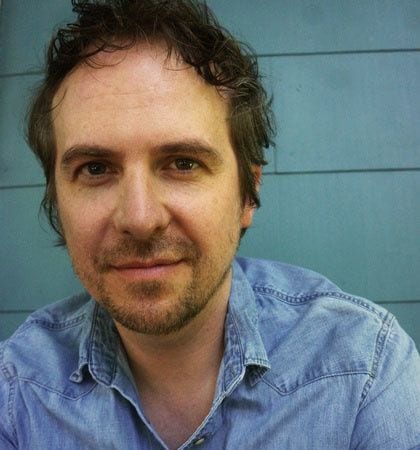

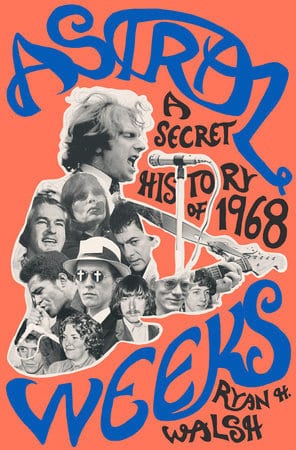

With the publication of Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968, author Ryan Walsh is experiencing the kind of success aspiring authors can spend their lives dreaming about. Not only is his debut book out with a major publisher, Penguin Press, but articles in Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, Mojo, The New York Times, PopMatters, and dozens of other publications, have greeted its arrival. That kind of attention might go straight to some people’s heads but when I talk with Walsh over coffee in San Francisco, where he’s visiting for a reading at the city’s Green Apple Bookstore, he seems to be taking it all in stride. He remembers, for example, that when the deal with Penguin became certain, “it was like, all of a sudden, I felt like I was in a movie. I was standing outside in the rain. I instantly called my wife (Walsh is married to musician Marissa Nadler). I’ll never forget it.”

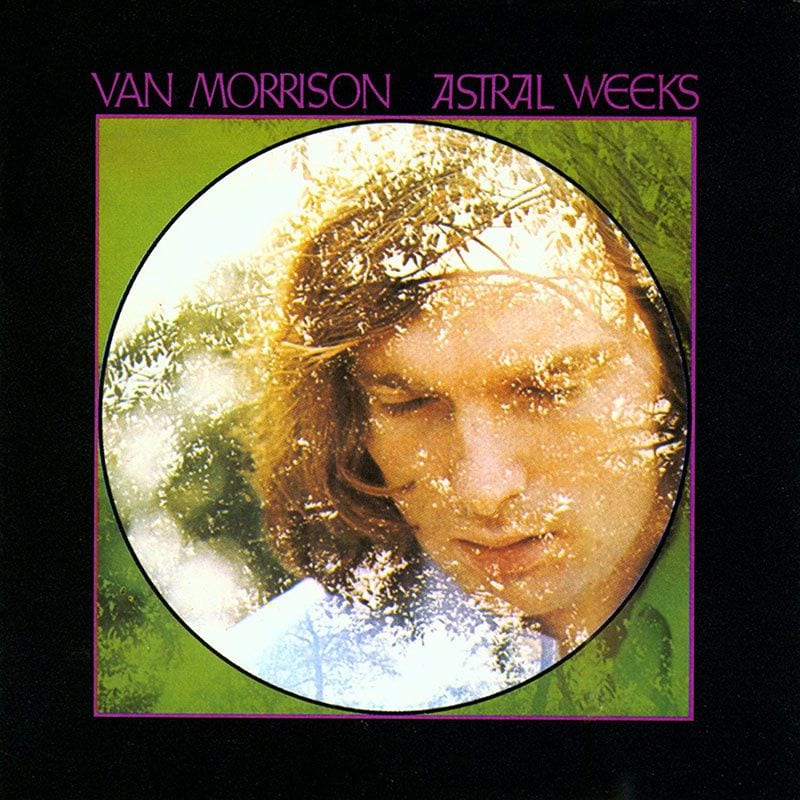

Walsh’s Secret History of 1968 is a breakdown of the titular year into a dozen or so stories. They inform and bounce off each other, and all share a center in Boston, Massachusetts; Walsh’s hometown. Taken together, these different pieces form the atmosphere in which Van Morrison was working and living while writing the material that would become the groundbreaking album from which Walsh took the other half of his title. As they wind in and out, the lines between coincidence and some deeper connective tissue between events become blurry, or at least open to interpretation.

