Four silent films with new musical scores plus one talkie comprise Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray of Hitchcock British International Pictures Collection, a lovely gift for Alfred Hitchcock buffs containing films he made for producer John Maxwell’s British International Pictures in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

The silents demonstrate what was already clear in Hitchcock’s 1927 hit

The Lodger, that he was not only a master of visual storytelling but confidently made silents as though they had sound effects. Time and again, the films present the image of something making noise or people responding to a noise, creating the illusion of said noise in the viewer’s brain.

The second striking consistency in Hitchcock’s silents concerns the style he adopts for dialogue in alternating closeups. In most movies, such moments are conveyed either in over-the-shoulder shots or in three-quarter profiles with one person looking offscreen left and the other offscreen right so that their eyelines match. In his silents, Hitchcock frequently presents his actors emoting directly, we might say nakedly, into the camera, which adopts the alternating subjectivity of one person or another.

We gaze directly into their shiny eyes in a technique of delicate intimacy. Once or twice, Hitchcock even has someone gaze into the camera without any other character in the room. This kind of gesture would be overwhelming in a talkie, as when Stephen Roberts uses it for the most alarming and confrontational moments in

The Story of Temple Drake (1933), but it works very effectively in silents. In her commentary on The Manxman, Farran Smith Nehme quotes Dave Kehr making similar observations on the technique, because great minds run in the same channel.

Drain by Semevent (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

The Ring (1927)

Written and directed by Hitchcock as his immediate follow-up to The Lodger, is a boxing picture. As critic Nick Pinkerton asserts convincingly in his commentary, the concept was probably inspired by a real-life high-profile boxing match in London that year that generated oodles of publicity, and whose referee plays himself in this film. The story may have been inspired by a German film greatly admired by Hitchcock that had been a hit, E.A. Dupont’s Variety (1925), about jealousy in a romantic triangle.

Hitchcock’s story focuses on a big dumb lug named One-Round Jack (former boxer Carl Brisson). We’re left to speculate (as Pinkerton suggests) whether this nickname also indicates why his girlfriend seems sexually unsatisfied. Said gum-chewing girlfriend is Mabel (Lillian Hall-Davis), and please note that she’s not a “Hitchcock blonde”. She sells tickets at the carnival tent run by a scowling large-mouthed barker (Gordon Harker) as Jack takes on all comers inside.

Aussie boxing champ Bob Corby (Ian Hunter) and his manager (Forrester Harvey) scout the proceedings, although neither the viewers nor the other characters realize it until after Bob has stepped into the ring and knocked Jack out. Even while Bob was just standing in the crowd, Mabel caught his eye and flirted shamelessly.

Once Bob proves himself the better fighter and starts grooming Jack as a future champion whose name rises higher on the posters, Mabel more or less openly hangs out with Bob. Jack stews and makes excuses for her.

Jack and Mabel have gotten married in a comical scene with much interplay with “the ring”, and she’s received a snakelike bracelet from Bob that adorns her arm. These recurring visual motifs are played for comedy and drama as Hitchcock seamlessly orchestrates scenes by cutting between telling details. The boxing matches, for example, are presented in a manner to tease the audience with what’s shown and what’s withheld until the final big match that Martin Scorsese admits influenced Raging Bull (1980).

