The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

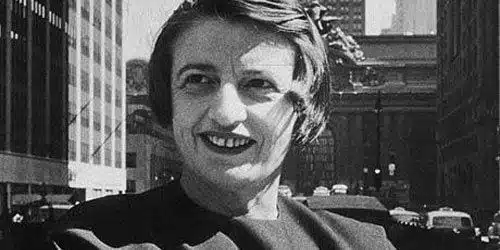

Born in St. Petersburg in 1905, Alyssa Zinovievna Rosenbaum, later Ayn Rand, belonged to a family of medical Jews: pharmacists, dentists, and doctors. But Judaism in turn-of-the-century Russia was a great misfortune, one author Anne C. Heller builds on in her excellent biography, Ayn Rand and the World She Made.

Heller, amazingly, didn’t come to Rand’s work until her 40s while working at a business magazine. Suze Orman, of all people, introduced Heller to Rand’s work. Perhaps it was Heller’s late discovery and the Ayn Rand Institute’s refusal to allow her into the archives that allowed her to write such a vivid yet objective portrait of this gifted, brilliant, ultimately monstrous author. Heller is to be commended for deftly sidestepping her difficult subject.

In her preface, Heller notes, “Because most readers encounter her (Rand) in their formative years, she has had a potent influence on three generations of Americans.” I was 15 when a friend lent me The Fountainhead (he let me keep the book, a Signet paperback costing $3.50). I liked the novel but was mystified by Dominique and Roark’s relationship.

Though impressed by Anthem and We the Living, Atlas Shrugged knocked me sideways. Like millions of female readers, I wanted to be Dagny Taggart, with her slanted hat brim, slender body, and long legs, terminating in painless high heels. Dagny Taggart was the antithesis of both her creator and this admirer, both of us hopelessly brown-haired, short, stumpy Russian Jews.

Not for elegant Dagny Taggart, the indignity of menstrual cramps or shreds of food in the teeth. Hell, the woman barely ate. Instead, she expertly ran the Taggart Transcontinental Railroad, her energy boundless, her emotional indifference lending her a Terminator-like indestructibility. For her efforts, Taggart was rewarded with a series of brilliant, handsome lovers whose lovemaking, if a bit rough, offered exactly the domination this otherwise steely woman – and her creator – secretly craved. Her creator, however, was not so fortunate.

Ayn Rand’s Objectivist philosophy, which still carries weight today amongst serious economists – Allan Greenspan, until the recent financial crash, was a confidante and lifelong devotee of Rand’s brand of free-market capitalism – never entirely jibed for me. I’m no economist, but I’ve spent 25 years wondering why Atlas Shrugged’s Eddie Willers, loyal and hardworking to the bitter end, was left to wander New York’s darkened streets, his sole offense insufficient brilliance.

An average man, what Rand’s nervous followers later dubbed a “second-hander“, Willers’ dedication, coupled with his average intellect, was insufficient currency for admission into Galt’s Gulch. And what of the truly needy — the ill, the developmentally disabled, children, the elderly? Is giving these people economic support a morally reprehensible act?

Ayn Rand certainly thought so: lesser mortals did not fit her vision, which was simultaneously luminous and stifling. She preached that one could create himself (and her lexicon was definitively slanted toward men), achieving his highest ends via logical thought. Such a notion is certainly intoxicating, if not always realistic. But Rand set out to remake reality as if it were an ill-fitting dress: by sheer will, she tried to fashion a Balenciaga gown from a housedress.

Though ultimately outwardly successful – Ayn Rand’s books remain widely read, appearing regularly atop “best of” and “most important” lists – she was a miserably unhappy person whose cruelty, selfishness, and indifference were breathtaking.

Ayn Rand’s Fundamental Formation

Alyssa Rosenbaum’s fierce intelligence displayed itself early. She was headstrong, read and wrote much, and evinced a lifelong disinterest in physical activity. She often clashed bitterly with her mother, Anna, who left dentistry to pursue a socially mobile lifestyle. Alyssa’s adored father, Zinovy, was a well-to-do pharmacist until Russia’s government began destabilizing. As attacks on Jews became commonplace, many of Zinovy’s relatives fell to pogroms. In St. Petersburg, the Rosenbaum family’s economic fortunes suffered under tottering governmental rule. At one point, 12-year-old Alyssa watched as Zinovy’s pharmacy was looted by Leninist thugs, leaving a searing impression of Communist rule.

Alyssa’s intelligence afforded her entry into a private girl’s school, where she made one friend: the older Olga Nabakov, who had a brother named Vladimir. But as the political regime became increasingly brutal, the Nabakovs fled. Alyssa never saw Olga again. Zinovy lost his job, forcing Anna to take up teaching. Alyssa derided Anna’s efforts, dismissing her mother’s work as consorting with the enemy. That consorting put food on the table.

By age 17, Alyssa had carefully mapped her escape. Anna had relatives in Chicago willing to take Alyssa in, but her antisocial behaviors soon bewildered them. She stayed up all night, heedless of her sleeping relatives, running endless hot baths. She adored the movies so much that a relative in the business contrived to get her free tickets. Then there was her name: instead of the Americanized Alice, she insisted on “Ayn”.

