“All the world is a stage.” Some Brit said that. Typical of a Brit, I suppose. Strikes one as witty without necessarily being so. Still, it makes you think. I suppose it is intended to make you imagine that we are always playing roles, that there is no true identity, only a series of personae that we portray in order to make our way through our existences. Bollocks! There is a more interesting take on this truism, and it is precisely the take that another Brit developed into what might approximate the calling card of his career.

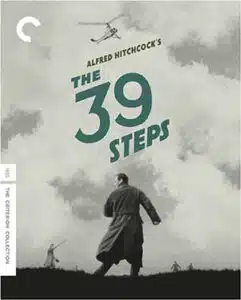

That second Brit, of course, was Alfred Hitchcock. (The first Brit doesn’t really merit mention, does he?) That calling card snapped into focus with Hitchcock’s amazing British thriller (that is, a film made before his arrival in the United States), The 39 Steps. This film inaugurated the basic schema that we continue to associate with Hitchcock—the classic “wrong man” scenario.

For Hitchcock, unlike that earlier Brit, all the world is a stage not because we are always acting but rather because it seems that so often someone else has written our scripts for us, and we are forced to adapt to situations, not of our own making. And so we find ourselves (not unlike some scholars who imagine Shakespeare’s cohorts found themselves) improvising around a plot structure over which we have no real control—the efficacy of the individual agent resides only in the moment-to-moment actions that arise from a pragmatic response to contingency.

And here it is, the film that started it all. There would be, perhaps, no Man Who Knew Too Much, no North by Northwest, no Strangers on a Train without The 39 Steps. In this film, we meet Richard Hannay (played by the exceedingly dapper Robert Donat), a Canadian visiting London on business. He encounters a beautiful and exotic woman in distress (Annabella Smith) at a music hall just after gunshots cause a stampede toward the exits.

As it turns out, she fired the shots. Nonetheless, Hannay takes her home (well, who can blame him?) and feeds her haddock. It seems she is a spy working for god knows whom, but she is attempting to stop the transmission to foreign agents of information vital to British safety. She wants to go to Scotland. But she dies with a knife stuck in her back. A bit of bad luck, that. We never find out why someone would break into Hannay’s apartment and kill Annabella but not kill Hannay. Sporting fun, I suppose.

Anyway, Hannay is on the hook, so to speak. He flees. He thinks of turning himself in, but then he hears a police officer say that he doesn’t stand a chance, so he continues fleeing. No one believes him, not even the beautiful stranger (Pamela, played by Madeleine Carroll) he meets on a train to Scotland. (You knew he would go to Scotland, didn’t you?) So he runs.

Why, you ask? What else can he do? It isn’t logical, nor is it meant to be. The script written for this poor fool is patently absurd. No matter. He didn’t choose it, and he cannot alter it. That is the entire point of the Hitchcock premise. The individual fellow doesn’t write the rules, and he doesn’t entirely obey the rules (or else he would wind up dead within the opening scenes of The 39 Steps). Rather, the individual tries to maneuver around the game’s structure as best he can. No choice, really.

The amazing thing about Hannay, which should strike one as preposterous, is the surreal sangfroid exhibited by our beleaguered hero. He is shot by his main adversary (the head of the mysterious 39 Steps organization), only to be saved by a pilfered hymnal. Does he freak out? No. He steals his would-be assassin’s car to drive to the local police station.

The police seem to be on the take, so he jumps out the window and blends in with a parade. Dodging into a local assembly hall, he delivers himself of a brilliant political speech (a remarkable feat of improvised rhetoric) without once allowing his demeanor to register the slightest trace of doubt or confusion. No matter what the circumstance, Hannay moves forward.

He is arrested (along with Pamela, who is told she must serve as a witness), but even when he realizes his captors are not police officers but rather members of the spy organization, he never loses his cool. He escapes (with Pamela in tow) and continues on. It is this aspect of the Hitchcock “wrong man” scenario that so intrigues me. It doesn’t matter if the entire world goes topsy-turvy as long as you keep your head. If you remain calm, cool, and collected, you will prevail—you will also manage to impart your fair share of witticisms and wind up romantically linked to an unimaginably beautiful blonde. Nice deal, that!

This is ultimately what I find so fascinating and satisfying about the “wrong man” scenario. Life is not a tale told by an idiot full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. Well, it is full of sound and fury and signifies nothing. But the idiot is the writer, the bizarre scenographer who wants to temper Shakespeare with Samuel Beckett. The character, the individual, makes do. He tells the tale, but he bends its structure just enough to escape the shackles set forth for him by the malevolent, if somewhat humorous, author—whomever that might be.