“Keep Austin Weird”. That slogan, along with bumper stickers promoting it, started appearing around the city years ago to promote local businesses and as a challenge to rising gentrification. When did Austin start to get weird, though? One can probably trace a lot of the weirdness to the late ‘60s, when Texas hippie culture found a welcoming home in the capitol city. The artists and musicians associated with the youth movement filled up the burgh, migrating in from parts distant and near, transforming Austin into a liberal oasis in the otherwise staunchly conservative state.

For, even though San Francisco, New York and Boston all had thriving technicolor counterculture scenes happening at the same time, Austin’s scene was particularly unique due in large part to its Texas location. Austin music and arts became a product of cowboys and rednecks commingling with the hippies and freaks – often harmoniously. Sometimes they were one and the same. This was especially reflected in the poster art advertising concerts which, though inspired by posters from famous venues such as San Francisco’s Fillmore and the Avalon Ballroom, had a uniquely Texan slant. Western themes and symbols (deserts, cowboys, horses, armadillos) were often used and appropriated into the new culture, the artists changing them and psychedelicizing them, making them fit into a vision entirely different and new.

Homegrown: Austin Music Posters 1967 to 1982, edited by Alan Schaefer, is a retrospective of the most fertile years of Austin poster art. With extensive essays by music journalist and radio host Joe Nick Patoski and Nels Jacobson, poster artist and founding director of the South Austin Popular Culture Center and the American Poster Institute, the historical significance of the artists is detailed, along with biographical information on many. The bulk of the book, though, of course, is the posters themselves. Examples are lovingly displayed full-page with detailed citation information for each including poster artist, musician, venue, date and original size. Speaking of original size, art director Gilbert Shelton recounts in Patoski’s essay that, apart from subject matter, another way Austin posters differed from the more well-known posters in San Francisco was that “…being in Texas, we decided to make our posters twice as big as the California posters.”

Two venues in particular provided the impetus for the creativity coming to fruition in poster art. The Vulcan Gas Company was an early focal point, hosting light shows and original music and booking bands big in San Francisco. When the Vulcan closed its doors in 1970, the new Armadillo World Headquarters quickly took its place as the hot venue and had a successful ten year run, producing hundreds of posters advertising the acts it booked.

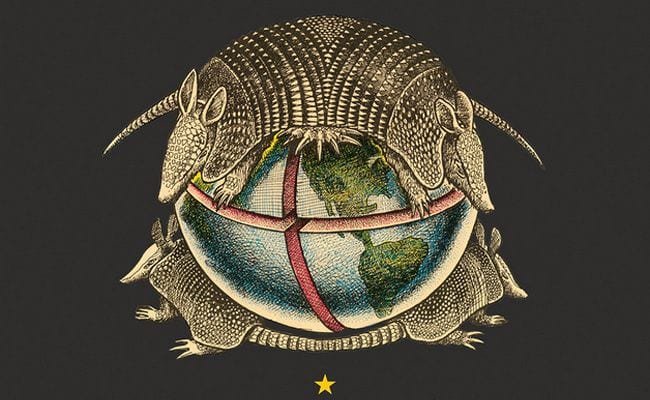

Homegrown features a painter’s pallet of different artists, many associated with the Vulcan and the Armadillo, including Jim Franklin, the godfather of Austin music poster art. Franklin’s work of cross-hatched pen and ink drawings was often surreal, even as it always maintained an anchor in realism. He became known for his trademark armadillos, making him a natural choice to design the poster for the Armadillo World Headquarters opening night, which featured four armadillos joined together and encircling the Earth.

Other artists favored pen and ink as their media of choice, as well. Danny Garrett’s work was in general less surreal than Franklin’s and informed by art nouveau and 19th century typography. Micael Priest and Kerry Awn’s endlessly imaginative pieces were often jam-packed with head and eye expanding detail. Ken Featherstone’s work often featured finely shaded cross-hatched portraits of the bands and musicians who were playing in the clubs around town. A uniquely Texas vision colors most of these ’60s and ’70s posters, with cannabis cowboys, guitar-slinging musicians, and desert landscapes.

In the late ‘70s and into the ‘80s, Austin poster art underwent a transformation when punk rock became the music of choice for much of the youth. Punk’s aesthetic was often at odds with the psychedelic art associated with the earlier wave of bands and poster artists. It was more confrontational and drew on more raw artistic styles, including collage and comic book art. Budgets were also more limited in the punk world and there was more of a DIY ethic. Posters more commonly became handbills, which needed to be easily and cheaply photocopied.

Austin is known as the “live music capital of the world” these days, a designation arrived at in no small part due to the married legacy of poster art and music illustrated in Homegrown. As Alan Schaefer writes in the preface: “A history of the city’s music scene and a narrative of cultural signs can be viewed in these works.” Nels Jacobsen’s “Colorful Tales and Early Techniques” essay in the book expands on that statement by noting “As music drove the poster movement, Austin’s artists elevated Texas street art to an unprecedented status and relevance. Through their powerful designs, these posterists spoke to hippies, rednecks, punks, and passersby; they provided a paper-prefiguring of every advertised performance and a dated visual trophy with which to commemorate each event after the fact. Long before computer graphics and digital art, Austin poster artists, wielding only pens, pencils, and X-Acto blades, constructed by hand a sprawling illustrated monument to Austin music and culture.”