RKO Classic Romances and RKO Classic Adventures are two new Blu-rays from Kino Lorber that showcase a festival of nicely restored talkies whose virtues come across more clearly, due to the visual and audial scrubbing. More than simply historically important, these movies are also engaging and revealing, especially when seen together.

RKO owed its existence to the talkie revolution. RCA went looking for a film company to exploit the patented Photophone sound-on-film process, developed by RCA’s parent General Electric, while the established studios were already aligning with a rival process. RKO was born from the merger of a small studio owned by Joseph P. Kennedy (yes, the President’s father) and a theatre circuit. All the films in these two sets date from 1930 or 1931, and were produced either by RKO’s Pathé subsidiary or the main studio, originally calling itself Radio Pictures under producer William LeBaron before David O. Selznick took over the company in October 1931.

The five movies in RKO Classic Romances highlight a parade of now-forgotten leading ladies who specialized in what the industry called “women’s pictures”. These movies explored the basic choices available to women regarding marriage, careers, sex, and children, and always occupied themselves with defining and searching for love. Since they’re all “pre-Code” films dating from before the Production Code crackdown in 1934, they have a frankness about sex that became impossible later.

John Francis Dillon’s Millie (1931) is a vehicle for Helen Twelvetrees, a stage-trained actress who came to Hollywood and enacted lots of suffering, of which she had a fair bit in her own life. Her most famous film that’s known best to connoisseurs is Tay Garnett’s Her Man (1930). Millie derives from a 1930 novel by Donald Henderson Clarke, who had a line in romances about modern successful women who have sex without marriage until they wise up. A more revved-up version of the same idea was his 1933 novel, Female, filmed that year with Ruth Chatterton.

Millie opens with a lively small-town girl being sped around in her boyfriend’s car, and the rest of the plot will be more or less as speedy. The chorus of boys at the malt shop declare her a pip and a peach who “knows how to take care of herself”. Millie says she wants to see the world, but when Jack (James Hall) asks if she’ll come to New York with him, she says that’s one thing she won’t do.

The unspoken implication is sex before marriage, but he clarifies with a proposal. A quick glimpse of a Justice of the Peace sign leads to a hotel room where Millie trembles and calls her mother for reassurance. One minute later, Millie has a three-year-old child (subject of a 1947 sequel, Millie’s Daughter) and a beautiful mansion, but she thinks Jack doesn’t love her anymore because he doesn’t kiss her like he used to and just comes home late and falls asleep.

He says he hasn’t got time to argue and departs for a sudden business trip while Millie receives a call from old chum Angie (Joan Blondell), who’s sharing a bed with roomie Helen (Lilyan Tashman) in their nighties while the landlady waits for the rent. The movie keeps implying that Angie and Helen are, if not prostitutes exactly, at least not far from it. Tashman specialized in the kind of sharp, modern, hard-bitten, been-around gal that Blondell would soon specialize in, although here Blondell is only apprenticing as a slightly dizzy blonde. They’re this movie’s fresh air.

Before you can say “so this is your business trip”, Millie spots hubby with a tootsie in some joint of daytime assignation where she’s lunching with Angie and Helen. One blink later, she’s divorced, having given up custody of her daughter to the swanky mansion (“it wouldn’t be fair”) and refused a “pay-off” so she can work for a living, to the astonishment of the gals. This shows she’s on the square, or maybe just square.

If you can believe this, you’re ready for the rest of an eventful plot in which once-burned Millie makes her way up the business ladder while refusing to marry the guys she likes enough to sleep with. We’re hardly halfway through a story that involves a suave banker (John Halliday), Millie’s now-teenage daughter (Anita Louise), and a murder trial, all achieved in under 90 minutes.

This was an era that didn’t waste time, and also when women who strayed from the straight and narrow were constantly giving up children and having murder trials, although Millie’s troubles began with marriage to a louse who’s depicted as boringly typical. One element separating this film from, say, Madame X (1929)–and this may be a spoiler–is a happy ending of the type that wouldn’t be permissible in a few years.

New York is depicted as a world of cheating husbands, restless wives, women of easy virtue, the possibility of a reasonable career, and everyone on the make, far from Millie’s small-town values. Thus do stories like this negotiate “modern” options with traditional morality, twisting life into knots to show that women of all classes get the short straw. From The Plaything of Broadway (1921) and Flaming Youth (1923) to Call Her Savage (1932), director Dillon had a long line in such paradoxical crucifixions and celebrations of American womanhood.

