5

Building the Slaves of Tomorrow

In late 1930, a year into the Great Depression, Dr. Phillips Thomas, an engineer for Westinghouse Electric Company, demonstrated to an audience at Chicago’s Armour Institute of Technology how machinery could aid humankind. As part of a campaign to sell Westinghouse products and recruit engineers, Thomas introduced new uses for a thirty-year-old technology, the vacuum tube. He carefully explained how vacuum tubes could extinguish fires, regulate room temperature, and build safer airplanes—all automatically. Such applications promised great improvements in safety and lifestyle, but in an era of engineering wizardry, they lacked the expected spectacle. Thomas, however, came prepared. Already an experienced showman, he had brought with him a device that could interest even the most skeptical observer: a black-skinned mechanical man he named Rastus.

While Thomas and Rastus appeared on stage, other mechanical men were rampaging across pulp magazines, films, stages, and storefronts. Sometimes these gigantic, lumbering, metallic men were called “robots,” but few symbolized workers. Continuing the transformations that had begun in the second half of the 1920s, Americans in the Great Depression increasingly used the term to refer to humanized machines that replaced workers rather than workers turned into machines by industrial labor. Yet, the uncannily human Rastus looked nothing like these robots. Where earlier engineers and costume designers had relied on wood, wallboard cutouts, or metal to give their robots a vaguely human facade, Thomas and S. M. Kintner, Westinghouse’s assistant vice president, molded rubber into a racist caricature that resembled the minstrel character after whom Rastus was named. His black body covered by overalls, a white shirt, and a pail hat, Rastus embodied stereotypes of docile black men; making the racial dimensions of Čapek’s robot explicit, he was, effectively, a “boy” slave for his engineer master.

During the performance, Rastus appeared on stage seated with an apple on his head while Thomas held a bow and arrow. In this reenactment of the story of Wilhelm Tell, however, the arrow employed a “photoelectric emitter” that shot a beam of light into a cell embedded in the robot’s eyes. Now activated, the photoelectric cell flipped a switch that lit a fuse just below the apple. As Rastus sat motionless, the apple magically fell to the floor—victim, it appeared, of a press of a button and a flash of light. The trick completed, Thomas pushed another button and Rastus bowed and mumbled a few words. The inventor then usually had the robot perform more routine tasks: sweeping the floors; switching lights on and off; sitting down and rising again. The message of this blackface performance could hardly have been clearer: the vacuum tube of yesterday had turned the rampaging robot of today into the slave of tomorrow.

