The first stop for many reflecting on the literary career and staggering artistic legacy of Philip Roth after hearing of his recent death was the easiest and most convenient choice. Roth’s 2004 novel The Plot Against America illustrated a strange alternative history in which a fascist Charles Lindbergh defeats Franklin Roosevelt in a staggering landslide in the 1940 Presidential election. What follows is an appeasement with Adolph Hitler, an “understanding”, and a relocation of American Jews to the western United States. It’s an intense series of events in a concentrated time period that plays as both fantasy and disturbing possibility. The most logical comparison was with Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here, yet where Lewis was comfortable with the exaggerated hyperbole of his fascist fictional hero “Buzz” Windrip defeating Roosevelt, Roth succeeded by staying calm and level-headed:

Fear presides over these memories, a perpetual fear.

Focusing on Roth’s late-career masterpiece (he published his last novel in 2010 and shortly afterwards announced his retirement) is understandable and almost feels like déjà vu. Talk about The Plot Against America re-surfaced in a great way since the 2016 election of Donald Trump, whom Roth described in a January 2017 New Yorker exchange as “a simple con man”. It was a suitably subtle appearance by the grand literary lion, e-mail responses to questions from writer Judith Thurman:

All I do… is… defatalize the past.

Later, in a succinct take-down that could only come from a writer who came on the scene in 1959 with the story collection Goodbye, Columbus and gave his swan song in 2010 with Nemesis, Roth isolated Trump within the context of a literary device whose purpose is only to serve the needs of the plot:

It isn’t Trump as a character, a human type… the callow and callous killer capitalist-that outstrips the imagination. It is Trump as President of the United States.

The fact that Roth received every literary recognition in his lifetime save for the Nobel Prize in Literature might not mean much in the light of that committee’s current problems. Nevertheless, a sense of bitterness remains for those of us mourning the loss of this final great literary lion of the 20th century. Norman Mailer and John Updike were multiple Pulitzer and National Book Award winner. Saul Bellow won his Nobel in 1976. These lions roared about the national condition and cultural identity (or lack thereof) through a tangled web of national and international events. The past collided with all these lions, all these dead white masters who worked in an environment free from #MeToo or Black Lives Matter movements. They clashed quite often with the “other” (a non-white world), and their work suffers in retrospect, but the canon of Philip Roth (with gender issues a major exception) remains relatively free from political incorrectness.

Take a step beyond The Plot Against America and the Roth catalog becomes even more impressive and daunting. His writer hero Nathan Zuckerman was an apprentice to an older master in 1979’s The Ghost Writer, entranced by a girl who believes herself to be Anne Frank, not a reincarnation but the actual martyred teen Jewish diarist, alive to tell the tale. This ultimate representation of female Jewish identity should be enough to validate Nathan in his parent’s eyes, but nothing is ever good enough. Nathan makes his final appearance (of nine) in 2007’s Exit Ghost, but it’s the aching heartbreak of 1997’s American Pastoral that stays longest with the reader. Nathan is again an observer, commenting from the sides, looking at Seymour “The Swede” Levov and the magic of a life well-lived as an invincible youth. It’s the ache of loneliness and purpose that resonates strongest here:

You fight your superficiality, your shallowness… what are we to do about this terrible significant business of other people… The fact remains that getting people right is not what living is all about anyway. It’s getting them wrong that is living… That’s how we know we’re alive: we’re wrong.

Roth played with time, possibilities, and the essence of true characters. Roth’s greatest character, at times, was Philip Roth, especially in such memoirs as 1988’s The Facts: A Novelist’s Autobiography and 1991’s Patrimony: A True Story. This ongoing process of determining place as a man, as a writer, as a cultural observer, meant that at times things got tangled. The sexual, scatological, outrageously funny Jewish guilt themes were in full display in 1969’s Portnoy’s Complaint, in which the sex scenes overwhelmed something deeper, something more profound:

I am marked like a road map from head to toe with my repressions. You can travel the length and breadth of my body over superhighways of shame, inhibition, and fear.

When She Was Good (1967), a lesser Roth novel, served as an interesting prop in the “American Bitch” episode of Lena Dunham’s HBO show Girls (season 6, episode 3). While most interactions between the four leads and their partners were insufferable, this episode was a two-hander in which Hannah Horvath (Dunham) spends the entire running time discussing literature with one of her favorite writers, Chuck Palmer (Matthew Rhys), a confessional novelist with a troubling abusive reputation regarding women. Hannah is despondent that the true character of the man might have a negative effect on his artistic legacy. It’s a tightly controlled teleplay in which relationships and the line between adhering to reality and obliging fiction is discussed. Palmer gives Hannah the Roth novel (about a do-gooder woman who helps men) before he literally (and figuratively) reveals himself to her. It might be giving Dunham too much credit that she’s communicating with Roth in this episode, but the effect (especially by the end) is chilling.

