Narrating ‘Psycho’

“The Opening of the Body”

One of the most important features of contemporary horror is the depiction of explicit graphic violence. Again, Psycho constitutes a first foray into this new tendency. Paradoxically, the famous shower scene is based on showing but without actually showing anything. What Hitchcock does is to create the illusion of showing through editing.

The opening of the body from this moment on will become a sign of the horror film. In Clover’s words:

“For better or worse, the perfection of special effects has made it possible to show maiming and dismemberment in extraordinary credible detail. The horror genres are the natural repositories of such effects; what can be done is done, and slashers, at the bottom of the category, do it most and worst. Thus we see heads squashed and eyes popped out, faces flayed, limbs dismembered, eyes penetrated by needles in close-up, and so on.”

The next step in this evolution is Night of the Living Dead and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. In these films, the opening of the body becomes real. In them, bodies are literally opened, dismembered with a chain saw, or eaten alive.

Hitchcock, as I have been pointing out, is a very innovative director, within the frame of classical narrative cinema. Similarly, Psycho is very innovative, but within the frame of classical horror. Hitchcock is, therefore, a pioneer on opening new paths, but without abandoning the main road.

He went even further with Frenzy (1972). Here, he showed graphic violence. But it was so unbearable that he chose to introduce some humor. The scene with the potatoes is a perfect example of this.

The ultimate example of the depiction of violence but without humor can be found in a film such as Henry, Portrait of a Serial Killer (dir. John McNaughton, 1986). McNaughton shows us one violent murder after the other with the precision of a cold blooded surgeon. There is no emotion, no fun, no laughs at all, just the brutal depiction in a semi-documentary style of the savage atrocities of a serial killer. Hitchcock never did something like that. In Psycho, there is nothing shown, but only suggested. Clover comments on the shower scene:

“Of the forty-odd shots in as many seconds that figure the murder, only a single fleeting one actually shows the body being stabbed. The others present us with a rapid-fire sequence of shots of the knife, of the shower, of Marion’s face, arm, and feet, finally the bloody water as it swirls down the drain and dissolves to the image of a large, still eye. The horror resides less in the actual images than in their summary implication.”

I would argue that the shower scene is the most influential scene in the history of the horror genre. Most horror films after Psycho included one reference or another to this scene. The brutal stabbing, the shot of the hand with the knife, and the dead eye of Marion, are landmarks in the history of the genre.

To show the pervasiveness of Psycho in contemporary horror genre, I would mention an award-winning short named Aftermath (1994). It was shot in Spain by the promising young filmmaker Nacho Cerdá. The film is about what happens after death to a female corpse in an autopsy room. If I have brought it here, it’s because it contains an explicit homage to Psycho, with a shot clearly reminiscent of that of the water flowing into the drain, along with Marion’s blood. I think this shows beyond any doubt the influence Psycho has had and still has in filmmakers around the world.

“Closure of the narrative”

One of the most characteristic features of classical narrative cinema is the closure. Psycho is a starting point for the defiance of that rule too.

At the end of the film, an oscillating movement takes place between the closure and the non-closure of the narrative. The explanation provided by the psychiatrist provides a sort of closure to the narrative. But then, the speech of the ‘Mother’, inside the body of Norman, works against that closure.

Cut to Marion’s car being pulled from the lake. This particular scene provides again a sort of closure to the story. But again, that closure is broken, with the parallel lines which traverse the screen, as I said above, in reference to the restoration of the order of the world.

In Psycho there is an imperfect closure, but it’s a closure after all. Hitchcock went further three years later, with The Birds (1963). As William Paul argues in Laughing Screaming. Modern Hollywood Horror and Comedy (Columbia University Press, 1984):

“The Birds took the move against closure even further by ending in the middle of a suspense sequence, absolutely refusing to resolve the immediate concerns of the narrative –will this small family group escape from the next possible bird attack- or the tensions among its characters.

A perfect example of attack on closure can be found in Carrie (dir. Brian De Palma, 1976). Paul says:

Carrie’s hand suddenly thrusting up through the charcoal, breaking Sue’s reverie to grab her by the arm, produced the requisite scream… Carrie‘s ending was the most direct assault yet on closure’s dominance in Hollywood films.

The absence of closure has become over the years in another constant in contemporary horror film. Leatherface with his chainsaw against the sunset, Michael Myers coming back to life over and over again, and Jason Voorhees emerging from Crystal Lake in the dream sequence at the end of Friday the 13th are just examples of this tendency that, again, had its origin in Psycho.

“Sound”

The soundtrack in Psycho is another landmark in the history of the horror genre. One cannot imagine the shower scene without the music it has. It seems hard to believe that Hitchcock didn’t want any music for the scene. Bernard Herrmann wrote it anyway and after having heard it, Hitchcock thought it was too good to discard it. But anecdotes aside, the music in Psycho, and in particular in the shower scene, is fundamental for the ulterior evolution of the horror genre.