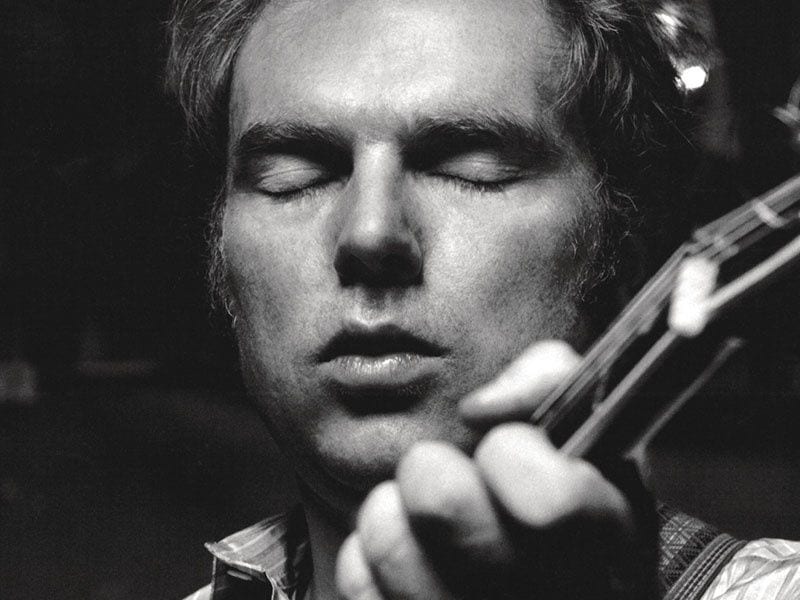

Walsh’s Astral Weeks began as a Boston magazine feature, published in 2015. It’s not obscure knowledge that Morrison spent time living in Boston in the late ’60s, but no one had bothered to ask the question that was central to Walsh’s article; “What was he doing there at all?” The answer, as Walsh discovered, is that he was laying low after the dissolution of his band Them, drinking himself into oblivion, and fighting with producer Bert Berns’s Bang Records. It was a chaotic moment in the singer’s young career. Because Morrison refused interview requests for the article, Walsh constructed him using other people’s memories.

His article, “Astral Sojourn“, drew vivid portraits of the moons circling in the Morrison solar system during that transformative time. They included Peter Wolf, musician John Sheldon, and most poignantly, Janet Rigsbee, who was married to Morrison and is known to his fans as Janet Planet. “I invite you to imagine a world in which your memory of an early, intense, turbulent relationship is constantly triggered by something as ubiquitous and iconic as the song ‘Brown Eyed Girl'” Walsh wrote, in a leap of sympathy for Rigsbee. “Being a muse is a thankless job,” she told him, “and the pay is lousy.”

Walsh closed the article by wondering if part of the reason Morrison has come to obscure the Boston roots of Astral Weeks is because of painful memories associated with his relationship with Rigsbee. The article’s final image is of Morrison, years later and on a tour stop in Boston, driving with Wolf. At Morrison’s insistence, they stop for a moment outside of the apartment he and Rigsbee had shared in Cambridge.

It’s an excellent article and it led to inquiries from Penguin about turning the 5,000-word piece into a book. Walsh remembers getting the initial email while stopped for gas on the way to a performance with his band, Hallelujah the Hills. “I think I just got an important email,” he told his band mate. He leapt at the opportunity, approaching the project with an estimable amount of confidence for a first-time writer. He kept his day job and set his mornings before work and his weekends to researching, chasing down interviews, and writing. “I figured I could do anything for 18 months,” he says.

The initial idea was to keep the focus on the events directly related to Morrison’s work on Astral Weeks, completing the story begun with “Astral Sojourn”. It’s a story with a remarkable number of avenues: record executives buying out contracts with large bags of cash dropped in garages, Morrison’s desire, fueled by a dream, to abandon electric instruments, and his quest to make a masterpiece while simultaneously extracting himself from a business deal overseen by low-level mobsters.

