It should come as no surprise that the obituaries for legendary film director Billy Wilder have displayed a remarkable consistency. When a successful figure lives into his 90s, as did Wilder, his public image becomes fixed into a permanent portrait. To the movie maven, Wilder was the last of his kind, the most visible link to the Golden Age of Hollywood. Honored with frequent awards and encomiums, he epitomized the professional spit and polish that the factory system of the major studios promoted.

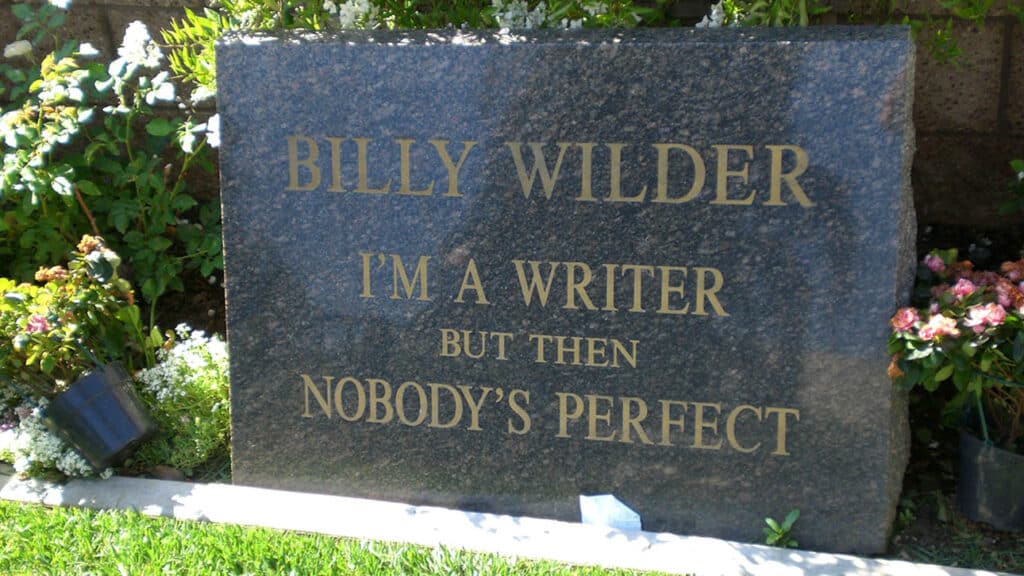

An old-school believer in the primacy of the word and the utility of the image, Wilder outlived the emergence of more fashionable forms of presentation and became the touchstone for a kind of worldly wisdom that did not condescend to the mainstream audience. If he rankled at his early and extended retirement, and financiers’ failure to bankroll one more movie, Wilder remained an artist Hollywood could revere as the epitome of certain venerable if rarely achieved, ideals.

In a community that prizes team players, Wilder remained a maverick despite being a member of a most elite club. Wilder possessed, in the words of his biographer Ed Sikov, “the fastest, funniest, meanest mind in Hollywood.” He exercised his wit without censorship upon his profession and his peers. Little fazed him about either fame or failure. “Medals, they’re like hemorrhoids,” he remarked. “Sooner or later, every asshole gets one.” When he met with Sydney Pollack, who in 1995 remade Wilder’s Audrey Hepburn vehicle Sabrina (1954), he compared the number of their respective Oscars (Wilder’s six to Pollack’s two), and dismissed Pollack’s commercially successful Out of Africa (1985) as “classy but boring.”

Amusing as it is to dwell upon such anecdotes, Wilder was more than the cocktail-consuming, zinger-dispensing sophisticate who regularly punctured the balloon of convention. First and foremost, and as much as we associate Wilder with spurning sentimentality, his movies time and again pull their punches in the final reel. Andrew Sarris refers to it as the “cancellation principle” in Wilder’s work. For example, in Double Indemnity (1944), hardboiled dame Barbara Stanwyck shoots Fred McMurray once but then drops her gun, her homicidal intentions interrupted by a final pang of affection. In Ace In The Hole (1951), Kirk Douglas’s ruthless reporter rediscovers his lost ethics when the man whose story he’s milked for all its worth, dies. Or, Jack Lemmon’s con artist, in The Fortune Cookie (1966), leaps out of his wheelchair in defense of a friend, thereby putting the kibosh on an elaborate insurance scam.

Perhaps Wilder felt compelled to pull back from the brink, to make the “bitter pill” of his social commentary easier for his audiences to swallow. Or maybe he realized that successful box office required the soft-peddling of his personal point of view. Whatever the case, his outrageousness never succumbed to out-and-out nihilism. Even the cruelest of Wilder’s characters eventually pay for their misdeeds. His films may incorporate some of the most skeptical and scathing images of American small-mindedness and stupidity, yet he regularly redeemed his characters before the final credits.

