If you were looking for fresh sounding jazz in the ’60s and ’70s, there were plenty of “out” sounds to dig, and eventually there was the beginning of fusion music, amped up with funk and acid guitar. It was a time of change, and harsh, bracing change was at the door.

But change and progress need not always jar the ear. And in jazz, the proof of that is Gary Burton, the gentlemanly king of the vibraphone. He got his start in Nashville at a young age, then played with George Shearing in 1963 and Stan Getz from 1964-66. But real notoriety came with the first group under his leadership. The Gary Burton Quartet was tuneful, melodic, and accessible—yet it was also a bold experiment.

Jazz Meets Rock, Gently

“I was casting about for a concept for this band. What are my roots? What do I have to focus on? I grew up in the Midwest and started my career in Nahsville with country musicians in my early 20s. I was a big fan of early rock music—Elvis and the like—but in the mid’-60s rock became more sophisticated and interesting to musicians. And there I was ready to start my new jazz band.”

Burton’s solution was to construct a quartet that was a little bit classical — “I modeled it after a string quartet in that I wanted equal roles for the instruments and equal interplay between them” — but also based around the electric guitar. His first guitarist was Larry Coryell, who would go on to a blazing if unconventional career in fusion as well as more mainstream jazz. In the rhythm section, he added fiery drummer Roy Haynes and a Getz bandmate, bassist Steve Swallow. A year later, in 1968, Gary Burton was named Downbeat‘s “Jazzman of the Year”.

What made Burton’s early music suggest rock? Certainly, featuring a young guitarist was one element. But this was never heavily electric music. “It just seemed like the right thing for me to bring elements of county and rock into jazz. But I didn’t go the same direction as what later became fusion music because of the nature of the vibraphone. It’s a softer instrument, and that kept my music more melodic and lyrical.”

Specifically, Burton focused on adapting the simpler harmonic structures of rock. “In most jazz of that era, you would never play a major triad, unadorned — it was considered too plain. But in rock and country this was a pretty standard harmony. We had tunes that featured this kind of harmony, and to some people, this suggested country or rock.”

A New Fan, A Young Bandmate

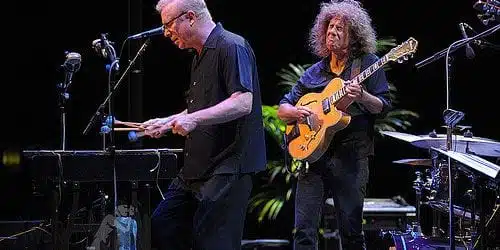

Young folks were immediately attracted to the sound of the Gary Burton Quartet. Some were inspired to pick up an instrument, like perhaps the guitar, because of Coryell and Burton. “I met Pat Metheny at a college jazz festival in Kansas. I was the guest player with the host band, and Pat was there with a small group. He walked up to me and introduced himself. My group was his favorite, he told me, and it was reason he started playing.

“Pat said, ‘I know all your songs—may I sit in with you?’ He played on one song, and I listened to his small group. He was quite promising. He asked me for some advice, and I said, ‘Leave Kansas.'” Six months later, Metheny arrived in Boston — where Burton had started teaching at the Berklee College of Music — and the two became friends.”Soon I hired him to be in my band.”

Metheny spent three critical years in the mid-’70s with Burton’s quartet, recording three classic albums for ECM with the band: Ring, Dreams So Real, and Passengers. Burton and Metheny seemed tailor-made for each other—both Midwestern kids from Indiana and Missouri respectively. “Pat grew up in Missouri and was exposed to country and rock — and he told me that he related to my band from the start.”

On all these records, Burton had another critical partner in bassist Steve Swallow, who had been with him in Getz’s band. “Guitarist Jim Hall told me about Steve Swallow. I got to know him, and when Stan needed a bass player, I recommended him. When I started my own band, I convinced Steve to come with me. For 21 years, we played together. The great thing about Steve is that he was my advisor. I talked over everything with him—what tunes to play, what direction to go with the music, what musicians to hire. He was wonderful at helping to guide the group. I had a partnership with him over those years.”

And So: Reunion

Before the ’70s were over, Metheny had made the first few of his own group’s albums on ECM, and his career in jazz would leapfrog Burton’s, achieving the popularity and critical respect that almost never go together in jazz. Swallow also left the Burton group eventually, playing more and more with Carla Bley and many others.

But several years ago Metheny was the featured guest at the Montreal Jazz Festival and got the idea to play one of his concerts with Burton’s then-current group. “He called me up, and we thought it would be fun to play some of the songs we used to play together. We thought it would be a one-time thing, but the concert went so well and we had so much fun that we started talking about playing some more concerts and doing a record.”

That record, Quartet Live, was recorded in June of 2007 at Yoshi’s, the great San Francisco jazz club, and was released this month. Now the reunited group—Burton on vibes, Metheny’s guitar, Swallow on bass, and drummer Antonio Sanchez—is about to go on its third tour together. The recording is a straight shot of nostalgia if you loved those classic ECM recordings, but it sounds remarkably up to date as well. If standard jazz-rock “fusion” has aged about as well as un-refrigerated bologna, then this music is something else altogether: fresh, still fresh, probably because it was never based around gimmicks or effects but rather musical verities. The melodies are still engaging and the sound of the group is actually improved by a clear recording and a sense of mature ease. The group remains uncluttered, very much like the string quartets that Burton imagined them to resemble.