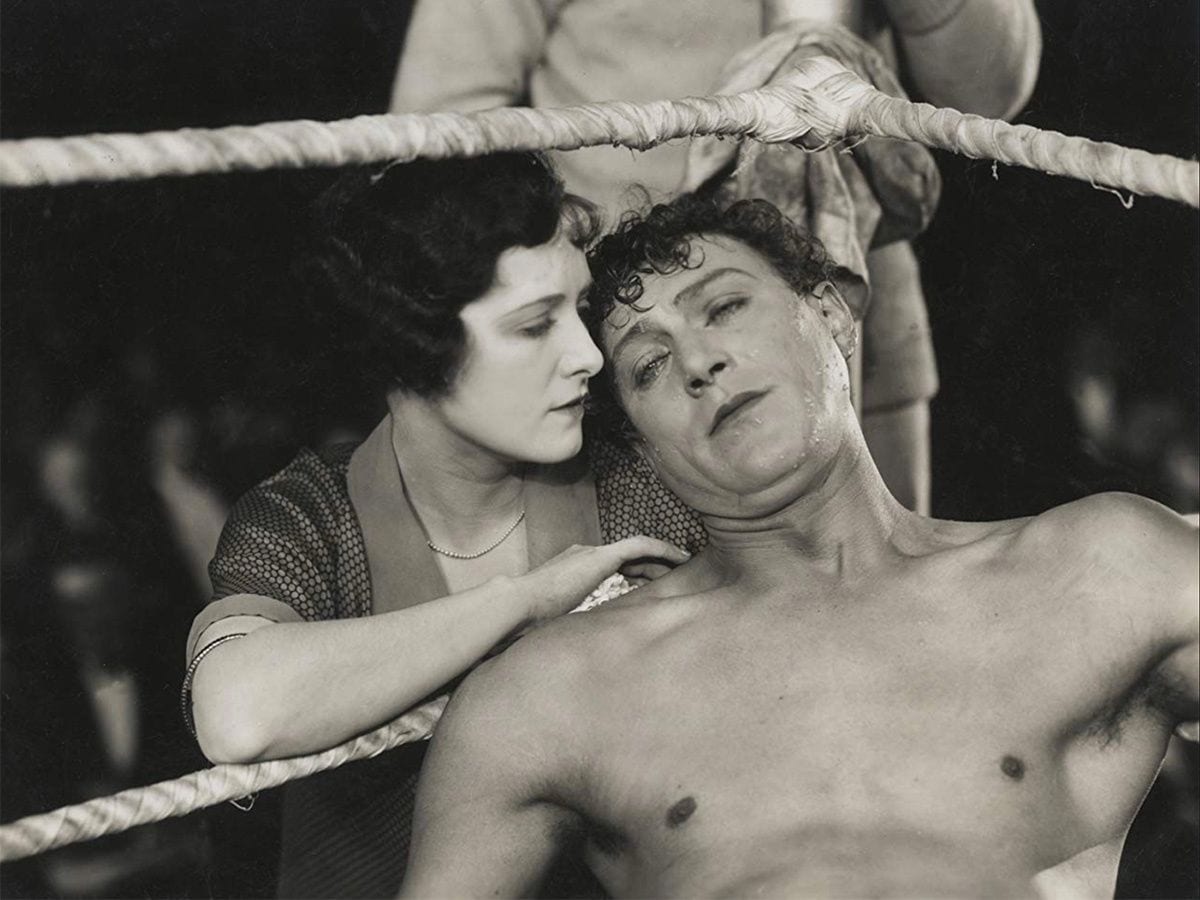

Lillian Hall-Davis and Carl Brisson in The Ring (1927) [© Courtesy: Rialto Pictures/BFI / IMDB]

One curious element in The Ring is the continuous presence of black characters while making the point that although they exist in this milieu, they’re not respected. This point is summarized in an emblematic early scene where a black man sits in a dunking booth. Instead of throwing balls at the target, two mischievous boys throw eggs at him. The crowd laughs, with a prominent close-up of a laughing policeman.

The stand’s proprietor (played by Hitchcock!) complains and upbraids the bobby, prodding him to do his job and chase the boys away. This scene offers early evidence of the director’s famous dislike of the police

One of the Jack’s trio of chorus-like buddies is black, and there are no accidents in casting. Yet Jack shows no reaction when the manager, in a film where Hitchcock avoided title cards as much as possible, gratuitously tells him that his career will improve if he can beat “the nigger” in his next fight. Nick Pinkerton’s commentary observes that racial competition was built into the fight game (“the great white hope” etc.) but he finds it a stretch to believe Hitchcock was offering a deliberate social commentary.

I find this startling slur and its casual acceptance credible and consistent with how Hitchcock presents a low-class culture of disrespect. He will comment on it again in Lifeboat (1944) through the character played by Canada Lee, whom Pinkerton points out had been a boxer.

The Farmer’s Wife (1928)

Lillian Hall-Davis reappears in a completely different role as the heroine of The Farmer’s Wife (1928), a comedy of rural life and marriage based on a popular play by Eden Philpotts. Hitchcock’s faithful and detailed filming of a hit play, rendering it cinematic with everything from fancy dissolves to outdoor scenes to a multitude of vivid closeups, makes it easy to believe that the film presents this material more entertainingly than the stage.

The story focuses on Samuel Sweetland (Jameson Thomas), a bumpkin-ish gentleman farmer whose wife dies in the opening scene. With her last words, the dying woman entrusts housekeeper Araminta (Hall-Davis) to wash and dry the master’s pants, thus implicitly passing the widower on to the servant. Her wish is promptly realized in a montage presenting these worn and bulky under-drawers in a variety of settings.

What might be seen as erotic is really workaday and comic. It’s a perfect example — along with the sweeping establishing shots of bucolic landscape that open the picture until we arrive at the closeup of Sweetland gazing out the window — of how the material is transposed from stage to film.

