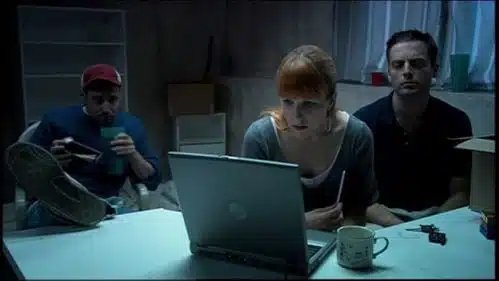

At what point of “meta” does it all become one giant tiramisu of bullshit? Of course, I can’t delve too pointedly into that question without revealing the Mouse Trap tricks and plots turns of Four Boxes. What I can say is that it appears to be a generational satire built around the story of two internet liquidators (people who sell off the junk of the dead on eBay) who discover a mysterious website called Four Boxes. Ostensibly, the site used to be the website of a slutty exhibitionist woman who moved out and kept the cameras in for the unsuspecting newcomers. What follows is the morality play of three inter-fucking friends (I see a trend) who watch what appears to be torture, murder, and intricate terrorist plot unfold. Four Boxes moves at the indie thriller pace that it should and Justin Kirk (of Weeds fame) makes a credibly brooding lead. But several of the satirical gestures either grate too much or make the viewer question whether the writer is satirical or envious. I don’t hang out with a lot of people much younger than I am (full disclosure: 35), but do the people in their mid-twenties, who are supposed to be represented here by people clearly older, really speak in instant messaging speak? It’s a travesty of content-free exclamation whose abbreviations only accentuate its scarcity. It’s difficult to sit through and seems more of a worst-case scenario than a lingua franca of the young ones. It reminds me of the vicious backbiting against the valley girls, whose dialect was also a slang-ridden avoidance of depth. But how many of us actually ever met a valley girl? It’s possible to be so vehemently critical that you give the object of criticism an easy out on the caricature clause?

Many of the themes that run through Four Boxes merit exploration. I think it’s true that normal existential angst has been medicalized to the point where having passion is itself a pathology. But is that purely a function of too much internet and not enough face-to-face? The characters are the tech-savvy undead: On cell phones, using webcams, checking their social networking sites every five minutes, and hollow in a way that deserves to be addressed less flippantly. “Life sucks. Life really sucks,” seems to be as close a summary sentiment as we can get in the film. But why do the characters have such deep disconnections from empathy in their acceptance of violence, suffering, and sexual disconnection. There’s “kid’s today” and there’s “Ted Bundy” and while I personally feel like the greatest achievement of the generation after me so far as been the Lolcats, I’m not willing to write them off as collectively lost. Nor are any of the film’s cultural critiques confined to any particular cohort. Traditional work, marriage, kids, death patterns in the American social experience have been disrupted for decades by everything from the birth control pill to gay rights. I guess I just don’t ultimately understand what Four Boxes is critiquing or saying or whether its simply trying to capture a zeitgeist and make fun it. But it does grow tiring having to create that much context for the meaning on the screen. I don’t mind working for a movie, but I gotta get paid. In a certain sense, there’s probably enough pay off here to make Four Boxes worth watching. It has its creepy moments, like the grainy, furtive webcam movements that suggest untold mass terrorism. Despite characters that dissolve into characterizations, it’s difficult to pry yourself away until the final fade out. The ending is pure punchline; I had to grant the filmmakers the last laugh with a twist that no one would have predicted. But good satire needs much more than just an unforgiving eye; the best satire is both diagnosis and cure, a window into a different way by tweaking the excesses of the present. In the end, I don’t know who the film is talking to or what it’s taking about; the rest is just an Escher stairwell into pure speculation. That’s not my job.