Excerpted from Unbuttoning America: A Biography of “Peyton Place” by Ardis Cameron © 2015 (footnotes omitted), and reprinted by permission of Cornell University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reprinted, reproduced, posted on another website or distributed by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

The Novel Truth

When I read [Peyton Place] at ten years old, I knew the world around me was a lie.

— John Waters

In the autumn of 1956, Mrs. John L. Harris sat down to read Peyton Place, but her reading was fraught with difficulties. Her son, a student at Dartmouth College, “was disgusted,” she wrote its author, “and my husband wasn’t much better pleased.” Distracted and annoyed by the men in her family, the Seattle housewife nevertheless found the story “completely fascinating,” while the writing “caused me to fairly race through the pages.” Peyton Place’s critics had simply missed the point, she fumed. “The so-called ‘filth’ which many people censure in your book is to me only a small part of a truly good story.” Mrs. Harris urged Grace Metalious to carry on. “Please keep writing,” she implored. “Your talent is too good to hide.” Then she sat down to read Peyton Place a second time.

Mrs. Harris was hardly alone. “Finding nothing about to read on a dull evening,” Frank Allen picked up a copy of Peyton Place that someone had left behind at his New Hampshire summer camp. He had avoided reading the novel for almost three years after his favorite literary critic, Parker Marrow, panned it. “After a few pages,” Allen exclaimed in a letter to Metalious, “I whistled in astonishment and thought that so & so parker! he ought to be shot … I have taken up cudgels in your defense ever since.” Even the harried cookery book writer Julia Child found in Peyton Place the perfect “reading-for-pure-self-indulgence.” Finding a copy in paperback a year after its publication, she recommended it to her friend Avis DeVoto. “Quite enjoyed it,” she confessed. Then, her vacation over, Child “soberly and happily” returned to Goethe.”

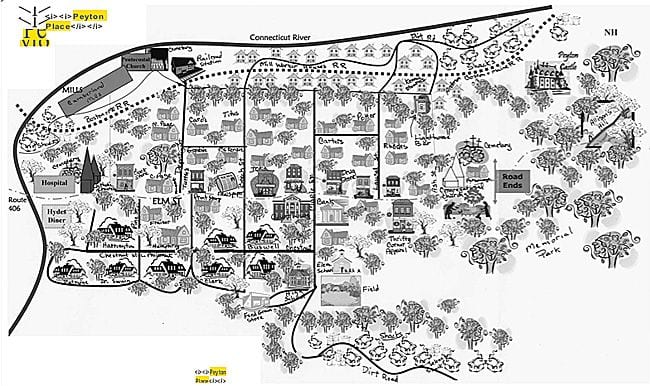

Figure 1. For some readers, Peyton Place was real enough to map. Map of Peyton Place by reader Deborah Briskey. Gift to the author.

Despite its reputation as a form of leisure, the reading of novels has never been a trouble-free activity, especially for women, whose readerly desires and habits have long been the subject of passionate concern and controversy. Almost from the first stirrings of the genre, the novel irritated people of quality. “Novels,” the Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush warned his readers, should be avoided at all costs, for rather than “soften[ing] the female heart into acts of humanity,” novels “blunt the heart to that which is real.” What made the new genre “novel,” in other words, was its focus on the imaginary and invented realms of human life, putting the novelist in tension with eighteenth-century calls to reason, evidence, and truth. Things only got worse. By the nineteenth century, fiction was jamming empiricist aspirations to objectivity and fact like dirt in a trigger. “History, travels, poetry, and moral essays” became, as Rush recommended, the preferred antidote to “that passion for reading novels which so generally prevails among the fair sex.”

Republican mothers were no less vexed over the types of fiction that women readers preferred. Popular novelists like Hannah Webster Forster wrote extensively against the dangers inherent in certain books. She lamented “the kind of reading now adopted by the generality of young ladies,” which to her mind was “foreign to our manners.” Susanna Rowson worried as well that the reading of novels could “vitiate the taste and corrupt the heart,” joining Foster in decrying the ability of novels to promote among female readers “impure desires,” “vanity,” and “dissipation.”