(IMDB)

A lighter affair is Lloyd Bacon’s Kept Husbands (1931), essentially a marriage comedy in which a spoiled socialite (Dorothy Mackaill of Safe in Hell) sets her cap, as who wouldn’t, for a young architect played by Joel McCrea at the beginning of his career, when he was not only handsome but beautiful. As presented at a tight clip by Bacon, who specialized in tight clips, the whole story involves waiting to see how much hubby will take before he asserts his manly pride and insists on taking control of his career and marriage. What’s most important, you see, is that husbands not be emasculated into poodle-carrying lackeys who sacrifice their careers for their spouses, although wives should expect the vice to be versa.

Helping greatly is their chemistry, the likability of her father (Robert McWade), and the tender relationship the couple has with the groom’s mother (Mary Carr), who loves them both and explains the philosophy of the title — that there are many ways of keeping a husband. On his wedding day, the groom gives his mom a surprisingly emotional kiss.

Third-billed is Ned Sparks as a sourpuss who stands around uttering phrases like “What’s cavy-aire to the few is applesauce to the gander”. There’s certainly a lot of applesauce to go around, yet the screenplay deftly avoids some of its most telegraphed pitfalls, such as in the scene where the heroine rescues herself from a masher by quoting old melodramas. The film prefers to present characters who care about each other, and that’s ingratiating.

(IMDB)

George Archainbaud’s The Lady Refuses (1931) has yet another young man who could be a brilliant architect if he’s not mixed up with the wrong woman, and yet another murder tossed in at the eleventh hour. Betty Compson, one of the few major silent stars who made the transition to talkies, plays desperate down-and-out June, who walks the foggy London streets on her first night of trying to be a common–everyone halts before they say the word, so we can fill it in ourselves.

She’s rescued from London bobbies by Sir Gerald (Gilbert Emery), who takes a notion to hire her to woo his pup of a son (John Darrow, overacting), always staggering drunkenly in his tux with one curly lock over his forehead, from the clutches of a gold-digger (Margaret Livingston) and her jealous Russian lover (Ivan Lebedeff). The general thrust is that father and son both fall for June, and she prefers the father, but all gets muddled into a bit of a sticky wicket while June deplores “this righteous code that gentleman have”. Everyone swings between jealousy and sacrifice before the ambiguous ending.

The most interesting contributor to this item is screenwriter Wallace Smith, a now-forgotten novelist, journalist and illustrator most noted for working with Ben Hecht. Smith provided the Aubrey Beardsley-esque illustrations to Hecht’s controversial novel Fantazius Mallaire (1922), and a later novel by Smith about a prostitute faced legal troubles in England, according to Wikipedia. The source story for this film comes from Robert Milton and famous musical-comedy playwright Guy Bolton; nothing could seem further from his output than this story, which really should have been handled as a musical comedy.

Films of this era typically have little or no background score; this one goes without, which helps it feel stiffer than it really is. The extremely prolific Archainbaud was making a lot of RKO films at this time, most famously the following year’s stylish thriller of class and race revenge, Thirteen Women.

Another father-son triangle marks The Woman Between (1930), possibly the best film in the set. It’s certainly the best staged, as director Victor Schertzinger and photographer J. Roy Hunt use lengthy takes amid a complex mise-en-scène, gliding in all directions across rooms and sections to maintain visual interest. Since Schertzinger was prolific as a composer as well as a director, he pays great attention to the use of music in a film made when mixing multiple tracks wasn’t yet possible. (IMDB)

The opening credits combine both qualities. The camera dollies forward and swings around to present a woman reading the credits in a newspaper while music plays loudly, and then another character comes in and asks “Do you mind if I turn this off?” before switching off the radio. What we’d thought was background score was actually diegetic, as will be more examples in later scenes, and all the music was probably played live during the shoot.

All these Radio Pictures feature scenery and costume design by the same person, Max Rée. It’s interesting to see costumes and sets so coordinated, and here he knocks himself out with the massive Art Deco sets and the stunning gowns for Lili Damita, another silent star who bridged the talkies and looks drop-dead fabulous, whether in mannish cuts with floppy hats or more ethereal creations. Schertzinger even gives her a song, moaned in Dietrich mode. Savvy character detail: although Damita’s heroine is the chic-est woman in town and runs her own French dress shop, she’s introduced playing on the floor with a toy and chatting with the black elevator operator, thus proving she’s unpretentious and down to earth.

