In 2023, writer, musician, and comedian Aug Stone saw his self-published novel, The Ballad of Buttery Cake Ass, included among Vulter’s Best and Funniest Comedy Books of 2023, alongside such high-profile names as Keegan-Michael Key, Leslie Jones, and Scott Aukerman. A broken fire hydrant of jokes, puns, and references, the buddy story follows two music obsessives as they track down a hard-to-find album by the titular Buttery Cake Ass. The story reveals the absurdity at the heart of pop culture mythmaking and conspiracy-spinning as heard in his stream-of-consciousness podcast host, Young Southpaw.

Now, in Sporting Moustaches, his first collection of short stories with Sagging Meniscus Press, he weaves the same web with facial hair. Writer, broadcaster, and beard-wearer Reggie Chamberlain-King asks…Why?

I grew my beard while convalescing after minor surgery in 2006. For a moment, I thought I could look like Dante Gabriel Rossetti forever. 18 years later, I have less hair but just as much beard. Why do you think men are so attached to their facial hair? Do you have any at the moment? Who are your hairy influences?

Well, we are literally attached to facial hair. I’m not quite sure, but maybe it is as biological as that. When I did have a full beard in 2014/2015, I was pleasantly surprised to have women make a point of telling me how attractive it was. My niece, who was five at the time, however, hated it. I was at my sister’s house having dinner one night, and my niece reached across the table, grabbed my face, and yelled into it, “You are not handsome!”

I don’t currently have any facial hair. I’ve never been hirsute, and my early attempts to grow beards were more like noontime shadows, well before 5 o’clock. But I’ve always loved the look of preposterous facial hair, which seemed to signify qualities beyond the visible. I remember being four or five years old and wanting to be a wizard. And, of course, the beard, at least to a five-year-old, is an essential component of the occupation.

I’ve never been asked ‘Who are your hairy influences?’ before, but I’m so glad you did, as it sparked a memory of quite a major hairy-faced man. Within my parents’ larger social circle was a gentleman named Taft who had a magnificent handlebar moustache. I only ever met him once, but it was a historic occasion.

I was 18 and on my way to my first ever hardcore show – Shelter and 108 at The Tune Inn in New Haven, Connecticut – and super excited about it. But first, I had to put in an appearance at a party held by those family friends. As I was leaving, anxious to be on my way, Taft emerged out of the shadows of the driveway and called me over to him. He was quite inebriated and had the air of needing to impart something very important, although he didn’t exactly know what.

So, he just looked at me and, after a moment, said, “Just remember, wherever you go…there you are,” and took his leave, back to the party. I had never heard this expression before and was very amused that he needed to interrupt my departure to tell me this. A similar situation happened with my sister some years later. Taft called her over at a party to bestow the very sage advice, “Never pet a dog that’s on fire.”

On one hand, facial hair is the ultimate sign of masculinity and virility. But it is also a regular source of ridicule, whether it is derision of the hipster or mockery of adolescent bumfluff. You don’t need to dig very far to find humour in soup strainers and food catchers, do you? But, writing about so many moustaches, how do you come up with different ways to describe them?

That’s the thing, I don’t like having the jokes be obvious. Readers can get that elsewhere. Sure, I’ll include them, because I like to have as many jokes as possible and over a wide range, but there’s got to be more to it. And to have the focal point of each story be facial hair, well, it had to go beyond that.

The baseball story, for example, deals with the idea of facial hair as a good luck charm. But I set it in Cleveland, Ohio, so I could also talk about sports curses – that city has a very famous one – and offensive team names. The main point of the stories in Sporting Mustaches is fun, so there are also quite a few references to Bela Lugosi and KISS. So, it was more about coming up with ways to use a moustache or beard in the story than ways to describe them.

I was frustrated early on that there aren’t a lot of words for facial hair, and inventing more myself proved problematic because it seemed like I was trying too hard, and my efforts really stuck out from the page – and not in a good way. Martin Amis passed away right before I sent in the final edits and I went over the text rigorously for about a month and a half. After Amis died, I was listening to a lot of podcasts about him, and one pointed out a review of his – I forget for which author – he wrote something about having to read “one man’s struggle with a thesaurus”. That hit home. I didn’t want my writing to come across like that, so I nixed some rather far-fetched versions of “lip locks”.

