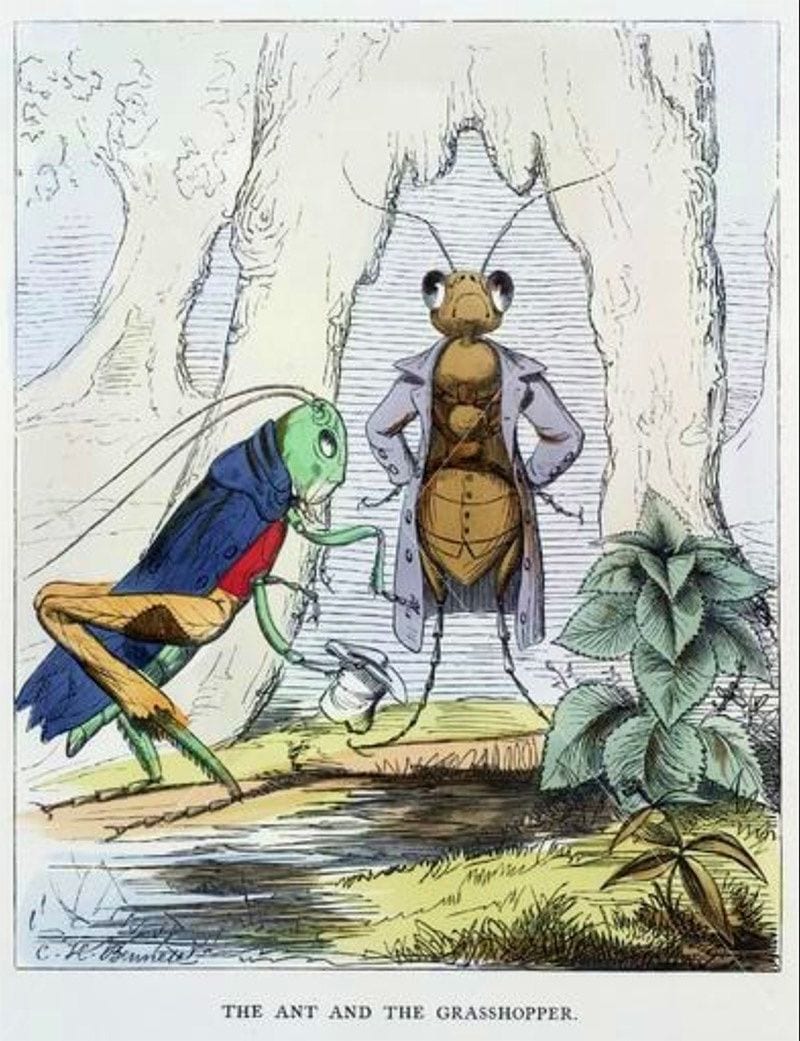

The current US presidential administration proposes merging the Departments of Education and Labor. After all, the White House’s rationale insists, they’re both aiming at the same goal: the workplace dictates student outcomes and management expects compliant employees. Whether Aesop’s fable of “The Ant and the Grasshopper“, C.P. Snow’s divide between the humanities and the sciences as “The Two Cultures“, or the slow decline of the liberal arts in academia contrasted with the rapid rise of business majors, these gaps expose cultural and economic tension.

Jennifer Summit and Blakey Vermeule taught a course at Stanford on this dichotomy between the cultivation of wisdom and the demonstration of skills. Action Versus Contemplation: Why an Ancient Debate Still Matters begins with an appeal for balance rather than conflict when these two realms are juxtaposed. The classic busybody and lazybones characters reveal to the authors not only conflict in the university but a battle between stress and relaxation engaged in by many of us. Activity without leisure proves meaningless; downtime without engagement turns purposelessness. Summit and Vermeule, trained as literary critics, aim this brief book towards those who seek to recover a wise balance while never dismissing the life of the mind.

They delve into the ancient and Renaissance divisions between theoria/ “useless”/ elite and praxis/ “practical”/ laborers. The authors posit that a caricatured standoff between fuzzy and techie contingents in Silicon Valley fades as cross-pollination unites two cultures. They pinpoint 1459 as the date when the ideal of “humanitas” emerged as distinct from practical endeavors. Five hundred years later, they chart when the ’60s-era celebration of dropping out mingled with the ’70s-era promotion of the small-press bestseller, What Color Is Your Parachute? This earnest trend pivoted from going back to the country and accelerated into “deep happiness” obtained from a “self-knowledge” which would pay (sub-)urban bills while somehow satisfying one’s inner child, as if long lost lazy summer afternoons could be resurrected.

Halfway through this concatenation of topical chapters—presumably the result of the pair’s collaboration and division of labor—the fabled insects’ reprise this conflict through entertainment for the masses. Disney’s 1934 “Silly Symphony“, the French storyteller Jean de la Fontaine, and John Lasseter and Andrew Stanton’s 1998 film A Bug’s Life, exemplify treatments of the titular “ancient debate” in pop culture. The authors treat the last in this list as indicative of today’s youth, who seek creativity within community.

This return to a differently domesticated idyll than that romanticized half a century before by the hippies marks two representative texts as case studies. Sue Bender’s 1989 Plain and Simple: A Woman’s Journey to the Amish complements Marie Kendo’s 2014 The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up. Their surprising publishing success illustrates the appeal for a primarily female readership of a “New Domesticity”. That is, not a retreat into the home but a self-help regimen to repair the imbalances of late capitalism. This book’s value derives from its array of diverse ideas from religion, literature, and art. But stretches plod along with intermittent scenes of interest, most reliably engaging whenever media portrayals loom.

Summit and Vermuele predictably add their tones of the seminar and the professoriate to this material. Their cosseted perspective from serving, living among, and observing the Bay Area’s privileged classes limits its scope. Yet their theme of how setting things straight in our daily lives, whether in chores on “time off” or duties on the clock, dominates present-day concerns in a blurred work-life continuum will prove relevant to many readers caught in this far from polarized predicament. The authors reason how redemption of accumulation and activity may be elevated within our material age. Adapting Charles Taylor’s influential 2007 study of secularism, A Secular AgeA Secular Age, these scholars define strivers for meaning who strive for “a sanctification of ordinary life.”

Finally, Summit and Vermuele argue for not “sanctuary from the outside world” but instead “a microcosm modeling an ordered world” as viable. They support integration of public and private space. They look back at the pairs of women who entered fiction as dramatizing these opposite loyalties. Leah and Rachel and Martha and Mary’s opposing character types from the Bible, and Barbara Kingsolver’s narratives typify this strain of searching for authenticity, pursued in impractical downtime rather than necessary tasks. Whether it’s the heroines of George Eliot’s Middlemarch or politician Hillary Rodham Clinton, official narratives from Bartleby and Kafka, or David Foster Wallace’s reporting on Tracy Austin’s tennis career, tales from celebrities and classics fill the short shelf where play and duty overlap or clash.

This section expresses in livelier style the impact of these positions. Billions grapple with a frenetic paradigm shift which scuffs lines between a carefree ant’s and a diligent grasshopper’s domains. Peter Drucker’s prescient coinage of a “knowledge worker” (The Landmarks of Tomorrow, 1959) epitomizes this social drive; information replaces manufacturing and manual labor means data control. The Space Age dream of an automated age of fewer demands, higher income, and happier hours remains deferred. Retirement retreats into a feared future of McJobs, gig economies, debt, and depleted bank accounts. Some of this survey’s audience profit via the security of tenure or the surety of pensions. For the rest of us, how downtime, kicking back, and chilling out, whatever the slang, will survive this occupational whiplash stays a conundrum.