Fantagraphics has a thing for technological dystopias (Inés Estrada’s Alienation, O. Schrauwen’s Parallel Lives, Daniels and Passmore’s BTTM FDRS), or maybe that’s just what happens when you’re a publisher in the second decade of the 21st century. Their latest virtual nightmare spawned in Spain through the accomplished hands of comics artist Ana Galvañ. Her work is a welcome expansion of the familiar but still-rich genre of hi-tech futures on the fritz.

Though marketed to fans of Netflix’s Black Mirror, Galvañ’s Press Enter to Continue flows from an older tradition, with Twilight Zone and Outer Limits as more significant forebears. But even that resemblance is misleading. Galvañ’s tales would not make good TV. I mean that as a compliment—and with no implied insult to TV (I’m a Black Mirror fan too). Galvañ’s images are not simply storyboards presenting a visual narrative a snapshot at a time. They’re much weirder than that.

Most comics images seem straightforward: each depicts a moment in a sequenced event unfolding panel by panel in a world essentially like ours (or ours if ours had things like dragons or super-powered crime-fighters). That’s so obvious it seems silly to mention. Yet Galvañ’s images, while still performing that storyboard function, also challenge it at times and nearly overturn it at others.

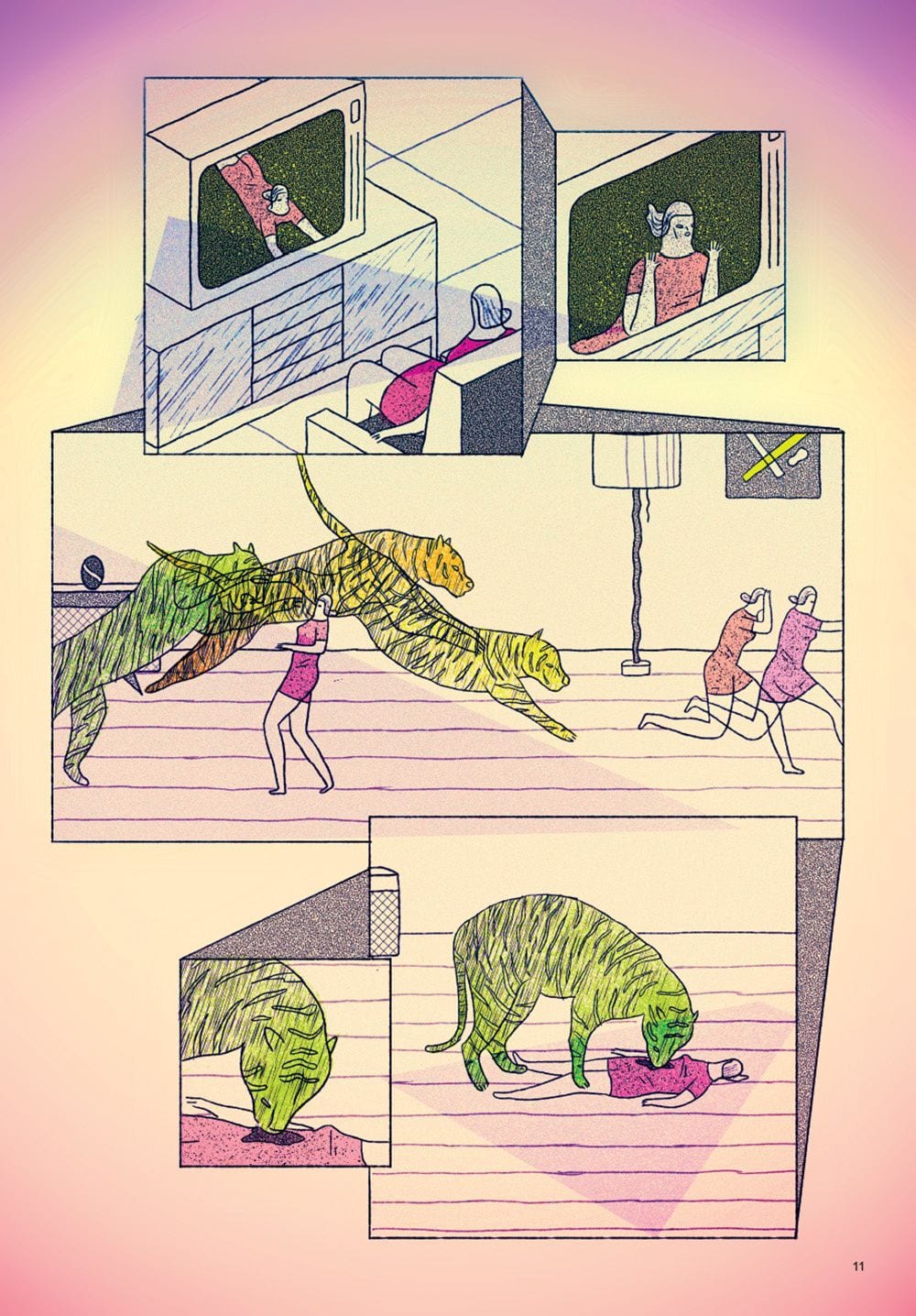

Take the first page of her first story: a woman walks across a room in four panels. Or I assume she’s a woman, because the ponytail and short dress are standard cartoon gender markers (though here happily non-sexualized). But where’s her mouth and chin? While not outside cartoon norms (missing noses and even necks are also a standard for female cartoon figures), the effect is ambiguous: is this person actually devoid of these body parts, or is that just how she’s drawn and we’re to understand that she actually does have a mouth and chin? And when her figure doubles in the second panel and then nearly divides in two in the next, are those movement-suggesting blurgits (like motion lines trailing behind Superman in flight) or is the character in the storyworld actually becoming two bodies—and then three?