The violin in that scene is so effective because it is used as percussion, suggesting knife strokes. If the volume is strong enough, one can feel the knife strokes as penetrating his body.

From Psycho on, horror movies started to pay attention to the sound effects. One excellent example of this is The Exorcist (dir. William Friedkin, 1973). The level of complexity achieved in this film, in reference to the sound, was already announced in Psycho

With the sound, I close this section in which I have tried to review the main innovations that Hitchcock introduced in Psycho, and which would prove fundamental in the posterior evolution of the horror genre. I’m sure that there are many more aspects which reaffirm the central position of Psycho as the pre-history of the contemporary horror genre, but the ones we have seen gives us a complete picture of the character of those innovations. To name just one of those other aspects one could bring here the pleasure of watching, the voyeuristic tendencies of Norman as a peeping Tom looking through the hole. This motif will be present at The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, for instance.

III. Influence of Psycho

It’s very difficult to trace the influence of Psycho precisely because of its pervasiveness. There is virtually no horror, thriller, or suspense film made after 1960 which has not been influenced by Psycho

It’s obvious the clear influence that Psycho had in horror directors such as George A. Romero, Tobe Hooper, John Carpenter, Wes Craven, and Sean S. Cunningham in the ’70s, to name just a few. More personal directors, such as David Lynch, have also found in Hitchcock a never-ending source of ideas and motives.

Hitchcock’s influence is not limited to the suspense-thriller-horror genres. Directors such as Steven Spielberg or Martin Scorsese have been deeply influenced by Hitchcock’s films. In Scorsese’s words (quoted from CNN digital edition, August 13, 1999):

“Vertigo is … important to me -‘essential’ would be more like it- because it has a hero driven purely by obsession. I’ve always been attracted in my own work to heroes motivated by obsession, and on that level, Vertigo strikes a deep chord in me every time I see it.”

Probably the most obvious influence of Psycho has been the creation of a sub-genre: the slasher film. Clover puts it this way:

“The appointed ancestor of the slasher film is Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Its elements are familiar: the killer is the psychotic product of a sick family, but still recognizably human; the victim is a beautiful, sexually active woman; the localization is not-home, at a Terrible Place; the weapon is something other than a gun; the attack is registered from the victim’s point of view and comes with shocking suddenness.

Another one of the many products in which the influence of Psycho can be appreciated is in the Italian giallo. The most relevant aspect here is the character of Norman Bates. His condition of human being profoundly disturbed but human, made possible the swift from the monsters of classical horror film to the disturbing psychopaths of today. Another clear influence on the giallo film is the British film Peeping Tom (dir. Michael Powell, 1960).

The examination of the giallo film takes us into another director clearly influenced by Hitchcock: Brian De Palma. Movies such as Sisters, Dressed to Kill, or Body Double are pure imitations of Hitchcock. De Palma only copies the superficial aspects and themes, even specific scenes of Hitchcock’s films. In that sense, De Palma may be considered a Hitchcock imitator. He’s imitating Hitchcock, copying him, but not following in his footsteps.

IV. Conclusion

James Naremore, in Filmguide to “Psycho” (Indiana University Press, 1973) talks about the importance of the film:

Psycho is especially important to us retrospectively, because we can see that it stands at an interesting juncture in the development of the American popular film. It is midway between the repressive manners of the classic Hollywood studio movie (Janet Leigh wears a bra) and the “liberated” ethos of the R-rated contemporary film (Janet Leigh is shown in bed with a man at midday). It might seem to point toward the “new” morality, but it belongs, as Durgnat has pointed out, squarely within the traditions of the “old” morality. It gives the audience satisfaction by titillating their libidos, but it makes them uneasy accomplices to a psychopath, cautious about their instincts. Clearly it does not induce us to live the sexually repressed life of a Norman Bates, but neither does it make us think that sex is good and innocent.

It’s that interstitiality that makes Psycho so interesting. It’s the last classical horror film, but at the same time it’s the first contemporary horror film. Actually it’s none of those things, and both at the same time. Psycho has one foot inside classical horror film and one foot outside of it.

Linda Williams, in “When Women Look: A Sequel” in Senses of Cinema, issue 15, July-August 2001, comments on the importance of Psycho:

“If any genre can be said to have continued the tradition of the cinema of attractions, it is certainly the horror-thriller. And if any single film can be said to have revived the acute, visceral shock of these attractions, it is certainly Psycho.”

There’s a big difference between the horror films made before and after Psycho. This particular film introduced so many new elements that prompted the apparition of a new way of understanding horror. One in which the destruction of the body is the central sign around which the narrative is constructed. To put it in other words, the defining moment becomes the opening of the body; and all this starts with the shower scene in Psycho.