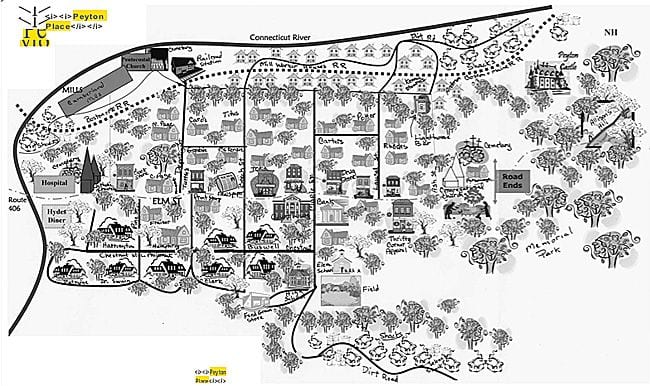

At the heart of these debates was the assumption, driven by Enlightenment concerns over the relationship between reason and passion, that fiction, especially romantic, gothic, and sensational novels, overly engaged the imagination of readers, making it difficult, if not impossible, for the untutored and “primitive” to distinguish between fact and fiction, fantasy and reality. Unlike the normative educated male reader, whose reasoning capacity, it was argued, provided a more critical rendering of such materials, female, working-class, and subjugated readers were said to lack the capacity to curb readerly flights of fancy. For them, novels reduced the rational self to the imitative behavior of the “captive audience,” whereby readers, too caught up in the thrills of fiction, forfeited their capacity to engage the narrative in a reasonable and productive manner. “For all of these lesser subjectivities,” scholars have made clear, “the exercise of the imagination was problematic.” The credulous reader could literally get lost in a book, so closely did she identify with character, plot, and scene. Even the sober mill girls of New England, it seems, fell under the sway of sensational reading, as newspaper cartoons like the one shown here invited readers to draw connections between cheap wages and cheap fiction at the very time when Lowell manufacturers were seeking to prove the moral as well as the monetary benefits of female wage labor. Nothing good, it seemed, could come from the irrational mental wanderings of fiction, for “novels not only pollute the imaginations of young women,” one American critic warned, but also give “false ideas of life.”

Figure 2. Caricature of Lowell factory girls reading “cheap literature.” The woman on the left is reading a French sex manual, while the pair in bed share a racy novel by Joseph Holt Ingraham. “Factory Girls,” cover, Boston City Crier and Country Advertiser, April 1846. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

In the summer of 1905, Henry Dwight Sedgwick had had enough. Readers, he lamented, were nothing more than an indiscriminate “mob” rushing here and there in pursuit of the latest best-seller. “The proletariat, the lower bourgeois, and the upper bourgeois,” it mattered not at all, he wrote, for each class had abandoned its better instincts and training in quest of the “mob novel.” The numbers, Sedgwick reported, were shocking: “The Crisis, 405,000 copies sold, the Eternal City, 325,000, the Leopard’s Spots, with its career still before it, 94,000.” Like many of his literary brethren, Sedgwick worried over the state of American Letters and the nation that produced them. He explicitly linked the turbulent mass strikes that rocked his generation with the consumption of cheap novels and sensational stories, warning readers against the “Mob Spirit” that now engulfed Literature. In the grip of cheap fiction, he charged, the reader grew “more tumultuous, more passionate, more a creature of instinct and less a creature of reason.” The “reading mob the bigger it grows, becomes more emotional, more excited, it reads and talks with greater avidity, is increasingly vehement in its likes and dislikes, and opinions, forces the book on its neighbors, gives, and lends more and more with the swift and sure emotions of instinct.” Fiction had become a “contagion” spreading itself across the classes and undermining the educational efforts of schools and intellectuals.

Sedgwick was born in 1861, seven years after the founding of the Boston Public Library, and his career as a lawyer, essayist, and historian paralleled the great boom in literacy and the mass marketing of books. Cheap paper put romance stories and dime novels into the hands of increasingly large numbers of working-class and immigrant readers, while free lending libraries not only expanded the reach of books but also gave local librarians the power to decide what kinds of books the public might check out. Publishers listened while library donors cringed. When Samuel Tilden learned that 90 percent of the books borrowed from the Boston Public Library were fiction, he came close to canceling his $2.4 million bequest to New Yorkers who hoped to establish their own free library. Literature, Sedgwick concluded, needed new leadership: “men of natural gifts and educated taste, experienced in the humanities,” who could “tame the turbulent mob spirit” as it coursed through the veins of American social and literary life. Literary men, that is, who shared his passion for Democracy and presumably the Atlantic Monthly. Bad novels made bad citizens.

For those who sought to inflame the laboring mobs, cheap novels were blamed for making shoddy activists. Born in Russia, Rose Pastor came to the United States as a young girl of twelve and quickly found work in the cigar factories of Cleveland. Like Sedgwick, she was a “serious” reader, who turned her love of words into the literary arts, writing poetry and eventually advice columns for the Jewish Daily News in New York City. Moving to New York in 1903, she became active in the Socialist Party, writing on behalf of the working classes as an advocate of radical social change. Already popular among working girls on the Lower East Side, she became their heroine when she married the millionaire James Graham Phelps Stokes. Like Sedgwick, however, Pastor worried over the enormous popularity of cheap fiction and its effects on women and girls. Joining a growing chorus of progressive reformers and union leaders critical of working girls’ participation in consumer culture, especially their “frivolous” pursuit of fashion and romance novels, Pastor feared that dime novels would turn wage-earning women away from political struggle and working-class organization. As Nan Enstad notes, labor activists viewed stories that “offered a fantasy of magnificent wealth bestowed on the working-girl heroine through a secret inheritance and marriage to a millionaire” with condescension and suspicion. Serious times demanded serious books. “With our free circulating libraries,” Pastor scolded laboring women in 1903, “what excuse is there other than ignorance for any girl who reads the crazy phantasies from the imbecile brains of Laura Jean Libbey, The Duchess, and others of their ilk! … I appeal to you—if you read those books—stop! stop!”

