If asked to comment on the forces and pressures that have shaped encounters between Europe and the Near East since the end of the Roman Empire, many educated people would describe long-term and still-deepening fault lines between historically Christian and Islamic societies. This view is epitomized in Samuel P. Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations (1996) and Roger Scruton’s The West and the Rest (2002). Others will point to cycles of unrest and legacies of destabilization associated with Western colonialism in Muslim territories since the late 18th century. A versions of this view appears in Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978).

I imagine comparatively few would arrive at identity as a framework for understanding interactions between Christians and Muslims in the early modern period. Agents of Empire (the full subtitle is Knights, Corsairs, Jesuits and Spies in the Sixteenth-Century Mediterranean World) is certainly not a work of philosophy, and Malcolm does not theorize or extrapolate on identity or on anything else, in the manner of the foregoing authors. But the matter of identity and self-identification is a provocative spectre throughout.

Noel Malcolm’s stated hope is to build a thematic account of the relations between East and West during the period. The clashes and connections between the Christian and Ottoman spheres were centered on warfare, espionage, information-gathering, diplomacy, trade, employment, slavery, and other forms of antagonism or collaboration. Malcolm, Senior Research Fellow at All Souls College, Oxford, alternates his point of view from a wide angle focusing on the Mediterranean Basin over the course of the second half of the 16th century to a narrow angle that focuses on two intertwined Albanian families known as the Brunis and the Brutis.

Over two generations the members of these families fulfilled all of the functions listed in the book’s subtitle, and they did so for family, for religion, for reasons of state, for empire, and many others. In general, the prominence and wide distribution of Albanians in the Balkans made them especially capable of crossing cultural divides and this made them valuable to their Western employers. The Bruni family, in particular, also happened to have been related to one of the most of powerful viziers in the Ottoman Empire.

Malcolm shows that identities for early modern peoples in the Ottoman borderlands and their neighboring domains were indeterminate, flexible, and negotiable. They were made and re-made as circumstances required. The Brunis and Brutis were examples of “cultural amphibians” capable of channeling their talent for language, diplomacy, administration, and leadership into the wider European cultural life of the 16th century. They moved with stealth along a chain of distinct but interlocking cultures where national, linguistic, and religious identities could be inhabited, stretched out, and discarded as the ground shifted continually beneath them. Today the Adriatic city of Ulcinj, for example, is part of Montenegro and populated mostly by Albanians. But over the course of two millennia, the settlement was linked culturally or administratively with the Illyrians, the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, Slavic authority, Venetian rule, and then the Ottoman Empire after 1571.

Malcolm does not provide directions on how these events may be read in light of any present-day geopolitical issues, but the theme should feel familiar enough to the modern cosmopolitan reader to inspire speculation. His subjects are products of not one, but several national histories. They were moved by a mixture of motivations — sometimes as principled allegiants in clashes arising out of religious zeal, and sometimes as leaders or agents in conflicts with simple expansionary objectives. But there’s also a dramatic and ordinary human dimension to their actions and we are reminded that individuals at all times — whatever the prevailing structures that govern their lives — are also moved by ambition, friendship, loyalty, adventure, and rivalry. Their conflicts are personal and political as well as ideological and economic.

Bartolomeo Bruti, for example, was a Catholic who worked as the minister of an Ottoman vassal state, thereby technically working with the Ottomans as well as against them. His family was connected by language and by history to Ottoman territories and it gave them an ability to see things “from something more like an Ottoman perspective”. Similarly, Giovanni Bruni’s choices were rooted in experiences derived from his own complicated identity. In 1551 Bruni became the Archbishop of Bar (now part of Montenegro, then in Venetian territory), and in his appearance at the Council of Trent he worked through issues that had bearing on the Greek and Serbian Orthodox subjects of Venice; he spoke to the challenges of overseeing a diocese that was partly in Ottoman territory; and he deliberated on matters that would potentially stir the peoples of Crete, Corfu, and Cyprus.