The story turned out to feel incomplete, and Walsh expanded his view to include more of the hectic and unchronicled psychedelic and artistic scene happening around Boston. The result was an intriguing mix. The Velvet Underground played more than a dozen shows in the city in 1968, and the back cover of their White Light / White Heat album was shot outside of The Boston Tea Party nightclub. In January, filmmaker Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies, a documentary on conditions at Boston’s Bridgewater State Hospital, was barred from public screenings. In July, James Brown performed a now legendary concert at the Boston Garden on the evening after the assassination of Martin Luther King that is credited with helping to keep the racially divided city from exploding in violence. Meanwhile, MGM Records was working throughout the year to market a group of local bands under the banner of “The Boston Sound”. “I developed certain rules,” Walsh says. “Every story had to have an anchor in 1968 in Boston. It could go to other cities and drift into other years, but something important had to happen in that timeframe. That helped, and ruled things out, certainly. But there was an abundance of things that met that criteria.”

In particular, Walsh was taken with the story of Mel Lyman and his Fort Hill Community, an East Coast commune that hid themselves in plain sight on the outskirts of Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood. Lyman, a musician turned guru who used psychedelics to manipulate and control the community members, is a complicated and mostly unsympathetic character. “There are many on the record accounts of him being someone’s acid trip guide,” says Walsh. “The rules were literally being invented as this happened. [Timothy] Leary and all those guys made these helpful, beautiful rules about how to properly use these drugs. According to these accounts, Lyman purposefully did not adhere to those and you’d come out of it scared to death of him or following him, I think.”

In 1968, through his battles with the city over publication of the community’s underground newspaper The Avatar, Lyman also became a free-speech warrior (then-Boston University professor Howard Zinn appeared at the trial as a witness for the defense). The story of the community makes up as much of book as does the creation of Astral Weeks. In Walsh’s telling, Lyman and Morrison come to form two poles, both seemingly desperate for notice but refusing to be pinned down. Both could be off-putting if not downright creepy, both used dreams to help guide their decision-making, and both were true believers in the spiritual power of music. “People say that Boston is the main character,” Walsh says. “I wouldn’t put it that way but it’s certainly a huge presence and Van Morrison and Mel Lyman are sort of our tour guides.”

Lyman died in 1978 and Morrison, despite Walsh’s efforts, never agreed to an interview. With the two main characters unavailable for comment, Walsh describes the book as becoming almost like a ghost story. For all of the book’s intertwining storylines, Morrison and Lyman never meet in-person. “At a certain point I came to think of that as beautiful,” says Walsh. “The stories dance around each other. They’re both searching for spirituality through music. They’re both on some imprint of Warner Brothers. They’re both bothering the shit out of Mo Ostin at Warners. When the story starts, Lyman is kind of notorious in Boston and Van is a stranger here. Then where the story ends up is completely opposite, Mel is gone and forgotten and Morrison is one of the most famous singers in the world. It’s such an arc, so there was a lot to play with there.”

He opens the book with the incredible story of Lyman, at the time a banjo and harmonica player performing with the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, climbing onto the unlit stage at the close of the 1965 Newport Folk Festival to perform an unscheduled rendition of “Rock of Ages” on harmonica. “I wanted to save the world with music,” Lyman later told a reporter. The 1965 Festival is best known for Bob Dylan’s brief, apocalyptic, “goes electric” performance. Walsh’s casting of the evening’s little known coda as the place to start his story is an unconventional choice. It reflects his view that what happened leading up to, or immediately after, the events in the true-life stories we have come to know, is often just as interesting.

Walsh’s interest in what’s happening just at the edge of the frame extends to his characters, as well. Though some famous names appear in the book, like Congressman Barney Frank and the Velvet Underground’s Lou Reed, it’s often the characters around them who are the most tenderly detailed. Lisa Bieberman, an associate of Leary’s who established a directory for psychedelic drug users in need of assistance, is remembered by a friend as “the ultimate responsible entheogen user.” Walsh shows a keen sympathy for Tom Kielbania and John Payne, Boston musicians who played with Morrison throughout the writing of Astral Weeks but were mostly replaced by ringers during the recording session. He’s able to track down a bootleg, long assumed to be lost, of Kielbania and Payne playing with Morrison at the Boston club The Catacombs. When he plays it for them, Kielbania proudly tells him, “This is how Astral Weeks started.”

