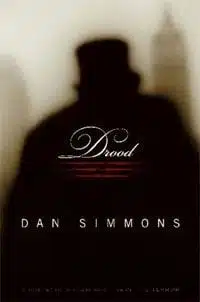

Dan Simmon’s huge headstone of a book, Drood is a combination of literary biography, horror story, detective story, and memoir: the Victorian author Wilkie Collins writing about his friend Charles Dickens. It contains elements of the Sherlock Holmes stories (Collins as Watkins to Dickens’ Holmes), Collins’ own detective novel The Moonstone, a healthy dose of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu, and even the Salieri versus Mozart plot from the movie Amadeus. What Drood is not is “Dickensian”.

While Simmons has taken his title from the last, and unfinished, of Dickens’ novels, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, neither the writing, the plot, nor the characters (entirely devoid of humor, every one) have much to do with Dickens’ fiction. Drood is all Wilkie Collins, and, as we are to learn only too well, Wilkie Collins is no Charles Dickens.

Written as Collins’ “posthumous memoir” to a “Dear Reader” centuries hence, Drood recounts Collins’ literary and personal interactions with Dickens over the last five years of the latter’s life, beginning with the Staplehurst train disaster in June 1865.

Dickens barely escapes injury and as he attempts to help others less fortunate, he encounters “a tall, thin man wearing a heavy black cape.” As Dickens later describes him, this figure “was cadaverously thin, almost shockingly pale, and stared at the writer from dark-shadowed eyes set deep under a pale, high brow that melded into a pale, bald scalp. A few strands of graying hair lept out from the sides of this skull-like visage.” The creature has virtually no nose, only “mere slits opening into the grub-white visage” and “small, sharp, irregular teeth, set too far apart, set into guns so pale they were whiter than the teeth themselves.”

Dickens’ last glimpse of this apparition: “The man’s pale eyes in their sunken sockets seemed to have no eyelids. The figure’s lips parted, its mouth opened and moved, the fleshy tongue flickered out from behind and between the tiny teeth, and hissing sounds emerged.” Dear Reader, meet Drood.

Dickens, we learn, has been much affected by the train accident and his post traumatic stress disorder features an obsession with Drood, whom he imagines wandering through the carnage, ghoul-like, helping the injured into their graves. Dickens not only tells Collins all about the incident, but provides, apparently having done his research, a complete history of Drood.

An Egyptian Fu Manchu, ruler of London’s Undertown, a subterranean city populated by society’s most abject castoffs, Drood is a criminal mastermind, followed by legions of thugs, who is responsible for more than 300 murders. Dickens’ obsession with Drood soon becomes Collins’, and the next almost 800 pages of the book, in part, is a series of horror set pieces in which Collins, sometimes through the offices of a detective Fields, encounters either Drood or his minions. Or, at least Collins thinks he does, which is a problem I’ll return to in a moment.

Drood is also the story of a literary friendship, and its deterioration. Friends and collaborators, who worked together on plays and Christmas stories, Dickens and Collins are gradually estranged due to Dickens growing preoccupation with his reading tours, a phenomenal success in that age, and Collins’ resentment of his friend’s achievements. Generous doses of laudanum and Dickens’ enthusiasm for mesmerism further complicate things.

Throughout, the story of Collins’ obsession with Drood (and two lesser apparitions, which have populated his imagination, and his home, since childhood) is intertwined with his obsession with Dickens, which eventually leads Collins to the conclusion that he must murder “the most famous author in the world” (as we are reminded he is time and time and time again).

Now, the historical Dickens wasn’t murdered, which represents a challenge to the author, who has apparently tried to be as truthful as possible to the historical record. Yet, Collins does murder Dickens, or seems to. Skip the next paragraph, if, like me, you hate hearing how a novel ends before you’ve read it.

I wanted to like this book. Dan Simmons can certainly write, his sentences are clean and precise and rarely flowery (nothing like Dickens). I love Dickens and horror and detective stories, all the various elements of Drood, which should make a pleasing concoction. But you can’t cheat. And Drood cheats again and again.

The murder of Dickens, exquisitely described, is quickly revealed to be that poor last refuge of creative failure, a dream. Collins commits other murders. Or does he? We are given all the factual evidence that he has, but in a long desultory ending the author leaves us with a big question. Has it all been Collins’ fantasy, engendered by a few mesmeric suggestions from Dickens at the beginning of the book, and fueled by opium and the writer’s own hyperactive imagination? The answer is, probably. And Drood? Well, I won’t give away everything.

I might have forgiven all this if the journey had been more pleasant. Seven hundred and seventy-one pages can feel like two thousand when you’re told the same thing over and over again. Perhaps, in a book this long, to be reminded two or three or four times of something that took place earlier on might seem helpful, but after a while it feels like the author thinks the reader is dumb.

There are a number of great scenes in the book: the Staplehurst disaster is vividly described, a first (not the second) descent into Undertown is scary, and a literary argument between a high-handed Dickens and Collins is perhaps the most engrossing scene of all. But, just as often, Drood relies on horror clichés. On page 313, Collins say, “I do not mind telling you, Dear Reader, that I was terribly weary of crypts. I do not blame you if you are as well.” This is fair warning, for a lot more time spent in crypts is yet to come.

Finally, even with these caveats, Drood might have been worth the ride if Dickens, and Collins especially, were more interesting characters. The portrait of Dickens is clear, if not vivid, but being inside Collins’ airless crypt of a brain is punishment indeed. He is a man without passion or conviction. He is obsessed only with Drood and Dickens. Even his feverish literary pursuits are enslavement to these obsessions. I suspect that given Simmons’s premise for the book, he felt it couldn’t be otherwise. But that doesn’t keep his Wilkie Collins, however many horror stories he has to tell, from being a bore.