It was not to be. Pastor’s own marriage seemed the stuff of fantasy, her continuing radicalism living proof to readers of Laura Jean Libbey that fiction carried with it certain truths their own lives had yet to reveal, certain possibilities that might yet be played out. Readily available from pushcarts and newsstands throughout immigrant and working-class neighborhoods, dime novels joined pickles, bread, and eggs among the necessaries of daily life. But was Sedgwick right? Did cheap novels make for cheeky citizens?

Not surprisingly, proponents of women’s rights were there from the beginning, defending a woman’s right to read whatever her heart desired, more or less. But the relationship between fiction, fantasy, and femininity raised for feminists as well a number of troubling questions. Could the reading of gothic, romantic, and sensational novels, Mary Wollstonecraft and Jane Austen famously wondered, turn the female reader into the degraded “object of desire,” leading to a “conventional, dependent, and degenerate femininity”? Echoing Rose Pastor’s fears, Betty Friedan saw in the “sex glutted novels” of the post–World War II era a serious erosion of “independent activity” among American women which forced them to find “their sole fulfillment through their sexual role in the home.” Consciously catering to the “female hunger for sexual phantasy,” Friedan opined, Peyton Place was another sad symptom of the feminine mystique. In the minds of both progressives and conservatives, in other words, fantasy and imagination could have only negative effects. In the minds of the former, they stirred up erotic and romantic emotions that supplanted reason, promoted female passivity, and undercut a woman’s autonomy and emancipation, while to the latter group of thinkers they inspired “ambitious excess,” provoking not only “disgust for all serious employments” but also a general dissatisfaction with one’s station in life. Only in recent years have attitudes toward the female reader begun to shift. Indeed, entire forests have surrendered themselves to the scholarly exploration of female acts of reading and the everyday uses of books. Secondand third-wave feminists have been especially astute in rethinking the effects of fantasy, repositioning the female reader as a complex social actor who is neither the passive receptor of textual messages nor extraneous to movements of social change. Light fiction, it turns out, is serious business. For women and girls, who stood in the imaginative center of modern consumer society—men produced, women shopped—dime novels and newspaper stories called new attention to their spending habits. Hardly reflective of reality, the gendered narratives of consumption nevertheless gave women and their interests an unexpected edge by placing both at the center of modern consumer culture and rising concerns over its unpredictable emotional and psychic effects. Sharp dichotomies took hold: Was modern consumerist society and the “mass culture” it unleashed a new opiate or a potential site of rebellion and transformation? Labor historians have most often sided with Pastor, assuming, as her Enlightenment predecessors argued, that political engagement and collective action presupposed a coherent and fully formed political identity as “worker,” “woman,” “American.”

Ladies of labor and girls of adventure, however, tell a different tale. In her powerful study of labor politics in the early twentieth century, Enstad shows that dime novels, like clothes and movies, offered girls and women who labored in constrained circumstances a way to negotiate contradictory positions. Building on the work of Wendy Brown, Judith Butler, and Joan Scott, Enstad underscores the mutability of subjectivity, arguing that women’s political consciousness and actions emerged less from “clear and coherent identities” than from the contradictions laboring women experienced as terms like “worker” and “working class” increasingly took on meaning in opposition to womanhood and all things feminine, including the consumption of dime novels. “Precisely because working ladies found themselves excluded from the honorable categories of ‘worker,’ ‘American’ and ‘women,’” writes Enstad, “the resources of popular culture were of particular importance in their efforts to claim identities out of contradictions, and gain a sense of dignity and worth.” Unable to make sense of the categories available to describe their experiences as both wage laborers and American ladies, immigrant girls fashioned a “particular form of radicalism and their own gender and class language.” With fiction and fantasy, girls of toil spun new dreams and conjured different selves, reworking old identities as they went and fashioning new, aspirational, and at times political subjectivities. From this perspective, subjectivity unfolds as a process linked to “self ” and “identity,” but it accentuates more than either the never-ending momentum of becoming. Novels did not cause working women to go on strike in 1909, but in their ability to articulate scenarios of readerly desire, they allowed laboring women to imagine themselves in new ways. In the fantasies of fiction and fashion, female readers found common ground and a collective desire that captured—perhaps produced—their imagination as “women” in common cause. At the beginning of every good story is a reader’s silent longing.

To tell the truth, readers were always a mixed lot. There was never a “universal reader,” and the concept of “the female reader” was pure fiction, the rejected Other who gave to the serious reader its privileged identity. Reading itself is a deeply mediated activity. Habits of reading reflect differences in class and ethnicity as well as in gender and individual psychology. The segmentation of publishing, as Lawrence Levine pointed out, was well advanced by the turn of the twentieth century, and the notion of “the female reader,” like the “mob reader,” misrepresented both readership and the literary marketplace. Still, in the long and furious battle over Good Books and the dangers of reading invention and “phantasy,” the “woman reader” emerged as an undifferentiated subject of concern and complaint. Historically bound together by the fetters of criticism, women across classes and regions, ethnicity, race, and sexualities now found themselves yoked together as problematic consumers of questionable taste. To pick up a “best-seller” was to confirm and mark that identity linking disparate women together as frivolous readers and femininity with the trashy and lightweight. Real men read history.

