Recently, the film Innocence of Muslims joined a long list of dubious cultural products that had in common one thing: Islamophobia in the guise of “free speech”. According to many of the media reports that were widely circulated, the protests by Muslims in various countries was a direct result of the film itself; as such, the protests were to be understood only as a response to the film, and thus a clear sign of the irrationality of Muslim belief. (See, for example, Newsweek’s “Muslim Rage” cover, accompanied by an equally-dispiriting and small-minded article by the Western world’s favourite anti-Muslim, Ayaan Hirsi Ali.) Protests in Libya that resulted in the death of the American ambassador in Benghazi were also attributed as a reaction to the movie and the movie alone, as though Libya hadn’t just undergone immense political shifts in the last year, as though geopolitical factors were not a (bigger, more significant part) of the story.

Through it all, much of the rhetoric from both liberal and conservative Western media outlets and pundits revolved around the idea of Muslims as irrational and incapable of telling fantasy from reality. This idea of free speech and creative and artistic expression (though one would argue about the applicability of “creative” in a product as unimaginative as Innocence of Muslims) is consistently evoked as an idea that grew out of a particularly Western tradition of civilisation; ideals that were founded upon the rationalism of the Western Enlightenment. It’s a narrative that’s been used constantly—to cite two examples of recent international focus, for example: the Danish cartoons, and the Salman Rushdie issues—and it’s a narrative that glosses over the racism, xenophobia, and rapidly-growing notions of Islamophobia that colour these works of art and cultural commodities, works that supposedly uphold values of free speech and free creative expression.

Mainstream, popular discussions about Muslim belief and art tend to be reductive, ahistorical, and removed from particular specificities and contexts that arise from geographical location, class, gender, race, and nationality. The War on Terror (the war of terror) has only heightened and magnified Islamophobia across the globe, and this insidious anti-Muslim rhetoric seeps into discussions outside of the directly political. Framed as, “Why do they hate us?”, Muslim objection to anti-Muslim art is thus taken to be an assault on a particular form of (superior) civilisation, particularly Euro-American centric, and in crafting this narrative, Muslim and Islamic engagement with art is conveniently disappeared. As such, Jamal J. Elias’ Aisha’s Cushion: Religious Art, Perception, and Practice in Islam arrives at the right time and is an extensive, finely-detailed work of research that seeks to upend predictable, simplistic beliefs and assumptions about the role of Islam in artistic creation and reception.

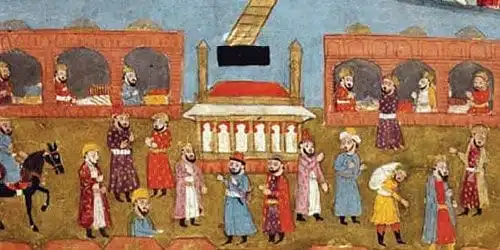

Elias is the Chair of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, and he brings a wide depth of knowledge and instruction to his writing. Written before Innocence of Muslims was anywhere close to hitting the public sphere, Elias uses the Danish cartoons and the Taliban’s destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan as his contemporary cultural starting point before exploring the ideas, thoughts, and philosophies that have shaped, moulded, and deconstructed Islamic ideas about the role of art in both religious society and society at large. As Elias states early on in his prologue, the complex factors underlying how images are seen and understood within the context of Islam, such as the depiction of the prophet Muhammad in the case of the Danish cartoons or even in South Park, is that “the presence of the image itself was not objectionable; rather, the image’s status was determined both by its content and specific context in which it appeared.”

Elias’ approach is layered as well as chronological; he discusses and compares issues of representation, and forms of icon use and idol-worship and attendant beliefs about aniconism through the prism of not only Islam, but Hinduism, Buddhism, and Christianity, as well as brief forays into Judaism. Anthropology and art history, as well as technique, form the basis of the book’s early chapters on concerns around mimesis and representation:

“Images and their resemblance exist in a habitus in which the purposes of those responsible for the images as well as the understandings of their viewers and receivers determine how the images function as representations of prototypes as well as concepts. Religious images might fulfill a multitude of functions including remembrance, honor, instruction, and intercession, where the last is either for protection in a prophylactic or talismanic sense, or is salvific. In light of this spectrum of functions, when the considering the representational power of images, we would do well not to overemphasize their formal mimetic qualities and recall Gadamer’s statement that a religious image is not a ‘copy of a copied being, but is in ontological communion with what is copied.’ It is the affective relationships, rather any formal mimetic visual qualities, that are ultimate determinants of the value of a religious image.”

Elias’ approach throughout Aisha’s Cushion is not merely to link anthropology and religion with art history; rather, it is to show how these approaches are embedded within each other, and how they produce and dissemble the discourse on aesthetics and the efficaciousness of images used for religious purposes. His meticulous research shows us that the limits of present-day narratives of “the clash of civilisations” exist precisely because history is often erased from these discussions or manipulated entirely for political ends, and outrage over ruined icons or images tend to circulate within a commodified news cycle that emphasises spectacle and profits.