There are many facial hair styles with their own names and implications. It’s not a monoculture – it’s rich with variation and division. In your chess story, “Black and White and Red All Over”, for example, the moustachioed junior, Usy, is set in opposition to his Uncle Ilya. Facial hair is pretty competitive in itself.

That came from a real-life story I love: the accusations of black magic and psychic warfare during the 1978 World Chess Championship. In thinking up ways I could use facial hair in sport, or “competition”, in this case, I was very pleased when I hit upon a chess player who could move the pieces with their moustache locks. It comes from a traumatic incident in the player’s youth when learning the game, he picks up a pawn, decides the better of it, and puts it down to move another piece. His uncle, who is teaching him, is so furious at his lack of respect for the rules he throws the chessboard into the fire. Little Usy then sets about growing a moustache to get around the rule that once you touch a piece with your hand, you must move it.

When I was growing up – especially playing chess with older kids – they would get mad that someone younger than them was winning. They could be such jerks, real sticklers for the rules as soon as they started to lose. They’d keep an overly vigilant eye on my hands to make sure not a single skin molecule came in contact with my pieces, but they were secretly dying to call me on it.

This collection of short stories is specifically about moustache-wearers in sport, calling to mind dandiacal Victorian sportsmen like W.G. Grace and W.E. Clegg. Do you think modern sport is missing that gentility?

Modern sport is definitely missing that gentility. The tattoo seems to have taken the place of facial hair. But I see no way for such to exist in modern games. Though wouldn’t it be fantastic if someone started up a Dandy League?

Do you follow sports yourself? Or is it all about the facial hair for you?

I follow soccer, and particularly women’s soccer. (I do call it “football” but I figure since I’m American, that might be confusing). I have yet to choose a men’s team, but I support Chelsea Women’s, they have all my favourite Swedes, like Johanna Rytting Kaneryd; she’s like lightning. I bought her Swedish National Team jersey as an Xmas present for myself this year. There’s also Zećira Mušović – she’s a fantastic keeper, 11 saves against the US in the World Cup, and Nathalie Björn, whose sense of joy I love. When she surprise-hugged Mušović during the last Bronze Medal game, it was one of my favourite moments in all of sport. In the US, I’ve traditionally been a Portland Thorns fan, though Trinity Rodman is my favourite US player. She is just amazing to watch.

For the stories, however, it really is just about the facial hair. Once I had the pun “Sporting Moustches”, it was, “alright, what can I do with this?” The ideas kept flowing. I wanted to include a soccer story, but I couldn’t find a way into one that would be much different from the other team sports that I had already written. Maybe one day, it will come to me. I did start work on a Yo-Yo – where the Yo-Yo moves along an enormous moustache.

Once you bring Yo-Yos into the mix I have to ask if sport as a subject is inherently funny. There are the baseball stories of Ring Lardner, Nick Hornby’s 1992 book Fever Pitch, and of course, there’s the Fantasy Football League. I know you’re a fan of the hirsute, JP Donleavy, whose 1984 book, De Alfonce Tennis: The Superlative Game of Eccentric Champions: Its History, Accoutrements, Rules, Conduct, and Regimen must surely have been an influence.

That’s a good question. Perhaps I have some deep-rooted angst towards all those coaches who took the fun out of sports when I was growing up, and Sporting Moustaches is an attempt to swing the balance back. I loved playing most sports when I was growing up. I was always way into music, too, but my record-collecting obsession became all-encompassing when I hit about 14.

Still, I remember clear as day, attending a basketball summer camp for a week and one of the coaches just being so angry. Like from the minute one. He was barking orders at us. I don’t learn that way. I learn through enthusiasm, which I believe is a much healthier way to learn things than to be shamed and yelled at and have your joy taken from you. So maybe one of the impetuses of Sporting Moustaches was a reaction against that poor man who was always consumed by anger and couldn’t find any happiness in playing the game.

I am embarrassed to admit this to you because a) I know you’re a big fan of De Alfonce Tennis, and b) you know how much I love Donleavy – along with Thomas Pynchon, my favorite writer. We have had many a conversation about Donleavy over the years but I have never read De Alfonce Tennis. That and A Singular Country are both sitting on my shelf, waiting. I’ve read all the others, most of them multiple times. Schultz and its sequel, Are You Listening Rabbi Löw? I’ve read four times, which is a lot for me, and I’ve bought Schultz 25 times. Whenever I see a copy it I buy it and pass it along for someone else to enjoy.