(courtesy of Fantagraphics)

Usually a comics viewer doesn’t have to contemplate the relationship between the apparent image content and the metaphysical facts of its world. Usually images are secondary to words, with narration and/or dialogue doing the majority of the world-building work. But Galvañ ‘s eight-page story is wordless—and even title-less. The collection’s table of contents consists of five panels (four diamonds and one circle) with images excerpted from her five tales and a superimposed page number in each. Not a word anywhere. The other four stories do include words (three with dialogue, one with first-person narration), but that first story establishes a visual approach that pervades them all: what you see is not necessarily what you get.

That theme is central to the collection’s technological focus, where reality is never simply reality, but a constructed experience dependent on computers and other sci-fi gadgetry that scrambles identity into ambiguous parts. What does it mean when the female figure turns off the TV at the end? Were all of the images as imaginary as the ones on her screen or did one of her subdivided selves actually get eaten by a subdividing tiger? That we don’t know is part of the dystopic horror.

The other stories are equally strong, though I admire the wordless most. While Galvañ’s translator, Jamie Richards, provides effortless English, I again prefer the wordless sections of the second tale about a new member of a circus falling for the mysteriously masked Human Doll. Though I doubt whether her cartoon face actually is a mask (again, are the images like photographs of a weird world or weird interpretations of an unknowable world?), her secret is even stranger. I’m generally not a fan of sex scenes, but Galvañ’s sequence of geometric abstractions stray so far from erotica, human bodies are barely involved—and I’m not even sure the Human Doll is human. Again, the disturbing fun is in the not quite knowing.

(courtesy of Fantagraphics)