Howard Estabrook’s script, adapting a play by Irving Kaye Davis, balances an absurdly scandalous coincidence with intelligence, making all the characters credible and likable. Handling it almost as a comedy, the film presents a situation where a glamorous stepmother (Damita) unwittingly falls for the man she doesn’t know is her aged husband’s long-lost son, who stormed out in a snit when dad announced his second marriage. After titillating us with the implication that wife and stepson had a shipboard romance, the last reel clarifies that she’s refused to be physical with him so far.

In typical “women’s film” manner, the story hinges not so much on particular actions as on the existential dilemma presented by having a choice: the besotted husband or the youthful son? Where does one love? One could call the result much ado about nothing, yet it’s cleverly done and satisfying as it finally affirms the sanctities of marriage by a feather’s breadth. Estabrook’s script is smart enough to know that it’s impossible to satisfy everyone and that all must live with their choices. At their best, this is part of what makes these “dilemma” scenarios so fascinating.

Lester Vail plays the impetuous young chap, O.P. Heggie is the husband/father, Miriam Seegar the spoiled and suspicious daughter, and young Anita Louise from Millie is a hopeful girlfriend, but you’d better believe this is Damita’s show. Her French accent doesn’t get in the way, and she’s a heck of a clothes horse. She makes you understand what all the fuss is about. Although Damita is probably best known today as Errol Flynn’s wife, this restoration could easily spark interest in her forgotten silent career with many illustrious directors. We can dream.

Poster excerpt (IMDB)

The set’s last film is also its earliest, lightest, and most sophisticated. Paul L. Stein’s Sin Takes a Holiday (1930) stars the busy and popular Constance Bennett, another major star now almost totally forgotten. She’s charming and natural as a smart, self-effacing, bemused heroine with a smoky voice and blonde helmet. Legal secretary Sylvia Brenner moons for her boss (Kenneth MacKenna), but that’s the film’s only obvious cliché. He’s a divorce lawyer who runs with a pack of adulterous and serial-divorcing gadflies in New York, and in order to divest himself of a clingy mistress (Rita Le Roy), he fixes up a sham marriage to Sylvia.

When Sylvia departs for Paris, she spends time with the most sophisticated devil of the bunch, played by Basil Rathbone with all his Rathbonage, halfway between oily villain and dashing catch. Sylvia gambles that rumors about them, plus her Paris makeover, will snag her in-name-only husband’s attention, and she’s not wrong. He’s not really worthy of her, but he’s the one she wants; maybe it’s his curly hair. What’s interesting, pre-Code-wise, is that she doesn’t care a whit about his rampant experience nor that she’s the only one in the movie not sleeping around.

Horace Jackson’s script pulls off that special kind of Hollywood paradox: an unbelievable premise handled in a credible manner. It all depends on Bennett’s warmth and magnetism, with nice support from ZaSu Pitts as a buddy. John J. Mescall’s camera work features graceful dollies forward and back. As a director, Stein made his mark in the silent German industry before coming to Hollywood and eventually settling in England, so he was a thorough professional who handles this fluff with the proper lightness.

The companion release is RKO Classic Adventures, containing three melodramas fashioned for a male audience. In other words, they focus on men who commit various two-fisted actions, and they’re inherently less believable than the women’s melodramas.

For example, the crime film is The Pay-Off (1930) starring and directed by Lowell Sherman, who specialized in dapper playboy-villains of the type seen here. The film belongs to the early strain of gangster talkies that exploited the public’s fascination with the new kind of criminal spawned by Prohibition, and which Warner Brothers and Universal would take into more action-packed directions, pushing screen violence to a point that contributed to the Production Code crackdown.

Sherman’s eye-shadowed protagonist leads a double life as a society swell and the leader of all the gangs in town, although he draws the line at murder. When circumstances throw a naive young couple (Marian Nixon, William Janney) in his way, he “adopts” them and showers them with gifts while suddenly planning to go straight, although things don’t work out that way. In the first scene, the green fools are planning to marry tomorrow but somehow never get around to it over weeks of largesse, so they’re sitting around waiting to be suckers for a rival dandy (Hugh Trevor) who exploits them in a robbery.

The plot, as scripted by Jane Murfin from the 1927 play Crime by Samuel Shipman and John B. Hymer, is so incredulous from set-up to wrap-up that the dialogue is obliged to make a self-conscious reference to “the fiction writers”. That didn’t stop RKO from remaking it as Lew Landers’ Law of the Underworld (1938).