Let them. The girls of toil and the ladies of leisure cared not a fig. For where, if not in novel form, could the female reader find herself an actor in a world where women’s actions mattered? How else except with a novelist’s pen was the history of women written? Where else did the concerns of the female reader find a telling? Of what use, George Eliot asked her readers, was Casaubon’s expanding index file of “facts, facts, facts” to the busy women of Middlemarch, whose purposeful lives passed in front of the historian’s gaze without note or notice? Of what use was History for those edited out of its pages? Novels spoke to women because History had nothing to say to them. “Women were not only not interested in history,” the historian Jill Lepore writes, “they didn’t trust it.” It simply didn’t speak their language. Represented as the antidote to the stormy passions and turbulent falsehoods of fiction, History lashed itself to the oak-like mast of hard fact. It cleared its decks of subjectivity, fantasy, and desire and jettisoned undocumented lives. Women were the first to lose interest. “It tells me nothing that does not either vex or weary me,” Jane Austen’s heroine Catherine Morland confides in Northanger Abbey. “The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all—it is very tiresome: and yet I often think it odd that it should be so dull, for a great deal of it must be invention.” Fiction was interesting because it gave a telling to things History would not. The coquette, prostitute, spinster, society matron, factory operative, slave girl, parson’s daughter, woman in the attic, girl detective, and woman behind bars all found a place in the popular archive of fiction. The difficulties readers encountered were but flies in honey. Women read the critics, heard the debates, suffered the slings and arrows of husbands and sons, and then, like Mrs. Harris, settled into the hidden lives and secret truths that every truly good story promised.

Like the category “woman,” then, the “female reader” constituted an act of social engineering, shaping and defining over time the hierarchical contours of gender difference and the essential nature that separated the feminine realm from that of the masculine. But as Enstad and others have shown, the reading of melodrama, gothic, romance, and sentimental fiction could just as easily alter a reader’s relationship to both. “Don’t tell me that woman wasn’t happy!” the deserted husband of Lulamae tells the young narrator in Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s. “Reading dreams. That’s what started her walking down the road. Every day she’d walk a little further: a mile, and come home. Two miles, and come home. One day she just kept on.” Lulamae did not simply follow her dreams, nor is it the case that stories made them up for her. Rather stories are always produced in the exchanges between text and reader so that both are subject to change, each the shifting product of fantasy. Is there ever one meaning locked into any given story? Is there truly ever one reader? In the textual fantasies Lulamae wiggled herself into, the “clear and invariable” wife her husband knew wobbled and disappeared. If Lulamae couldn’t make it down that road, Holly would go lightly, finding in her new name itineraries Lulamae could only dream about. The “fictive securities of reality,” as Michel de Certeau put it, slip away in the reading of books, taking with them “the assurances that give the self its location on the social checkerboard.”

Sex upped the ante. “Reading, dear reader, is a sexual and sexually divided practice,” the literary scholar Cora Kaplan writes as she sets out to probe her compulsive reading habits when, as a teenager in the 1950s, fiction became an especially powerful force in her life and “narrative pleasure lost its innocence.” She confesses, “Peyton Place, Jane Eyre, Bleak House, Nana: in my teens, they were all the same to me, part of my sexual and emotional initiation, confirming, constructing my femininity, making plain the psychic form of sexual difference.” Longish, robust novels like these collectively invited readers to identify with multiple characters, and unlike the formulaic “romance novels” of more recent years, they seldom confirmed conventional gender or sexual norms. “Rather,” Kaplan argues, “they evoke powerful overlapping scenarios in which the relation of reader to character is often deliciously blurred.” Novels, Kaplan theorizes, helped female readers like herself “to identify across sexual difference and to engage with narrative fantasy from a variety of subject positions and at various levels.”

Few readers can match Kaplan’s self-awareness or capture her astute rendering of the social and psychic implications of youthful reading. But as we shall see, she was not alone in reading herself into a sexualized womanhood and, in the case of Peyton Place, into manhood as well. Readers tell of devouring Peyton Place with “heart pounding and hands straying,” and in its pages coming to terms with what those inexact yet powerfully rooted concepts meant and would come to mean as they repositioned themselves within the unconventional scenarios the novel evoked.

In the language of many critics, however, Peyton Place was simply a “sexy” book. While serious literary critics like Carlos Baker linked Peyton Place to “the revolt from the village school” and compared the young author to literary lights like Sherwood Anderson, Edmund Wilson, John O’Hara, and Sinclair Lewis, the novel found cultural traction as a salacious, spicy, even “sexsational” novel, a reputation the publishing industry kindled. Even before it hit the bookshelves, the novel was marketed as so shocking that it had caused the dismissal of the author’s husband from his teaching job. Pictures on the front pages of New England newspapers showed a smiling Grace Metalious surrounded by her family and her unemployed husband, George. What kind of wife could do such a thing? What kind of mother could write such a book?