When Sweetland decides to marry again after his daughter’s wedding, he goes shopping among the local hopefuls and first picks the sensible widow (musical comedy star Louie Pounds) who has no intention of giving up her independence. He goes through other possibilities of various demeanor (Maud Gill, Olga Slade, Ruth Maitland), always coming down a peg in his manly pride and self-assessment as a catch. The audience knows from the start that, according to the old saw, what he’s looking for is right there at home.

It takes two charming hours of the movie before he figures it out. The long comic highlight is a tea party, meticulously constructed with over a dozen characters, paced to alternate intimate interludes with crowd scenes, and combining character observation with full slapstick hilarity. Unfortunately, a scene seems to be missing from the fox hunt sequence where he makes his last unsuccessful proposal.

French movie poster for The Farmer’s Wife (modified) (IMDB)

What links this film thematically to The Ring is the public sexual humiliation of the hero, who in this case must be chastised of his arrogance before he’s fit to see sense about whom he should marry. This theme is also crucial to Downhill (1927), which Hitchcock made for Gainsborough Pictures right before The Ring but was released right after; it can be seen as a bonus on the Criterion release of The Lodger. This sexual humiliation will resurface in The Manxman and even as a plot device in The Skin Game.

In The Farmer’s Wife, Gordon Harker, who played the sour scowling barker in The Ring, plays sour scowling servant Churdles Ash, who observes all with jaundiced eye. The initially mild comedy of his fear of losing his pants, in echo of the early montage of the farmer’s pants, pays off big when we’re least expecting it and echoes the theme of male humiliation. He himself articulates the idea that the farmer’s failure makes all men look bad.

Prolific character actor Gibb McLaughlin plays another comic trope as a local boring hayseed who drives everyone to distraction. He and all the other caricatures fall into an English tradition of class and rural comedy handled with aplomb.

As with all the other films in this set, the photography is by Jack E. Cox. We see several lilting dolly shots as the camera follows behind one character or another. The beautiful sets are courtesy of art director C. Wilfred Arnold, who did all the silents here. The script is by another of Hitchcock’s consistent collaborators at this time, Elliot Stannard. He’s credited on the other silents except The Ring and he might have worked without credit on that one.

Champagne (1928)

The comedy shifts from country matters to glittering urbanity in Champagne (1928). But wait. Actually, another sparkling comedy came first, an adaptation of Noel Coward’s play Easy Virtue (1928) for Gainsborough Pictures. Perhaps it’s best described as a witty melodrama, since it involves a divorce scandal. Champagne is wonderful. One of Hitchcock’s shortest and swiftest silents and very stylish. Not being a British International Picture, it’s absent from the set, and the restored version is currently on disc in France only. We hope for its Region 1 release.

While I’d say Easy Virtue is really a champagne-ier movie than Champagne, the latter is certainly giddy. Producer John Maxwell and story editor Walter C. Mycroft conceived it as a vehicle for Betty Balfour, probably England’s biggest silent female star. She’d become famous as Squibs, a Cockney flower girl in a rags-to-riches series of comedies. She left her former studio for British International as a way of branching out. Historians indicate that Hitchcock felt uninterested and frustrated with the assignment.

We’re introduced to spoiled debutante Betty (Betty Balfour) as she lands a private plane in the ocean by a luxury liner and steps into a lifeboat in her aviatrix leathers before the plane sinks. It’s a madcap stunt pulled to hook up with her unnamed sleepy-eyed boyfriend (Jean Bradin), who’s tuxed and pomaded to within an inch of his life.

On the ship she meets an oily lounge lizard (Ferdinand von Alten) and argues pointlessly with the boyfriend, which is something she’ll do for the rest of a picture that Hitchcock himself described as having no story. According to the commentary by Faran Smith Nehme, much of the film’s scenario was invented as it went along, and that feels likely during protracted antics that never lead anywhere while keeping the lovers apart until the final clinch. If we retrospectively analyze what we learn of the father’s manipulations, nothing in the plot makes the slightest sense.

As Betty lounges in Paris with empty-headed society friends, at one point spoofing Balfour’s “British Mary Pickford” image, the wisp of a plot is triggered when her father (Harker again) announces that their fortune is lost on Wall Street, which would happen to a lot more people after the 1929 crash, although nobody knew that yet.

Betty Balfour in Champagne (1928) [© Courtesy: Rialto Pictures/BFI / IMDB]

By the way, he’s an American millionaire who owns a champagne business during Prohibition, a paradox that Nehme points out as being noticed by nobody at the time. If he’s a bootlegger, his business clearly wouldn’t be on the Stock Exchange. Does he do all his business abroad?

