Did George W. Bush, the 43rd President of the United States, preside over a nation motivated by fear, or was he an agent of fear? Many critics and social historians would opt for the latter, citing a long list of actions taken by the Bush administration that were packaged in bunting laced with fear: Osama Bin Laden, the terror mastermind behind 9/11, was hiding in Afghanistan so combat troops were needed to ferret him out and oust the theocratic Taliban from power in the process. Meanwhile, Saddam Hussein, a supporter of worldwide terror, was engaging in ethnic cleansing in Iraq and stockpiling weapons of mass destruction; once again, it was imperative to throw tanks and guns and troops at the problem.

“Shock and awe” it was called, from the military doctrine authored by Harlan K. Ullman and James P. Wade, the use of overwhelming power, dominant battlefield awareness, dominant maneuvers and spectacular displays of force to scare the living crap out of the enemy and destroy their willingness to fight. In a word: fear.

More recently, when the bubble finally burst on the so-called “ownership society”, George W. Bush and his Federal Reserve and US Treasury stooges urgently pushed for a multi-billion dollar bailout of ailing US financial institutions to avoid wide scale bank failures, even more home foreclosures, the dissolution of Social Security and Medicare, a return to bread and soup lines and, presumably, riots in the streets, martial law, and the inevitable reunion of Tony Orlando and Dawn to soothe our frayed nerves.

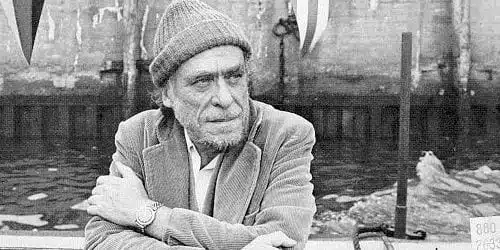

On the surface of it, all of the above may seem like dark Karl Rove-inspired fear mongering to provoke a desired response but fear, one must understand, is the lubricant that keeps the wheels of human progress greased. Charles Bukowski understood this concept all too well.

In 1944, at the age of 24, young Bukowski found himself far from his beloved Los Angeles. His aimless wanderings from one common labor job to another (humorously chronicled in the 1975 novel Factotum) took the aspiring writer to New York City where he “found a job, reluctantly, as a stock boy or something for a distributing house of magazines and books.” When the foreman discovered that his new hire had been published in the latest issue of Whit Burnett’s acclaimed fiction anthology, Story, Bukowski was immediately promoted to foreman.

“I wasn’t a very good foreman,” Bukowski recalls in the 1971 essay Dirty Old Man Confesses. “I’d come in drunk and goose the workers with hammer handles while they were nailing their crates shut. But they liked me. Which was wrong – a good foreman is a man you fear. The entire world functions on fear.”

Dirty Old Man Confesses is one of 36 previously uncollected works from perhaps the most infamous and provocative American writer of the 20th century. Many of the stories and essays collected in Portions from a Wine-Stained Notebook, masterfully curated and edited by David Stephen Calonne, seem designed to counteract the public myth of Bukowski as a drunken, hedonistic, marginally talented Bard of the dispossessed who despised the 9 to 5 ethos (he condemned it as “toil without meaning”) and to underscore the writer’s contempt toward a culture that “will admire a man for his way of life rather than what he produces.”

“I have created the eternal drunk image somewhere in my work,” Bukowski laments in Notes of a Dirty Old Man, “and there is a minor reality behind it. Yet, I feel that my work has said other things. But only the eternal drunk seems to come through.”

In Portions from a Wine-Stained Notebook, the most important contribution to Bukowski studies to date, the image of the eternal drunk may not be exactly laid to rest, but a new blood-swollen, multi-dimensional creature arises from these pages. It’s a sensitive, tortured, “vulnerable man of genius trapped in a small room with a typewriter”, a fiery provocateur for social change, a profoundly serious producer and defender of poetry, a passionate spokesman for “the defeated but still hopeful” dwelling in the lower depths of America (though he would never claim to speak for anyone but himself), an intense lover of classical music and the possessed madmen who created it, and a keen-eyed, hard-bitten naturalist essaying the hardscrabble existence of a writer (“The life of a writer is unbearable … starving writers live worse than skid row bums”) and the harsh desperation of life on the margins of Los Angeles.

