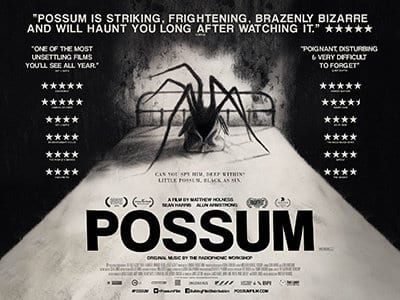

Possum (2018), the feature debut of Matthew Holness, tells the story of disgraced children’s puppeteer Philip (Sean Harris). Returning to his childhood home, he is forced to confront his sinister stepfather Maurice (Alun Armstrong), and the horrors of the past that have haunted him his whole life.

Holness is popularly known for his alter ego ‘Garth Marenghi’ from the cult TV series Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace (Channel 4, 2004), which Holness co-created, wrote and starred in. His short films include A Gun for George (2011), The Snipest (2012) for Sky’s Playhouse Presents series and Smutch (2016) for its Halloween Comedy Shorts series. Away from the screen, he has contributed short stories to the Comma Press anthologies: Protest Stories of Resistance (2012), Phobic: Modern Horror Stories (2007), and the short story Possum, which his feature film is based on to The New Uncanny (2018).

In conversation with PopMatters, Holness discusses his attraction to horror and the relationship between his literary and filmic storytelling. He also reflects upon creating a dream logic for Possum and the importance of affording the audience freedom to connect with their own fears.

Why storytelling as a means of expression? Was there an inspirational or defining moment?

I have always wanted to write stuff and I was always most interested in creative writing at school, where I wrote lots of stories. They were always the most fun thing I did, and so yeah, I have always wanted to do it. I have never entertained the thought of doing anything else, and so I guess it has just always been there.

Then to varying degrees in terms of what kind of stuff I write, that has changed a bit. For a while I wanted to just do comedy and specialise in that, and now I just find that I would rather make horror films and write horror stories, that kind of thing.

What drew you to horror?

I don’t know really, I have always been drawn to it. I guess I watched a lot of Hammer films when I was a kid, so I was obsessed with Dracula and Frankenstein and all of that stuff. I lived in Whitstable, where Peter Cushing lived. We’d occasionally see him down the street and I got his autograph outside a bookshop once. I think I had that sense of Van Helsing living in the same town, and it just felt like a natural part of my childhood.

It didn’t feel like it was odd to watch horror films, even though I can remember when my mom asked: “Can I let my two boys say hello to you? They are huge fans.” He was actually quite concerned at what films we’d been watching [laughs], but yeah, that and westerns were always the thing I was most interested in.

Horror was always something that was less frowned upon in those days. You had things like public information films that were played out between children’s programming, and so that frightening adult world was always there. You always had that sense of the impending nuclear war as well, so there was certainly always something that was feeding the anxieties of childhood.

Does the experience of making a film change your appreciation for those filmmakers and films you have a particular admiration for?

Yeah, it absolutely does and you realise how brilliant certain directors are. For example, just before I went into shooting Possum, I watched John Carpenter’s TV movie he made just before Halloween (1978). I think it was called Someone’s Watching Me, and he was obviously working with an established TV crew, and it was very much a product of the TV system. So it’s quite crude and there’s a lot in it that you feel he was having to do certain things to fit in with the look of a TV programme.

…[I]t’s very good, it’s not something that I think is bad, but there’s such a leap up between that and Halloween, which I think he went straight into making. Suddenly you look at that and it’s just so much more impressive and he’s in full control of what he’s doing as a director.

When you watch something like that you really appreciate the artistry and the talent that directors like him have, and that he was able to just use at that point. He went to film school, and I guess he’d done a lot of filmmaking with the early amateurish films that everyone will make if you are going into the business, because obviously you have to learn what to do.

But being in the same position of making your first film, it’s inspiring at the same time as being awe-inspiring [laughs]. It’s intimidating in many ways, but it makes you respect [other films] a lot more. But then you also learn that way, and you find out how they’ve done things, and end up realising why they filmed certain things a certain way. They are just good educational realisations as well, and you learn the more you do.

I’m interested in the way forms or the stages of a process bleed into and inform one another. How do perceive the influence of your literary short stories on your approach towards filmic storytelling, and vice versa?

Well, it’s interesting because I always find the short form literary narrative structure that best suits the feature film is the novella story – it’s generally the kind of stories that last for, I don’t know, 50,000 words or less. They always seem to make very good feature films and it’s often the feature films that try to cram a full novel in that don’t work so well. It’s interesting, because a lot of novelists get annoyed at the adaptation of their work and they will dismiss them saying: “It’s not the book.” It can’t be the book, that’s the thing. You can’t turn a huge novel into a decent ninety minute film; you have to streamline that narrative to fit the form.

I found the more I film scripts I write, the better prose writing becomes because you learn to cut to the chase with your dialogue. You realise that the dialogue has to be functional, it has to move the plot along and it always has to be in conflict. Before I’d worked in scripting for film and TV I think there was a tendency to just write lots of dialogue that didn’t really go anywhere — feeling the characters. You can do that, novels can have that happen, but I feel films have to move on.

There’s an argument that Possum is quite a slow film, but that’s intentionally so because it’s about the character, it’s about the fact that he can’t move on, and he’s doing the same thing over and over again. But I think there are certain things that make films work, and that is pacing, and pacing is all about structure and moving the narrative forward at all times. That’s in your kind of a classic Hollywood narrative, so yeah, there are definitely different disciplines for writing prose and for writing scripts.