Anyway, Betty promptly gets a job in a colossal restaurant/nightclub with balcony and upstairs party rooms, where she supposedly sells flowers in a ridiculous get-up. She runs into the lizard (again) and argues with her boyfriend (again). The story is at its most strained and tiresome here, although the movie consistently looks grand and indulges several playful visual gestures. For example, a couple of shots are staged through the bottom of a champagne glass; should we call it a shot glass? There’s even a fantasy sequence in which Betty imagines herself into a more Expressionist melodrama, as though that’s where Hitchcock would rather be.

This film includes two minor black characters in startling contrast. The first is a cowering comic-relief messenger who flees the wrath of Betty’s father. The next is a refreshingly non-stereotypical bartender who even gets a line of dialogue, referring to a cocktail as a maiden’s prayer.

Nehme points out connections with later Hitchcock films, such as the throwaway part of a daunting woman servant visually coded as a lesbian. (The hale and hearty fox-hunting widow in

The Farmer’s Wife is similarly coded, though she’s jolly and self-confident rather than sinister.) In the end, Nehme finds Balfour’s vivacious presence and the mise-en-scène attractive enough to prefer Champagne over The Farmer’s Wife. Francois Truffaut was also delighted by various gags in Champagne.

In our opinion, the crucial difference between these comedies is that

The Farmer’s Wife is funny, and its hero’s reformation (which never occurs with Betty) is touching as he learns to shed his pretensions. We agree with the assessment by the British Film Institute’s Mark Duguid that The Farmer’s Wife is “perhaps the most warm-hearted of all Hitchcock’s films”.

As for

Champagne, Nehme explains that in this film’s restoration, the British Film Institute discovered that the original “A” negative doesn’t exist. This print comes from the “B” negative, meaning it was pieced together from alternate takes not necessarily representing the version that played in English theatres. So, although the film survives in some form, we’ll never really know its preferred version. Still, it does look good even as a shaggy debutante trifle, and we’re glad for what we’ve got.

The Manxman (1928)

Hitchcock’s last pure silent feature is set on the independently governed Isle of Man (where men are “Manxmen”). But it’s shot mostly in equally picturesque Cornwall after a few scenes on the Isle. The Manxman, shot in 1928 but shelved until 1929 after the release of the silent and talkie versions of Blackmail, is a powerful and frequently gorgeous melodrama from an 1894 bestseller by Hall Caine, a phenomenally popular novelist who was still alive and living on the Isle of Man.

The story’s romantic triangle includes possibly the most tender male friendship in Hitchcock’s output. It’s between simple sailor Pete (Carl Brisson, the equally naïve hero of The Ring) and higher-class buddy Phil (Malcolm Keen, the wrong-headed cop in The Lodger). The object of their love is fun-loving barkeeper’s daughter Kate (Anny Ondra, heroine of Blackmail), who loves Phil but has rashly promised herself to Pete.

When everyone briefly thinks Pete is dead, Phil and Kate deepen their relationship. Until she becomes pregnant, although she may not realize it until after Pete suddenly shows up and marries her. The marriage is torture for her, despite Pete’s doting good nature. She will finally rebel with a startling strength of mind that might head the tale into tragedy, but we’ll not say for sure. Nehme’s commentary discusses that the play version used two different happier endings while the film is closer to the novel; we’ll say only that the film’s ending is mature and ambiguous and all the more emotional for it.

Nehme points out the unusual nature in Hitchcock’s output of the scenes where the men await the baby’s birth, and she observes that Hitchcock made the film just after the birth of his daughter Patricia. The false father’s emotions feel outsized yet sincere and convincing and make a striking contrast with the worried demeanor of the true father.

Although modern audiences are used to a quicker pace (but not always), the slow build-up to the climactic confrontations works in The Manxman‘s favor, as do everyone’s performances, the vivid atmosphere and the sets. Future director Michael Powell was employed as a still photographer on this project, and we must wonder if the experience of visiting a self-contained fishing island of proud locals influenced his decision to make for the Outer Hebrides in The Edge of the World (1937).

Carl Brisson, Malcolm Keen, and Anny Ondra in The Manxman (1929) [© Courtesy: Rialto Pictures/BFI / IMDB]

The Skin Game (1931)

The set’s only talkie is The Skin Game (1931), a moralistic tragedy based on John Galsworthy’s 1920 play about a feud between two families who represent different social classes.

The Hillcrists are gentry consisting of a decent old gouty duffer (C.V. France), his take-charge wife (Helen Haye) and a horse-riding daughter (Jill Esmond) who stands around commenting on how everything’s so frightfully beastly and common, dash it. The appropriately named Hornblower (Edmund Gwenn) is a self-made nouveau riche factory owner from a working-class background; in other words, a vulgar upstart, and also the future. Haye and Gwenn were reprising their roles from a 1921 film version.