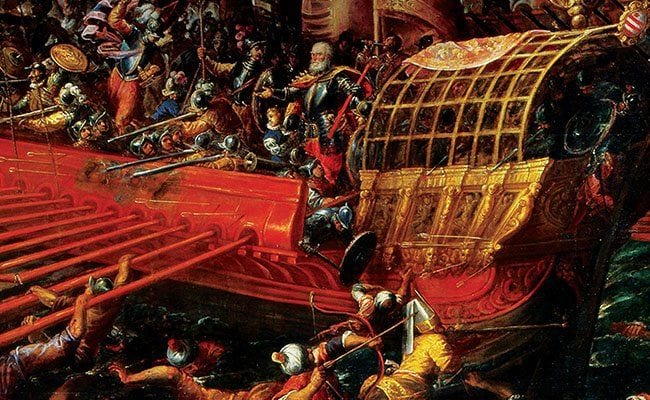

There are many moments that show how Bruni, his family, the West, and the East appeared tangled together. One such small moment was a gift from Bruni to Pope Pius V of three horses that were purchased in Ottoman territory by Giovanni’s brother, Serafino, and delivered directly to the Pope by his nephew, Matteo. A later more brutal instance of such convergence took place in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 when Bruni met his death as a slave on an Ottoman galley — not at the hands of the Ottomans, but by those of Spanish Christian soldiers who refused to believe him when he identified himself as an Archbishop. “[If] only Giovanni Bruni had survived, he could have been reunited almost immediately with his brother”, Malcolm writes, “in a reunion that would have made a novelistic scene worthy of Cervantes.”

The historical methodology employed here for reconstructing moments in almost pointillistic detail is called microhistory. The ability to shift between wide and narrow contexts and to articulate connections between them, in this instance, is made possible by two feats of historical labor. The first feat is the range and sheer volume of sources corralled by Malcolm. He has consulted 39 archives in Europe, including the Vatican, and in areas that were known in the early modern period as “Rumeli” — “country of the Romans” in Ottoman Turkish — the Balkans in this context, which for centuries was administered from out of the Ottoman Empire.

The second feat is the mastery of languages required to meaningfully assess this array of sources — not two or three languages, but actually at least a dozen of them, many of which are in different language families. This is an area where Malcolm is exceptional among English-language historians. His histories of Bosnia and Kosovo, published in 1994 and 1998, respectively, are exhaustive works in which national myths and narratives are scrutinized through their appearance in primary and secondary sources unearthed in a torrent of languages — 20 of them, in fact — many of which are translated by Malcolm and mapped out in his bibliography.

To add to this portrait from a personal point of view, I will say that I became familiar with Malcolm through his work on Thomas Hobbes and my encounters with his Correspondence of Thomas Hobbes (1994) and Aspects of Hobbes (2002) were key moments in the course of my own PhD. Now Sir Noel — knighted in 2014 and senior researcher at All Souls College, Oxford — is perhaps the world’s leading authority on Thomas Hobbes, and I have no problem calling him one of the world’s greatest English-language historians. He’s certainly one of the few scholars qualified to unpick the bewildering tangle of social and linguistic threads that run through the early modern Ottoman frontier.

Agents of Empire is an important book for at least three reasons. The first is that the stories and personalities described in it are valuable not only for their intrinsic interest but also because they exemplify Malcolm’s skill, in the microhistory tradition, for conjuring humanity and drama from out of the archives and reconstructing the lived experiences, agency, and choices faced by individuals who have effectively been obscured by time and posterity. The second is that it is the work of an historian with a salutary reminder — pace all political scientists, sociologists, and others who work with structures, systems, and abstract categories – to always keep sight of the humble human being, moved by impersonal forces as well as by their individual passions and imperfections.

The third is that, in Agents of Empire, we encounter complex individuals who appear resistant to the simple categories, generalizations, or identifications that we, in retrospect, may be inclined to assign them. There is a modern complexion to these individuals — they were people in motion and they were never quite at home.