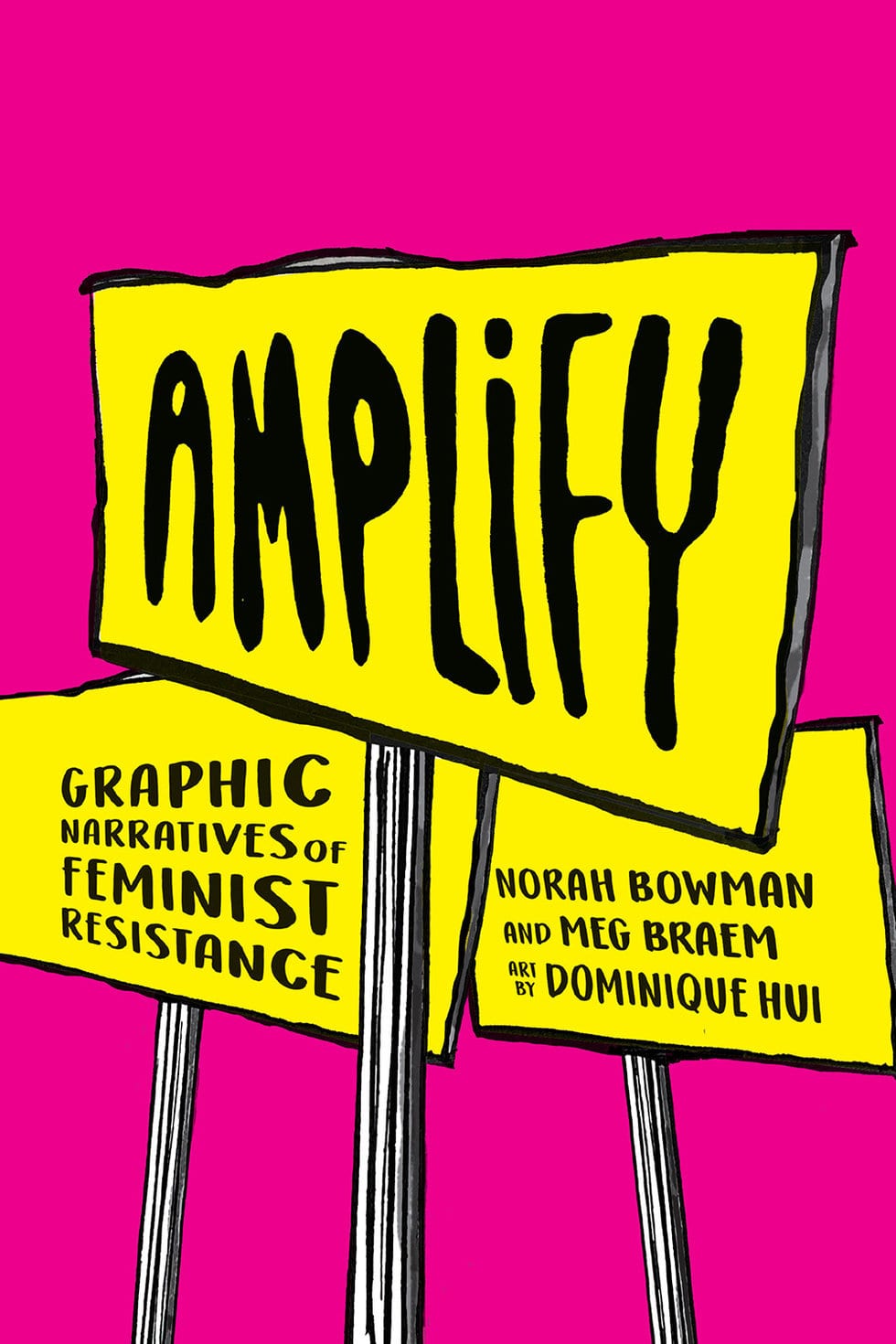

Amplify is not your typical textbook—and not just because 115 of its 166 pages are comics. Professor Norah Bowman selected seven feminists and feminist organizations, transformed their histories into stories with the aid of playwright Meg Braem, and then handed those scripted stories to comics artist Dominique Hui to transform into graphic narratives with the aim of motivating new acts of feminist resistance from inspired readers.

