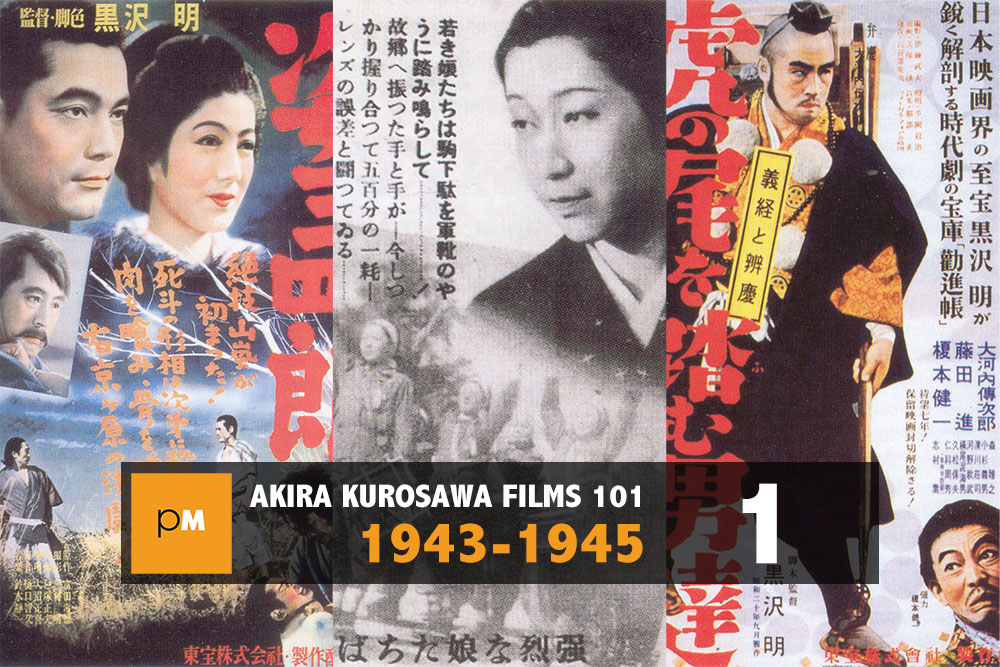

The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail (1945)

Often regarded as the most difficult of Kurosawa’s films for non-Japanese viewers to appreciate, The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail offers unexpected pleasures for those willing to do a bit of exploration of the cultural and historical background for the film.

The film is a revision of the famous Kabuki play Kanjincho, which was itself based on the Nō play Ataka. All are loosely based on historical events, the pursuit by the late 12th Century shogun Yoritomo of his popular half-brother Yoshitsune. After being chased for four years, Yoshitsune killed himself along with his wife and children. Yoshitsune has ever since been celebrated in Japan as the quintessential tragic hero. Although Kurosawa preferred Noh to Kabuki theater (his later films Throne of Blood and Ran would display considerable Nō influence), The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail is more in the Kabuki style.

Kurosawa focused on one of the more traditional incidents in Yoshitsune’s story, the attempt by his guards disguised as Buddhist monks to sneak Yoshitsune past a checkpoint held by those faithful to Yoritomo.

The key event in the story is the game of wits at the checkpoint between Yoshitsune’s bodyguard Benkei and Lord Togashi, the commander of the checkpoint. The climax of the film occurs when Benkei, who has told Togashi that they are Buddhist monks traveling to distant areas soliciting donations for the rebuilding of their temple, is challenged by Togashi to read the prospectus. Since the document does not exist, Benkei has to bluff by unfurling a blank scroll and successfully adlibbing its contents.

The tensest moment occurs when Togashi’s aide accuses their porter of being Yoshitsune in disguise (which he is). Benkei instantly charges in and begins beating the porter, accusing him of shirking. Togashi declares to all that obviously the porter could not be Yoshitsune because no one would beat their lord in such a fashion.

Kurosawa makes two interesting changes to the story, both of them controversial. One is that he makes Togashi far more intelligent than he is usually portrayed. In his version, Togashi (played by Susumu Fujita, who had the starring role in Kurosawa’s first film, Sanshiro Sugata) is not duped by Benkei, but apparently respects his devotion to his master as well as his skill in answering his questions (such as his request that Benkei read the prospectus). Togashi, therefore, becomes almost an accomplice in Yoshitsune’s escape.

The second major change is the inclusion of a comic character of Kurosawa’s own creation. Kenichi Enomoto, whose antics and physical mannerisms will put many people in mind of Jerry Lewis in the 1950s, is added as porter whose sole purpose is to provide comic relief, though doubtless, some will debate to the degree to which his presence is relieving. Enomoto is not a subtle performer and his performance is best described as excessive. Many viewers of the film like Kurosawa’s twist on Togashi’s character even as they regret Enomoto’s porter.

The film enjoyed a complex history from creation to eventual release. From 1943 until 1945 Kurosawa struggled with the censors of the military government, who placed considerable limitations on the kinds of stories that could be told in films. Toho had authorized a project entitled The Lifted Spear, with the end of the film to show the Battle of Okehazama of 1560, in which Nobunaga, a feudal warlord who began the process of Japanese unification, defeated his rival Yoshimoto (in 1980 he would finally show Nobunaga winning a battle when he filmed the Battle of Nagashino in Kagemusha). The film was to star Denjiro Okochi (who had headlined Sanshiro Sugata as the title character’s teacher) and Enomoto, the pair two of the biggest stars in the Japanese film industry. But because the climactic battle scene required a large number of horses and the war effort had taken nearly all of the horses in Japan, making the original film was impossible.

Kurosawa quickly reworked the project, retaining the two lead actors, but choosing instead the story outlined above. Before much work was completed, the Japanese surrendered, ending WW II. Filming commenced under the most stringent circumstances, with material resources limiting set design. Kurosawa got around this by working with a small studio set that was reworked to become different rural locations in addition to the checkpoint where the main encounter between Benkei and Togashi. (There are some fascinating home movies taken by American servicemen in the first wave of the occupation visiting the set, with the actors all in full costume and high spirits; excerpts of which can be seen in the Adam Low documentary Kurosawa.)

In general, the American occupation censors were far less restrictive than the Japanese military censors had been (while some of these films during the occupation had details changed upon request, Kurosawa frequently just ignored the censorship rules, such as the request to not show signs in English). In a final act of revenge by the Japanese military censors, they left Kurosawa’s film off the list of films already in production, causing this to be labeled as an illegal production. As a result, the film was banned from distribution. The ban was lifted in 1948, but Toho chose not to release the film until 1952, in the wake of the enormous positive publicity attending to Kurosawa in the wake of Rashomon winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail may not be among Kurosawa’s most accessible films to Western viewers, but for those willing to take the trouble to understand its nuances, it is one of his more interesting early films. — Robert Moore

WATCH: The Criterion Channel

+ + +

This article was originally published on 10 October 2010.