There’s a certain clarity of human purpose in space exploration which is markedly lacking in almost all other fields of human endeavour.

At a time when millions of us simultaneously feel trapped within our social media bubbles, yet willingly conspire with each other to make it so, we can’t help but feel stunted, as individuals and species alike. From the identity struggles which cause us to gaze ever more narrowly inward, to the naked tribalism of nationalist and patriotic urges that cause us to rationalize war and genocide against our fellow human beings, it’s not surprising so many of us feel that humankind—and ourselves as individuals—are falling far short of our potential.

Yet in space exploration lies a sort of Utopian aspiration that assumes scientifically verifiable material form. Outer space reminds us of the naked beauty of our world before we visited such ruin upon it; it stirs our souls and our imagination in the way the first humans must have been awed by the natural world all about them: a world that appeared mysterious and bewildering and awesome, yet which they set themselves to understand, one small step at a time.

Outer space offers redemption, and hope, and reinvention all at once. Redemption: a chance to do over, and better, that which we have done so poorly on our own planet. Hope: a chance for a different and better future than the one which seems so likely if we remain stuck on this tiny overpopulated world. Reinvention: the chance that given a larger cosmic canvas than the one on which we are stuck today, we might give greater reign to a nobler iteration of humanity; that our species has the capacity to be more than the sum of our cell phones and our genocides.

A reminder of the cosmic scale of existence forces us to put ourselves in context regardless of how deeply we invest our cultural inventions with meaning. It forces us to put our own petty struggles in context and come to terms with the fundamental truth that we’re nothing more than a single species, regardless of what bizarre internal divisions and hierarchies we invent to divide ourselves from time to time.

Outer space is about the awe incurred at the universe’s natural wonder, but it is also the juncture at which wonder and comprehension, awe and understanding intersect. Our knowledge of the universe is still at an early stage, yet we know enough to know that we have the capacity to understand so much more. Mysteries are out there—but with struggle, and perseverance, and dedication, they can be grasped and understood.

Exploring space is about applying the entirety of what makes us human—our courage, our intellect, our desire to understand the world around us. And while the quest for space exploration could very easily descend into petty nationalist rivalry, the lesson of space exploration in the 20th century is that we achieve more when we work together than when we work apart.

Yes, America and the Soviet Union may have had their famous “space race”. But really, the history of space exploration is more about cooperation than competition. It was when Americans mustered the united economic, industrial and scientific strength of their country and its allies and dedicated it toward a collective effort to get into space, that we reached the moon. If we haven’t achieved equal levels of greatness since then, it’s because the competition of private industry fails to achieve the same levels of greatness that a collective national effort did.

Indeed, when the world cooperates, we achieve even more. From transnational research initiatives to the collective efforts that built and staffed the International Space Station, to the planetary monitoring systems which made the moon landing accessible to a global audience, there’s a clear over-arching message: we achieve more when we cooperate. One of the debates surrounding Damien Chazelle‘s 2018 film about the moon landing, First Man, surrounds the sidelining of the astronauts’ planting of an American flag on the moon. Yet the point conveyed by this artistic device—that the moon landing was a triumph not just for America, but for all of humanity—is one well worth making.

There are, of course, those pessimists who frown on space exploration. There are those who say it costs too much; that we should spend the money and resources on our own existence on this planet; that our destruction of environment and fellow humans alike suggest we shouldn’t even be permitted to risk contaminating the universe with our propensity toward exploitative destruction. There are some points in these arguments worth heeding, but as arguments against space exploration they require refuting.

Space exploration is costly, but there are few greater causes for us to deploy the resources society produces. The off-shoots of space science have been immense—the technological breakthroughs produced by space research, from medicine to manufacturing, more than make up for its expense in purely fiscal terms. Moreover, given the inability of most human societies to move past military expenditures, it offers the least destructive direction for military spending and military technology. During the height of America’s space program, vast amounts of its military budget were focused on building rockets that would take human scientists out to explore space, rather than building rockets to aim at each other and reduce each other’s cities to rubble. Which rockets served the higher cause?

Humanity has always struggled between its higher and lower impulses, and that’s not likely to ever go away. Robert Heinlein, the acclaimed science fiction author of the mid-20th century, tackled this very issue in his book, Have Space Suit—Will Travel (1958). In it, the protagonist Kip finds himself plucked up and put on trial by a sort of intergalactic security council, which is debating whether to destroy the Earth due to the menace it could pose to the galaxy now that humans, with all their propensity toward violence and destruction, are venturing beyond their planet. Spoiler alert—humanity is not entirely exonerated, but is given a reprieve. The security council is successfully persuaded that despite humanity’s failings, they are akin to the failings of children, still struggling to mature.