We have talked a lot over the years about books and music, the weird, and synchronicities, since we crossed paths on Livejournal, circa 2005 – the year of my beard. One such synchronicity relates to the illustrations. You worked with beardedex-dandy Allen Crawford, who I crossed paths with on the same platform. But did you know Allen at the time? How did you come together and what was it like working with him?

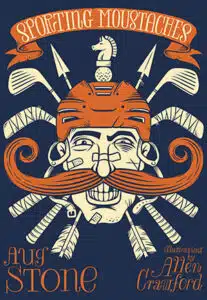

That is an excellent synchronicity! Allen is a complete joy to work with. He’s incredibly talented and also very quick. He came up with the brilliant cover illustration in, like, a day. Initially, I thought I wanted the art to go with each story to be Edward Gorey-esque, but then it hit me – and I was very pleased with the extra pun, despite it only being used in talking about the art – that what I really wanted on the cover of Sporting Moustaches was the style of Aubrey Beardsley. I wrote to Allen it should be “without the eroticism as that might get confusing.” Allen responded that Beardsley was a better fit for him stylistically and that “We’ll keep the engorged satyrs to a minimum.”

I also became aware of Allen through Livejournal and around that same time. Momus mentioned him often, so I checked out his work. A few years ago, I asked him to design the cover sleeve for my Young Southpaw Ouroboros single, and he did an excellent job. When I decided it would be nice to have the Sporting Moustaches stories illustrated, Allen was the first person I thought of, and awesomely, he was up for it.

Your previous book, The Ballad of Buttery Cake Ass, explores the absurd obsessive drive of male music fans. Perhaps especially your own obsessions. In Sporting Moustaches, too, we see sportsmen driven to hilarious lengths, mostly by their love of sport and frequently by their love of women. Why do you think fans and men take things too far?

Once I like something, I want to know everything about it and everything it is connected to. Only recently I’ve come to recognize this as greed. Or maybe hedonism is more accurate; I want more of the pleasure I experienced through those works. I hope it’s not that bad because I also love to share these things with people. That’s why I write about music, books, and comics, mostly for The Quietus and The Comics Journal these days.

I don’t consider myself so much a journalist as an enthusiast. It’s always been, “You gotta hear this!” I fondly remember being 17 years old and finally getting my hands on Public Image Ltd’s Second Edition (as Metal Box was known here in the States). I brought it home, listened to it, was completely floored, and immediately drove to my friend Jon’s house because I felt he needed to experience what I had. But man, starting with those ten-plus minutes of “Albatross” is tough, haha.

Speaking of the greed realization, I’ve come to see this about my creativity, too. I have so many ideas and find it difficult to pick just one and work on it until completion. But you have to or else nothing gets done. Other people understand this, but it’s incredibly difficult for someone with such a fiery personality as myself.

Sporting Moustaches is certainly full of ideas, but you have themes. For example, the obsessives and eccentrics of these stories generally come out on top or, at least, unscathed: the Wizard of Wycombe, a whizz at badminton, describes the longed-for letter W with his shuttlecock; the three-faced race, first run by two contemptuous dandies, becomes a community tradition. Ultimately, you’re on the side of the weirdo. Do you consider yourself a bit of a weirdo?

Without a doubt. I think I’ve always considered myself and been considered by others a weirdo. The only reason I consider myself a weirdo is because others have stressed how strange my way of looking at the world is. To me, it seems perfectly natural.

I remember being six or so, and my best friend’s family was over for a pizza party, and I referred to the cheese of the pizza as “the skin”. I thought this was funny; the cheese is the outer layer of the pizza, and underneath that, there’s red sauce like blood… but my friend looked at me as if I’d just arrived from Saturn.

Ever since then, I’ve known I was an oddball, though it took a long time to fully grasp just how much. I’ve always been interested in things outside the norm, too. I had older cousins who lived in Australia for a while when I was very young, and they introduced me to Asterix and Tintin comics, which were pretty much unheard of in my part of the States at the time (the early ’80s). I dressed up as Getafix for Halloween when I was eight. No one knew who I was supposed to be or even knew what a druid was. So, I settled for people thinking I was dressed as a “wizard”, tying into my youthful ambitions.