Quartet Live & Movin’ on

Swallow photo (partial) from Klaus-Muempfer.de

Quartet Live

The new record features songs by the same mix of composers the group favored during its first run: Swallow, Chick Corea, Carla Bley, and Burton and Metheny themselves. The classic Swallow tune, “Falling Grace”, is taken quickly but with the same beautiful cascades of harmonies. The band now swings this feeling more easily and a bit harder than before, with Sanchez skipping them forward joyously. The ballads, such as Keith Jarrett’s “Coral”, have a deeper melancholy as well.

The three Metheny tunes return as some of the strongest writing of his career. “B and G (Midwestern Night’s Dream)” has a cinematic scope and the surprise of the new, with harmonies that would never have appears in a bebop song. On the other hand, “Question and Answer” seems even more classic now — as if someone should write lyrics for it. The soloists, like the jazz players they are, all seem wiser and freer with some age. Metheny still has a joyous ease in his phrasing, and his classic sound remains his signature. (“That sound came together during the first year or so that he was in my band. He was experimenting with different amps, different guitars, and different settings. He definitely heard something that he wanted for his sound, and around the end of the first year in the band, he had found it.”)

Today, the improvisations sound more carefully constructed, as if a very logical and fearless architect was building them to stand for a long time but never bore you. Burton’s sound remains unfussy but beautiful—a kind of decorous version of Bill Evans, but on an instrument that peals with a smile on its face. That said, Burton seems to be playing more blues than ever before in his life, giving more guts to just about every phrase. Swallow, quite simply, gets more and more nimble with age. His signature fretless electric bass has not lost a step, still glittering in the sun, like a river on the move in the pure air. The interloper here is drummer Antonio Sanchez, who has been playing with Metheny for years. He adds immeasurable grace and propulsion to the group.

What Quartet Live lacks in freshness — it is, after all, defined as a retread of music from 30 years ago — it makes up for by reminding us that what started as a novel idea has become immune to fashion. Gary Burton’s lopingly melodic jazz/rock/country sounds, today, simply like great jazz. You listen to Metheny’s “Missouri Uncompromised” and you might hear those simple harmonies or the twin-leaders’ fly-over boyhoods, but more likely you hear Sanchez’s driving swing, Swallow’s restlessly melodic bass line, and two first-class improvisers who arc across the tune with great imagination.

Pat Metheny photo (partial) found here

No Gray Eminence

Though Gary Burton is now in his mid-60s, it is hard to hear his music or see his career as having settled into a period of eminence. Speaking to him is a polite but puckish experience. He seems, if anything, restless for his age, interested in going everywhere and playing everything.

“Some musicians have one thing that they do, and they do it really well, and they make a career out of it. Like Milt Jackson — one of my heroes — played basically blues and ballads. Other musicians in the jazz field are what I call ‘world travelers’ who have curiosity about lots of things. They try something with a symphony, or something with Indian musicians. Miles Davis was great at this. He tried orchestral music with Gil Evans. He tried some electric music. I find, if you can imagine yourself playing along with it, then you can probably do it.”

That’s why Burton has trail-blazed, playing with his groups, working in myriad duet encounters, playing tango music with Astor Piazzolla, you name it. “I like to think that I’m enough of a musician than I can adapt to other players’ genres and find a common ground. Some of the most interesting music I’ve played over the years has been in these collaborative situations with some else’s music that I don’t know that well.”

And so Burton is back out at it again, now five years into retirement from his career as a professor and administrator at Berklee. He’s back out on the road duetting with Chick Corea, touring with Metheny and their quartet, working with an all-star band through Europe. “Right now I have the freedom of not having a regular band to support. So life couldn’t be much better.”

Vibes, Terrific

All of this from playing a crazy instrument that hardly anybody even understands or can identify. “I do think occasionally about how unusual it is to make a living playing jazz on the vibraphone. There have been successful vibes players through the years, but relatively few. It’s an instrument that is only visible in jazz (and Hawaiian music, but we don’t talk about that). Most people I meet don’t even know what the vibraphone is.”

Burton defies most categories and definitions, in fact. He is one of a relatively small number of openly gay jazz musicians, a subject he has been happy to talk about for many years. But if Burton’s sexuality is as novel as his instrument in jazz, he seems also to be the most “normal” and centered of all jazz musicians. Talking about jazz and about his instrument’s role in the music still makes him seem boyish and excited.

“The vibraphone is a newish instrument. When I started playing in 1949, people were still learning how to play it and no one had started their career on the vibes.” For a while, Burton recalls, people didn’t even know what to call the set of bars and resonator tubes — the “vibraphone” or the “vibraharp”. But what does it matter if the music is this glorious?

“Lionel Hampton made the first record using vibes with Louis Armstrong. Louis hired a band in Los Angeles with Lionel on drums, and he noticed Hamp occasionally would reach over and pound away at these bell-like things. He asked Hamp to bring them along and in 1931 they recorded a Eubie Blake tune, ‘Memories of You’.”

About 80 years on, here is Gary Burton, still pounding away at these bell-like things, making it all come alive every night.