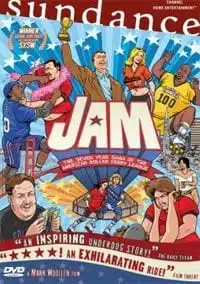

While Jam is first and foremost about the American Roller Derby League, the league owner, Tim Patten, and crew of veteran roller derby stars, this documentary is about so much more than roller derby. Winner of the 2006 South by Southwest Film Festival Grand Jury Prize, this documentary follows Patten and several of the stars of the ‘60s and ‘70s when roller derby drew bigger crowds than major league baseball.

In the quest for roller derby’s revival, the overweight and out of shape stars of the past scrape by in life, consume large amounts of alcohol, and make connections with potential fans. Jam is heartbreaking and layered and is a worthwhile watch but has a few holes that need filling.

For Patten the American Roller Derby League is not a job; it’s a passion. His partner, Dave, says just this as the two scrape together the funds for Patten to pursue these dreams which he confesses is probably what is keeping him alive. Tim is HIV positive while Dave has full-blown AIDS and Tim notes that one thing Dave doesn’t have is a passion.

In one painful scene the two contemplate suicide over lunch and in 2003 Dave passes away. But Tim continues to pursue his roller derby dreams whether there are 20 fans at a game or hundreds of “San Francisco hipsters” looking for the “wildest and most eclectic thing to do” in the Bay Area.

The big ego and “bad boy” attitude of Alfonso Reyes explodes off the screen and his attempts to regain his former glory might be hilarious if he wasn’t such a tragic and touching figure. Reyes and his partner of 18 years, James, bicker about how much beer James drinks and how much attitude Reyes has, especially before games. But James tearfully admits to the camera that without Alfonso he would be dead. Alfonso got him (and his transvestite housekeeper Rita) off the streets, gave him a place to live, supports him and “he asks for nothing in return. Nothing”.

There are many roller derby participants who have big dreams despite how others in their lives feel about this sport. And there are many roller derby players who struggle to make their rather modest dreams come to life. At the same time Jam includes the drama of the rivalry between Patten and his shady business partner, Dan Ferrari, both huge fans of roller derby though Patten is reliving his roller derby days while Ferrari is satisfying his “theater background” (which he mentions often) and desire to “sit on [his] fat ass” and watch roller derby.

Ferrari quickly becomes an ex-business partner and later takes over promotion and production of roller derby games when Patten takes a year off to care for his health. Karey Marengo, who lives with her paranoid schizophrenic brother and struggles for years to hone her skating skills, proudly displays her “Rookie of the Year” trophy to her family and laments that her father is not around to see her achieve her 40-year deferred dream.

Jam is an interesting story about the personalities and lives of the men and women whose dreams seem always just out of reach, but the documentary leaves a big hole that is still bothering me. At one point Patten says that roller derby is still exciting and that no one has been able to properly promote it. They haven’t been able to “put the puzzle together”. At one point he sinks money into the idea of internet broadcasts before he realizes how much money it costs and how little attention this technology is bringing to the sport.

He has big dreams of getting roller derby on television and this seems like the ultimate goal. But this documentary follows Patten and the skaters during a time period when roller derby—albeit in a different form—was on TV.

From 1999 through 2001 there were 100 episode of Roller Jam on TNN (now Spike TV). It wasn’t Patten’s American Roller Derby League, but it was virtually the same thing. And when Patten tried to revitalize American Roller Derby with a “new school” approach, one of his skaters on the Bay City Bombers, Stacey Blitsch, is the same Blitsch who was part of “Bod Squad” and the captain of Roller Jam’s California Quakes team.

Roller Jam adapted the rules and flavor—including in-line skates and teams of seven men and seven women instead of five men and five women. The fact that Roller Jam was on TV at virtually the same time Patten was struggling to make a version of the same dream come true seems like yet another missed opportunity for Patten and other roller derby enthusiasts and a major omission of the documentary. More importantly, this omission is a missed opportunity for Jam to speculate on why this eclectic crew from California is not part of the television dream.

The DVD of Jam includes special features; however, these features were not included with the review copy. Based on the documentary footage, I can imagine that the features mentioned in the press release—A Day with Ann Calvello, Reflections on JAM, Filmmaker Q & A, Trailer, Deleted Scenes, JAM Trading Cards, and Super Fan—would be interesting and insightful.

While much of the pain in Jam is physical, like Larry Lee’s concussion and the regular fighting and violence that is part of this scripted form of entertainment, the real pain is in the lives of the characters that Jam follows.

Toward the end of Jam Patten laments that “sometimes the dream doesn’t come out as shiny and well as you dreamed it” and he attempts to bring “closure” to yesterday’s stars through one final match. But “closure” cannot quell the passion that is roller derby and the dream lingers on.