I was very lucky to find in my hometown others who loved music and comedy as much as I did. Still, the thing about being weirdos is you feel the ostracization from society as a whole, even if you’re in a group. Of course, most interesting stuff comes from the fringes before getting diluted and accepted into the mainstream. But that feeling of belonging to a group is nice, and not having to deal with the hassle of derision anymore because normies are no longer affronted by the bands you listen to or what you find funny, that’s a plus. So having the dandies in “An Early History of the Three-Faced Race” story come felt nice to write. Not that they’re not problematic individuals themselves, but hey…

You couldn’t leave music alone, even in a book about sport and facial hair. The unearthed Excalibur-like magical golf instrument is called “The Cavern Club“. There are hidden musical references everywhere: brothers called Ray and Dave, whose father is called Arthur; Alanis Morrisette, Lee Geddes, and Randy Osbourne.

Music is indeed my obsession. I try never to miss an opportunity for a joke, and it’s usually music-related, like the baseball story set in a Hungarian suburb of Cleveland. The team are dealing with their name being changed from the Magyars to the Goulash. I once knew a Hungarian guy with the last name of Kis so why not give the Coach the same surname so I can give him dialogue of KISS lyrics? I will never miss an opportunity to talk about the effect David Lee Roth leaving Van Halen in 1985 had on a character’s psyche, such as the case of a team in the Three-Faced Race story wearing black armbands to commemorate the event.

Sporting Moustache begins with an ice-hockey player recognising an occurrence of synchronicity. Another character tries to combat the bad luck he’s sure to face after damaging an illustration of a mirror reflected in a real mirror. Other characters perceive good omens in letters and numbers. This hyperconnectivity of thinking is central to your humour in the rambling Young Southpaw routines. Is this really how you think?

It is. People don’t believe me when I say how much my brain functions like Southpaw. I see connections everywhere, and my brain seems to have at least four different thought pathways to take at any given time, which also resonate between themselves. I’m surprised I get anything done at all. There can be real joy in this, but I also recognize that having this be my default way of thinking has negatively impacted more practical areas of my life. I’ve been reading about Neuroplasticity and trying to get an appointment with a neurologist to figure out what’s happening. I wouldn’t want to necessarily change my creative brain, but it does make it difficult to live in the so-called real world.

Something is often revealed behind that thinking, like in a Thomas Pynchon novel. Do you think you’re getting at something deeper when you point out these connections? Or is it about the absurdity of existence, like Robert Anton Wilson‘s books?

Good question. I love both of those writers. There’s that great quote from Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow – “Like other sorts of paranoia, it is nothing less than the onset, the leading edge, of the discovery that everything is connected, everything in the Creation…” I posted this on the home page of youngsouthpaw.com, with Southpaw following up with “Hold my beer.”

The important point is resonance, which produces overtones, causing you to sense things you might not have otherwise. Deeper meanings could be revealed, but it could also just be for the joy of wordplay. Given the current state of the world, if you can find joy in something these days, that is meaningful enough. But to paraphrase Freud, sometimes Sigur Rós is just Sigur Rós.

Wordplay is a compulsion for you. But how do you decide when the wordplay is right? In “The Ache in Moustache” the barber shop is called To Shave and Hold, which is self-conscious in how it doesn’t work phonetically, but only for the eye.

Yes, you’d miss that one with the audiobook. Pynchon has one like that in Bleeding Edge, talking about Scooby Goes Latin and “those Medellin kids”. The narrator pronounces the Columbian city name in the audiobook with the correct double-L-as-Y sound, and the pun is lost. Perhaps too many purely visual puns could be a bit off-putting. My favourite joke I’ve made up is like that, too: “There is no ‘I’ in ‘Optometry’.”

But yes, to answer your question, wordplay is definitely a compulsion for me. It was inevitable, growing up around my dad, to whom Sporting Moustache is dedicated. I get my sense of humor from him, which comes from a huge love of wordplay. I get my love of music from my mom, so everything comes together in my work like that.

You’ve come into this interview having recently suffered a concussion. Do you think you’ll stand by these answers when you come ’round?

Ha! I hope so. It’s been a very strange time. I don’t recommend getting yourself a head injury. Being off work with anything else, at least I’d be able to write all day, but I’ve had to severely limit my screen time to let my brain heal. My short-term memory has been affected, and that’s been a bit scary, not being able to remember stuff you just thought of. But maybe how my brain sees connections has been beneficial because I can usually find my way back to it.

The knock to the head might’ve unleashed some memories buried for a while. It was wonderful to think of those encounters with Taft again. So, in parting, I’ll reiterate his words of wisdom: “Never pet a dog that’s on fire.”