Journalists, too, increasingly connected Peyton Place to a category of erotically infused novels loosely defined as “sex novels,” best-sellers from Anthony Adverse and Whistle Stop before the war to Forever Amber, Kings Row, The Amboy Dukes, and Mandingo in the years that followed. Uneven in skillfulness and literary acclaim, they were united by their willingness to explore the intimate frontiers of everyday life. Where Whistle Stop adopted a gritty social realism that only hinted at sibling incest, Forever Amber used a sexually explicit language of pragmatic realism to relate, according to the attorney general of Massachusetts, “70 references to sexual intercourse, 39 illegitimate pregnancies, seven abortions, and 10 scenes in which women undressed in front of men who were not their husbands.”

The Lie That Tells the Truth

Wildly popular, sex novels mirrored the narrative conventions of earlier romance, melodrama, and sentimental literature, but in these sprawling page-turners readers found complex, often dark stories with a plethora of characters who reflected the public’s growing fascination with human sexuality and abnormal psychology. This was especially true in the years after World War II, when the Kinsey Reports and sex-change surgery ignited new interest in sexuality in general and in unconventional sexuality in particular. Sex novels and sexually frank magazines like Playboy invited readers to enter the intimate lives of the sexually diverse and socially deviant in ways unavailable in most mainstream newspapers and magazines, which, in many rural areas and conservative regions, underreported and toned down scientific studies like those of Alfred Kinsey.

Indeed, part of the “rawness” of the sex novel was its ability to represent human behaviors and emotions “in the flesh,” as it were: as knowledge unprocessed and unadulterated by social probity and conventional politeness. “Dirt” took readers down below, where the unfiltered truth was hidden. Desire and difference hovered over every page—sexual desire to be sure, but also the kinds of yearning and dislocation not easily translated into political understandings. And unlike the pulps, which they tend to be confused with, many of the so-called sex novels were published by quality houses like Macmillan, Random House, and Julian Messner, and sold as hardbacks and paperback reprints in department stores and respectable bookshops rather than being confined to male-dominated spaces in train stations and drugstore news racks. Indeed, it was their proliferation as much as their content that made them so explosive, provoking one astute critic to describe them as the “Literary H-Bombs” of the twentieth century. To be sure, Peyton Place had its sexy bits, and its opening lines are among the most erotic in the novel:

Indian summer is like a woman. Ripe, hotly passionate, but fickle, she comes and goes as she pleases so that one is never sure whether she will come at all, nor for how long she will stay … One year, early in October, Indian summer came to a town called Peyton Place. Like a laughing woman Indian summer came and spread herself over the country-side and made everything hurtfully beautiful to the eye.

Metalious could write in a style that was “steamy, suggestive, and vague,” and her dialogue ranged from the shy and reticent language of adolescence to the tough-guy candor of the hard-boiled detective. “The most spiced-up story of all time,” a teenager called it in a letter to the author. An older fan from Springfield, Oregon, was equally thrilled to find the book “liberally sprinkled with sex.” Having read the novel twice, she wrote to thank “Grace,” assuring the controversial author that her efforts had not been in vain. “I learned a few things from your book that I will not soon forget,” she confided. “Oh, Grace, I salute you!” Self-styled sophisticates wrote to congratulate Metalious on getting sex right. “American women are beautiful,” a French-born reader conceded, but when it comes to the “art of love,” they disappointed. “In this country,” he complained, “there is too much conformity, no imagination, every thing is done with a monotonous sameness.” Scorning the “hacks” who wrote of “sex without the slightest idea of what it’s all about,” the letter writer rejoiced in Metalious’s mastery of the subject, begging her to meet with him to discuss his own efforts to remedy the situation, a “fast story” called “The Vanishing Lover.” Still, not everyone was satisfied: “If you ever launch another book, go a little stronger,” an ex-preacher from Oklahoma City advised. “Include some Spanking Episodes also Oral scenes. Yours truly, C. O. Collins.”

In the recesses of rural libraries, dusty used bookstores, and collectors’ shelves, yellowed dog-eared pages fall open to reveal the underlining and marginalia left by fervent readers from the past. “Ask Katie about this!” the bold hand of Robert S. inked beside the much-memorized line “Your nipples are as hard as diamonds.” Page 203 of his copy took an especially hard pounding as Rodney Harrington, teenage son of Peyton Place’s wealthy mill owner, found the “V” of Betty Anderson’s crotch. And then there was the beach scene Peter W. circled in red ink three times:

“Untie the top of your bathing suit,” he said harshly. “I want to feel your breast against me when I kiss you.”

She had stood like a statue, one hand on the back of her neck where she had put it to fluff out her hair, when he spoke. He did not speak again, but when she did not move he stepped in front of her and untied the top strap of her bathing suit.”

“Mark! Try it out!” he scribbled in the margin of his copy.