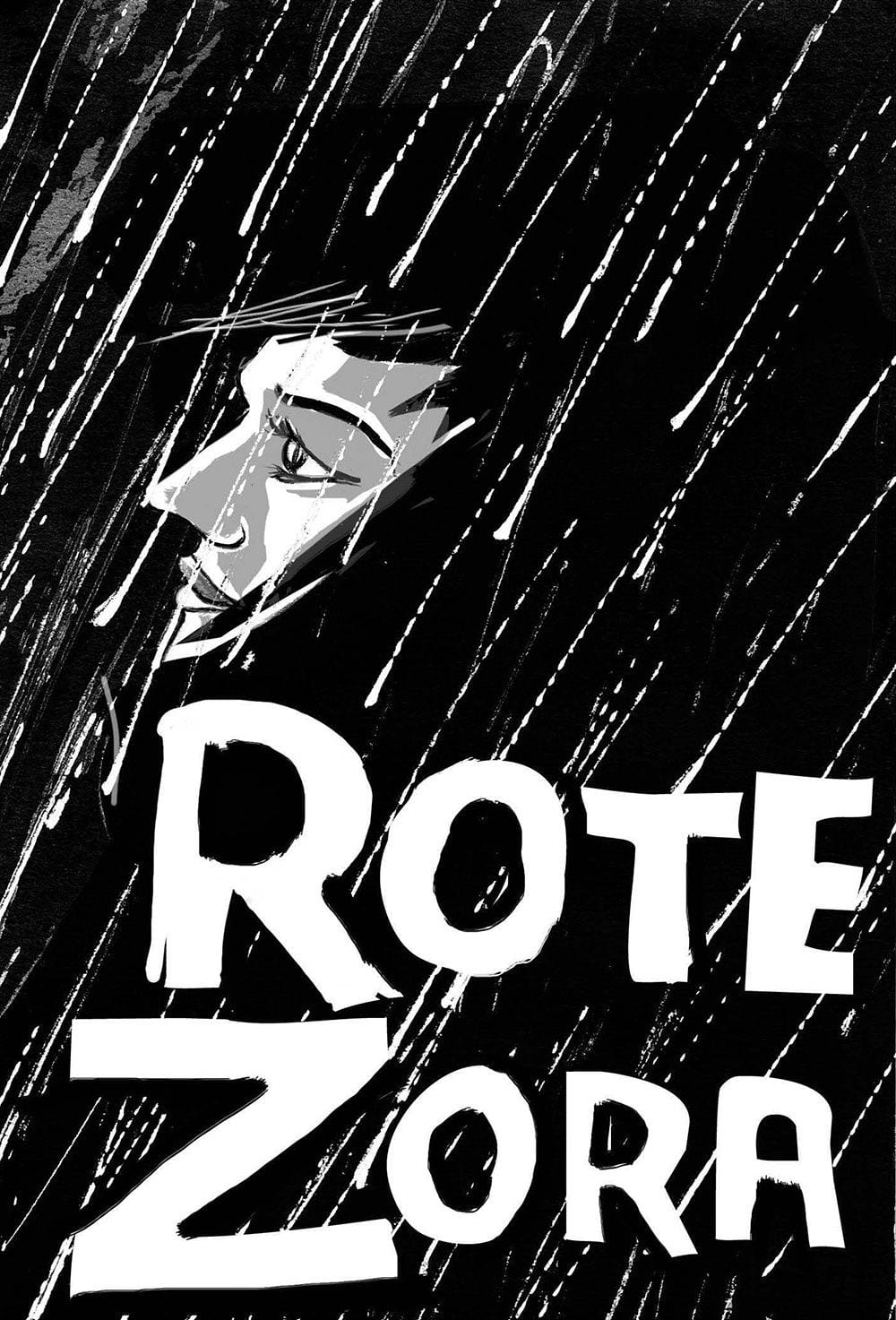

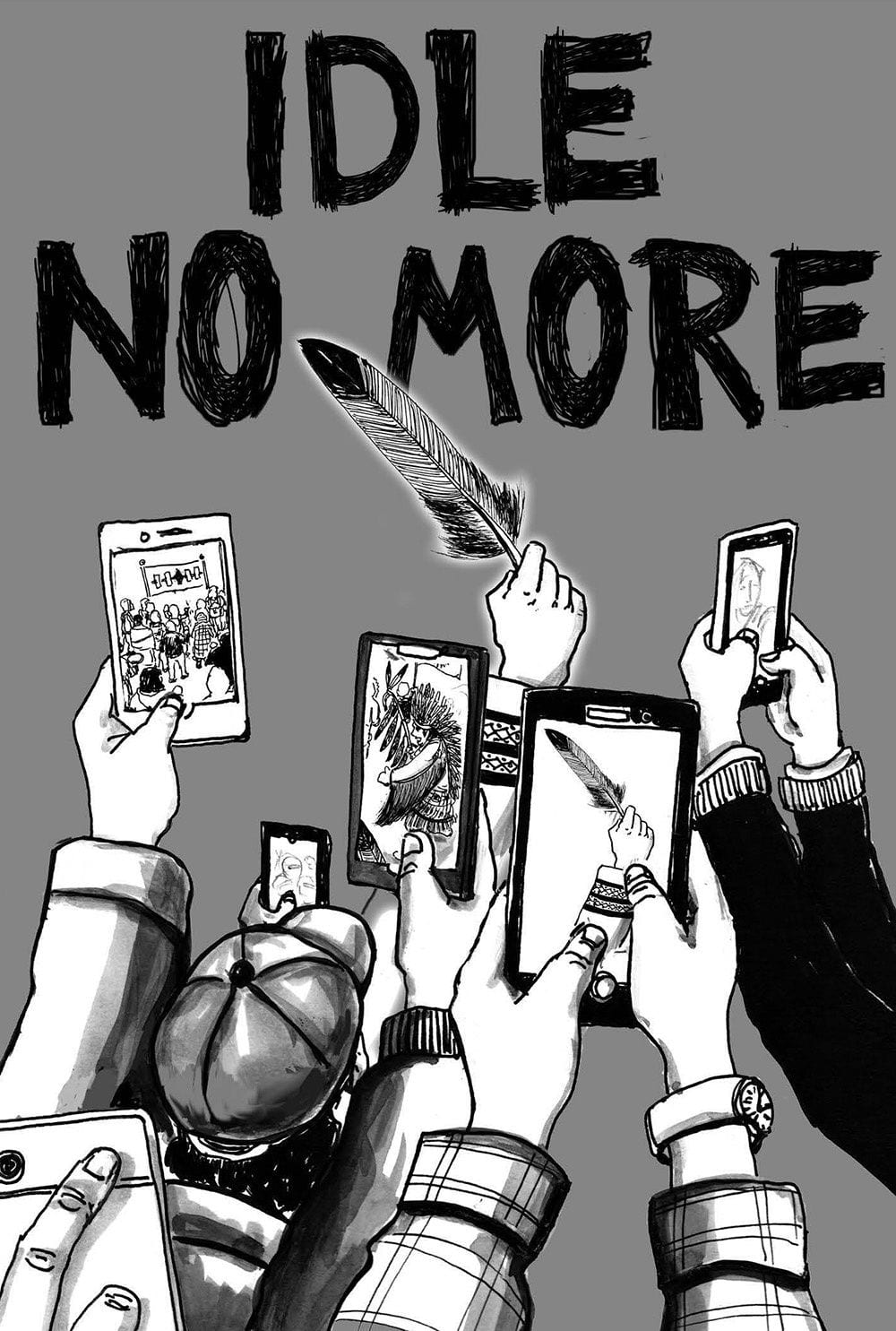

The focus is intersectional, so in addition to the white women of Pussy Riot and Rote Zora, the collection highlights mostly international women of color. Since the press is the University of Toronto’s, two of the seven narratives appropriately take place in Canada—with a Canadian cameo concluding a third. The US appears only once, as do India, Russia, Liberia, and Germany. The inclusion of a South American narrative would have completed the range of continents, and the omission of a Muslim feminist (Malala Yousafzai perhaps?) is equally disappointing. But the project offers only a sampling, not a canonical list of feminist icons. The field is rich. Instead of seven narratives, future editions of Amplify could include 14 or 21 and still not be definitive.