Bukowski believed that pride “has no right in things upright and mechanical”, that primal feeling trumped intellect in any race of the body or mind, and that a thousand scarlet sunsets bleeding into the Pacific Ocean were no match for a woman’s beauty. But beauty, Bukowski instructs, “would not be beautiful without flaws.”

Stigmata and Mozart

“Bukowski’s art is dedicated to revealing his own bloody stigmata,” writes Stephen Calonne in the scholarly introduction to Portions, “to dramatizing himself (often humorously) as sacrificial victim in simple, direct, raw hammered language free of pretense and affectation.”

Henry Charles Bukowski’s troubled upbringing, his “bloody stigmata”, is memorably captured in the fan favorite novel Ham on Rye (1982), but the traumas of his youth remained a subject of constant angry and bewildered reflection in a great deal of his poems, fiction, and personal musings, represented in this outstanding collection in at least four essays. From Dirty Old Man Confesses (October 1971):

I was born a bastard – that is, out of wedlock – in Andernach, Germany, August 16, 1920. My father was an American soldier with the army of occupation; my mother was a dumb German wench. I was brought to the United States at the age of two – Baltimore first, then Los Angeles, where most of my youth was wasted and where I live today.

My father was a brutal and cowardly man who continually whipped me with a razor strap for the slightest reasons, often invented. My mother was in sympathy with his treatment of me. “Children should be seen and not heard” was my father’s favorite expression … I never spoke except to say yes or no. After the age of five or six, I stopped crying when I was beaten. I hated the man so much that my only revenge upon him was not to cry, which made him beat me harder. The tears would come but they were silent tears. The beatings were always in the bathroom – I guess because the razor strap was there. And when he was finished he would say, “Go to your room.”

I was in the Underground early.

Young Bukowski grew to be a six foot tall man, and other monsters would replac his father. After maturity he “bummed the country at random, back and forth, up and down, in and out”, briefly attending Los Angeles City College to study Journalism and English, and losing his virginity at the age of 23 to a woman he described as “a 300 pound whore”.

Exempted from service in World War II for “Failing to Meet Medical Standards” after a physical and psychological evaluation, Bukowski roamed about the country, working in the Southern Pacific Railroad yards, tool warehouses, department stores, various janitorial and grunt jobs, but he always returned to Los Angeles, “living in a falling down court just off the poor man’s Sunset Strip” for many long, despairing years:

There is a whole section of people down there who live on air and hope and empty returnable bottles and the grace of their brothers and sisters. They live in small rooms, always behind in the rent, dreaming of the next bottle of wine, the next free drink in the bar. They starve, go mad, are murdered and mutilated. Until you live and drink among these you will never know the abandoned people of America. They are abandoned and they have abandoned themselves.” — “The L.A. Scene”

In March 1952, Charles “Hank” Bukowski was accepted as an Indefinite Substitute Carrier for the United States Postal Service in Los Angeles; he was promoted to Distribution Clerk in March 1959, a position he would hold until January 1970. During all that time, the war years and the post-war prosperity, Bukowski had been writing, writing, writing, a scribe in search of a voice. After the 1944 publication of “Aftermath of a Rejection Slip” in Story (the same published effort that resulted in his promotion from stock boy to foreman, reproduced in Portions), he sold the dark and brooding short story ”20 Tanks From Kasseldown” to Portfolio III in 1946 (also included in this collection) and his first series of poems were published in Matrix the same year.

Legend has it that after the sale of “20 Tanks” to Portfolio in 1946, Bukowski stopped writing for ten years, a myth promoted by the author himself in interviews and reinforced on the dust jacket to The Most Beautiful Woman in Town and Other Stories (City Lights Publishers, 2001). Well, legends and bibliographies must now be revised because one of the previously uncollected treasures in this collection is a stirring short story, “Hard Without Music”, a tale of a typical Bukowski down-and-outer named Larry (he had yet to create his “Hank Chinaski” alter-ego) who is forced to sell his vast collection of classical music recordings to two nuns. Larry, “feeling suddenly old and worldly” is compelled to share with the nuns what the music means to him:

