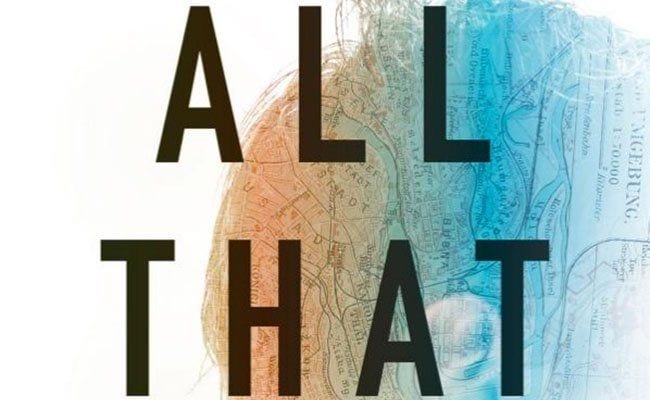

With All That Man Is, David Szalay sets out on a nearly impossible task. The audacity of the title would surely leave room for readers to criticize him for falling short of such an ambitious project. Yet, All That Man Is manages to accomplish exactly what Szalay promises.

Somewhere within what seems at first to be only nine short stories, it becomes clear that such an ambitious novel as this could only have been told in the way Szalay chose, as vignettes. Is it a novel? Somehow, yes. The stories need to be read in the order Szalay has them arranged. Something ineffable would be lost if they were read out of their order of appearance.

All That Man Is must necessarily be the story of multiple men rather than one man throughout his lifetime. Each story occurrs more or less in the same time period. Szalay knew what he was doing; a project as ambitious as trying to encapsulate all that modern man is in a single novel could not have been told in the ordinary linear fashion. Nevertheless, there is a linearity, not only in the incremental way each man ages, but inasmuch as what underlies them all is of greater importance than what obviously distinguishes each from the other.

Most rewardingly, Szalay doesn’t take the easy way out with any of his stories. Men are uncomfortable, perhaps offensive to some sensibilities but ultimately sympathetic. None are caricatures, and each story ends without some life-changing cataclysm (despite early signs that trend that way). Szalay’s novel is as much about men as about life’s unpredictability. The moments accrue one by one. Moments of careful planning, self-doubt, and the consequences of each; moments of saying things that cannot be taken back and moments of recognizing that events are beyond your control. Young men interrogate old men, try to do so understandingly, but only recognize their passage from one category to the other when it’s already behind them. The men in these chapters grow older, they gray, their sex lives persist but change, wane, and somewhere in the middle of it all, a life forms without ever having recognized the point it transitioned from burgeoning to burdened.

The moment between “There’s plenty of time left” and “How did I get here?” passes without any recognition by the characters because, of course, it isn’t a documentable moment. By the sixth chapter, the story seems to have wandered somewhere its central character hasn’t expected, not off track but simply drifted slightly out of the lane, carried by the inertia of young ambitions. Something elusive has begun to dawn on the man in his 40s, “This is all there is. It’s not a joke. Life is not a joke.” It happens as quietly and unexpectedly for the characters as it does for the reader.

Sex, purpose, and loneliness all play a role in the lives of the men at the center of the novel. Some take precedence in youth, some in old age, but there’s a moment where each one intersects with the novel’s central characters and draws the narrative along. In the end, in fact, the oldest man is shown to be the grandfather of the youngest. Vague ages — late 30s, 40s — leave room for both the characters and the reader to fudge the line. There’s always more time ahead than behind until there isn’t.

Time and loneliness creep up on the men. No one is ever ready for the inevitable, even though each character here (except perhaps the 17-year-old and the early 20-something) sees it coming. This sense that something is slipping from their grasp builds until in his 50s one man recognizes “[a] sense, essentially, that he had wasted his entire life, and now it was over.” It doesn’t necessarily matter whether some men are left with indications that their career is flourishing, or whether some are too young to have even fully embarked on a career. It’s impossible to imagine that each man wouldn’t eventually be confronted by this haunting uncertainty about his purpose.

All That Man Is is a novel that manages to pull a single linear narrative from nine seemingly disparate stories. These stories are driven by more than simply the ages of the characters. It’s difficult to distill exactly what that underlying element is, but it’s also undeniably clear that whatever is it that binds these nine men together it’s something essential to modern manhood.

In the last chapter, the 73-year-old contemplates his mortality and finds the idea of his life ending difficult to fathom. “The strangeness … is to do with the fact that the only world he knows is the one he perceives himself — and that world will die with him.” All That Man Is contains observations about life, mortality, and perception, but reading that passage near the end it’s also clear that something indefinable binds both the 70-year-old’s life and the lives of the other men who preceded him. Szalay has done a remarkable job of both documenting this and preserving its mystery.