“[T]his race is young,” admits one of the other planetary representatives during the debate. “The infants of my own noble race bite and scratch each other—some even die from it. Even I behaved so, at one time… Yet does anyone here deny that I am civilized? …These are brutal savages and I don’t see how anyone could ever like them—but I say: give them their chance!”

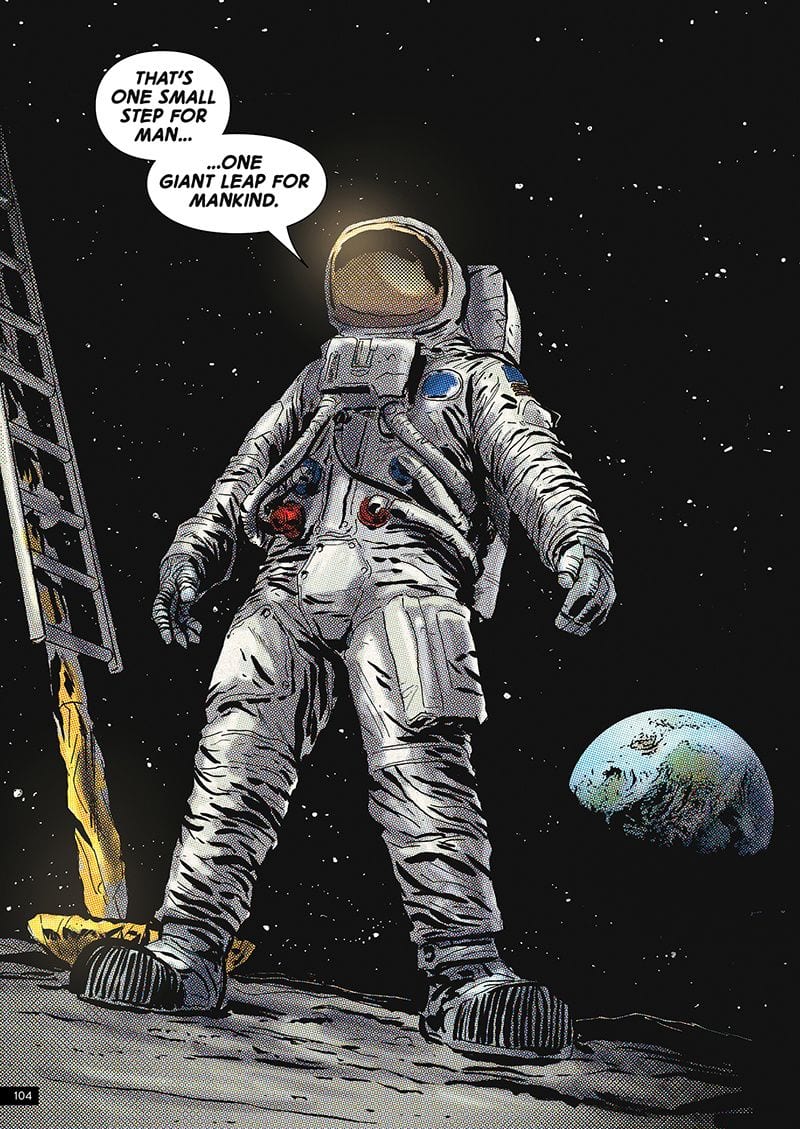

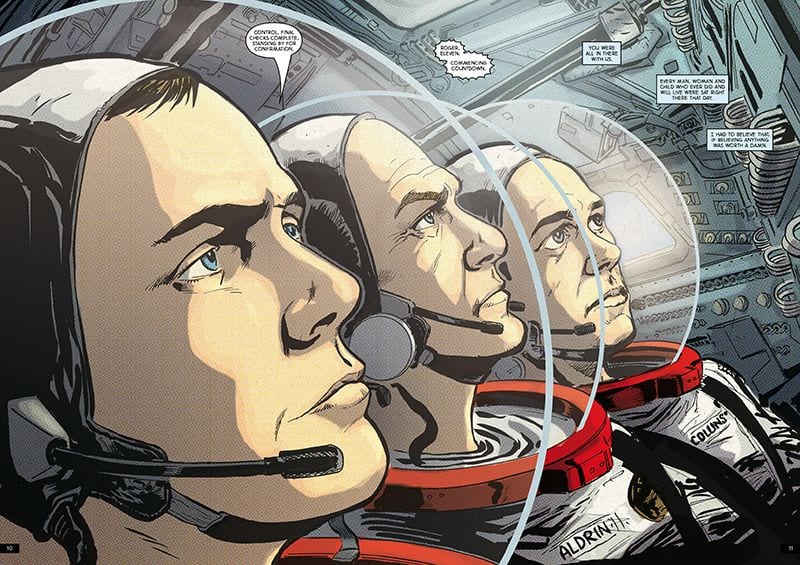

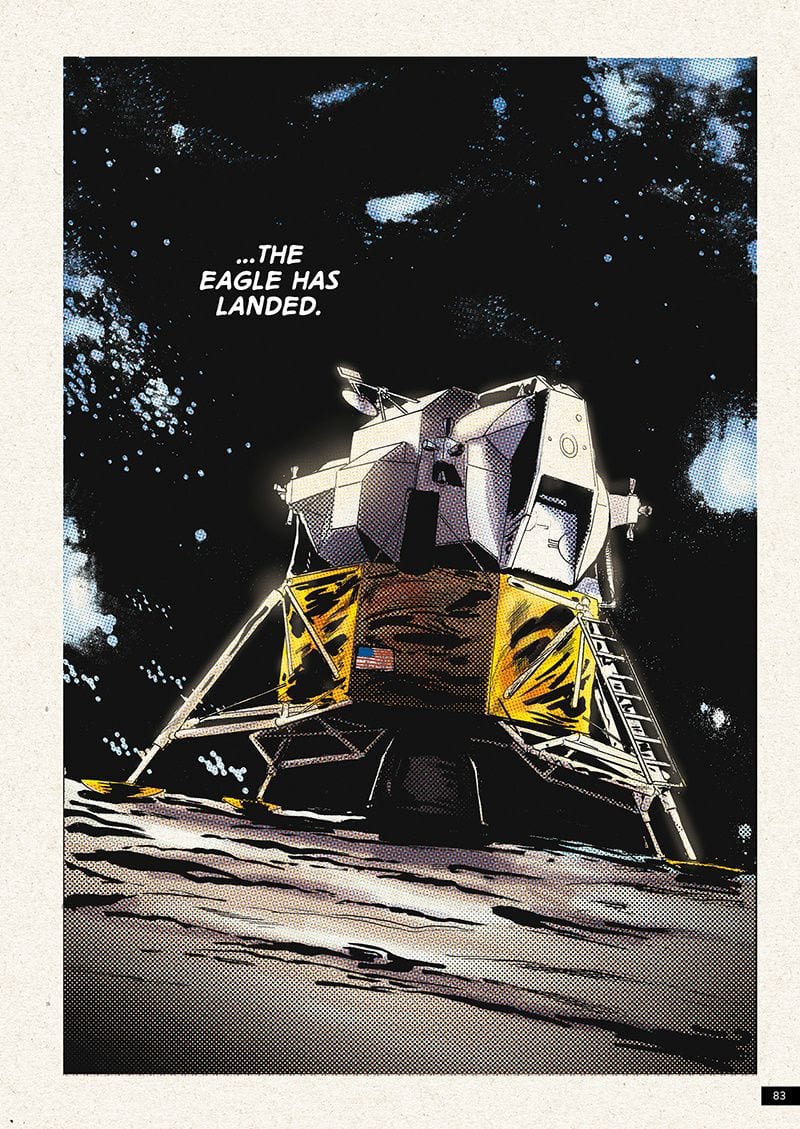

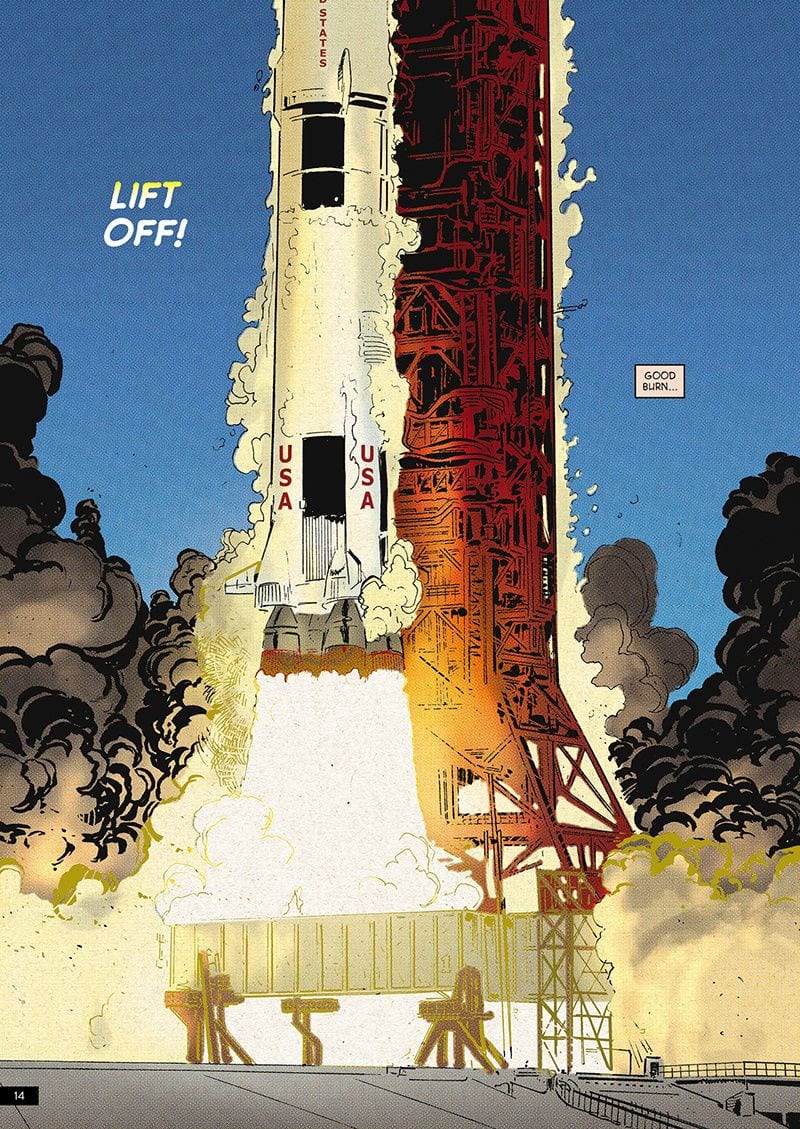

Apollo, a new graphic novel based on the moon landing, lends itself well to this optimistic portrayal of humanity’s potential. The book depicts, in gorgeously illustrated comic form, the moon landing. It’s mostly a straight-forward portrayal. There’s still potential for a longer book to do a more detailed telling: this graphic novel concentrates on the key moments. Those moments are presented in full technical detail (footnotes explaining the jargon and acronyms), yet the long spaces in between are glossed over. The effect is more artistic than historical, although the book endeavors to do both. There’s a focus, via flashbacks, on the astronauts’ humanity—on Buzz Aldrin‘s contentious relationship with his father and on his bitterness at being the second man to set foot on the moon, on Neil Armstrong‘s complicated family life. Michael Collins, left to his own devices in the lunar orbiter while his two colleagues walk around on the surface below, drifts off into some bizarre ’60s-inspired rock ‘n’ roll fantasies.

