As I write this, a new, hopefully, progressive mayor, Brandon Johnson, has just been elected in Chicago, where I live. For many, a shift is in the air, and the time is ripe for doing and moving beyond what singer-songwriter Tracy Chapman called “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution“.

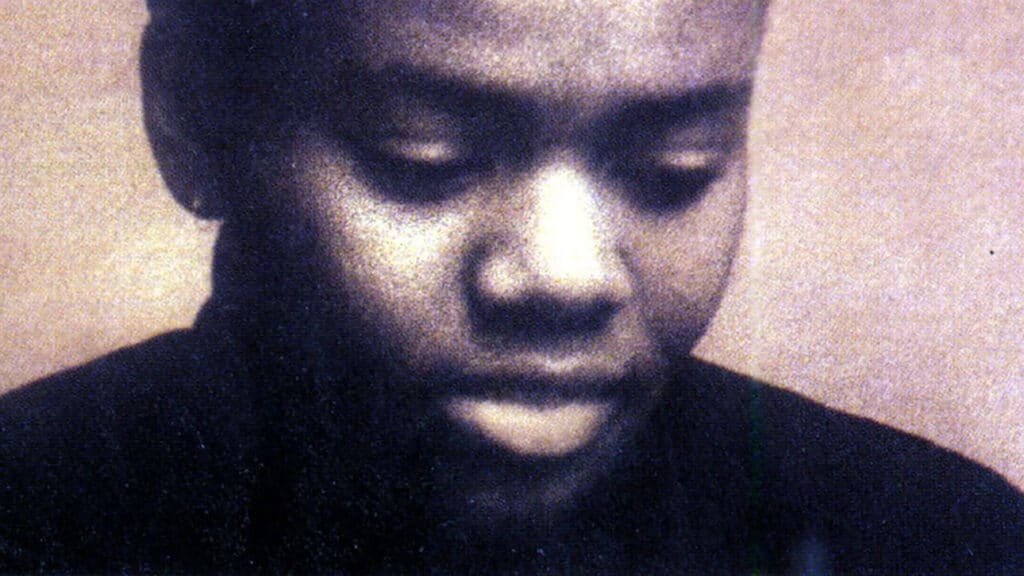

Thirty-five years after its release, Chapman’s self-titled debut album may be more important than ever. With environmental degradation, racist police brutality, poverty, gun violence, and other crises that Chapman sang about persisting, more people are ready for real structural change. Like sociopolitical statements in blues, jazz, gospel, soul, pop, and hip hop, Tracy Chapman met its moment forcefully. Chapman’s music was overtly political, introspective, and fiercely her own, and in an age of artificial gloss, it managed to appeal to mass audiences.

But beyond the towering “Fast Car“, covered by everyone from Xiu Xiu to Justin Bieber to Black Pumas to Luke Combs, most songs on Tracy Chapman have been forgotten. That’s a shame because the album is one of the great singer-songwriter albums in any decade or genre, a masterpiece whose impact continues to grow with succeeding generations.

However, the sociopolitical legacy of the record remains in question: even if Chapman’s message was revolutionary, were the social uses to which the album was put revolutionary as well? Despite Chapman’s involvement in concerts for Amnesty International and anti-apartheid causes, the answer then was no, but the album can still inspire a revolution now.

The album’s story is familiar to many Chapman fans: raised by a single mother in Cleveland, Ohio, and a graduate of the prestigious Tufts University, Chapman played at coffeehouses and landed a record deal with Elektra Records, and in April 1988, she released her debut to minimal hype or fanfare. After Chapman performed “Fast Car” at Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday celebration, the song became a Billboard top ten hit in the US, with the record reportedly selling over 20 million copies worldwide.

Tracy Chapman‘s smash success seemed unlikely. As a Black woman singing acoustic guitar-based rock and folk, she stood out from the 1980s pop scene, known for synthesizers, big hair, and makeup obscuring, for some, the music’s substance. As Chapman was later called the Anti-Material Girl by writer Ian Aldrich, the contrast between Chapman and such stars as Madonna could not have been more marked (Heather E. Harris, “What’s Class Got to Do with It? Facets of Tracy Chapman through Song”, The 1980s: A Critical and Transitional Decade, ed. Kimberly R. Moffitt and Duncan A. Campbell, Lexington Books, 2011).

In the years following Tracy Chapman, Chapman’s star faded, though she had a significant resurgence with her 1995 record New Beginning and the single “Give Me One Reason“. She has not released an album since 2008, making rare appearances on television for David Letterman and Seth Meyers, where she performed her debut’s opening track, “Talkin'” Bout a Revolution”, on the eve of the 2020 US presidential election.

So, for many, her debut cast a shadow over her career. “Fast Car” is considered a classic, one of the greatest story songs in popular music, and in 2021 Rolling Stone ranked it in the top 100 on their list of the greatest songs of all time.

