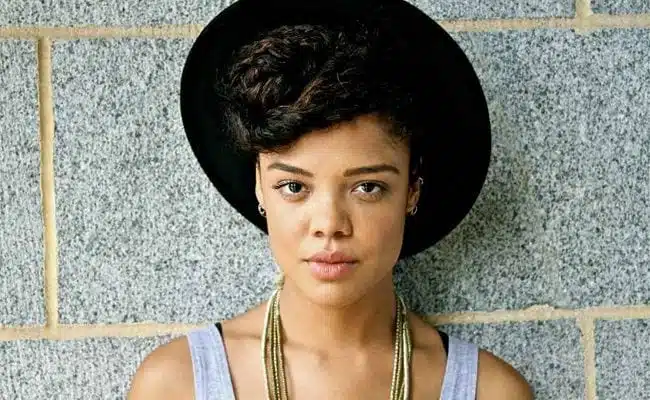

Dear White People maintains a delicate balance between its relentless upending and exposure of the racism that courses throughout our daily lives and tracing the ways in which race and racism entangle with our sexual desires, in the process complicating any notion of a singular identity. The film revolves around an incident where a white-run campus humor magazine, Pastiche, holds a blackface party. Even before the party commences, a racist invite circulates that channels centuries’ worth of anti-black racial stereotypes under the guise of tongue-and-cheek humor. Sam (Tess Thompson), the campus’ militant black female character and rabble rouser, explains near the end of the film to the dean of students the essential problem: “That invite should have been met with derision and outrage. Instead, a 100 people — your students — showed up, and they pulled out posters and decorations and costumes that they made for such an event and they showed our school exactly where it’s at.”

Before we can dismiss such an incident as nothing more than a fictional event conjured from the mind of first-time director Justin Simien, the film tethers it to reality at its end by interspersing pictures of recent blackface parties occurring at various colleges: Dartmouth (2013), University of Florida (2012), Penn State (2012), University of Southern Mississippi (2011), and University of California at San Diego (2010).

Dear White People‘s uncompromising presentation of everyday and systemic racism earns it a unique place among Hollywood films that normally try to quarantine contemporary racism as an aberration of a few demented individuals. The campus of Winchester University serves as a microcosm of larger racist forces. For instance, the campus’ white president naively dismisses concerns over racism as a bygone issue until the blackface party proves otherwise, a painfully accurate summation of a disposition that many U.S. legislators and business leaders similarly possess. The use of a college campus as a petri dish to explore deeper racial tensions has been employed by various black directors, namely Spike Lee (in 1988’s School Daze) and John Singleton (in 1995’s Higher Learning). Unlike these earlier films, however, Dear White People shows a sophistication and nuance that those films lack, which might in part be due to Simien benefiting from the trailblazing efforts of these earlier directors who forced Hollywood to bring more complex racial themes and African-American concerns to predominantly lilywhite screens.

Dear White People puts the audience on notice from its very beginning by implicating us with the racism occurring at Winchester University. When we first meet Sam White, a junior in media studies who functions as the campus’ go-to “angry black female”, she aims her camera directly at us. Sam’s gaze suggests that the racism she documents with her camera on campus is no different than the racism that consumes the film audience’s lives. Although such racism might often be less visible for those who hold the privilege to ignore it, it courses throughout the American scene before suddenly striking in full view as the recent murders of young black males in Ferguson, Missouri, Brooklyn, New York, Sanford, Florida, and Oakland, California all too readily attest.

The film frequently breaks its fourth wall to stress how the racism it charts converges with our lives. One scene has a frustrated group of multiracial students yell at us in rapid succession: “Fuck Tyler Perry”; “How come the only black movies Hollywood wants to make are ones with black Mammies in fat suits?”; “Or black women in pain, man?”; “So basically, we got black people dying in the past and black people dying in the present.” The film cuts to the beleaguered, white teen working the ticket stand that the group actually addresses. Needless to say, he has no answer. But such a critique draws attention to the relative absence of smart and funny films by black directors that offer a nuanced perspective of African-American life available to general audiences, due to the inherent racism fostered by Hollywood.

The film also breaks from a strict realist approach to at times draw attention to the subtle racism occurring onscreen. For example, Troy (Brandon P. Bell), an upper-middle-class black student who feels his life constantly being measured against the weight of racial stereotypes that his father meticulously draws to his attention, dates Sofia (Brittany Curran), a rich white girl, the daughter of the university’s president. As we are initially introduced to them, Sam’s voice cuts in from her radio program, Dear White People, announcing: “Dear White People, This just in: Dating a black person to piss off your parents is a form of racism”.

Clearly, such an announcement stretches credibility if one is to suppose that Sam actually happens to be saying this at the exact moment that we meet Troy and Sofia. Furthermore, the couple occupies a space without any visible speakers to transmit Sam’s voice. Instead, however, we should consider Sam’s voice as operating as a racial superego that periodically punctuates the film by drawing our attention to the unconscious ways in which racism deeply structures many of its characters’ everyday interactions. What might at first appear the symbol of racial progress—an interracial couple—should not be taken at face value since much more complicated hidden desires direct their relationship. Just as Sofia uses Troy to rebel against her father, we soon learn that Troy similarly uses Sofia to gain access to her brother, Kurt Fletcher (Kyle Gallner), the editor of Pastiche, the magazine that Troy wants to join. Their relationship is nothing but subterfuge, with each mutually using each other as pawns for their secret agendas.

As the movie moves into the textures of the characters’ lives, its portrayal of racial issues grow increasingly complicated and nuanced. Sam’s militancy, for example, although justified on many different levels, is also seen as a form of overcompensation to assert a black identity against her embarrassment of having a white father. Her white heritage not only manifests itself through her lighter skin, but also through her last name, which serves as a permanent reminder that her identity cannot easily fit into limited black and white categories.