The faded enthusiasms readers left behind, earmarked in its pages, evoke the charged atmosphere that hovered over sexual expression at the time and the tensions the novel ignited. “Sex,” Rose Feld declared in the New York Herald Tribune, “is the dominant accent of the book, and Mrs. Metalious, in her effort to be realistic, spares neither detail or language in high-lightening her scenes in bed, car or on the beach.” Peyton Place was “shocking.” Even the future mother of God first found Eros in its pages: “I was lying down on the bed, reading a book called Peyton Place,” rock and roller Grace Slick told interviewers. “It was resting on my crotch and I was reading along and all of a sudden it got me off. For the next two weeks,” she confessed, “I went bananas with it.” Women weren’t the only ones going bananas over the book. Metalious’s biographer Emily Toth tells the story of Michael True who while stationed at Fort Chaffee, Arkansas, in the late 1950s, “could walk down the center aisle of any barracks and see forty men lying on their bunks, all still in army boots, reading the paperback version of Peyton Place.” Like an Indian summer in New England, the men, too, waited for an erotic return.

Still. Yet. When readers talk of Peyton Place or when we read extant letters from fans, an odd quality seeps out. Even in the anger and malevolence of critics, there is an aperçu of desire and longing that seems quite out of proportion to anything contained in even the most sexually charged scenes of the novel. In the fan mail that swamped Grace Metalious, there was little that surprised or outraged letter writers, who, on the whole, seem to have picked up their pens more to confess a certain uneasiness with the novel’s astute rendering of the world than to comment on the licentiousness of the author’s fiction. “The reason it struck people,” the writer John Michael Hayes observed, “was that it was so real. They felt it. It didn’t read like fiction.”

Peyton Place was oddly familiar and yet jarringly strange not only because the novel shocked but also because in the minds of many readers the distinction between the imaginary realm of fiction and the reality of their lives was surprisingly effaced—a reality at best vaguely articulated and at times described as quite “unreal,” there being no words to express certain experiences, and thus no way to mark them off as such. Reading Peyton Place provoked an uncanny recognition, a glimpse into a somewhat frightening realm readers knew existed but could express in only a vague, inarticulate way, a taboo landscape, out of the public eye, that spoke to the silent fears and ambiguous emotions fans struggled to describe. As we shall see, they wrote as if suddenly exposed, expressing both surprise and uneasiness at the range of emotions the novel called forth.

Almost always, their stories begin with subterfuge:

“It was the kind of book mothers would hide under the bed,” a professor of English recalled.

“It was the first time I remember hiding anything from my husband. I kept it in the ice box, behind his beer.”

“I kept it hidden in the basement and used to sneak down there to read it.”

“I always carried it inside a brown paper wrapper. But that became pretty obvious, so my girlfriend and I slipped the dust jacket of Gone With the Wind—they were about the same size—over Peyton Place. But we still got yelled at—my teacher hated Gone With the Wind.”

“Dear Diary,” Ruth Forero wrote in a 2008 letter to the New York Times’ “Metropolitan Diary.” “A few weeks ago on my way to work aboard the downtown No. 4 train, I noticed, across from me, a young woman oblivious to the comings and goings of her fellow straphangers, her face buried in her brand-new copy of Grace Metalious’s Peyton Place. The scene transported me back to my early teens and the forbidden pleasure of reading the book at night with a flashlight under the covers in defiance of my mother’s direct orders that I return the book to the library without reading it because of her strong objections to its supposed lurid content. My,” Mrs. Forero concluded, “what a difference 45 years makes.”

“I kept it under the mattress. It was the only place close to me at night.”

“Oh, I had this big sock I’d use at Christmas. I’d shove Peyton Place down its long leg when my mother came in to say good night. It looked like a snake had eaten it.”

“In the toilet tank. We had one of those old-fashioned water closets, you know. The top had a little shelf where I hid stuff. Peyton Place sat there next to my Playboy magazines.”

“Under my pillow.”

“In a bag. A very deep bag.”

“Way up on the top shelf. My husband was short so he never much looked up there.”

“Under the lower bunk beds in the dorm. The nuns found it anyway and gave us hell. Then they took it back to the convent. We know they read it ’cause the sister who did the cleaning told us she had found it open on a table and what a disgrace it was to see it there. And I think they knew that we knew ’cause nothing was ever said about it and my folks were never notified, which was totally surprising!”

The Irish literary critic Patricia Craig was not so lucky, her expulsion from the convent school in Belfast executed in the wake of Peyton Place. “What has happened?” she asks.

Someone, it appears, has identified me as the owner of a dirty book which went the rounds of Form 5A, and provoked some previously chaste girls to assume an uncharacteristic licentiousness in the back end of Donegal. So the whole rumpus can, after all, be laid at my door. Never mind that I, myself, found the book in question—the lethal Peyton Place—so dispiriting that I couldn’t read it to the end, and had warned would-be borrowers that it wasn’t enjoyable, only bringing it into school under extreme pressure, and then washing my hands of it. (It disappeared; and I never saw it again.)

Virginia Alexander lost her copy going to work. “I read Peyton Place several times,” she told Metalious. “Then I loaned it to the girl on the elevator in my apartment and that was the last of that!”

