During the 1982 war against Lebanon, Ari Folman was a 19-year-old soldier in the Israeli army. It was, he knows, a momentous experience. But he has little detail, so little, in fact, that he’s not even aware of his loss of memory until a friend describes a nightmare he’s been having. The dream is always the same, Boaz Rein-Buskila says. He’s being pursued by a pack of furious dogs, 26 of them. They race through city streets, smashing past passersby, knocking aside café tables, finally arriving on the sidewalk beneath his apartment, where they pant and growl, their teeth glinting, yellow and sharp in the dark night.

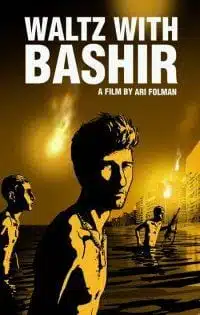

As Boaz finishes his story, he draws on his cigarette and sighs, “This dream is coming from somewhere.” He and Folman are seated in a bar, safe from the nightmare by time and distance — and animation. It’s the start of Folman’s documentary, Waltz with Bashir (Vals Im Bashir), Golden Globe winner and Oscar nominee for Best Foreign Film. Remarkable for its subject matter as well as its form, the film represents Folman’s efforts to recover his experience, to discover why and what he can’t remember. Illustrating his interviews with his fellow soldiers, each with his own version of events, the documentary includes their voices on the audio track (with two interviews re-performed by actors), with talking heads and memories rendered in a mix of Flash and classic animation, as well as some 3D, images at once haunting and provocative.

Folman’s decision to use animation rather than standard interview and archival footage is profound, not only because it rethinks the formal possibilities of both documentary and animation, but also because it rethinks memory — how it informs the present even as it shifts over time, becomes history even as it cannot be fixed. Folman’s journey into his own past is triggered by Boaz’s frustrations and fears: the dogs, he concludes, are reminders of his activity during the war, when he was ordered to shoot down 26 dogs. “Someone had to liquidate them. They knew I couldn’t shoot a person,” he recalls, but now, “I remember every single one of [the dogs], every face.” Folman nods, sympathetic but unable to share his own memories of the war. Boaz is surprised, since Folman was only “200 yards from the massacre.”

That would be the massacre in Beirut, when Lebanese Christian Phalangist militiamen, enraged by the assassination of Christian President-elect Bashir Gemayal, entered the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila and started shooting. Without specific responsibilities, Folman and other young Israeli soldiers watched as the Phalangists, reportedly searching for terrorists in the camps, stacked hundreds of bodies, including women and children, in alleys (the final number of dead is unknown, estimated at 3000). The Israelis’ non-action — the very act of doing nothing — has in Folman’s mind been reconfigured as another sort of lack, of memory and appropriate disturbance, a lack that gnaws at him like the dogs in Boaz’s dreams. The film constitutes his effort to salvage history — to acknowledge official and personal disavowals — in conversations with friends and his therapist Ori Sivan, as well as post-trauma therapist Zahava Solomon and journalist Ron Ben Yishai, whose reporting helped to uncover Israeli Defense Minister Ariel Sharon’s part in the event, as part of a plan to occupy Lebanon, expand the front against Syria: he was found guilty by a special Israeli government commission of having not done enough to stop the slaughter, which took place over two days. Sharon’s culpability is literal and metaphorical in Waltz with Bashir, a reminder that lack of accountability produces horrors, in this and other wars.

Sivan suggests early in the process that Folman’s fragment of a memory — he and other soldiers are emerging from the sea, feeling dislocated, gazing onto Beirut across the beach — is a kind of survival. “Memory is dynamic, it’s alive,” he says. If some missing pieces are replaced by images of events that never happened, this is also part of the process. “Memories take us where we need to go.” Folman’s bit of memory of the beach — he and the other men mystified, reborn into violence, guilt, and fear — recurs throughout Waltz, suggesting his persistent endeavor to grasp the past, to make sense of experiences surreal and unfathomable. Another soldier reports his own wartime experience: asleep on a ship, he dreams that he’s carried away by a giant naked woman doing the backstroke; as he rides her, he sees the ship destroyed: “I watched my best friends go up in flames,” he says, and then he wakes, back on the ship “just before we docked.” Another man remembers his own escape from an attack on his tank, hiding on a beach as the enemy soldiers kill off his comrades one by one.

Dr. Solomon explains such individual dealings with trauma as “dissociative disorder.” She describes another soldier who recovers his combat memories as if he is watching a movie, during which the camera breaks. Here Folman’s film illustrates the rupture, a war zone image punctuated and restructured by cinematic ruptures — projector sounds, distorted focuses –underlining the complex relationship between mass media and collective memory, as well as the reconstruction of individual memories so they are “like a movie,” too real and unreal, lost and found.

At last, the animated memories become too great to bear, and the film closes with photos — the bodies of Palestinians left behind by the killers, brutal, bloody, horrific images. These documents of what happened can’t tell whole stories. And that is the resonant effect of Waltz with Bashir. As it makes visible its distrust of imperfect history and daunting memory, it insists on their necessity. Or again, it insists on the necessity of recovering history and memory amid and because of that distrust.