen as the artist for Freakangels.

Before we loop back to that insight into Duffield’s inner map, before I allow myself to, I attempt to move some of the necessities off the table. Webcomics, in the nascency it currently finds itself today, is still mired in needing to talk about its business model. Even with the mass exodus traditional comics made to digital, the business model underpinning it seemed to expand from certainty to more certainty. So I ask about business model, I ask about funding. Duffield politely answers, and I manage to take care of some necessary bookkeeping for this interview.

I expect the answer to come as banal, bland, functional. Instead, Duffield leads me to a treasure trove, both of personal insight, and of commercial reality. He begins by talking about his personal work process but quickly falls in to a discussion around the business of The Firelight Isle. “Well, right now I’m being a little lax at that because I’m just at the tail end of an incredibly intense rewrite. Around 90% of the story has been affected, so I’ve had less energy than usual for promotion!

“That being said, I went all out when I started drawing the pages (naively thinking that I’d finished the plot). I launched a Patreon page to help support ongoing costs, and I produced a printed mini-preview of the story to sell online and at shows.

“Other than that it’s the usual social-media presence and grass-roots promotion that I’m alternately okay or terrible at depending on what week it is.

“I’m also working part-time as a designer for The Phoenix Comic at the moment so I can spend at least two days a week full-time on The Firelight Isle.”

I push that line and ask about the degree of overlap between the two jobs. Paul responds, “A little cross-pollination. It’s an odd situation. David Fickling Books have offered to publish The Firelight Isle, but they made me aware that they wouldn’t have the budget to provide me with a page rate before we entered into any agreements. However, I knew due to my lack of experience with long-form storytelling that I needed a shit-hot editor, and David Fickling has worked with the best (including editing “His Dark Materials”). The job with The Phoenix (which is a sister company of David Fickling Books) was a kind of substitute arrangement, allowing me to work on the book without the pressure of raising money, so I could focus on giving the story the time it needs, and benefiting as much as possible from David’s feedback.”

There’s another pause in the conversation, but this time I don’t push. Paul’s wrestling with something, is he wrestling with something? He plunges in, “I also have very handy access to the editors at The Phoenix who are also amazing. Will Fickling’s input on the latest draft was invaluable.

“In the meantime, I built their current website and online store for them, and do all the design work on each week’s comic in 3 days a week! A kind of mutually beneficial agreement!”

What about the actual design of the website? Did Duffield code this by himself, or have this coded, from scratch? “Not entirely — it evolved from a web template produced by another design house, but I overhauled the look and added the online store (I’ll add for any web designers that this is a WordPress site we’re talking about so it’s mostly just changing the CSS of plugins).”

There’s a natural break in the conversation. We have enough for the interview, and we’re done. At nearly three hours gone since the beginning of this interview, we’re done and we can both take a much needed break. But this time it’s me taking the Leap. Time for me to push Paul on getting to that inner. So I ask. Really I crassly bludgeon.

I guide Paul back to the earlier comment and ask about the expectations, his and the fans’ both, in writing high fantasy in a climate as fraught with geopolitical tensions as it currently is. I realize how unfair the question is and offer Paul an out — don’t answer and we can leave the interview where it is. It’s already sterling stuff. But Paul, because he’s a genuinely humble and genuinely accessible human being, doesn’t take it. He turns around and confronts the question head on.

There’s a pause, then he answers. “Well, I’d like very much for it to evolve its cultural influences. I absolutely love a good medieval romp, but British history has had such a profound impact on the kinds of worlds and mentalities that fantasy characters inhabit and adopt that I long for something different. Fantasy has the ability to imagine anything — it’s as malleable as science-fiction and more so because of its ability to disregard realism. I’d like it to reflect a more globally conscious mind.” And then he offers the coup de grace, “It’s all too often that people talk about what fantasy can’t depict because of the presumed monastic, patriarchal, dark-ages setting.”

I’m lost in the wonder of this. Lost in the mind at work, grappling with these issues. It’s been too long that we’ve collectively lived in the shadow of first, Lord of the Rings, Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, that’s promoted a Platonic, perfectly-realized, perfectly-visualized version of Tolkien’s work, and at its worst, left Tolkien’s trilogy bereft of its inherent nuance around race and culture. And second, too long we’ve lived in the shadow of HBO’s Game of Thrones which has left us thinking that the best kind of sociopolitical commentary high fantasy can offer is to be informed by the paranoia of spy thrillers, corporate intrigue dramas and gangster flicks like those made by Coppola or Scorsese.

Not to deride those works. They have their place. But Duffield’s inner map leads us into completely uncharted territory. Imagine using a platform like that Nickelodeon cartoon from years back now, Avatar: The Last Airbender, and launching into something that has the impact of Neuromancer. This is the promise in the kind of story Duffield draws us into with The Firelight Isle.

But Duffield goes even further. He describes how he built the political reality of The Firelight Isle. “One of the boundary states that I set for The Firelight Isle (quite literally) was that the culture depicted has developed on a small island, providing a limit to growth,” Duffield continues, “Not Easter Island small, but not quite British isles big either. It’s a culture millennia old, so it’s had the chance to grow and experience conflict, and the state we see it in at the beginning of the story is a sort of temporary equilibrium.

“The system of rule that they experience is both deeply religious and highly structured — essentially investing all martial power into a single group who act as priests, police, and a number of less easy to define roles.

“Although no one on the island would describe it that way! It’s easy to enter ‘intellectual analysis mode’ when thinking of a culture, but I set about creating one as seen from the ground up, through the mind of someone raised in it, and with the nuances and differences of thought that entails.”