Listening to Tracy Chapman reveals optimism about change and realism about the everyday struggles of people trapped in poverty and other systemic forces. “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution” rings hopeful about the possibility of real, tangible structural change, with a reverberant 12-string acoustic guitar and Chapman’s arresting rich contralto. Musician Billy Bragg chastised Chapman for the vagueness of the song’s lyrics—what, if anything, was Chapman singing about the methods to accomplish a revolution? (Gareth Thompson in 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die, ed. Robert Dimery, Universe Books, 2005)—but the song is an immediate standout on an album filled with brilliant songwriting and performances.

After such a message about revolution, “Fast Car” appears like it could undermine the message that change is possible. The song’s narrator begins as wide-eyed and naive, with Chapman singing that the car could enable “a ticket to anywhere”. But after a move, the narrator deals with the same issues as in her hometown: alcoholism, poverty, and disillusionment. So, the narrative in “Fast Car” illustrates the cycle of generational inequality and inequity under capitalism.

Although Tracy Chapman is not a concept album, there is a thread throughout about the need for change. “Fast Car” could be read as reflecting the futility of change. Still, in her lyrics, Chapman subtly critiques systems of inequity and inequality that reinforce stasis and pain, as scholar Heather E. Harris writes in her essay, “What’s Class Got to Do with It? Facets of Tracy Chapman through Song.” With 35 years of distance, it could seem like the song is an allegory for the album’s legacy: Tracy Chapman didn’t lead to a revolution, so it could be argued that real change is impossible.

Critic Tom Moon wrote in 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die (Workman Publishing, 2008) that “‘Fast Car’ belongs alongside ‘We Gotta Get Out of This Place’ and ‘Born to Run’ on the short list of great escape songs.” Whatever tracks others consider all-time escape songs and records–I would add country tracks like Jo Dee Messina’s “Heads Carolina, Tails California”, for one– “Fast Car” is atypical among them in providing a complete story before and after the longing for escape takes hold.

“Across the Lines” focuses on racialized violence, including the intersectionality of violence against Black girls: the lines, “Little Black girl gets assaulted, no one knows her name / Lots of people hurt and angry, she’s the one to blame” relate to how Black girls and women are differently targeted and forgotten in cases of sexual violence, as feminist scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw has written about in such articles as “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.”

In recent years, Crenshaw’s TED talk and other work have highlighted the continuing importance of intersectionality regarding police violence, media coverage, and social movements. In some ways, Chapman was a pioneer in bringing these issues into mainstream discourses, regardless of her expectations for the album’s success.

“Behind the Wall” continues the theme of gender violence with a chilling a cappella solo performance. The track is stark and disturbing, and its lyrics about the unhelpfulness of the police still resonate today. “Baby Can I Hold You“, one of Chapman’s best-known tracks, is simple and affecting, full of tension between love and remorse.

The next two songs utilize Caribbean musical forms to highlight musical continuities between forms and themes in the African diaspora. “Mountains O’ Things” uses Hi-life music (Jenkins 347), and “She’s Got Her Ticket” has a reggae beat. As Jenkins highlights, both songs engage themes of fight and flight that appear throughout the album.

“Mountains” mocks consumerism while the narrator longs for the ability to consume more out of necessity, which could function as a critique of capitalism and its effects. “Ticket” sounds optimistic about the possibility of change, which could serve as the opposite of “Fast Car” in symbolizing the album’s sense of hope.

In “Why?“, Chapman dares to point out the hypocrisy of business as usual around the world, asking critical but ostensibly futile questions. “For My Lover” illuminates the narrator’s disappointment, facing jail time for queer love. When Chapman sings, “Is this love worth the sacrifices I make?” there is a more personally felt sense of futility than in “Why?” Ultimately, the album’s more personal storytelling is more affecting—and perhaps more convincing—than the calls for radical change.

“If Not Now…” holds a dual meaning, with Chapman’s narrator asking for a commitment to love and social change. This song shows the importance of decisive action, and its message against neutrality is especially relevant today in any context. The closing “For You” is my favorite of the love songs on the album, a quiet solo acoustic performance with Chapman singing what sounds like an intimate confession of love.

After listening to Tracy Chapman, one would be forgiven for thinking it sounded retro and, therefore, irrelevant in its time—and more so now. In 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die, critic Gareth Thompson calls the album full of “nagging naivety”, and with the 1980s-style, reverb-heavy drum sound along with the folk influences, Tracy Chapman is inevitably a period piece.