Again, short stories are different because they can be very short, they can be just about one scene, one place, one sole thing happening. Certainly with Possum I knew I needed to extend the narrative a bit, to widen it in order for it to be a film in which nothing much on the face of it happens. It needed a bigger sense of climax and confrontation than the original story had, even though the essentials of the short story are in the film.

As I get older I find that I’m appreciating films that feel simple on the surface, with their complexity coming through the emotions of the characters.

Yeah absolutely. I think you go through a phase where you grow up on exciting films. I grew up on westerns and sci-fi films, all of those things, and I always liked them. But you do get to a point where you want films to be more about the human experience, which obviously changes hugely as you get older. And you want films that tell stories about human beings, human relationships and failure.

I’m far less interested in happy films that just fit a format. There’s always a place for those films, but it all depends what mood you’re in, and I’m drawn more and more to films that are complex in terms that they are not necessarily going to give you the happy ending that you think you want. I like films that reflect reality a bit more. There’s obviously room for all, there’s room for escapism and there always should be in those films, but there are films that have their place that go against the grain, and don’t fit that standard narrative structure.

In my opinion, Possum allows for a reflection on the idea that films exist on a dream logic and are psychological constructs. Would you agree?

With something like Possum, what we are seeing is the world as Philip sees it. So it would cease to be the film that it is if you followed the logical world and path of events. There was some discussion in the development of the film as to, will we need to give the audience more to orientate themselves? Did we need to let the audience know what the police are doing; what’s happening with the missing boy? And those things all fit a crime narrative, something that’s essentially safe and secure for an audience. These are elements they recognise and are familiar with, that allows them to escape into a safe cinematic reality.

But with this it was important for me to not give the audience those safety nets, to not allow them to feel like they knew where they were. It was important that we didn’t tell them too much about what Philip had done, what his breakdown and shame was, and what he was coming home for. It was crucial because the more you knew, the more you felt you had a handle on it, and I think it’s important that we don’t know who he is and what he has done. We don’t know to what extent he is bad or good, and it allows the audience to bring themselves into it a bit more.

If you are tapping into fears and the psychology of the audience, you’ve got to allow the freedom to bring whatever they are frightened of to what they are watching. If you tell them what they are frightened of, then that’s far less powerful than actually suggesting that they look within, that they actually explore their subconscious in a way. In the end all you can create are symbols of what those fears mean to you, and hope that they translate to others.

There’s an obvious primal fear of spiders in the film, but it’s not about spiders. It’s just that it’s something about being trapped and being watched, about unpredictable movements and behaviour. There’s the whole idea of possum in the title, the idea of a state where you are resembling death, but when is it going to wake up? Is it dead; is it not? Will it wake up? If it wakes up will it be fast? It’s almost like the more you hide, or not hide, but the more you suggest rather than dictate those horrors and fears, the more it plays on psychology and those primal fears.

Often, we don’t know what’s haunting us. It can surprise us, and often what it is that frightens someone, they will not realise until after the event because it comes out of nowhere. Phobias are reactions to other fears that perhaps the individual is not aware of. So it was important with this to create that feel of a dream logic, that things are symbols to things and are not necessarily what it’s about. The puppet comes back and is it alive, is it dead? It kind of doesn’t matter – Philip thinks it is and that’s the important thing because we are seeing it through his eyes. What we are seeing is what he’s feeling, and we are trying to find our way to get to the route of what is driving him.

This is essentially the playfulness of the film, in which you approach the audience as an active collaborator.

Yes, I think so. It’s interesting that there are people who watch this film and they can’t get past revisiting the same territory. Philip goes out for walks and he goes back to the same places, and for some people that’s an issue: Why would you go back there, that’s repetitive? But actually there are people who watch it and think: Of course he goes back there, this is how his mind is working. It’s a bit of a test as to whether the film is tapping into what you are frightened of, that is if you go with Philip on that.

Most ghost stories take a long time and are slow paced. They build gradually and that is reflective of how fears creep up on us. Often you are suddenly frightened, but it has been growing for a while. You are not sure what it is, but your mind has been dwelling and ruminating on certain things that become something different to what the actual problem is. The fear is then blown up into something strange and odder than what it’s actually about. For people who find it a disturbing film, it is hopefully because they feel for Philip, and they feel that they recognise in his behaviour and in his mental patterns, something of the way perhaps their own minds work.

Filmmaker Christoph Behl remarked to me: “You are evolving, and after the film, you are not the same person as you were before.” Do you perceive there to be a transformative aspect to the creative process, and should the experience of watching a film offer the audience a transformative experience?

Well personally speaking, yes, I think it is a transformative process, but mainly because you are always learning. Technically I feel more equipped to make a feature film now than I did going into one for the first time. You learn to trust your own instincts more and to problem solve, and all of those things certainly strengthen you as a director, so that’s purely on a technical level.

On a personal psychological level, maybe you get more confidence from it. Maybe that in built confidence from knowing that you can create a reality that isn’t real, but is real for whoever is watching it, is something that yeah, you want to keep doing and you feel you can do better next time around. So I guess there is that, there is a real sense of achievement in creating a world that is essentially constructed and artificial that people believe in. I think from an audience point of view, I would hope people are transformed by films, and the ideal is you get a film that does move people to a point, or angers them to a point that they want to go out and reflect on the reality around them. It would be great if films did that and at the same time there’s always space for films that take you away from the reality. So I think you and an audience can change from a film, but it’s odd because films are essentially a form of entertainment, but they don’t have to be. There’s always a slight clash of expectation – what is this? And if you can surprise an audience by them thinking it’s going to be one thing, and it turns out to be something else entirely, then I think that’s great.

Possum is released in UK theatres by Bulldog Film Distribution today, 26 October 2018.