The troubles begin when Hornblower evicts two of Hillcrist’s old tenants for the sake of his “progress”, thus breaking his word and proving “he’s not a gentleman”. Events escalate into a land-auction and blackmail over the sexual past of his daughter-in-law Chloe (well-played by Phyllis Konstam, the gossipy neighbor in the silent version of Blackmail), who’s married to Charles (Johnny Longden, the compromised cop in Blackmail). Everyone behaves dishonorably and unpleasantly, getting their hands dirty over snobbery, competition, and vindictiveness.

Unfortunately, this film offers an example of what people mean by saying that early talkies are often creaky and stagebound. Hitchcock avoided that on Blackmail and Murder! (1930), so it must measure the difference between personally engaging projects and assignments that left him indifferent.

Phyllis Konstam in The Skin Game (1931) (IMDB)

Hitchcock does move the camera, often desultorily, during the endless dialogues of high-class twitter and working-class bluster. He cuts loose during the auction, when the camera adopts the auctioneer’s POV and swings sharply around the crowd looking for bidders. The auctioneer is played by Edward Chapman, a long-standing British comic actor. During that scene, the director finds a reason to use frantic superimpositions to convey the panic of a guilty woman. As the camera adopts her POV, ghostly faces swim forward as if it’s a 3D movie. This part of the plot generates suspense, so we see the director become more engaged in his visual language.

There’s more suspense during a climactic scene when Chloe hides behind a curtain and Hitchcock’s cutting and staging become more active. Another subjective moment has Hillcrest imagining the countryside being replaced by a factory as a woman chatters inaudibly behind the image. Since the material didn’t much fire up its director’s interest, the film must rely on its actors and the swiftness of its 80-minute plot to get itself across, with only those few flourishes mentioned.

Early talkies often set the stage with vigorous scenes that were shot silent, without regard to recording sound, and had post-dubbed sounds instead. We see an example here in a public quarrel on the street between a shepherd and one of Hornblower’s lorry drivers. We also see bucolic stock footage that looks lifted from the opening of The Farmer’s Wife.

Hitchcock utterly dismisses this movie in the excerpts from the Hitchcock/Truffaut interviews included as the only bonus aside from commentaries on three films. Certainly The Skin Game is nobody’s idea of essential Hitchcock. Perhaps the other films discussed here aren’t either. But the others come across as beautiful silent films, thoroughly professional and visually engaging, and we can enjoy a festival of cross-references and foreshadows with more well-known Hitchcock pictures.

The filmmaker’s British International period was crucial to his career, and it’s a pleasure to have these films. Everyone with even the slightest interest in Hitchcock – -and isn’t that all of you? — should check it out.

You know what else we need on Blu-ray? Plenty, including the above-named Easy Virtue, the Sean O’Casey drama Juno and the Paycock (1930), the lavish musical Elstree Calling (1930), Benn W. Levy’s Hitchcock-produced murder play Lord Camber’s Ladies (1932), the comedy Rich and Strange (1932), the dazzling (at least in its opening reel) Number Seventeen (1932), and the lavish almost-musical Waltzes from Vienna (1938). And of course, the brilliant Hitchcock suspense of Secret Agent (1936), Sabotage (1936) and Young and Innocent (1937) ought to be shoo-ins for Region 1.

Thanks to the efforts of the British Film Institute, a ton of lovely British silents are floating around, like Norman Walker’s Widecombe Fair (1928), another bucolic British International film scripted by Stannard from a Philpotts novel. This and many others have at least a tangential association to Hitchcock, even if it’s only that he didn’t happen to make them.

If “British Silents You’ve Never Heard Of” doesn’t sound like a sexy package (and it does to me), how about luring the yokels with a title like “All Around Hitchcock: Rediscovering British Cinema”. I’m throwing that out for free. Let’s get cracking!

- The Alfred Hitchcock Story - PopMatters

- The Shower Scene and Hitchcock's Narrative Style in 'Psycho ...

- Why Would Criterion Want Alfred Hitchcock's 'Foreign ...

- Reassigning Power in Alfred Hitchcock's 'Marnie'

- Alfred Hitchcock May Be a Moralist, but He Does Not Moralize ...

- Hitchcock Breaks the Sound Barrier in Blackmail and Murder ...

- Director Spotlight: Alfred Hitchcock - PopMatters

- The Three Faces of Hitchcock - PopMatters

- A Difference of Laughter Between British and American Hitchcock