Good music crept up on me. I don’t know how. But suddenly, there it was, and I was a young man in San Francisco spending whatever money I could get feeding symphonies to the hungry inside’s of my landlady’s wooden, man-high victrola. I think those were the nest days of them all, being very young and seeing the Golden Gate Bridge from my window. Almost every day I discovered a new symphony … I selected my albums pretty much by chance, being too nervous and uncomfortable to understand them in the glass partitions of the somehow clinical music shops … There are moments, I have found, when a piece, after previous listenings that were sterile and dry … I have found that a moment comes when the piece at last unfolds itself fully to the mind. – Hard Without Music”

“Hard Without Music” was published in a special Spring-Summer issue of Matrix in 1948 and the early appearance of this previously uncollected work of fiction probably represents the very first of many Bukowski pieces to come that would dwell on his love of classical music. Editor Calonne notes: “Bukowski composed a wide array of poems which are either direct homages to great composers or make references to their lives and works including Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner, Chopin, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Schumann, Sibelius, Stravinsky, Vivaldi, and Wagner.”

A New Poetic Concept Born of Blood

In 1955, at the age of 35, Bukowski was rushed to the charity ward of the Los Angeles County hospital, hemorrhaging at the bright red climax to a ten-year drinking bout. He was “dying, hemorrhaging out of my mouth and ass continually … all that cheap wine and hard living coming through and out – fountains of blood.”

Bukowski’s experience in the cold-hearted, bureaucratic charity ward, the dumping ground for the Underground, would inexorably begin the alteration of his life’s path, if indeed it can be said that he was following a well-charted path to begin with. Observing the walking wounded in the hospital, Calonne explains, drawing on Bukowski’s own account in “Life and Death in the Charity Ward” from The Most Beautiful Woman in Town, imbued him with the burning question of “why the official, safe, Establishment literature of the ages had so often been silent about those in the most pain: the victimized, the poor, the mad, the unemployed, the skid row bums, the alcoholics, the misfits, the abused children, the working class. His poetic world, like Samuel Beckett’s, (would become) the world of the dispossessed, ‘the thin, proud, dying,’ and he defined himself as a poetic outlaw; there can be no safety in a life lived in extremis at the edges of madness and death.”

After receiving 13 pints of blood and glucose at the charity ward, Bukowski embarked on a new life: “I found a place on Kingsley Drive, got a job driving a truck and bought an old typewriter. And each night after work I’d get drunk. I wouldn’t eat, just knock out eight or ten poems … I was writing poems but I didn’t know why.”

The market Bukowski focused on was the newly-emerging “little magazines”, which he considered “a much finer stomping ground for the little bit of good and realistic writing” that was being done.

I wrote more poems, changed jobs and women … and then they began to pick up on me. Little chapbooks of poems appeared: Flower, Fist and Bestial Wail, Run with the Hunted, Pomes for Broken Players. My style was very simple and I said whatever I wanted to. The books sold out right away. I was understood by Kansas City whores and Harvard professors. Who knows more? … I was the new poetic concept – far from the educated and careful poesy – I laid it down raw. Some hated it, others loved it. I couldn’t be bothered. I just drank more and wrote more poems. My typewriter was my machine gun and it was loaded. — “Dirty Old Man Confesses”

With the exception of the title piece, which is a unique hybrid of journalism and poetic verse, Portions from a Wine-Stained Notebook does not contain any previously uncollected poetry. There is, however, an ample abundance of essays on the topic of poetry, a subject that Bukowski could orate upon with the fire and epic pomposity of a Southern Baptist minister on Sunday morning.

“It’s like the old weather gag,” Bukowski writes in “A Rambling Essay on Poetics and the Bleeding Life Written While Drinking a Six Pack (Tall)”, “everybody talks about poetry but nobody can do anything about it.”

Many American readers, schooled in traditional form, have great trouble with Bukowski’s almost formless poetry (“prose with line breaks” is the most commonly-heard complaint), despite the fact that there are over 40 volumes of his poems available in the market, which means, by most reasonable standards, that the old man must have been doing something right. After all, Kellogg’s would cease production of Corn Flakes if consumers stopped placing the hearty cereal on their breakfast tables and Ecco (an imprint of publishing conglomerate Harper Collins) would’ve long ago ceased publication of books like Pleasures of the Damned: Poems, 1951-1993 if there wasn’t an audience hungry for the product.