The credits include Lynn Shores as “Pictorial Director”. IMDB seems to believe that places him in the art department, but I doubt it; that was Max Rée, who gets much higher billing and was totally in charge of design and costumes. I believe Sherman attended to the actors and left the camera placements to the “pictorial director”, and that wasn’t too rare in early talkies. Sherman was hitting his stride as a director with the scandalous 1933 items She Done Him Wrong with Mae West (another reason for the crackdown) and Morning Glory (which won Katharine Hepburn an Oscar) when he died in 1934, taking the pre-Code era with him.

We mentioned above that director George Archainbaud and writer Wallace Smith fashioned The Lady Refuses. Their previous collaboration, the handsome and expensive-looking The Silver Horde (1930), derives from Rex Beach’s 1909 novel, but its more direct source is a 1920 film version being remade here as a vehicle for the above-named Joel McCrea. The title refers to salmon, for our heroes are rugged men who show up in Alaska by dogsled and resolve to make their fortune in fish. Repeating Ned Sparks: “What’s cavy-aire to the few is applesauce to the gander.”

McCrea plays Boyd, a busted prospector who blows into an Eskimo or Inuit village with George (Louis Wolheim), a shady comic-relief partner he picked up on the trail. They’re put up by Cherry Malotte (Evelyn Brent), who pulls strings to encourage Boyd’s cannery business in rivalry with stop-at-nothing scoundrel Marsh (Gavin Gordon). The naive Boyd doesn’t know what everyone else does: Cherry’s a prostitute who sleeps with the banker to seal the deal.

The movie posits, along with most other Hollywood movies, that capitalist rivalry equates to romantic rivalry, for both businessmen want to marry society “namby-pamby” Mildred (an early role for Jean Arthur, already pert), a banker’s daughter and therefore not only spoiled but symbolic of spoils.

The script contrasts the way men settle things (with violence) vs. the way women settle things. Thus, a contract gets settled when Boyd has a big bare-chested fight with a foreman. This sequence appears to have been shot with an undercranked silent camera, because it’s slightly sped up.

All the fishery stuff is very attractive, and McCrea justifies his leading-man promise. Nevertheless, the film is at its most gripping during those moments when it flips to being a woman’s picture from Cherry’s viewpoint. Brent, another silent star who made the talkie cut, is terrific and unforced as one smart tough cookie. The dialogue continually affirms her “all rightness” in gender-crossing phrases like “one of the guys” and “man to man”. When Boyd finally realizes she’s “that kind of a woman”, George says “What of it? Does that keep her from being a regular fella?”

Her big scene is a confrontation with Mildred in which she fires off: “I’m Cherry Malotte. They know about me from San Francisco to Sitka. My reputation’s got marks on it I couldn’t rub off if I wanted to. I am what I am. I don’t know how they finally settle things in this world or the next, but when the day comes, I’ll stand there with my chin up and take what’s coming to me. And I wouldn’t trade places with you, you white-livered, sweet-smelling hypocrite, if they gave me a one-way ticket to hell!”

Thus the movie plays with class and the moral standards associated with it, asserting that one class is hypocritical while the “regular fellas” are “all right”. In his choice of women, Boyd will have to re-adjust what he’s been taught to believe. The film resolves with at least two decisions that wouldn’t have been acceptable after 1934.

