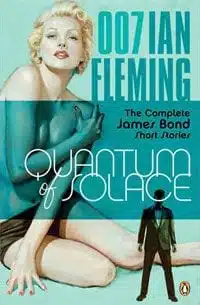

One can easily imagine that the US publication of the complete James Bond short stories by Ian Fleming will include a cover featuring the actor Daniel Craig, the latest to play the dapper super spy on the big screen.

The occasion of these stories’ re-issue, under the title Quantum of Solace: The Complete James Bond Short Stories, is undoubtedly this month’s release of the feature film of the same name, the 22nd Bond movie.

How disappointed readers are likely to be when they find that the title story of this collection is an excruciatingly boring monologue of steamy expatriate scandal in the Caribbean, in which Bond plays a peripheral role, if one can even call it that. If Quantum of Solace, the movie, takes any direction from the original story, then it will go down as the worst Bond flick ever (and considering A View to a Kill and License to Kill, that’s not an insignificant feat).

But of course, the movie simply borrows the name of the story, with all similarities ending there. In fact, all the recent Bond films save 2006’s Casino Royale have taken to borrowing their titles from the margins of Bond fiction, if at all (the 1995 film GoldenEye, featuring Pierce Bronson, was named after Fleming’s exclusive Jamaica retreat). And even the movies ostensibly made out of Fleming’s novels and short stories rarely hew to the original storylines.

And therein lies the problem when one considers James Bond, literary character. He doesn’t seem to belong to literature, and hasn’t, really, since Hollywood co-opted Fleming’s creation with 1962’s Dr. No.

All 12 of Fleming’s Bond novels have been filmed. Of the stories collected in Quantum — which previously appeared in For Your Eyes Only (1960) and Octopussy and the Living Daylights (1966) — five have been filmed, including “From a View to a Kill”, “For Your Eyes Only”, “Octopussy” and “The Living Daylights”.

Yet the other stories in Quantum have also figured into the Bond films, sometimes even providing the filmed storylines. It’s the story “Risico”, not “For Your Eyes Only”, that provides the plot for the eponymous film. “The Hildebrand Rarity”, a title Robert Ludlum probably has to thank for his entire career, provides the basic plot of the film License to Kill.

In some cases, the absolute disparity of plots between story and film is hard to understand. “For Your Eyes Only” is a perfectly respectable tale of revenge assassination in the Green Mountains of Vermont. Yet clearly the tale of “Risco” and its drug smugglers and high seas intrigue suggested a better movie, if perhaps the title didn’t.

To judge just the stories here, so little happens in many of them that it’s no surprise the films had to go in a different direction. “View to a Kill” centers on a rather obscure plot involving the murder of a dispatch rider for a NATO-like outfit outside Paris, instead of a plan to ruin Silicon Valley as in the film. “Octopussy” is another dull story about the WWII shooting of a spy in which Bond has perhaps five lines – a far cry from the movie’s use of India, priceless Faberge eggs and an island of sex goddesses.

And what of the women in these stories? Sadly, there are no Tiger Tanakas, Ursula Andresses, Kissy Suzukis or Pussy Galores in these pages. The names are Fleming’s, who had an unabashed perverted side, but these temptresses exist in the realm of the Bond novels.

Fleming’s novels were always more fully realized than his stories. His longer work provided ample room for plot and the development, if at times of the cardboard variety, of villains and love interests. It’s not that the stories here are rushed, but they more often than not do not create much room for anyone other than James Bond — and when they try, Bond is relegated to the weakest of supporting roles.

The stories that do this seem unnatural, almost like a betrayal: One wanted to read a bit about Bond’s thoughts on a proper evening’s drink, or the charms of Paris, and instead there is some British expat droning on about the latest scuttlebutt at Government House.

Fleming’s fiction exists for Bond to be front and center, and it is worth noting that Fleming’s accomplishment was to create one character in which there is not a single trait so minute as to escape attention. Hollywood jumped on Bond, though in the beginning not as enthusiastically as one might assume, because Fleming handed them a character fully formed. In essence, Bond was made for the big screen.

Which raises the question of whether there is any relevance to the Bond novels and stories, especially among readers whose only connection with the character is through the films.

To read the best of Fleming’s work is to be given not only a premonition of the restrictions of the Cold War, but a glimpse at the dying gasps of British colonialism, in which a country accustomed to ruling the world finds itself trying to carve out a new role. Beyond that historical element there is a certain value in considering what Fleming’s creation wrought for the pulp and espionage genre. There’s no Ludlum, Le Carre, Follett or Forsyth without Fleming.

But that’s speaking of the best of Fleming’s fiction, to which none of the stories in Quantum belong.