In the 1966 essay “In Defense of A Certain Type of Poetry, A Certain Type of Life, A Certain Type of Blood-Filled Creature Who Will Someday Die”, Bukowski railed against Establishment poetry for “talking about useless things with great subtlety. A dirty dull little game. Most of our bad and acceptable poetry is written by English professors of state-supported, rich-supported, industry-supported universities.”

It was the gatekeepers, “the artistically intelligent who have fallen into money and position”, that the poet most resented. Bukowski believed that poetry, to remain true and pure, had to be freed from shackles and restraints, like other art forms that constantly evolve (painting and architecture immediately spring to mind). It was the common man, he proselytized, who was capable of creating the most honest poetry: “Our days in the jails and madhouses and flophouses have let us know more (about) where the sun comes up than from than any workable knowledge of Shakespeare, Keats, Shelley.”

In the title essay, Bukowski ponders further with a fair measure of self-deprecation: “When I have a poem accepted by a magazine that prints so-called quality poetry, I ask myself where I have failed. Poetry must continually move out of itself, away from shadows and reflections. The reason so much bad poetry is written is that it is written as poetry instead of concept. And the reason the public doesn’t understand poetry is that there is nothing to understand, and the reason that most poets write it is that they think they understand. Nothing is to be understood or ‘regained’. It is simply to be written. By someone. Sometime. And not too often.”

The Strange and Terrible Saga

What makes Portions from a Wine-Stained Notebook tower over other critical studies of Bukowski is editor Calonne’s sturdy emphasis on the author’s long-overlooked and undervalued work as an essayist.

“I wasn’t even a revolutionary,” Bukowski writes, “but I knew how a true revolutionary should think.”

Author: Charles Bukowski

Book: The Pleasures of the Damned

Subtitle: Poems, 1951-1993

US publication date: 2007-10

Publisher: Ecco

Contributors: John Martin (Editor)

Formats: Hardcover

ISBN: 9780061228438

Image: http://images.popmatters.com/book_cover_art/b/bukowski-pleasuresdamned.jpg

Length: 576

Price: $29.95

Author: Charles Bukowski

Book: Love Is a Dog from Hell

Subtitle: Poems, 1974-1977

US publication date: 2002-06

Publisher: HarperCollins

Formats: Paperback

ISBN: 9780876853627

Image: http://images.popmatters.com/book_cover_art/b/bukowski-dogfromhell.jpg

Length: 312

Price: $16.00

Author: Charles Bukowski

Book: The Pleasures of the Damned

Subtitle: Poems, 1951-1993

US publication date: 2007-10

Publisher: Ecco

Contributors: John Martin (Editor)

Formats: Hardcover

ISBN: 9780061228438

Image: http://images.popmatters.com/book_cover_art/b/bukowski-pleasuresdamned.jpg

Length: 576

Price: $29.95

Author: Charles Bukowski

Book: Love Is a Dog from Hell

Subtitle: Poems, 1974-1977

US publication date: 2002-06

Publisher: HarperCollins

Formats: Paperback

ISBN: 9780876853627

Image: http://images.popmatters.com/book_cover_art/b/bukowski-dogfromhell.jpg

Length: 312

Price: $16.00

Author: Charles Bukowski

Book: Pulp

US publication date: 1994-03

Publisher: HarperCollins

Formats: Paperback

ISBN: 9780876859261

Image: http://images.popmatters.com/book_cover_art/b/bukowski-pulp.png

Length: 208

Price: $15.00

Author: Charles Bukowski

Book: Pulp

US publication date: 1994-03

Publisher: HarperCollins

Formats: Paperback

ISBN: 9780876859261

Image: http://images.popmatters.com/book_cover_art/b/bukowski-pulp.png

Length: 208

Price: $15.00

The sometimes-unreliable guardians of popular culture in America would have us believe that the late John Lennon represents the apex of progressive and revolutionary thought in the turbulent tide of cultural change represented by the ’60s. Funny what an assassin’s bullet can do to one’s standing and significance on the cultural pendulum. Lennon and the Beatles embraced (and in many ways advanced) the drug and hippie culture that flourished in the ’60s. But Bukowski was right there in the thick of it, too, a 47-year-old man “arriving at full middle age” when the Summer of Love announced itself in 1967.

