If you take the time to ponder how anyone became involved in Fighting, you might consider this. Roger Guenveur Smith plays a hood named Jack Dancing. It’s not a great reason to take the part, a disagreeable and small-minded man with precious few minutes on screen. But it is a reason, a name just curious enough that you might eke out a character from it, even given that the film around him offers no help whatsoever.

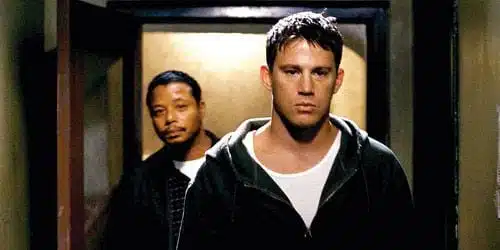

Smith’s Jack Dancing is one of those snidely movie villains who deserves his inevitable punishment. As you wait for this turn of events, he shows up in various locations, lording it over the underdogs — here, underground fighter Shawn MacArthur (Channing Tatum) and his sorta manager Harvey (Terrence Howard), who happens to be Jack Dancing’s ex-smalltime crime partner — so that they hang their heads and fret, mulling over… something. Maybe how they became involved in this movie.

Lacking the allusive lyricism of a name like Jack Dancing, Shawn and Harvey wallow in Fighting‘s frequently unfathomable mix of banalities and corny quirks. They meet awfully cute. Shawn, just trying to earn an honest illegal living selling books off a blanket in Rockefeller Center, finds himself the target of a couple of baggy-jeansed thieves. Shawn fights back, skillfully enough that he impresses Harvey, who’s on site because the thieves are working for him. Shawn gasps and clutches his blanket, sans his wad of cash, while Harvey looks on in a series of approving reaction shots.

A couple of scenes later, Harvey has his chance to pounce, when Shawn spots him through a diner window and demands his money back. They shift their weight and posture, Shawn revealing once again that he’s a genuinely nice kid who just happens to be a skilled fighter (his dad coached a wrestling team back home in some Southern Elsewhere, and Shawn had a traumatizing falling out with him). No matter. Harvey soon has the kid convinced that he can help him make money by fighting. You know, like the movie title.

To this end, Harvey must secure initial financing from Jack Dancing, a former partner with whom he shares a minor criminal history, as well as a third term/friend, Martinez (Luis Guzman). Jack Dancing scoffs at the new prospect, despite the fact that Harvey has dressed him up in his own sport jacket to make a good impression. He went to college, lies Harvey, suddenly desperate for a hook. “A white guy who went to college,” Jack Dancing sneers, “How come I never heard of that?”

Thus established as inscrutable and — in this by-the-numbers plot — intriguing, Jack Dancing is quickly sidelined, so the film might focus on the white boy’s progress. Each match offers a larger payoff, with each opponent more skilled and each audience more invested. They begin in Brooklyn, head over to the Bronx, and end up in Koreatown — its exoticism marked by the leggy cross-dresser who comes on to one of Harvey’s doltish crew members. No matter the style of fighting or size of his adversary, Shawn finds a way to win. He seems less skilled than lucky (one guy goes down when he hits his head on a porcelain water fountain, another fight is stopped when a spectator pulls out a gun and starts shooting), but still: being the luggy underdog hero, his wins can’t look too easy or too likely.

Shawn’s ascent is, of course, premised on his bonding with Harvey — to the point that Harvey invites him to move in with him. This also has something to do with Shawn’s background, as he seeks a father figure and holds a grudge against the black wrestler (Evan [Brian White]) who became his dad’s favorite. But the film isn’t about to sort out all the race and class tensions it sets in motion. Instead, it stages a couple of heated arguments between Shawn and Harvey that never quite get at what may or may not be at stake.

To assure you that there’s no sex at stake, Fighting gives Shawn a girlfriend, Zulay (Zulay Valez). Yes, it’s awfully convenient that she was a witness to his first street fight over the books, that she’s a waitress at a club where the underground fighters hang out, and also that she knows Evan and Jack Dancing. For these contrivances she may be forgiven, if only because Zulay brings with her an adorable little daughter and an incongruous if understandably skeptical grandma (Altagracia Guzman), whose first assessment of the interloper is, “He look like a criminal.” Their cramped apartment and grandma’s late night repasts and ongoing commentary (“I don’t understand what you talk”) provide a welcome respite from the fighting world that takes up so much of the film’s time.

But such relief is short-lived. The universe of underground fighting is small, you see, and Shawn must make his way through a few more too-convenient encounters and connections. Not to mention crash through some windows and walls during a big finale fight. So what if you never quite know why Jack Dancing has money or how he’s come to despise Harvey so deeply? Or whether Harvey is or is not “manic depressive”, as a couple of whisperers insinuate? And why even begin to wonder why Jack Dancing quotes “the late great American poet Marvin Gaye” to start a fight (“Let’s get it on!”)? Shawn is, as Zulay says, “like a knight”, come to rescue some folks and punish others. Why would you even start to contemplate his whiteness?