When people rushed to condemn the Taliban’s destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, not many were interested in knowing the hows and the whys behind that particular act. Understanding the context is not to do the opposite and “support” the destruction, however, but to understand the vast political, cultural, and historical factors behind every act of commemoration or destruction. Furthermore, Elias doesn’t discuss this, but historical/religious edifices and buildings with artistic or cultural value are torn apart regularly in the interest of capital and profits—“development”, as it were—and the outrage, or shock, is often minimal or muted. The remaking of the world is often seen as useful or progressive, or barbaric and medieval, depending on who does it and on who gets to shape and mould the ensuing discussion.

For the reader interested in art history, perception, and history, Aisha’s Cushion can sometimes be overwhelming, particularly when Elias focuses on detailed narratives of alchemy and optical theories of perception. Other chapters on dreams and prophecies, or representation and the role of writing and literacy in producing classes, and thus, power structures, are illuminating and compelling, particular in this age of “media literacy”, where expertise comes to us via academics, journalists, and writers, whose opinions and discussions on how media is used and received by consumers that tend to trump actual affective experiences of the users themselves, particularly if they’re young, female, or Elias reminds us, religious. To that end, however, it’s worth noting that this book considers and engages with theories and philosophies of aesthetics and religious worship as seen by men, be it Ibn al-Haytham and Ibn Sina, or Baudrillard and Plato. Aside from the Aisha of the book’s title, gender gets a specific mention in one paragraph:

“The majority of the population in classical and medieval Islamic society would belong to the class and sex in which literacy was rarest, yet not only did illiterate women function in fulfilling ways within a world where scriptural literacy was valued highly, but anecdotes about the connection between female illiteracy and religious devotion ostensibly underscore the view that literacy has no correlation with virtue.”

Perhaps this is one reason why there is a paucity of records on medieval or early modern thought on aesthetics and art by women, but one does wonder about the absence of contemporary women art theorists, theologians, and philosophers—their perspective would have been particularly valuable in the chapters that discuss beauty and virtue from Plato onward, or as shown above, in the sections that explore literacy and virtue and power. Though Elias does give us the example of one anecdote following the passage above, the venerated, beautiful female object whose illiteracy renders her necessarily silent in historical archives and records but who is nonetheless held up as virtuous and pious because of her exhibition of a proper form religious devotion is surely an interesting subject, and one whose omission necessarily shapes the phallocentric discourse of both religion and art.

Instances of iconoclasm, or strong objections to depictions of the prophet Muhammad, underscore the power that resides in a piece of art, and the attempts are rarely made to remove them completely (as is often assumed) as to neutralise their power, as Finbarr Barry Flood points out in his essay, “Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum”. This is an erasure of value that Elias finds problematic, or troubling, in Western theories of aesthetics, which he calls “a form of detached contemplation completely free from any concern with didactic, ritual, or other purposes.” Decontextualisation is the only way with which to approach art these days, a sort of tyranny of objective reasoning: “It is the tearing of an object from its context that allows for objects of historical significance to be neutered and seen purely as ‘art.’” The decontextualisation of art and its transformation into an exhibit, as is the case of museum and gallery displays, is its own kind of hegemony that follows in the long tradition of Western colonialism and imperialism, something that Flood teases out in “Between Cult and Culture”:

“It has been suggested that certain acts of iconoclasm directed against Western museums represent “protests against exclusion from the cultural ‘party game’ in which only a minority of society participates.” Similarly, Taliban iconoclasm can be understood as constituting a form of protest against exclusion from an international community in which the de facto hegemony of the elite nations is obscured by the rhetoric of universal values.”

In light of people saying they “wouldn’t be upset” if the face of Vladimir Umanets, defacer of a Mark Rothko mural, “accidentally met with a baseball bat”, it’s interesting and revealing to consider reactions to Muslim objection to anti-Muslim “art”, be it badly-produced films or badly-drawn cartoons. Muslim objection is seen as unreasonable rage, always out-of-time and out-of-place. Rage is acceptable, unless it’s not. It all depends on who’s expressing the rage.

While Aisha’s Cushion is expansive and edifying, particularly for people with very little knowledge about art history and religion, it’s also a plunge into deep waters for the casual reader, particularly since Elias’ style is resolutely dry and factual. Furthermore, certain lingering questions remain: that of the role of neoliberal politics in the reception of both art and its “destruction” (as Flood points out, the Taliban geared their act towards a global audience of “the Internet age”, and so did the makers of Innocence of Muslims), as well as that of the dangers of the “aestheticization of politics” versus the need to “politicize art”, as Walter Benjamin put it in his 1936 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”. In the contemporary context, however, where politics is spectacle, the difference isn’t quite so clear. While Elias does an admirable job of surveying the past, the future, as ever, appears murky.