Peyton Place raced around.

“Almost fifty years ago Peyton Place opened a whole new world for me,” Sarah Goss remembered. “I was a freshman in high school when the book made its rounds through the school. Fellow students exulted in wrestling out the juicy parts of the paperback they kept hidden in their lockers. The best thing you could share with your fellow students was, ‘Read page 187!’ or whatever. As this became more common, it finally occurred to me. Why I should read the whole book! What a story. I hated for it to end. It’s funny—I can’t find the nasty stuff anymore. Anyway, I give that book total credit for my love of reading.”

In such ways did readers advance their education, but it was the furtive nature of their reading that initiated many into the pleasures of subterfuge and the useful arts of daydreaming, fantasy, and transgression. “I was always alone in the library,” the writer Alberto Manguel recalled. “I was twelve or thirteen; I was curled up in one of the big armchairs, engrossed in an article on the devastating effects of gonorrhoea, when my father came in and settled himself at his desk. For a moment I was terrified that he would notice what it was I was reading, but then I realized that no one—not even my father, sitting barely a few steps away—could enter my reading-space, could make out what I was being lewdly told by the book I held in my hands, and that nothing except my own will could enable anyone else to know.” In the wake of this “small miracle,” silent and known only to himself, Manguel “breathlessly and without stopping” tore through Alberto Moravia’s The Conformist, Guy Des Cars’s The Impure, Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, and Grace Metalious’s Peyton Place.

The filmmaker John Waters was ten years old when he discovered Peyton Place on his grandfather’s bookshelf. “I was so shocked, I would sneak and look at it every time.” The first “dirty” book the film director ever read, Peyton Place “electrified” him. “I never got over it.”35 As if to preserve this moment of profound emotion and transformation, Waters framed a small patch of wallpaper a friend had scraped off the study wall of Grace Metalious’s New Hampshire home. Displayed in the privacy of his workspace, the patch emits something of the aura of a purloined treasure which distinguishes it from the mass-produced memento or souvenir. Fans often seek out material remnants of celebrities, yet as Susan Stewart reminds us, it is not the relic or souvenir that is meaningful but rather the narratives of longing and desire that such objects represent. Like any souvenir, Waters’s patch of wallpaper will not function without “the supplementary narrative discourse that both attaches it to its origins and creates a myth with regard to those origins.” Here, in other words, we can find in Waters’s fragment of wallpaper a way to understand something of the power of Peyton Place as a work of personal transgression and transformation. Sought out on a pilgrimage to Gilmanton, delicately removed, hung and framed, the patch takes on the quality of a rare heirloom whose narrative history literally weaves Waters into Metalious’s genealogy and the emboldened terrain her legacy afforded. With each look, the story is reclaimed; with each telling his inheritance secured.

“She put me on the wrong road early on,” said John Waters with a smile, “and I am better for it.”

Not surprisingly, perhaps, it was the publisher of the French edition, Hachette Livre, that most explicitly placed Peyton Place within the domains of transgression and dissidence, of insurgent desire and danger. Retitled Les Plaisirs de l’Enfer, or “The Pleasures of Hell,” the novel was linked not to the fiery home of Lucifer, as American readers might suspect, but rather to the secret archives of the French National Library. On these storied underground shelves, over 350 works of erotic art and writing ranging from the frantic pages confiscated from the Marquis de Sade to early pornographic photography sat cloaked in darkness and under lock and key. Almost every monastery and convent in France held such materials, guarded through the ages in their silent abbeys until claimed by the state. Then, in the 1830s, the National Library decided to isolate all works deemed “contrary to good morals” and tossed thousands of collections into the secret vaults of “Hell.” Few readers ever gained access, and over time, Hell became the stuff of fantasy and legend, “the very place for forbidden thoughts.” A place of mystery, L’Enfer conjured a world of “pseudonyms, wrong addresses and dates, illegal publishing, closed places, convents, boudoirs, jails, but also the world of libraries.” Les Plaisirs de l’Enfer conveyed what many American readers often felt but struggled to express: the promise of secrets unveiled, a drifting away from the known world toward the heart-pounding revelations and forbidden nooks and crannies whispered beneath Peyton Place. “I can’t explain it,” the photographer Robert Monroe confided; “it just seemed to haunt me for a long, long, time, like a shadow.”

In his famous 1956 study The Organization Man, the sociologist William H. Whyte argued that popular novels in the postwar period greatly distorted the realities of American life, often avoiding conflict and increasingly advising readers “to adjust to the system.” Even when domestic squabbles came into view, Whyte charged, their purpose was “merely (to) highlight how lovable and conflict-less is the status quo beneath.” Whyte’s point, often missed in more recent critiques of his work, was not only that the Organization Man was growing uncomfortably conformist but also that realism in popular culture was becoming increasingly fake, a new kind of American fairy tale, an unreal realism. From The Caine Mutiny to the “slick fiction in the Saturday Evening Post,” Whyte found a literature of solace and deception. These “tales are not presented as make-believe; by the use of detail, by the flagrant plainness of their characters, they proclaim themselves realistic slices of life … But it is all sheer romance nonetheless.” Even nonfiction, Whyte believed, was busy mythologizing the placidity of American life, and whether readers believed it or not, realism was becoming hard to find.