In other ways, however, it is highly relevant today, both musically and socially. One of the most critical and unusual aspects of the album’s greatness is Chapman’s husky, androgynous voice. In Sasha Geffen’s book, Glitter Up the Dark: How Pop Music Broke the Binary (University of Texas Press, 2020), Geffen argues that Chapman was key in a vocal shift in popular music to using what they call “butch throat”. That startling instrument is one of the most powerful modes by which Chapman communicates her anger as well as her sense of intimacy. Clearly, Chapman’s music transgressed binary gender expectations.

In addition, Harris analyzes lyrical themes in Chapman’s debut–”Radical Change, Elusive Dreams, and Twisted Love”–as highlighting the problems of capitalism. Harris’ analysis brilliantly uncovers issues absent from most discussions of Chapman’s music.

In a 2022 journal article, folklorist Rasheedah A. Jenkins writes of fight and flight as key themes in the album, which adds to Harris’s point if we consider what Chapman’s songs’ narrators are fighting and flying from poverty, destitution, and societal marginalization.

That marginalization, of course, is not only about class. A working-class, queer, and Black woman, Chapman writes about issues and systems affecting intersectional groups, including police brutality, domestic violence, and LGBTQIA+ issues. Though Chapman has never officially come out, novelist Alice Walker later spoke of dating her, and the theme of queer love, again, surfaces in “For My Lover”.

For many, the album’s tremendous promise went undelivered politically, artistically, and, to a lesser extent, commercially. Politically, the album did not lead to immediate change, though singer-songwriters like Chapman and Suzanne Vega led a resurgence of female singer-songwriters into the 1990s.

Harris goes further by arguing that despite the “appear[ance] that Chapman presents counter-hegemonic messages to the opulence ideology of the time, her messages actually served as a safe and soothing balm for both consumers and capitalists of the time” and that “they were used by the sustainers of the dominant ideology as a tool to quell what could have been a real threat to status quo and the 1987 stock market crashes. Through her music, the ire and frustration of the various populations could be calmed by way of lyrics and rhythms rather than expressed in society itself in the form of protests and demands for fundamental change to structures of various societies that maintain the ‘class quo’.”

While it seems unfair to expect popular music to cause societal shifts, there is much merit to Harris’s points. At the time, there was hope that Chapman’s music could have led to greater change, and perhaps if her music had sustained the same level of public attention and critical acclaim in subsequent years, regardless of its quality or amount of overtly political lyrics, more could have been accomplished in the service of mass liberation.

I’ve never read a review of Chapman’s discography that did not rate her debut as her best album by far, but that shouldn’t obscure the work she has created since. Songs like “At This Point in My Life“, “Paper and Ink“, “Tell It Like It Is “, and “Change” are gems that deserve far more of an audience.

However, music, art, and popular culture can mobilize people for mass action to demand and institutionalize change. Such cultural texts do not have to be as aggressive as that of Rage Against the Machine or Public Enemy to spread a message of resistance and revolution.

In her 1992 essay “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance”, the late Black feminist cultural critic bell hooks questioned the utility of rhetoric without mass action when she wrote, “Who can take seriously Public Enemy’s insistence that the dominated and their allies’ fight the power’ when that declaration is in no way linked to a collective organized struggle” (Black Looks: Race and Representation, South End Press, 1992). Theoretically, the same could be argued of Chapman, as Harris argues that Chapman’s music challenged and reinforced capitalists’ power.

I would argue that Chapman’s music and message were revolutionary, even if their long-term impact is easy to minimize—though hopefully in flux. The spark of revolution from past eras hasn’t died, although the dominant political culture in the US might convince us otherwise.

In his 1975 journal article, “Black Theology on Revolution, Violence, and Reconciliation”, the late theologian James H. Cone argued that revolution means “a sudden, radical, and complete change; or as Jürgen Moltmann puts it: ‘a transformation in the foundations of a system—whether of economics, of politics, or morality, or of religion'” (collected in Risks of Faith: The Emergence of a Black Theology of Liberation, 1968-1998, Beacon Press, 1998). Cone believed revolution could only happen on the terms of the oppressed within a system.

Today’s world needs a revolution. Despite the fearful white backlash against diversity initiatives and what is labeled Critical Race Theory, diversity, like integration, doesn’t fundamentally change anything in society. If Tracy Chapman teaches us anything, it’s that we need fundamental change to reckon with the issues she writes about.

Tracy Chapman can still inspire action, including protests and questioning complacency to act, as much as the record may have reinforced that complacency in its time. With hindsight, it becomes apparent that it is up to all of us to take sides and learn from the messages of musicians and creators like Tracy Chapman.

If the revolution surrounding Tracy Chapman’s music has never materialized, as suspicious as I have been in the past of abolitionism regarding capitalism, whiteness and white supremacy, and cis-heteropatriarchy, I firmly believe a revolution can happen. Simply “talkin’ bout” it may not cause a seismic shift in systems or consciousness, but I sure hope we heed Chapman’s call before the interests of the elite and powerful consume us all.