Not unlike Hunter S. Thompson, who derided the new counterculture in 1967 for lacking the political convictions of the New Left and the artistic soul that the Beats sought to instill in the fabric of American society, Bukowski looked around at the strange and terrible saga unfolding before him and recognized the great cultural shift that “the dead masses” failed to acknowledge … the American Dream had died. Only now, eight years into the new millennium, can we fully appreciate the many eulogies Bukowski wrote under the guise of his Notes of a Dirty Old Man columns for the Open City weekly and other underground and counterculture publications.

To lead the dead mass our so-called leaders have had to speak dead words and preach dead ways (and war is one of their ways) in order to be heard by dead minds. History, because it is built in this beehive fashion, has left us nothing but blood and torture and waste – even now after 2,000 years of semi-Christian culture the streets are full of drunks and poor and starving, the murderers and police and the crippled lonely, and the newly-born shoved right into the center of the remaining shit – Society. (1966)

John Updike echoed Bukowski’s sentiment in Rabbit is Rich (1981): “The world keeps ending but people too dumb to know it keep showing up as if the fun just started.”

As David Calonne points out in his introductory words, “the underground publications to which Bukowski contributed his stories and essays began to proliferate during the Sixties and it was then that his creativity detonated in multiple directions.”

Bukowski’s Notes of a Dirty Old Man column debuted in Open City weekly in May 1967 and ran for 87 weeks. The column, which expanded Bukowski’s reputation beyond Los Angeles and the small press universe, appeared variously in the L.A. Free Press, Berkeley Tribe, Nola Express, the National Underground Review, and the New York Review of Sex and Politics. Five of Bukowski’s priceless Dirty Old Man columns are collected in Portions, including the first installment offering the author’s somewhat dubious suggestions for dealing with drunk drivers, the overreaching point being a mistrust of authority and the imposition of morality upon the masses by legal instrument.

Like a mad prophet peering into the future, Bukowski railed against the credit-driven economy and the deadening effects of the nine-to-five lifestyle. Unbelievable as it may seem, Bukowski issued this chilling warning in 1970:

“At this time there are too many people afraid for their jobs, there are too many people buying cars, TV sets, homes, educations on credit. Credit and the eight hour day are great friends of the Establishment. If you must buy things, pay cash, and only buy things of value – no trinkets, no gimmicks. Everything you own must be able to fit inside one suitcase; then your mind might be free.”

Bukowski “realized that a man could work a lifetime and still remain poor”, his wages taken in mindless consumer spending that keeps the great economic beast of the free market alive and well.

Finally, in November 1969, aided by the financial assistance of John Martin of Black Sparrow Press (publisher of many of Bukowski’s now-classic novels and poetry collections), Bukowski “exited his long years of servitude at the Post Office” and opted out of the whole mess, embarking on his new life as a professional writer. From Notes on the Life on an Aged Poet (1972):

I had, since the age of 35, been writing poems and stories. I decided to die on my own battlefield. I sat down to my typewriter and I said, now I am a professional writer. Of course, it wasn’t simply that easy. When a man works for years at the same occupation, his time is another man’s time. I mean, even with an 8 hour day, that day is taken. Add travel time to and from work, plus work, plus eating, sleeping, bathing, buying clothes, automobiles, tires, batteries, paying taxes, copulating, having visitors, getting sick, having accidents, having insomnia, having to worry about laundry and theft and weather and all the other unmentionables, there ISN’T ANY TIME LEFT for the man himself. And, when overtime is called often some of these necessaries must be left out, even sleep, and, more often, copulation. What the fuck? And there are even 5 and one half day weeks, six day weeks, and on Sunday one is expected to go to church or visit the relatives, or both.