On the day Philip Roth died, PBS premiered its new eight-episode documentary series The Great American Read, in which 100 novels, memoirs, book series, and children’s books are discussed by a variety of writers and stars. The literary advisory panel includes members of the National Book Foundation and the Author’s Guild. The American Public had its say as well, which might be one of the reasons this list is so wrong-headed. The series plans to introduce the titles in theme episodes such as “Heroes”, “Villains and Monsters”, “Other Worlds,” and “What We Do for Love”.

What is the problem here? Will we now segue into a diatribe against populism and in favor of strictly the academic and high-minded? Examine the facts here and reach your own conclusions. Approximately 25 percent of the titles are written by non-Americans. This is not about ethnocentrism so much as definition. What is an “American” read? The idea of “great” is the ultimate subjective conclusion, but at least “American” should be determined by geographic birth of the author. Ideology and perspective be damned, an “American” is easily identifiable.

The other major problem is that some titles included have absolutely no place in any list of “great” anything: Fifty Shades of Grey (series) by E.L. James, Left Behind (series) by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins, The Twilight Saga (series) by Stephenie Meyer, and Alex Cross Mysteries (series) by James Patterson. There are other major problems. Kurt Vonnegut is represented by Sirens of Titan. The tired old warhorse of J.D. Salinger’s Catcher In The Rye is still hanging on to relevancy, and Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind, an unapologetic love epic to American slavery days, somehow has staked a claim here. There’s no Ray Bradbury, no John Updike, no Saul Bellow — and no Philip Roth. As an entity that will surely entertain viewers and perhaps promote some sort of literacy in these troubled days of short attention spans and poor impulse control, this list will meet some sort of need. Take it as a parlor game in which talking heads will wax poetic and opine about how their chosen titles changed their lives, and it will serve a purpose. Take it as a real account of great American books, and it’s meaningless.

Perhaps there will be a resurgence of interest in and appreciation of the works of Philip Roth in these immediate days after his death. Certainly he could have been better served than the dreadful 2016 version of American Pastoral. A 1984 TV adaptation of The Ghost Writer, for American Playhouse was suitably quiet and reflective. A full appreciation of a writer’s skills cannot really be captured on anything but the page, and Roth knew that. “I turn sentences around,” he wrote in The Ghost Writer. “That’s my life. I write a sentence and then I turn it around. Then I look at it and turn it around again.” That should surely be the true mission statement for any Great American book. It’s a work ethic that understands the real truth about artistic achievement in writing. Anything that hopes to achieve brilliance needs to have been written once, again, and again once more. It never stops.

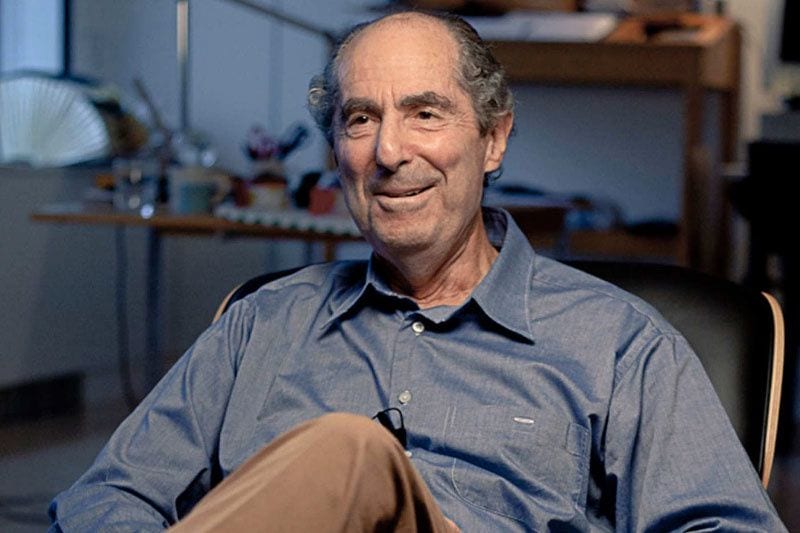

- A Remarkable Portrait of a Reclusive American Treasure: 'American Masters Philip Roth: Unmasked' - PopMatters

- Exit Ghost by Philip Roth - PopMatters

- Philip Roth -- Welcome to the Canon - PopMatters

- 'American Pastoral' Is Yet Another Lifeless Philip Roth Adaptation ...

- 'Girls': An Engrossing "American Bitch" Just Misses Transcending Its ...