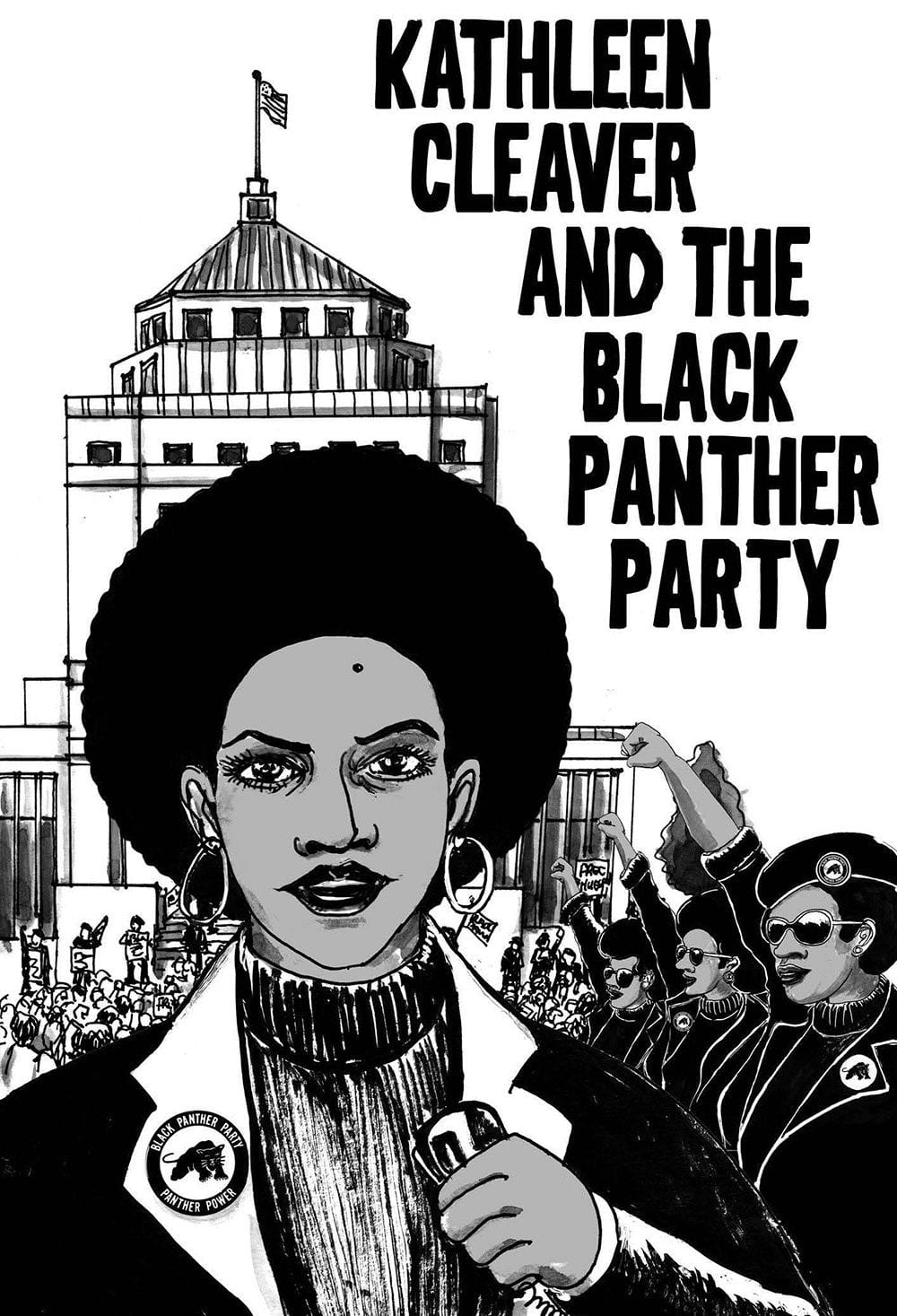

Since the focus is primarily and usefully on the 21st century, the two 1970s-era narratives seem oddly placed. They’re also atypically violent, featuring the firearms and bombs employed by protesters. Most of the vignettes instead highlight the power of modern media: TV, online petitions, YouTube, Twitter. This matches the collection’s pedagogical focus, since readers are far more likely to reach for their cellphones than for Kathleen Neal‘s rifle. And though Rote Zora’s 45 fire bombings have somehow resulted in no injuries, no textbook can or should provide the necessary basics of skill and luck that requires.