The man who said “The average man lives a life of quiet desperation”, said something partly true. But the job also soothes men, it gives them something to do. And it stops them from thinking. Men — and women — don’t like to think. For them the job is the perfect haven. They are told what to do and how to do it and when to do it. 98 percent of Americans over the age of 21 are working, walking dead. My body and my mind told me that within three months I would be one of them. I demurred.

His greatest fame lay ahead of him.

Like the equally brilliant Hunter S. Thompson, who lacked the intestinal fortitude to ride it out to the natural end, Bukowski knew that the whole goddamn ball of wax was a scheme, a hoax, life was a joke spent in service to cold machines and colder political and moral creeds that demanded a price far beyond their worth, with the ultimate punch line arriving at the end, yet he still managed to hang on for another 23 years before he was lowered into the cold, cold ground under a marker with two simple, cautionary words engraved in the stone: DON’T TRY.

The Hardest Work Imaginable

When Willy Vlautin was 20-years-old, young and impressionable, with success as a musician and novelist (The Motel Life, Northline) years ahead of him, he took a temporary job parking airplanes at the annual air show in his hometown of Reno, Nevada.

“Most of the day was spent sitting on a lawn chair, reading Bukowski books. The job lasted a week and every night when I’d get off work my cousin and I would go out and get drunk,” Vlautin tells PopMatters. “Now, we’d usually get drunk a couple of times a week but after reading Bukowski I didn’t feel guilty about drinking quite often so we went on a bender. It seemed like an easier way to get by, to just be drunk. The problem is I never saw any of the women that show up in his stories. I kept thinking they’d show up but they never did; the reality of it was, I simply got drunk and blew all my money.”

The last morning of the temp job at the air show, Vlautin recalls, he was suffering from a hangover so severe he could barely navigate the ground at his feet, let alone park an airplane.

“I was sitting in the lawn chair trying to keep it together and the sun was beating down mercilessly and right then I told myself that I couldn’t read any more Bukowski. He was a bad influence. I got off work, went back to my place, gathered up all my Bukowski books and went down to a book store and sold them, hoping that would clear up my head. A couple of weeks later, after my guilt let up, I realized that maybe I wasn’t cut out for being alright, that maybe Bukowski really did have the right idea. So I went to the used book store to buy my books back but the owner told me he had sold them the same day I brought them in.”

Vlautin’s tale, though colorful, is not unique; similar scenarios have played out in the lives of hundreds, if not thousands, of aspiring writers the world over. The demographic is usually the same: young men from troubled backgrounds and warring families, grappling with identity issues, out of control hormones, and a belief that the bottle is their best friend.

They find a kindred spirit in Bukowski but, frankly, they get the message all wrong. The sex and rampant debauchery in Bukowski’s six novels and countless short stories, the booze and broads and wicked depravity, was never meant to inspire or instruct; the author was simply meeting marketplace demands. In “Basic Training” (1991), Bukowski’s valedictory essay on the writing life for Portfolio magazine (the final chapter in Portions from a Wine-Stained Notebook), Hank writes:

Finally, after decades of small rooms, park benches, the worst of jobs, the worst of women, some of my writing began to seep through, mostly in the little magazines and the porno journals. I found the porno journals to be a great outlet: you could say anything you wanted, and the more direct, the better. Simplicity and freedom at last, between the slick photos of beaver shots.

Bukowski elaborated further in a 1993 interview with journalist and author Silvia Bizio, remarking: “The reason sex got into so much of my stories is because when I quit the post office, at the age of fifty, I had to make money. What I really wanted to do was write about something that interested me. But there were all those pornographic magazines on Melrose Avenue, and they had read my stuff in the Free Press, and they started asking me to send them something. So what I would do was write a good story, and then in the middle I had to throw in some gross act of sex … And I would throw some sex in it and keep writing the story. It was okay; I would mail the story and immediately get a three-hundred-dollar check.” (Bukowski’s fiction is well-represented in Portions by a slim handful of stories including the masterful Silver Christ of Santa Fe and The Night Nobody Believed I Was Allen Ginsberg, as well as the aforementioned Hard Without Music.)