Whyte completely failed to mention or honor the many efforts of progressive writers like Arthur Miller, Paddy Chayefsky, Reginald Rose, Richard Wright, Lillian Smith, and others who sought to recast the meanings and boundaries of who and what constituted the typical and ordinary American with a social realism that harkened back to the cultural activism of the Great Depression. But as Cold Warriors increasingly moved to depoliticize popular culture by repudiating the “socially committed representations of the 1930s” and by condemning the so-called affective fallacy of proletarian and ethnic narratives, consumers were increasingly eased into narrowed visions of life along with more benign representations of the system that produced them. Mobilizing against the entertainment industry and exerting increasing control over the airwaves, anticommunist and right-wing forces slowly but steadily seized control over defining the kinds of families that would be represented in visual culture.

As part of a chilling backlash against the liberalizing effects of the war, alternatives to supposedly “traditional” gender relations and “normal” families gave way to benign productions like Father Knows Best (1954–1963), Leave It to Beaver (1957–1963), and The Donna Reed Show (1958–1966), along with older favorites like I Remember Mama (1948–1956), I Love Lucy (1952), The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (1952–1966), and The Danny Thomas Show (1953–1971), all of which emphasized a child-centered home where male breadwinning, female nurture, and domesticity went comfortably unchallenged. Economic hardship, prejudice, and troubled race relations faded from the picture, while class, ethnic, racial, and sexual difference all but vanished from view.

Perhaps no TV show more dramatically illustrated this shift than the enormously popular working-class I Remember Mama, whose immigrant narrative onstage and in print had stood for wartime pluralism and ethnic struggle. In the years that followed the war, however, the show presented a more materialist and maternal Mama ready to defer to the men in a family presented as more contented and less rocked by the economic and social choppiness of the mainstream. Shows that once asked audiences to deal with complex issues morphed into easy confirmations and celebrations of the status quo. New Mama star Irene Dunne endorsed the changes downplaying the role of working-class women in juggling budgets, negotiating with landlords, and maneuvering families through hard times and social conflict. Both onstage and off, Dunne stressed instead women’s role as supporting cast members. “Our main responsibility—also interest,” Dunne told an interviewer, “always will be taking care of the man of the house because the man of the house needs to be taken care of—in more ways than you can shake a stick at.” The Perfect Housewife Institute named her one of the “ten most perfect housewives in Hollywood.”

Like the character she portrayed, Dunne reflected the sharp conceptual retreat described by Elaine Tyler May as “domestic containment,” a politics forged in the wake of postwar changes in women’s attitudes and expectations and by the insecurities they unleashed. As the hydrogen bomb fueled Cold War fears of chaos and decay, family stability and female domesticity became patriotic goals intended to unnerve dissenters as well as dry up funds and opportunities for entertainers and creators of popular culture who pushed for more realistic treatments of contemporary issues. To be sure, undercurrents of discontent flowed. Yet as late as 1957, 80 percent of Americans polled said that people who chose not to marry were “sick,” “neurotic,” and “immoral.” Throughout the 1950s couples married younger and younger, with men taking vows at the average age of twenty-two by the end of the decade, their wives at twenty. “Young people were not taught to say ‘no,’ ” writes Stephanie Coontz. “They just handed out wedding rings.” The “essentially benevolent society” that Whyte saw in popular culture might have been a fiction, but it was one that gained surefooted traction as the decade reached its midpoint.

In the struggle to mold society’s “truths” and map its moral certainties, popular culture has been shown to be a fierce weapon used by weak and strong alike. Though it is remembered as a scandalous book, we forget that Peyton Place was also about a working mother, class injustice, social hypocrisy, religious dogma, and a cast of characters who pushed the boundaries of what Americans were beginning to call “normality.” “Dirty” books kept doubt alive. At their best, they extended the more cosmopolitan visions of the 1930s into postwar narratives that encouraged a rethinking of what constituted both “ordinary family life” and the borders of national belonging. Bringing into public view the “truth” about outsider identities, sexual candor, and social inequity, lesbian novels, pulps, and sex novels in general allowed readers to trespass, if only for a few hundred pages, across the boundaries of the normative and conventional.

Like melodrama and romance, “their art or politics veering dangerously close to a feminized world of commercial soap operas, especially if attention was directed to female rather than male disappointments,” sex novels flew under the progressive radar as lightweight and frivolous, but the unfairness their stories revealed, the landscapes of difference they unearthed, and the erotic possibilities they conjured were seldom without political effect. If nothing else, they kept alternative roads from closing over and disappearing from popular view. Like a hot current under the Cold War, Peyton Place kept conversations flowing. What was normal? What was real? What was true?

In a landscape of social erasure and sexual opacity, fiction, as Jean Cocteau well understood, is often the lie that tells the truth.