Set in 1938 in a desolate, mournful Albany, Hector Babenco’s Ironweed is a surreal, almost detached look at the lives of a group of alcoholic drifters that never flinches from the story’s desperation and sadness. With a stark autumnal color palette reminiscent of Edward Hopper’s surreal green, gold and red late-nightscapes, where strangers meet in bars at ungodly hours, the film captures a slice of life that can be, at turns, touching and revolting. This is, essentially, a bleak two-plus hour look at lost souls with nowhere to go.

In a time of national financial crisis, the bitter-cold Ironweed also serves as a cautionary tale about the kind of slippery slope people can fall down when jobs are scarce and accidents seem to pile on top of one another. A chain reaction of bad luck all but sinks Francis Phelan (Jack Nicholson) throughout the course of the film. You get the sense from watching this film that this kind of life can happen to anyone, at any given moment, if one incorrect step is taken. With the deluge of lay-offs and foreclosures permeating the front pages of newspapers across the nation, it likely is happening as we speak.

Where do you go when nobody wants you anymore? How do you change when you are caught in a completely hopeless situation beyond all control? These are questions that are highly relevant to Ironweed’s milieu, as well as to our present-day economic quagmire. History is repeating.

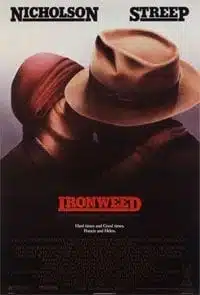

Besting Robert De Niro, Gene Hackman, Paul Newman, Jason Robards and Sam Shepard for the leading role of Francis Phelan, a degenerate lush with a crooked past and a misguided heart, icon Jack Nicholson gives one of his most complicated, consuming performances, unlike anything else he has ever done. Pulitzer Prize winning author William Kennedy, who also wrote the effectively sparse script, packs Francis’ story with enough gut-punching details to keep viewers riveted throughout; a feat considering how relentlessly dreary and interior the story is.

Forced into sharing the perspective of the mentally-ill addict who has returned to his hometown after many years one dour Halloween, Babenco and Nicholson never make Francis pitiable to their audience, and, in many cases, endow him with a purity of heart that few are able to look past, given his flinty reality.

Ironweed opens with a shot of Francis laying in the gutter with cigarette butts and broken glass and doesn’t pull a single punch in depicting what life was like for vagrants, low-lifes, thieves, alcoholics, street people and tramps of the time. It is cold and he is homeless. There is nothing at all charming about his life. The only work he can get is digging graves for pennies (“my own”, he cracks without the slightest hint of irony).

In its extreme morbidity and sadness, there is a respectable grain of truth that Babenco (Kiss of the Spider Woman, Pixote) clings to, never pandering to his audience or giving them an easy way out. Francis is a man who is haunted by death – death of a child (which triggered his subsequent descent into homelessness and depression), death of other men by his hand, the dissolution of a marriage, and the failure to achieve any modicum of success.

Every day on the streets, death surrounds him in the form of the living dead who populate this underworld he inhabits. If anything, Ironweed is about the death of dreams, but particularly of the American Dream, which in the film’s universe, is non-existent. This darkness, the despondency of a simple drunk day-laborer’s pain as it consumes him propels the film along even as human train wrecks die in the street and are eaten by packs of rabid dogs.

Through a series of hazy, alcoholic flashbacks, Francis’ back story unfolds. He hallucinates and sees the ghost of a “scab” he killed when he was a young man. The scene transports the viewer in and out of reality, mimicking a volatile, disorienting alcoholic fit. When he yells out at this apparition in public, we see that he is, in fact, the only person who sees this image. Then, two more men Francis murdered begin to heckle him from beyond the grave.

Curiously, despite matching Oscar nominations for stars Nicholson and co-star Meryl Streep, the film was considered a failure in its day; proving that when it comes to big stars taking even bigger risks, there is only so much the ticket-going public will tolerate. Seeing the beloved Nicholson and Streep wallowing in misery and poverty, complete with bad teeth and tattered rags hanging around their necks for warmth, proved to be too much of an artistic challenge for audiences. There is no respite here. No gloss. There is brutality and desolation in spades and no Hollywood ending.

What the film does show, however, are the abilities of the artists to test their limits and challenge their own artistic limits – and both Nicholson and Streep give outstanding performances as lost souls who couldn’t make it out of the Great Depression intact. Both actors, in general, rely on their respective personal legends to endow performances with enough flavor to let their own charm shine through, often to schtick-y effect.

This is definitely not the case with Ironweed, where all traces of performer are obliterated in favor of a deep, raw exploration of character. No tics or mannerisms or personal charm can be found here, thankfully. These characters are not going to dinner at The Ritz. Often, they don’t get dinner at all. They are both highly unlikable. Achingly, they press on despite all odds being against them, not unlike millions of Americans who are losing their homes as we speak. “I believe you die when you can’t stand it anymore,” says the pained Helen, who must dole out sexual favors to fellow hobos in exchange for a place to sleep off the booze.

Nicholson balances psychosis with a hearty working class sensibility that is lived-in, harrowing and haunting. It is a true departure from all of his other characterizations. There is, unapologetically, no trace of “Jack Nicholson” found in Francis, save for perhaps the darkest, most private edges. It is so nice to see a star so completely bury his public persona, and we are reminded of exactly why this man is a legend: his ability to act. Covered in a layer of grime, Nicholson is fearless and expressive, even as Francis’ sanity becomes fleeting. Opposite Streep, in an equally brave, unheralded performance as fellow bum Helen, the legend finds a perfect foil.

The single element that brings down the entire film is the grainy, cloudy DVD transfer, which doesn’t look good, whatsoever. It looks as though someone used a busted VHS tape as the source material for this disc. As this is the film’s debut to DVD, and it features two American legends at their most exploratory, it deserved much better. The quality of product definitely does not match the quality of the film and the performances; in fact, it does them an extreme disservice.

The lack of any interesting extras (a paltry photo gallery and a trailer is among the weak, perfunctory offerings here), is also detrimental to the release, making it feel as unwanted as its characters. While on one hand, it is nice to be able to see the film at all, it would have been nice to see it cleaned up with a hi-def transfer and perhaps a commentary or interviews with the principles.

As it stands, I would recommend skipping this garbled edition altogether, as it is an utter waste of money and time. You would be better served to find a newer video tape, waiting for it to play on cable, or even holding out for a better DVD somewhere down the road. Seeing the film as it was meant to be seen is worth the wait.