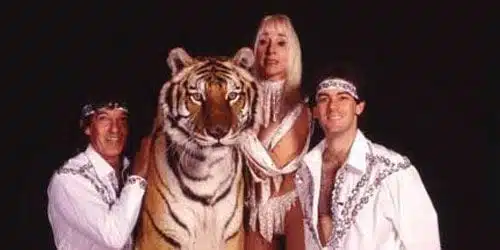

Cat Dancers tells the story of Ron and Joy Holiday, a husband and wife team of cabaret-esque ballet dancers who felt the need to spice up their act. They did so by adding trained wild cats, first a panther, followed by more exotic and unpredictable cats like leopards, tigers and jaguars to their performance, prefacing more famous acts like Siegfried and Roy.

As their traveling act became more successful, the Holidays brought a third person into their act and into their lives, Chuck Lizza. While Lizza starts out as just an animal trainer and stagehand, he eventually becomes involved in a love affair with both Ron and Joy. The trio’s unconventional lifestyle comes to a sad and brutal end when Lizza is killed by Jupiter, the act’s prized white tiger. This tragedy is further punctuated a mere three weeks later when Joy is killed by the same cat, leaving Ron Holiday alone, his lovers dead and his life in shambles.

The main problem with Cat Dancers is that while the relationship between Ron, Joy and Chuck is admittedly a little strange, it’s honestly not all that compelling of a tale, and without something very noteworthy to anchor it, watching the trauma that eventually unfolds just seems lurid and voyeuristic. Another fault is that Ron is nothing if not a consummate performer, and his interviews, which guide audiences through the narrative, seem somehow scripted, and his mugging for the camera at odds with the intimate nature of the film.

One gets the sense throughout that another perspective, one less close to the situation, would do make the story more compelling. But the Holidays and Lizza made for a close knit clan, and there is no one left but Ron to bear witness to this sad tale. Between an at best uneven series of narrative interviews and less than stellar stock footage visuals, Cat Dancers simply doesn’t make for particularly watchable cinema. Ultimately, viewers are left with a film that feels less like a thoughtful exploration of a sad tale and more like an excuse to gawk at a particularly brutal and private tragedy.

After Chuck Lizza’s death, it’s hard to understand why Jupiter wasn’t put down, if not by the Holidays, then by the authorities. Footage of the cat taken by Joy in the weeks before her death shows her shaking badly as she holds the camera, and betrays her growing fear of the animal. The trainers interviewed in the films special features are of one mind concerning the deaths of Chuck and Joy, put most bluntly by trainer Jay Riggs: “The first one is an accident. The second one is a preventable accident.”

Every trainer interviewed in the special features makes the point that after the death of Lizza, the only sane choice was to isolate Jupiter. The Holidays did not make that choice, and it ultimately cost Joy her life. But why that choice was not made is never even posed to Holiday, and seems a glaring omission on the part of director Harris Fishman, especially in light of the fact that Ron Holiday himself recollects that the tiger was added to the act at his insistence, and in spite of the protests of his wife.

“Joy said they were mostly inbred, and that we shouldn’t do it,” Holiday says of the decision to add Jupiter to the act. “And I pushed it and pushed it.” Holiday obviously regrets the decision to push for the introduction of a new and dangerous x-factor into a stage act already full of them. But the filmmakers choose to simply feel sorry for Ron, rather than really explore the group dynamic and the decisions that led to the terrible climax at the heart of the film.

It’s often appropriate for filmmakers to feel sympathy for their subjects – indeed, it’s hard not to. But that doesn’t mean it would have been inappropriate for them to ask Holiday a few tough questions about his role in what happened. Since this is never done, Cat Dancers comes off seeming less concerned with the story it’s telling than the person who is telling it.

It is only at the close of Cat Dancers that we get a sense of Ron Holiday actually talking about what he has lost, rather than performing a monologue on what he once had. In the aftermath of being forced to put his two remaining cats down, Holiday finally loses control – the ties to his past and the greatest loves of his life have been severed, and the enormity of it finally shows. It’s in this scene, and sadly in this scene only, that we get a sense of who he really is, of what he has truly lost and of how it weighs on him. It’s just a shame we weren’t introduced to this person earlier in the film.