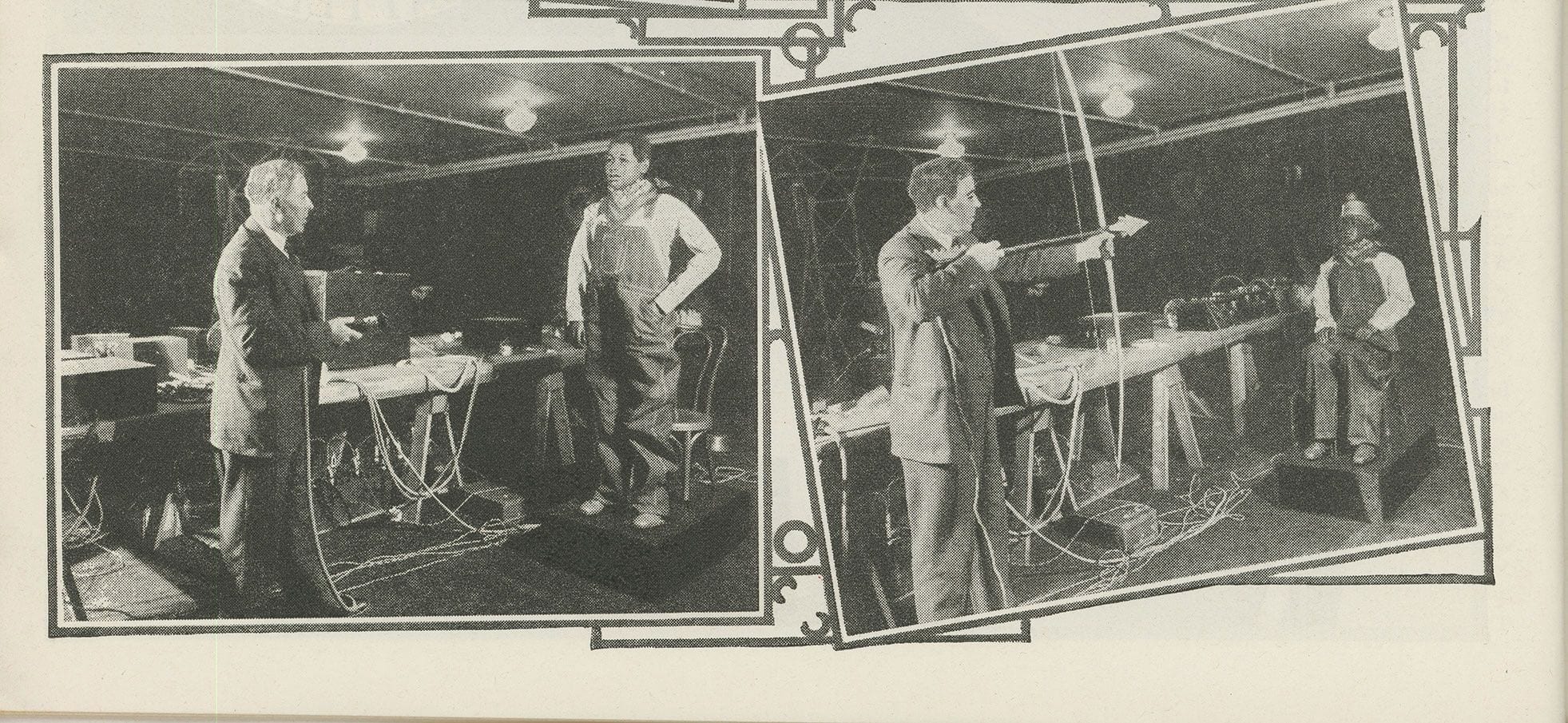

Fig. 5.1. Two photographs of “Rastus Robot” from Hugo Gernsback’s Radio-Craft magazine, in which S. M. Kinter uses his “photoelectric emitter” to reenact the legend of Wiliam Tell and to order Rastus to stand and sit.

The conservative Chicago Daily Tribune certainly understood the message. “‘Let Electrons Do It,’ Motto for Moderns” proclaimed a headline in the next day’s edition of the paper; “Dr. Phillips Thomas Tells of New Slaves.” “For a nickel,” the article stated, “you can buy 130,000 million million electrons and put them to work. An ounce of these slaves of the lamp of understanding represent 100,000 kilowatt hours of energy. You press a button and 160 million a second pass through the toaster wires on your breakfast table.” To clarify the importance of such power during the discontent of the Great Depression, the newspaper compared electrons to workers: electrons, “unlike all other creations, are all exactly alike and can be depended on for their actions.” More than a new tool, electrons were the submissive laborers that would transform the way American society produced its goods; they were, like Rastus, humanlike in their ability to serve but without the individuality that enabled people to resist domination.

Thomas and Rastus, performed their mechanical minstrel show for middle- and upper-class audiences across the United States and Canada in the early years of the Great Depression. After premiering at the National Electric Light Association convention in San Francisco in early 1930, the two performed in New York in November and then at the Armour Institute. From there, Thomas and Rastus traveled to Alberta for a meeting of the Canadian Electrical Association. Rastus reappeared in 1935 at the Syracuse Herald Progress Exposition for what seems to have been its final performance. The main archivist of Westinghouse’s robots claims that Rastus’s rubber skin caused it to overheat and melt, a horrifying end to the only black robot the company built. After Rastus, Westinghouse never made another mechanical man that so uncannily crossed the boundaries between human and machine. Instead it maintained a strict division by building gigantic metallic-colored men which only marginally shared a shape with their controllers.

Rastus was one of six mechanical men and women built by Westinghouse between 1927 and 1939 to spread the company’s message of robotic slavery to middle- and upper-class white families. During that time, Rastus and its “family”—Mr. Televox, Katrina van Televox, Telelux, Willie Vocalite, and Elektro—performed at management and professional clubs, fraternal lodges, department stores, technical colleges, and local and international fairs across the United States and Canada. Everywhere they appeared, the machines attracted large crowds and sensationalized newspaper coverage. Even people in small towns learned of the robots as local newspapers reprinted stories of performances, often with astonishing, attention-grabbing headlines and photographs. These articles likely familiarized most Americans with the devices and, more important, taught them that these machines, rather than Čapek’s creatures, were robots. Though Westinghouse mostly avoided the term robot, the press seized upon it to stimulate its readers’ imaginations even further. When it included two photographs of Rastus and Kintner on a spread celebrating amazing advancements in electrical equipment, for instance, Hugo Gernsback’s Radio-Craft magazine dubbed the device, “Mr. Rastus Robot, the most life-like of mechanical men,” before excitedly explaining its control mechanism. By the mid-1930s, practically any machine that seemed to duplicate human features or behaviors, regardless of its appearance, could be called a robot. More than any other device, Westinghouse’s robots popularized Čapek’s term, though that did not mean that audiences accepted the ideological message the company wished to convey.

Though Rastus was neither the first of its kind (Mr. Televox was) nor the most popular (that was Elektro), as the only black-faced robot Westinghouse produced, Rastus highlighted the company’s message better than any other. Deeply troubled by growing skepticism of the machine age, Westinghouse designed its devices to pacify the symbol of the rampaging robot. The company’s white and metallic robots achieved this through humanization: they had unique names, smoked cigarettes, and, once given artificial voice boxes, had the ability to tell jokes—even about sex. But Rastus, with its minstrel show name and docile appearance, was itself the joke. While its fellow robots hid their enslavement beneath a veneer of friendship and equality, Rastus was an eager to please, crude caricature; explicitly a slave, it was far from the celebration of blackness found in the era’s popular culture and places such as Chicago and Harlem. Since the nineteenth century, American advocates for industrialization had talked about machines as the new slaves that would enable the country to fulfill its democratic and moral promise. But the synthetic blackness of Rastus did power over machinery and the bodies of black men.

Dustin A. Abnet is assistant professor of American studies at California State University, Fullerton.

Excerpt reprinted with permission from The American Robot: A Cultural History, by Dustin A. Abnet, published by the University of Chicago Press (footnotes omitted). © 2020 by the University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.