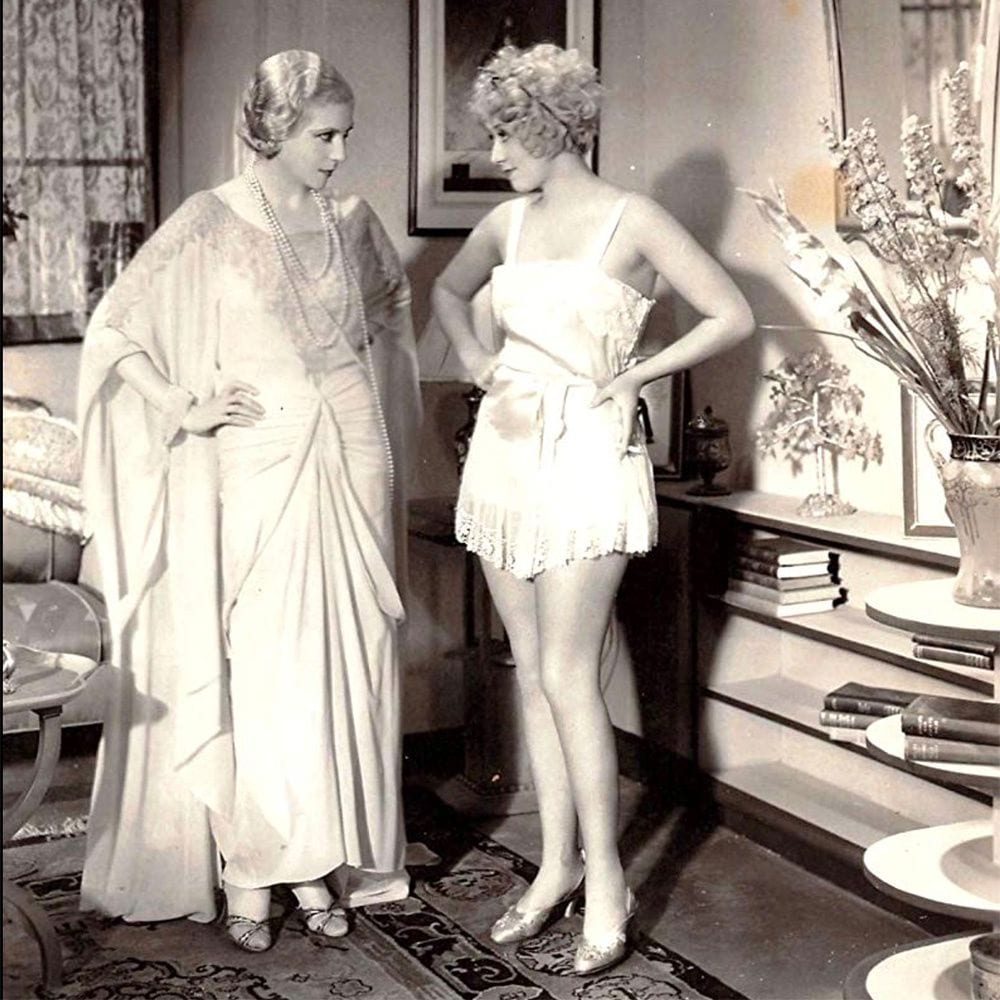

Also appearing are Raymond Hatton as a lunk who’s both comical and scary, and major silent star Blanche Sweet as Queenie, a tipsy prostitute seen lounging in her frilly underthings. When Cherry observes that Queenie didn’t use to smoke, she replies, “Oh, I’m going to the dogs something terrible.”

The other film in this package, and the one featured on the cover, is Howard Higgin’s 1931 Pathé western The Painted Desert, starring William Boyd before he became known as B-western star Hopalong Cassidy. Shot in 1930 by Edward Snyder, mostly on location in Arizona, this poses the characters picturesquely against beautiful vistas and includes camera movement not only to follow characters walking but even riding, with at least one shot from atop a stage wagon. In this case, the absence of background score accentuates the sense of reality.

The story opens with two old galoots, Jeff Cameron (J. Farrell McDonald) and Cash Holbrook (silent western star William Farnum), rescuing a baby boy from a broken wagon, so it’s not unlike the premise of Peter B. Kyne’s 1913 novel The Three Godfathers, whose multiple filmings began in 1916, except that it’s only two godfathers.

Their friendship turns to enmity as Cash adopts the baby, who grows up to be square-dealing Bill (Boyd), determined to repair the bond between the stubborn old men by proving they still love each other. Male bonding is the theme, even with a tossed-in romance with Mary Ellen (Helen Twelvetrees of Millie, not doing much). Holding back their emotions, men are frequently almost touching hands until Jeff and Cash finally grasp hands in close-up behind Bill’s back, where nobody can see except the audience.

The show was kind of stolen by Clark Gable in his talkie debut as a stranger who turns out to be responsible for instigating all the trouble. He’s so tall and strapping and young, he has to hunch over next to Boyd, but he still made an impression on audiences with his growling voice. He looks good just brooding on a fence.

The most salient problem with the film today is odd editing that omits the most exciting bits of action, which are reported from offscreen. According to Leonard Maltin’s Classic Movie Guide (2005), the action was clumsily chopped out for recycling in the 1938 remake. Maybe somebody needs to see about re-inserting it.

All or most of these films have fallen into the public domain and circulated in less than ideal condition. These Library of Congress prints have been digitally restored by Lobster Films in Paris and consistently look and sound very good. It’s smart to gather them into sets because, while no one film is important enough to fly on its own, the cross-section makes an attractive bargain of movies that comment on each other while illuminating their era. It would be fantastic to see a similar set devoted to the studio’s early musicals and two-strip Technicolor experiments, but that’s probably a pipe dream.