Her incendiary rhetoric helps her avoid such issues by firmly lodging her into a black collective identity. Brilliantly, Simien visually relates how such rhetoric both provides a sense of collective empowerment and individual escape when Sam runs for head of household of the black residence hall. She initially stands nervously onstage with her hands locked behind her back before launching into her attack on Troy, the Randomization of Housing Act that threatens to eliminate all-black residence halls, and the entire university apparatus. She orates, “This wasn’t motivated by a desire to mix things up, bring about racial and socio-economic harmony. No. The black kids are sitting together in the proverbial cafeteria so they must be up to no good… Black kids get their own house and suddenly we got a problem?… All we have is a dean who would rather please his massa than stand up for his own.”

As she speaks, the camera slowly climbs as if her words are rousing Sam to move outside of herself. The rhetoric unites Sam with the radical students of the Black Student Union, as if creating a transcendental force that moves beyond any one individual by uniting them collectively with her words.

Yet, at the same time, this outer body experience also fails to acknowledge Sam’s own mixed desires such as enjoying white cultural fare like Robert Altman films and Taylor Swift songs. While defending the importance of an all-black space, the rhetoric steamrollers over how such an easily definable and pure psychic space does not exist for Sam or any of the other black characters. The rhetoric, in other words, is both true and false simultaneously in its identifying a justified need for an all-black space while overlooking how such purist notions do not align themselves entirely with our libidinal desires.

Sam’s internal racial divide further manifests itself in her sleeping both with Reggie (Marque Richardson), a black militant who is more bluster than substance, and Gabe (Justin Dobies), a white graduate student who works as a teacher’s assistant her video production course. Sam gradually abandons her radical posturing while maintaining her insightful critiques of racist dynamics found on campus. She stops wearing hair extensions that artificially sculpt her hair in what she considers a more Afro-centric style and finally holds hands with Gabe in public, suggesting her ease with their relationship.

Coco (Teyonah Parris) has vexed relations with others for similar reasons. She desperately attempts to hide her working-class background of coming from the south side of Chicago. She shortens her name from Colandrea to Coco. As she explains, “My parents should have just named me ghetto-ass hoodrat-ass Aneisha.” Although she lives in the black residence hall, she constantly cruises for white boyfriends to distance her from her past.

Coco (Teyonah Parris) playing into stereotypes to draw hits for her video blog

She frantically wants to step outside herself through her video blog. This gets visualized as she speaks to a reality television producer. Her image is framed in a mirror as she tells him, “I think I would be good TV.” She wants to become all surface, pure spectacle, in order to anesthetize the anxiety that her lower-class, black background entails. Ironically, she has to embody black female stereotypes, like wearing a blonde wig and speaking with a more ghetto dialect, to increase viewer hits and interest the producer.

Here, the film becomes incredibly meta-critical in its suggestion that the only way in which black people can gain any kind of mass distribution is by perpetuating the very racist imagery that they want to challenge. (Spike Lee’s Bamboozled [2000] and Julie Dash’s Illusions [1982] both brilliantly explore this same concern). As we learn during the DVD extras, this outlook also helps explain why it took many years for any producer to fully fund Dear White People: it doesn’t ascribe to a ready-made racist formula that much commercial media bolsters.

Dear White People explores the devastating psychic ramifications that such racism has upon individuals. It leads Sam, counter to her appearance of being fully self-aware, to hide her relationship with Gabe. It leads Coco to assert that “I am not really into black dudes” as she flirts with Troy. Tellingly, she ends up sleeping with him in the next scene. This suggests that her sexual desires and personal ambitions often battle against one another. But, to give her credit, she tempers her ambitions in recognition of how such desires cannot be easily contained. Rather, they should be acknowledged.

Sadly, Troy continues to repress his own desires by supplicating to the needs of his father. For his dad, Troy symbolizes a breathing positive image against the oppressive weight of centuries of stereotypes. Troy’s life is no longer his own. He sacrifices it to what is perceived as “the greater good of the race”. The film shows the costs that accompany seemingly unequivocal success: the rejection of the complex and contradictory desires that make one human.

Simien stumbles at times when using melodramatic convention to overstate Dear White People‘s point. For example, Troy’s father is the dean of students at Winchester while Kurt’s father is president there, too. The rivalry of the fathers, who also happened to attend college together, are bequeathed to the sons. Furthermore, the film stresses the racial inequality that leads Kurt’s academically mediocre father to become university president over that of Troy’s father, a smarter and more qualified person, who gets relegated to the position of dean. Although such conventions make certain metaphorical sense of visualizing how the racial past haunts later generations and racism inflects job opportunities, they come off as hollow and a bit rote, more to make a point than to develop these characters.

Overall, however, Dear White People reveals an incredibly talented new director at work. The DVD extras show the ingenuity of Justin Simien, who created a fake trailer and mock public service announcements called “The More You Know (About Black People)”, to generate interest among future investors in order to complete the film. The fact that the movie was finally made with Simien’s original vision fully intact speaks to his skill not only as a director, but also as someone who can successfully navigate the backchannels of Hollywood to have his project come to fruition. Dear White People’s ability to balance character-driven stories with didactic critiques against the racist practices that haunt our daily lives speaks to a sophisticated outlook rare among first-time directors. One can only hope that Hollywood recognizes this too, so that Simien will be given the opportunity to direct a second feature in the near future rather than be caught in the artistic limbo that has often plagued black directors like Robert Townsend and Julie Dash in the past.