Psycho is a descent into hell, from the bird’s eye view of the first scene, to the depths of the swamp in the closing image. We never get out of the swamp. As I have pointed out throughout this paper, Psycho is just a starting point, a sort of first step. The subsequent steps would present movies such as Night of the Living Dead, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Halloween, or Friday the 13th, to name just a few.

All the elements present in contemporary horror movie were already present, although some in a latent state, in Psycho. Not only the story/narrative, and the narrating were changed forever with this film; the experience of going to the theatre was also reborn. Psycho created the phenomenon of the long lines in movie theatres. Hitchcock defied the structures of classical Hollywood cinema by addressing his movie to a different audience. Psycho was the clear antecedent of the contemporary commercial films, addressed to an audience of teenagers. Most of the themes that Hitchcock introduced in Psycho had been used before in drive-in theatres, but never in the context of Hollywood mainstream cinema: this was the first time that they arrived to a large audience.

I would argue that the contemporary horror film still revolves around the triplet of films I have been discussing, that is, Psycho, The Night of the Living Dead, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Actually, there is only one film movie in the last 30 years which has dared to explore a different path, deep in the woods near Burkittsville, Maryland. Obviously, I’m referring to The Blair Witch Project (1999), directed by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, but that’s another story.

It’s for all these reasons that I decided to call this essay “Psycho: The Mother of All Horrors.”

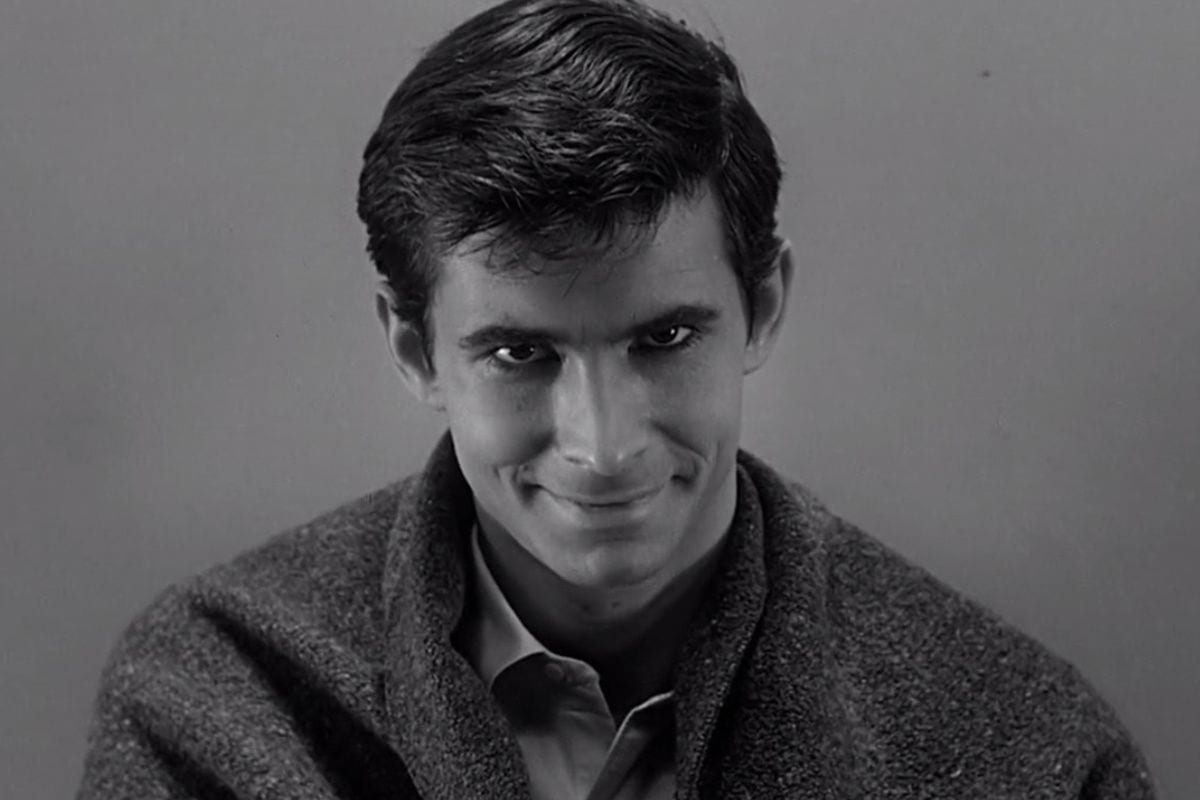

- Anthony Perkins in 'Psycho'

- "Get Out of the Shower": The 'Shower Scene' and Hitchcock's ...

- Hitchcock, 'Psycho', and '78/52: Hitchcock's Shower Scene ...

- 'Psycho' and the Scene that Changed Modern Horror Forever ...

- Death Is Neither Delusion Nor Denial in 'She Dies Tomorrow' - PopMatters

- 15 Classic Horror Films That Just Won't Die - PopMatters