Early on in Radio Silence, there is a picture of Minor Threat preparing for a performance at an elementary school, unselfconsciously tuning up whilst their “attentive” audience (of 10 year olds) gawps around and picks their noses in boredom. This is a pretty absurd photograph — especially the kid in the right foreground who seems to be on another planet — but oddly fitting.

Hardcore was a movement which (at its best) was inclusive of all ages, unconcerned with projecting a “cool” image, and even innocent in its idealism about the power of music to change people’s thoughts, and to bind a community together. Nedorostek and Pappalardo’s book maps out a history of the genre in the 1980s (at the end of which, some would argue, POST-hardcore took over), with a heavy duty collection of photos boosted by quotes from the some of the genre’s foremost practitioners.

Pappalardo’s introductory essay highlights the cultural background of hardcore — a culture encouraging decadence and superficiality, a right wing gung-ho republican government in power, and an array of punk musicians, such as the Clash and Billy Idol, who had left the semi-independent scene behind to play arena tours. In contrast to this last factor, hardcore was, simply put, harder — bands were (for a start) noisier, but also more aggressive and committed. More crucially, the book reveals just how the music sought to excise star elitism. Gone were the vestiges of rock poseur imagery that had existed within the Sex Pistols and the Clash (the cooler than thou sneers, the occasional guitar heroics, the mystical air); instead, hardcore’s practitioners were simply just people.

This communal spirit shines throughout the book, with snaps of bands looking “ordinary” for publicity shots, posed in playgrounds, and doing gigs directly in front of their audience, not looming down from a stage. The early photographs underline a fact American punk music seemed to grasp faster than its British variant — that self-conscious posturing and fashion statements did not make one anti-establishment, but merely sought to establish a different elite of clothes horses (well, Sid Vicious did look great… ).

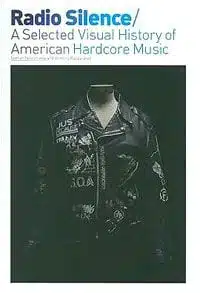

Leading on from this non-elitism is the integration of the fans into the hardcore scene. Radio Silence is full of shots of home made t-shirts, badges, posters, album covers, and fanzines, all produced in an independent scene by kids working off their own initiative. The breadth of these works — some fairly complex in design and execution, others endearingly naïve — is inspiring. Indeed, the last section of the book is a collection of pictures of such art work; testament to the outpouring of creative energy that a scene can produce.

It’s a scene, too, that resisted the sex drugs and rock ‘n’ roll mythos. One of the genre’s pioneers, for instance, Iain McKaye, founder of pivotal bands Minor Threat and Fugazi, as well as the indie label Dischord, was proud to be straight-edged. These bands and their belief in their music exceeded any desire to be some Keith Richards-like character. The concert photos here capture this quite vividly: band and audience members alike radiate a sort of pure idiot (in the sense of one who stands out) energy, where expression bursts forth, and there seems to be little evidence of vain artifice.

Oddly, this is in keeping with some of the ethos of other independent movements in the ’80s underground, such as Calvin Johnson’s K records and the twee/indie pop scene around it, and Gerard Cosloy’s Homestead (which brought out Dinosaur Jr’s first releases). The conservativeness of some aspects of hardcore is ignored (the likes of which resisted attempts by Black Flag to broaden their sound), and the style of some of the gig photos is quite similar (dive bar — check, gurning singer — check, sweat — check). All the same, Radio Silence is an engaging account of a somewhat critically neglected but fascinating scene.