There’s long been a standard narrative about jazz and religion in which the black church influenced the early sounds of the genre (and maybe we can throw in some spirituals as influence, too, if we want to dig a little more). Players took their cues from their youthful church experiences and converted that influence into whatever form of jazz suited the era. A “standard narrative”, though, usually just masks more complex interactions. With Spirits Rejoice!: Jazz and American Religion, Jason C. Bivins – a religious studies scholar and jazz musician – thinks through more difficult aspects of the relationships between jazz and American religions, while at the same time examining the permeability of each of those categories.

Bivins explains his twin objectives are “suggesting that we can think about both jazz and American religions in fresh ways, and also raising questions about the study of ‘religions’ themselves.” He wishes “to fabricate new positions from which to engage and encounter” these issues. Tracing the interactions between jazz and religion reveals as many mysteries as it provides answers, which is part of Bivins’s goal (he’s explicit in his desire to provoke conversation rather than to try to answer definitively). The book moves away from issues of influence and into bigger questions of embodiment, even incarnation, and the nature of religion itself.

Defining religion (or not doing so) carries much of the weight of Bivins’ work. As he looks to expand our ways of thinking about religion, he explains, “I often use the gerund ‘spirits rejoicing’ as a synonym for ‘religion’ or ‘spirituality’.” That phrase comes to signify something broader than normative religion. Bivins seeks to expand what we include in the conversation, and uses that phrase to capture the essence of a transcendent reach available through both sacraments and saxophones. He and his subjects are grappling with a spiritual beyond that can’t be articulated, and that does differ from typical “religious” thinking. In canvassing such space, Bivins seeks to find a decontextualized context, to remove the typical strictures of both religious studies and musicology in order to find new ways to address these subjects.

While he expands and loosens our understanding of “religion” (perhaps making our thinking more honest), Bivins analyzes with precision and control. His chapters delineate various themes discovered in his explorations, giving only short space to tying jazz to specific traditions (closer to the standard narrative approach) while spending most of the book exploring other more lived resonances, such as jazz as ritual, communal structures, and the inaccuracy of traditional readings of race and jazz. Bivins identifies “a dizzy surplus of themes, practices, and creations in traditions jazz and religious.”

All of that isn’t to say there isn’t a basic reading of the influence of spirituality on jazz, and Bivins runs through a wide array of artists who created music out of their Christian faith, their Islamic faith, their Buddhist, Baha’i, syncretic, and ambivalent faiths (his writing on John Zorn’s explorations of religious identity as “a different kind of boundary work” is particularly informative). Whether these artists are pushing boundaries, making surprisingly conservative statements, or just creating, like Ellington, their own sacred concerts, they reveal jazz as infused by sometimes challenging flows of religion.

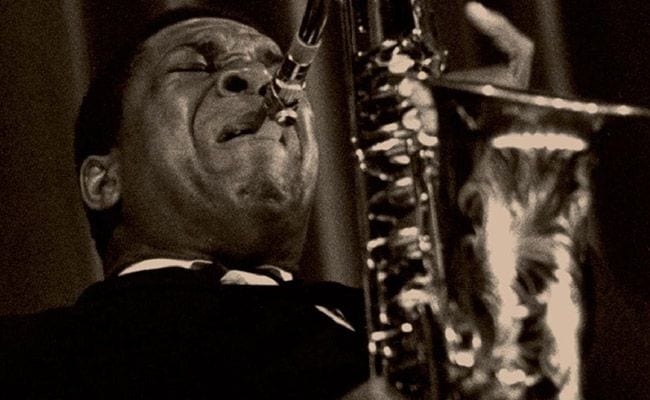

Tenor saxophonist Charles Gayle explicitly drew on his conservative Christian faith to create his music, saying “If the Bible’s wrong, I’m wrong,” and committing “each note” to God. He performed songs with titles like “In the Name of the Father” with the intent to offer it as worship or sacrifice. In similar ways, pianist Abdullah Ibrahim explicitly draws on Islam for his music, which includes devotional pieces such as “Ishmael”, “The Hajj”, and “Imam”.