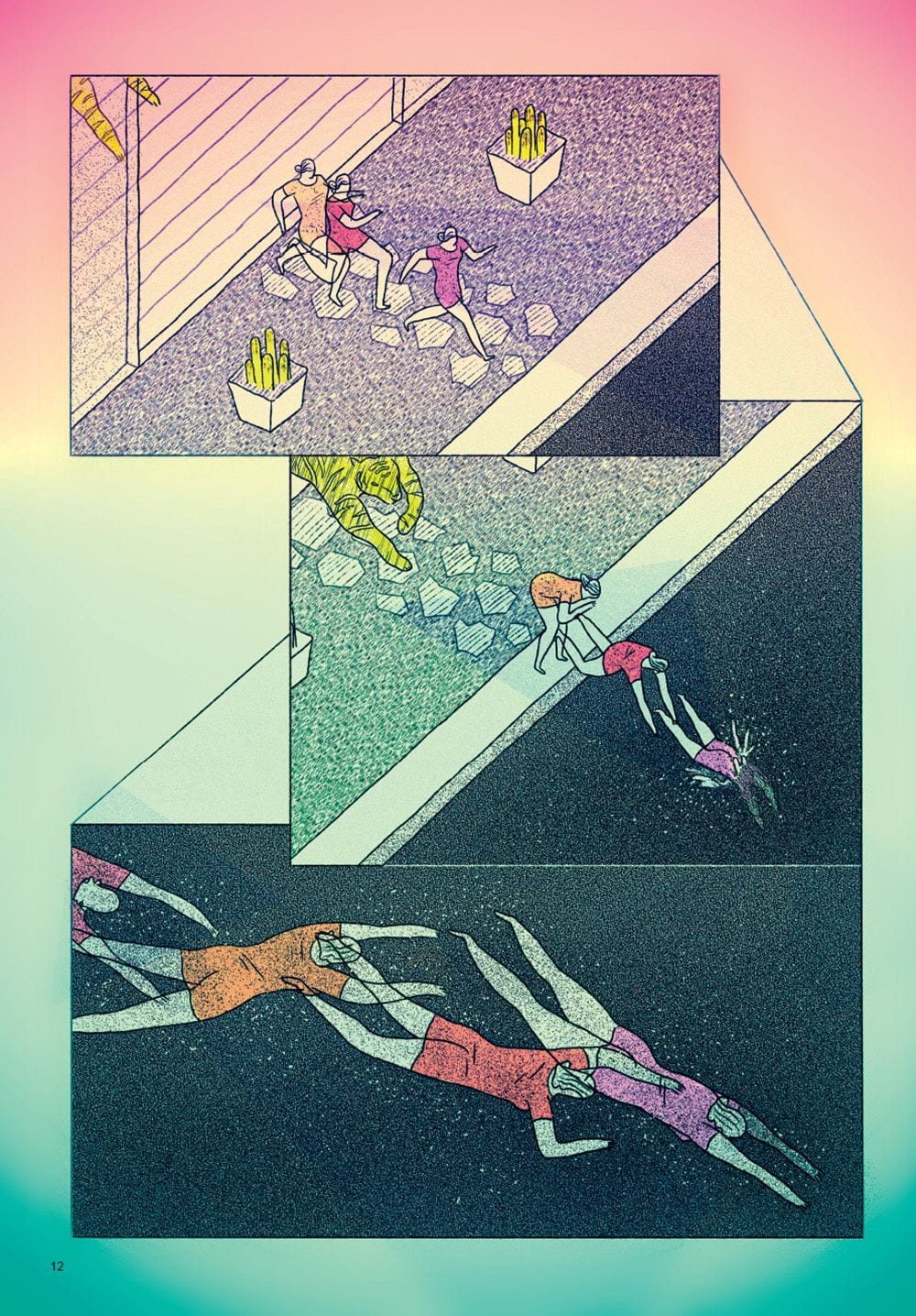

The third tale features a Kafka-esque job interview. While I accept that in the world of the story it’s perfectly normal for people to enter and exit buildings by crawling through oversized pet doors, the weird thing is a carryover from the first two stories: what do those geometric shapes of color mean? Rather than dividing colors according to the ink shapes of her characters and their environments, Galvañ incorporates free-floating circles and triangles that seem to be independent of the story worlds. While some suggest lines of vision or directions of movement or areas of visual interest, others seem merely decorative—yet in a way that intentionally undermines a sense of story coherence. Are the walls changing colors or, again, do they just look like they are? As odd as that may sound, it’s an old norm of superhero comics, where panels backgrounds shift at the whim of bored colorists. Galvañ just makes that oddness feel oddly tangible.

