Late autumn remains the best time for ghost stories — and it’s not just the presence of Halloween that inspires a morbid fascination with death. I suspect our desire for a scary story has something to do with the light, or lack of it. As the days become shorter on the march toward the solstice, the trees drop their leaves, and we (in Canada, anyway) are teased with the first snowy breaths of winter, the natural world encourages us to consider decay and the possibility of an afterlife in the springtime. The cliché dark and stormy night simply follows a story told by the seasons.

It’s no coincidence that Susan Hill has set both of her ghost stories in the dark and foreboding months in the latter half of the year. Her first horror novel, The Woman in Black, published in 1987 and the inspiration of a very successful (and still running) play, pits a young solicitor against a consumptive ghost who haunts an isolated manor on an English moor. Clearly, Hill embraces the Gothic tradition.

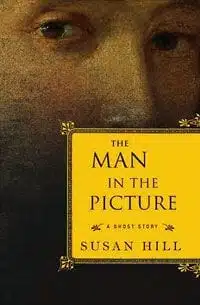

An accomplished novelist of both literary and detective fiction, Hill returns to the ghost story form with her novella The Man in the Picture. Fans of her first ghost story will not be disappointed as she delivers the same blend of Gothic nostalgia, elegance, and luxuriantly long sentences: “The oppression and dread that had enshrouded me a few minutes earlier had lifted, almost as a consequence of what I had heard and of my fall but I was puzzled and I did not feel comfortable in my own skin, and by now I was thoroughly chilled so I made my way back to the college gate as briskly as I could, my coat collar turned up against the freezing night air.” The cold air bites, the fires burn, and the whiskey flows as stories kept secret too long are finally told one long night sometime in the quaint past …

But I’m getting ahead of myself and jumping to the conclusion is something that never happens in Hill’s ghost stories. The suspense remains taut as the tellers of the tale pause, gasp, and forestall their narratives to the reader’s delight.

In The Man in the Picture, Oliver holidays in Cambridge to visit Theo Parmitter, a Chaucer scholar and his beloved former professor. Parmitter, an art collector, has long been troubled by one painting in particular. Seated fireside in his college rooms, and over several glasses of Scotch, the old professor directs Oliver’s glance to an 18th-Century oil painting in the room. The scene: a Venetian carnival. But the painting’s history is just as important as the images it represents.

In just 141 short pages, Hill offers the twisted past of the painting that has a dangerous “hallucinatory” quality over its owners — owners who strangely become the tortured figures depicted on the canvas. To write any more of the plot would ruin a reader’s evening following the tales-within-tales. There is no dead wood in Hill’s plot — it has the economy of campfire story without sacrificing the heightened language of Hill’s Victorian predecessors. The use of the haunted painting invites mentioning Oscar Wilde’s famous The Picture of Dorian Gray. Like the portrait in Wilde’s novel, Hill’s picture reflects the characters’ social and moral lives while serving as a prophecy that plays itself out over and over again.

Perhaps my only criticism of the story is the lack of clarity regarding the painting’s origins. Who painted it? Was it cursed by its creator, or afterward? I suspect Hill aimed for this frustration as even one of her characters wonders in the final pages, “Will there be an ending [to the story]?” Like any good suspense story, Hill leaves the reader wanting more.

Beyond suspense, the true indication of a good Gothic is the author’s depiction of states of mind and, of course, the atmosphere. In this, Hill excels. Consider this description of the Countess (yes, what good is a Gothic without some tortured nobility?), a Miss Havisham type of woman living alone in the requisite Big Empty Manor: “There was nothing decaying, dilapidated, or chilling about [the] drawing room. But the woman who sat on an upright chair with her face turned away from the fire did not match the room in warmth and welcome. She was extremely old, with the pale-parchment textured skin that goes with great age, a skin like the paper petals of dried Honesty.” Hill’s ability to write a well-tuned sentence sets her work as a 21st-Century appreciation of a genre we have been retelling for ages.

Hill’s ghost stories are as much about storytelling as they are about frights. Both The Woman in Black and The Man in the Picture play with first-person narratives and the story-within-a-story device. The refusal to offer a clear conclusion suggests that while ghost stories are fixated on death, the genre is very much a living form that turns listeners into tellers — always with the chilly implication that whomever is privileged to hear the tale might be the subject of its next chapter.