Tracing that sort of clear religious heritage is fundamental to Spirits Rejoice! only as a starting point. The inseparable intertwinings of jazz and religion take form in practice, and in seeking out those practices and experiences, Bivins writes that “improvised musical performance facilitates becoming religious, just as religious self-understandings can facilitate becoming musically fluent.” He points to Sonny Rollins’ noted non-specificity in religious practice. Rollins says, “My music is my yoga … my way of doing all of these spiritual things.” In the unstable edges of improvisation and the gauzy borders of religion, there is something that can be embodied in the practice of ritualized acts, whether music or something else, or (better) music as something else.

Saxophonist Ellery Eskelin, for example, doesn’t define the borders of jazz and religion for himself, but says, “I crave an integrated experience.” Eskelin’s music isn’t particularly religious – song titles and musical quotes don’t reveal anything of the sort – but finds the physical expression to be spiritual in its transcending “the limitations of language and self”, as Bivins puts it. Ellery’s latest album, Solo Live at Snugs, contains a track called “State of Mind”. There are no outward indicators of the spiritual here, but knowing of Eskelin’s meditation, yoga, and Zen interests suggests that the song – in practice – is a spiritual performance. Bivins’ work would suggest that as an example of spirits rejoicing, despite the lack of traditional religious definitions.

It’s a big assertion, though, and one that Bivins largely succeeds in supporting through the second half of his book. The gray area between “religion” and “spirituality” remains, however, as Bivins takes a reasonably contemporary view on religion. He’s less focused on institutional, organized faith than that term frequently implies, even at times foregoing a sense of god or the supernatural (while maintaining a feel for the transcendent, defined as the artists in question take it).

He explains, “Significant to many musicians’ understanding of jazz’s religiosity or spirituality is the experience of transformed perceptual or emotional states.” These states can be achieved through music, meditation, or other mystical paths. Of course, emotional states can be transformed by events other than the religious (drugs, losing oneself in a crowd activity, etc.). At times when Bivins asks, “But is it ‘religion’?” or “Is it jazz? Is it religion?” it’s easy to answer, “No, it’s not religion.” That quick response sets up the very limits that Bivins wants to question. The book doesn’t necessarily affirm that everything presented here is religion per se; Bivins says he’s chasing down “resonances” or “echoes”. It’s the corner glimpses that have meaning here, that lead to spirits rejoicing in and through jazz.

The catch is that Bivins succeeds admirably in his goal of starting a conversation, but in limiting himself to that objective, he has the advantage of playing in a field with no limits. While he deliberately leaves the conversation open, it would have been useful to start defining some of the terms. He describes historical works like Wynton Marsalis’s Blood on the Fields and From the Plantation to the Penitentiary as “historic modes” that “reveal what ‘religion’ might be” and that they represent religion. While an accurate analysis, it’s hard to see that as a practice or experience of religion any more than reading a systematic theology would count as prayer. If, as Bivins writes, “’religion’ blurs and drifts away”, it would be worth defining religion more directly in order to see the blur and drift, and to exclude the non-religious in the conversation.

Moving down this line, we eventually reach a point where the division between jazz and religion becomes indistinct. Bivins writes, “The capaciousness and abstraction by which jazz is named as religious is no evasion of the particulars of history – communities established or rituals undertaken – but a means by which religion’s surplus and volatility are announced, which serves also as the means by which listeners might understand their immersion in it” (emphasis in the original). If religion – spirits rejoicing – comes from something uncontainable and inexpressible verbally, jazz is a manifestation of that. The inarticulateness “does not stand watch, keeping us from understanding religious experience; it is at least part of the substance of that experience.” The fluidity of experience and the ungraspable center of experience are not the difficulties of defining religion or jazz or their combination, but those issues are part of what we should consider in our approach to musics or religions.

In this way, and in all these various experiences, we see jazz not just inspired by religion or replacing religion, but functioning (almost?) as religion, or at least in what Bivins refers to as “religion’s haziness”. He writes of the music produced in this plural tradition that “it also is what we say it is about: the sense, the reach, the acceptance of falling short, and the holy conviction to move forward, head turned up to the heavens” (emphasis in the original). Given the century of jazz and religion intersecting, it’s past time that we had this sort of questioning look into these spiritual entanglements, and Bivins nails what can’t quite be nailed down.