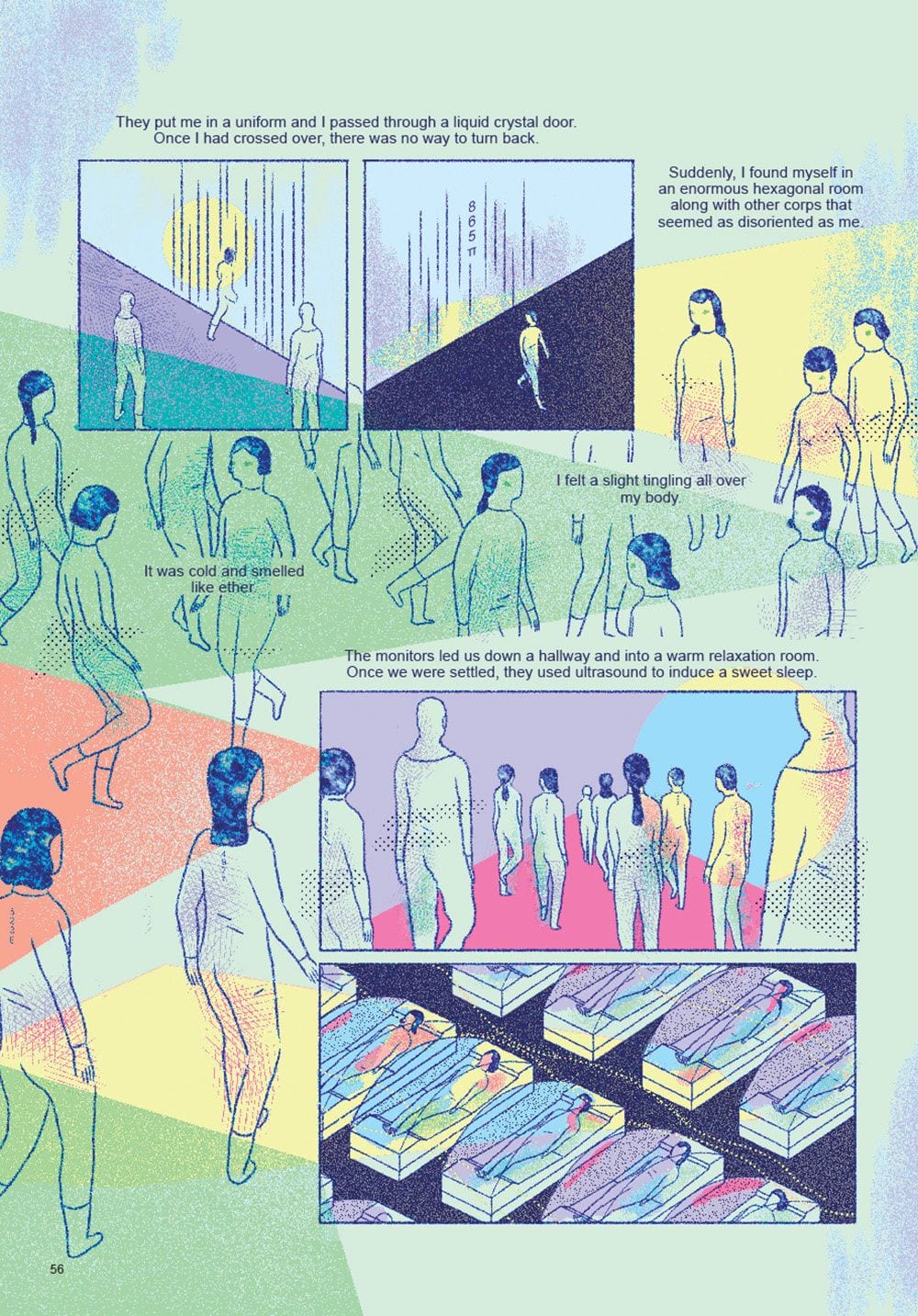

The fourth tale (seriously, they’re not titled) is the most traditionally futuristic with playfully named “gliders” and “liquid crystal doors” and “marvapends” and “sinusoidal analysis machines”. What these objects are supposed to be is as ambiguous as ever, but by giving them names (I can only imagine the translation challenges Richards faced) they become improbably familiar, almost clichés, the usual sci-fi stuff. While I enjoyed the effect less than the wordless ones, I appreciate the juxtaposition, an illustration of how powerfully words influence our understanding of stories, even comics stories that are supposedly more visual than linguistic.

Galvañ ends the collection on a strong note, with another bewildered protagonist haunted by the ambiguities of what to her should be familiar technology. Is the ghost-child forming pixel-by-pixel on her screens a repressed memory, a government-induced hallucination, or something weirder still? Galvañ, as usual, leaves it to us to decide. Or to not decide.

(courtesy of Fantagraphics)