Bowman’s basics are more academic, including a 24-entry glossary of such terms as ‘lateral violence’ and ‘heteronormativity’. She discusses the more centrally defining term intersectional feminism in her introduction, urging readers’ local communities and grassroots organizations to combat multiple kinds of oppressions. The goals are lofty, though also classroom-focused, with reading lists and discussion questions capping each chapter. As much as I appreciate a well formatted Works Cited, is an inspired community action group going to interlibrary-loan an essay from the Journal of the American Academy of Religion, or spend time discussing questions better suited to reading quizzes (“For what crime were the women of Pussy Riot imprisoned, and how long was their sentence?”)?

I debated at times who Amplify is most addressing since the 11- to 22-page comics communicate their content with rudimentary directness. While the historical events might welcome critical engagement—when, for instance, is it okay to fire bomb a porn shop?—the graphic adaptations echo the narrative logic of children’s tales, condensing time into summarizing dialogue that replaces what it represents. When Kathleen Neal, for example, appears in the doorway of the Blank Panthers meeting room after the arrest of Huey Newtown, her speech balloons declare: “I’m Kathleen Neal, from Atlanta. I understand there’s a crisis in the organization.” A member shouts: “They arrested Huey!” A 100-word caption box spell out the facts on the previous page, making the response redundant. Bowman’s afterword (she includes one for each chapter) is redundant too, repeating much of the same information covered by the comic.

The afterword also produces contradictions. Though the graphic narrative implies that Neal traveled to California to join the Black Panthers in response to Newton’s arrest, Bowman later explains that Neal had already met her husband, Black Panther member Eldridge Cleaver, and took up Newton’s cause only after becoming a member herself. The difference is perhaps minor—and I appreciate the authors not portraying Neal as an appendage to her husband. Still, the contradiction is unnecessary and situates the comics as something other than exacting nonfiction.

The Leymah Gbowee comic treats time similarly, presenting a 2,000-woman protest on the outskirts of Monrovia, Liberia as Gbowee’s first organized event and combining it with a march outside the parliament building as if the two were consecutive actions by the same gathering of people. Bowman explains afterwards that Gbowee didn’t just send “out a message to the women of Liberia hoping they would come,” as her talk balloon states. She co-founded the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace, a religiously diverse organization that undertook multiple actions, culminating in the parliament march and peace talks that eventually resulted in the collapse of the Charles Taylor dictatorship.

Again, Bowman’s afterward expands on the comic, adding absent nuance. While this is helpful, the effect is odd since Bowman co-wrote the comics and so helped create the gaps she later fills. Why not just script the comics differently? According to the preface, Braem was “in charge of storytelling and drama”, and so the based-on-a-true-story condensing is presumably hers. The juxtaposition of the two narrative forms, the comics and their prose-only afterwards, are potentially intriguing, but the result here is neither a harmonizing whole nor a structured point-counterpoint but a surprising undercurrent of mistrust in comics to represent history independently of traditional scholarly apparatus. So I would augment Bowman’s reading lists with at least two more comics-specific texts: Joseph Witek’s Comic Books as History (University Press of Mississippi, 1989) and Hilary Chute’s Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics and Documentary Form (Harvard University Press, 2016).

The third author, Hui, used Bowman’s photo archives to illustrate the scripts, giving her pleasantly loose ink style a different kind of authenticity. While her black and white rendering remains largely consistent, her layouts vary with each chapter and often each page, reflecting the ever-changing topics. She also displays the occasional visual flourish—the diagonal lines of lyrics emanating through the full-page Pussy Riot concert panel is my favorite. I also admire her careful vacillation in reproduction sizings. When Gbowee’s portrait narrates in present-tense, the lines of her head and clothing are granularly thin with meticulous detail, but her flashback images are enlarged to create thicker, bolder lines that further contrast the two time periods.

Though I’m not sure if these comics ultimately amplify their subject matters or merely alter them through a different medium and documentary ethos, Amplify‘s goals are laudable and their results engaging.