Wilder has been celebrated for his urbane characterizations, yet he rarely created a well-rounded figure in his films. More often, he played opposing types off one another, typically a wiseass and a wimp. This pattern appears in the Tony Curtis/Jack Lemmon pairing in Some Like It Hot (1959), as well as the three pictures that joined Walter Matthau with Lemmon: The Fortune Cookie, The Front Page (1974), and Buddy Buddy (1981). He treated women characters similarly, pitting the elegant Marlene Dietrich against the mousy Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair (1948), going out of his way to make the attractive Arthur look uncommonly plain.

This practice might have resulted from Wilder’s temperamental incapacity to commit to a broad-minded perspective of human behavior. It is worth noting in this context that he always collaborated upon his screenplays, and co-workers noted the contrast in personalities between him and his colleagues: the patrician Charles Brackett and the less aggressively acerbic I.A.L. Diamond.

On the other hand, when Wilder committed himself to a strong, if a somewhat monodimensional figure, the results were powerful. Gloria Swanson’s self-absorbed madwoman in Sunset Boulevard (1950) is famously riveting. Less well-known but equally overwhelming is Douglas’s bile-soaked reporter in Ace In The Hole. The film was one of Wilder’s most notable commercial failures, yet it is hard to imagine he assumed that the public would accept his image of them as mindless voyeurs, obsessed with calamities and scandals. Few pictures — not even Elia Kazan’s A Face In The Crowd (1957) or Sidney Lumet’s Network (1979) — can equal Ace In The Hole‘s dissection of the news industry’s pattern of chewing up its subjects and spitting them out for consumers with short attention spans.

Each obituary I have read details how Wilder fell out of commercial favor with Hollywood in the 1980s, unable to finance a picture during the last twenty years of his life. Each succumbs to the common wisdom that his last several films were not only box office failures, but also lapses of skill and intelligence, as his age and temperament increasingly excluded him from his audience. I beg to differ with that assessment, for two of those late pictures hold my interest more fully than a number of their more renowned predecessors. Part of their wistful appeal lies in the cynical Wilder’s surrender to something approximating sentiment, and his interest (understandable, considering his age at the time) in our common mortality.

The first, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, released in 1970, in part reflects the period’s tendency to mock its idols and reveal their feet of clay. Wilder deviates from the customary depiction of the detective (played dispassionately by Robert Stephens), by presenting him as a lonely misogynist whose lauded powers of deduction are betrayed by a woman who proves to be a foreign spy. Holmes mistakes one clue after another, only to have his brother, Mycroft (Christopher Lee), correct his errors and tidy up the damage: he sees to it that the foreign agent Gabrielle Valledon/Ilsa Hoffmannstahl (Genevieve Page) is returned to the German government. When Holmes discovers in the final sequence that she has been executed for espionage, he locates the cocaine that Dr. Watson (Colin Blakeley) keeps hidden, shuts himself behind closed doors, and medicates away his sorrow. No final quip or caustic riposte accompanies the plaintive image of inconsolable sorrow.

Even more commanding is Wilder’s altogether underrated Avanti! (1972). Superficially a bedroom farce, it incorporates what is for the director an unaccustomed appreciation for the pleasures of the flesh, the beauty of the physical world, and a fleeting liberation from the taxing demands of social custom. The central character is an uptight businessman, Walter Armbruster Jr., played by Wilder’s Everyman, Jack Lemmon. Called suddenly to the isle of Ischia to recover the body of his late father, he meets a polite and notably plump Englishwoman, Pamela Piggott (Juliet Mills), who has come to claim her dead mother. At first, she serves as little more than the object of Armsburster’s ham-fisted fat jokes and recurrent Ugly American diatribes about the insufficiencies of foreign culture.

The eventual revelation that the two corpses were longtime lovers who met each year on Ischia leads to a recapitulation of their relationship on the part of Walter and Pamela. She gains a lovely glow as the affair develops, which in turn deflates his high-velocity chatter and results in one of the least common plotlines in contemporary Hollywood film: a believable and sensual relationship between middle-aged adults. Not that Wilder altogether dispenses with out-and-out-farce and tomfoolery, for Avanti! includes what is likely one of Lemmon’s only nude scenes, a charming skinny-dipping escapade in the clear waters off Ischia.

And Avanti! is not without its liabilities. It’s a little too long and more than a little slow, but that can be forgiven. Wilder has seldom been so relaxed as he is here, or as able to reveal interest in life’s simple joys. However, as much as anything, what lingers in my mind about the film is a brief shot when Walter and Pamela visit a local chapel to view the bodies of their respective parents. Wilder, by and large, believed camerawork ought to be little more than utilitarian: words first and images second. But here, the director of cinematography, Luigi Kuveiller, permits some exterior light to enter the church through a window and bathe the scene with glorious luminescence. How uncommon for Wilder to include such a shot, and how delightful. For once, no wisecracks, no pratfalls, and no snide annotations. In that brief moment, the cynic embraces his repressed sentimentalism, and he breaks your heart.