Los Angeles Times journalist Christopher Goffard, author of the critically acclaimed novel Snitch Jacket, a darkly comic tale of human wreckage in the Southern California underworld of bikers, thieves, drug dealers, and police informants, offers his own opinion on the Bukowski lure and the allure of self-mythologizing that the author groomed like a prize poodle:

For me, all the boozing that seems central to Bukowski’s work was never the main thing – and it presents a hideous trap for every helpless manqué who thinks getting bombed will ever substitute for a fierce dedication to learning the craft. I think of Bukowski as the poet of lonely misfits and their desperation and the atmosphere that surrounds them, of people who are way past worrying about falling into the abyss: they’re there and they’re still alive and this is what it looks like.

Goffard, in a brief but pointed interview with PopMatters on the eve of the awards dinner for the Southern California Independent Booksellers Association (in which Snitch Jacket was nominated for Best Mystery Novel of the Year, sadly losing out to Joseph Wambaugh’s potboiler Hollywood Crows), sees Bukowski as a writer of dark comedy.

“He was an explorer of the absurd outer boundaries of quotidian loneliness and an indigenous L.A. despair. This is the world of sunlit desolation that shows up, over and over, in noir, though often without Bukowski’s humor or insight or ‘lived it’ advantage.”

L.A. noir novelist John Shannon’s Jack Liffey novels are peppered with Bukowski-styled random and utterly gratuitous oddities: naked men bellowing and hurling ice plant into traffic, amputees dueling with their prosthetic arms, crashed poultry trucks with burning chickens fleeing in all directions. Shannon tells PopMatters: “Since I’m working on a novel right now about the struggle between the homeless and those who are seeking to gentrify down on “The Nickel” – L.A.’s Skid Row – I return to Bukowski again and again because he knew so intimately the people who ‘live in small rooms, always behind in the rent, dreaming of the next bottle of wine.’

He had endless sympathy for the abandoned people of America and, in particular, the abandoned of Los Angeles, which he called ‘the only city in the world’ in one of his stories. When you read Bukowski, you have to allow time for the depth of his compassion for all the odd outcast people to settle within you. He was not a minor league Henry Miller as so many seem to think. He had a major league heart and was a wonderful, deeply observant poet, not just observant of the lost and lonely and tormented, but all of us.”

“A lot of people” recognized a Bukowski influence on the narrative style of Goffard’s Snitch Jacket when the book was initially released in September 2008.

“I haven’t read Bukowski religiously, but his work hit me at an impressionable time – when I was sixteen or seventeen, in particular the collection Love is a Dog from Hell,” Goffard says. “For me, he was like Kerouac and Henry Miller and Harlan Ellison, a writer who pulled back the curtain and let you watch him live and work and let you feel the sweat of an actual human being dripping onto the keyboard. These are the guys who helped demystify literature. It wasn’t written in castles in Europe by remote, unfathomable intelligences. The work was the man and the man was the work. Or so it seemed. This was long before I understood how powerfully self-perpetuating – and sometimes self-limiting – the creation of a persona can be and that in the end these writers’ greatest characters were themselves. But they gave you a creed, a stance, and they made the making of books seem holy, and this is intoxicating to a young writer.”

For Willy Vlautin, a chronicler of the underclass in his own novels, Bukowski has “always been a rough influence.”

“He puts so much romance in alcoholism and alcoholic women and bad jobs,” Vlautin says from his home outside Portland, Oregon. “Most people probably don’t think of it as romantic but in my head it is. When I read Bukowski I still end up going on some kind of bender hoping I can get to his world. He represents how I wish I could feel when I end up living like him, but unfortunately I end up living like a character in a Raymond Carver story: Depressed and beating the shit out of myself. I know Bukowski does the same but he does it with a different style. Bukowski lives at the bottom, whereas Carver is on the next floor above, losing everything, hanging by on a thread and hating himself the entire ride down. That’s more my style.”

In the end, it is perhaps best to allow Bukowski the last word from his last novel, Pulp, an L.A. noir parody written while undergoing and recovering from chemotherapy treatment for leukemia in 1993: “Most of the world was mad. And the part that wasn’t mad was angry. And the part that wasn’t mad or angry was just stupid. I had no chance. I had no choice. Just hang on and wait for the end. It was hard work. It was the hardest work imaginable.”