The book’s artwork is gorgeous. One of the qualities of comic books about space is the sheer depth and profundity that is required in panels which are overwhelmingly dark. As opposed to the bright colours of many earth-bound comic books, in order to succeed, a comic book about space needs to adopt an opposite approach, accepting the overwhelming concentration of dark, black panels and recognizing that artistic success lies in the sparing use of colour to offset the darkness of space. Apollo succeeds brilliantly at the task; the space panels are gorgeous and the delicate insertion of light and colour into these panels echoes the cosmic insignificance of humanity’s space machines, inserting themselves into the vast darkness of space. The test of a comic about outer space lies in whether it stirs the imagination with the sweeping grandeur of its cosmic canvas, and Apollo succeeds magnificently.

The book doesn’t shy away from the question of how to balance humanity’s Utopian desires to explore space with its baser instincts. In Apollo, it’s handled allegorically, with US President Richard Nixon (1969-1974) acting as the personification of everything that is base and ignoble about humanity. He was the sitting president when the moon landing took place—the unworthy recipient of the glory resulting from the hard work and dedication of previous administrations—and he fully plays the part of the inept fool. He has to be told what to say, is overly concerned about petty trivialities, and consistently fails to grasp the real significance of humanity’s achievement in landing on the moon. He personifies all the negative elements that hold humanity back, and wallows unconcernedly in that negative space; while the astronauts—for all their personal faults and very human weaknesses—represent the quality of striving to surmount those weaknesses and reach for something better.

This matter of seeking purpose and direction in space exploration presents a very fundamental question today, when the future of space exploration is threatened not just by budget cuts and greedy generals who would prefer to build explosive rockets over exploratory ones. The greatest counterweight to those obstacles is an enthusiastic public, and much of today’s public has been turned skeptical by the naysayers. Inspired by John F. Kennedy’s virtue-laden speeches (1961-1963), the American public—and much of the world—was catalyzed in the ’60s by the quest to land a human on the moon. It’s that sort of public enthusiasm that space exploration needs to regain. It’s fitting, then, that the approach of the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, July 2019, should be filled with books and films on the topic. We need reminding, it seems, of what we can accomplish when we aren’t absorbed in our narcissistic luxuries or blowing ourselves to bits. What better way of reminding us what our species is capable of achieving when we dedicate ourselves to a noble task?

So bring them on—all the books, all the films, all the reminders that humanity has a collective soul that yearns to strive for greatness, all the reminders of what we are capable of accomplishing as a species. Apollo offers a beautiful and stirring contribution toward this task.