Walsh chased down interviews with over 100 of the people who formed the Boston scene in the late ’60s, including members of the Fort Hill Community, some of whom are still living as a commune in Boston, academics, television personalities, filmmakers, and local musicians. In Walsh’s telling, 1968 comes to feel like a magical year and Boston like a magical city, where it was possible to drive the Velvet Underground around town in your dad’s car, like a teenage Jonathan Richman did. Or to send your screenplay to Alfred Hitchcock and get a call from his assistant, like Alan Trustman did. Or to be discovered at a bus stop by a crew scouting actors for Michelangelo Antonioni and suddenly find yourself starring in Zabriskie Point and on the cover of Rolling Stone, like Mark Frechette.

Walsh uncovers one story after another of people desperately seeking enlightenment here, oblivion there. Drugs, music, astrology, religion; the characters in his Astral Weeks insist on pushing them all to the limit in the hopes of getting beyond this world and into the astral plane. With that much loose drug use and dimension-bending going on, things were bound to first get weird and then get dark. After his sudden fame burned out, Frechette died at the age of 27 while in prison for an armed robbery he committed with a member of the Fort Hill community. Guitarist Rick Philip, a local musician who played with Morrison, was murdered in 1969 by his roommate.

Walsh keeps a mostly even hand in chronicling these events, staying to the side as the stories play out. “As soon as I talk to someone or learn their story, some part of me empathizes with it,” he says. “I try not to be judgmental, both in life and in the book. Everyone’s doing good things and bad things, some more than others. I felt it was my job just to try and paint a picture and leave my own opinions out, for the most part.”

Before beginning work on Astral Weeks, Walsh wrote for Stereogum, The Boston Phoenix, and Vice. In many of these early articles, he seems pleasantly transfixed with our social networking age and the possibilities afforded us to role-play, to live through avatars, or to shift identities online from day to day or from message board to message board. You can feel the nagging questions he was running over in his head in these pieces; about authenticity, and about the possibilities for transcendence and transformation, or at least a brief escape, in the everyday things we often take for granted.

Much of his writing dealt with how new avenues for accessing music, particularly downloading and streaming, was changing our relationship to songs and albums. He seemed to take it all with a pleasant detachment and a skeptical eye toward the companies that were slowly coming to dominate the digital space. “When I’m writing pieces about modern day technology, I’m writing those because I really believe music is magic and special and worth protecting. It’s just different technology but it’s sort of the same story.”

In a 2014 article, “Danvers dude makes $23k musically spamming on Spotify” (BDC Wire) he wrote about a man in Danvers, Massachusetts who was uploading thousands of homemade songs with gag titles to Spotify and was managing to eke out a living from curious or confused listeners who stumbled upon them when searching for other songs. In a 2012 article, “The Overdub Tampering Committee” (Medium, originally published in The Phoenix 15 Feb 2012), he wrote about his own work as part of the Overdub Tampering Committee, a group who claimed to have downloaded versions of popular songs that had been leaked on the Internet and covertly uploaded new versions to file-sharing sites with subtly added overdubs. This announcement caused some minor rustling among journalists and music fans. After having had their fill of death threats and hate mail, and after losing the password to the Committee’s email account, the hoax was shut down. “Music is alive, not dead and lying in a digital heap at the bottom of your hard drive,” Walsh wrote in what would be the Committee’s final statement, “and this is just another way of realizing that. Make it, hear it, feel it, tamper with it.”

Though his choice to set his debut book in 1968 may feel strange coming from a writer who has dealt so much with our current times, Walsh is clearly still concerned with many of the same themes. As his story develops, with its musicians hoping to invest their music with spiritual heft and with so many other characters trying to blow through life’s traditionally accepted boundaries with drugs, or with film editing techniques, or with art, Boston in 1968 comes to feel like a setting that was custom-made for his debut novel. “I read a lot of history and am interested, but I’ve never done anything like this. When I finished, the re-entry was a little rough. I felt like I had done some kind of time travel because it was my life for two years, plus. And so many times, something would pop up and I would email my editor and say, ‘I feel like we’re in a loop here.'”