Explanations of her re-naming are legendary; Heller writes that “Ayn” may be variant of Zinovy’s nickname for his daughter: “Ayinotchka” — a Hebrew diminutive for “Ayin”, or “bright eyes”. How she arrived at “Rand” remains unknown, for the myth of naming herself after the typewriter is just that: Rand was not manufacturing models at the time of Alyssa Rosenbaum’s rebirth.

The bright-eyed girl was unimpressed with Chicago and soon moved to Hollywood, set on writing for the movies. Given her stilted English and heavy accent, she was remarkably lucky. Like her name, any number of stories surround how she met Cecil B. DeMille, who hired her to work at DeMille Studios. There she met her husband, Frank O’Connor, who was working as an extra.

Rand was besotted, literally tripping O’Connor to initiate a conversation. Nine months later she ran into him at the public library. They began dating and were soon lovers. Their 50-year marriage was one of the greatest mismatches in history.

Fueled with Amphetamines, Coffee and Chocolates

O’Connor, by all accounts, was an exceptionally beautiful man, gallant, well-mannered, and unfailingly kind. But his intellect was no match for Ayn’s. A quiet, retiring soul, O’Connor deferred to his wife’s intense ambition. A lifetime of repressed wishes and hopes, along with silent acquiescence to Rand’s affair with Nathaniel Branden, had a devastating effect on this gentle man, who ultimately drank himself into dementia and death.

Rand worked hard, fuelling herself with amphetamines, coffee, and chocolates, gradually achieving the literary fame she longed for. It’s difficult to imagine that any of Rand’s books, with their stridently Capitalist themes, violent sex scenes, and overt atheism, would ever reach print today. But over time — between 1932, when she sold her first (unproduced) screenplay, and 1957, when Atlas Shrugged appeared to critical scourging and enormous sales, Rand grew wealthy, famous, and drew a circle of followers — Objectivists — whose fanatical devotion was near cultlike.

The most amazing aspect of Rand, deftly laid out by Heller, was the breach between her thinking and behavior. Rand once described herself thusly: “I think I represent the proper integration of a complete human being”. Yet this integrated being was often poorly groomed, greeting guests clad in stained clothing and torn stockings. More than one acquaintance commented on her lack of hygiene. Yet she possessed an irrational fear of germs, likely a relic from her Russian childhood. But even more startling than her indifferent appearance was her increasingly erratic behavior.

As her fame grew, Rand demanded those close to her adhere entirely to her philosophy. Her life soon took on an alarming pattern: she made new, usually younger friends who were enamored by her charismatic brilliance, only to find themselves excommunicated from her circle, often over minimal offenses. To be a part of Rand’s coterie required an exhausting commitment of self-repression of unseemly emotions, efforts to “cure” homosexuality, which she abhorred, marrying appropriately serious fellow Objectivists. Those who deviated were summoned to Rand’s home, where they were subjected to degrading mock “trials” by Rand and her followers. Fifty years later, in interviews with Heller, many of these people are still horrified, pained, and ashamed.

Rand, meanwhile, exhibited decreasing interest in her biological family, whose fate in the Soviet Union was unknown for decades. She never thanked her Chicago cousins for their efforts or repaid the money lent her as a young immigrant. She was, she claimed, entirely self-made. Letters from her family, found among her papers after her death, repudiate this notion.

Heller’s recitation of Rand’s friendships and fallings out is fascinating yet depressing reading. Rand was fighting for intellectual respect long before women’s rights. Her ruthlessness brings to mind certain contemporaries: Simone de Beauvior, who, though capable of great generosity, was often imperiously dismissive of her lovers, Anaïs Nin, who guiltlessly juggled multiple lovers, including her father and husband, before decamping to California, where she married the younger Rupert Pole, neglecting to divorce Hugh Guiler, or, for that matter, inform him of her decision.

Colette also comes to mind. Though utterly unlike Rand in most ways, she slept with her stepson, made anti-Semitic remarks while married to a Jewish man, and treated her daughter appallingly, expressing horror when the young woman admitted to lesbianism. Evidently her own long affair with Missy slipped her mind.

While these women were up against formidable obstacles as writers, that does not negate their behaviors. And Rand behaved perhaps worst of all when Nathaniel and Barbara Branden entered her life. More than two decades her junior, Nathaniel nonetheless personified the superman Rand longed for: brilliant, handsome, an earthly John Galt — or so she thought. Despite her marriage, despite Nathaniel’s marriage, Rand pulled the younger, besotted man into an affair that would last some 13 years, causing tremendous pain for all parties.

Yet when the affair waned, Rand, nearing 60, refused to see the obvious: that Branden’s marriage to Barbara was over, that he was engaged in a serious relationship with Patrecia Gullison, who would become his second wife. Hours were spent haranguing not only Nathaniel but Barbara, who remained astonishingly loyal to Nathaniel as Rand lashed out irrationally, threatening to destroy Branden’s flourishing career as writer and therapist.

Branden eventually summoned the courage to end the affair with Rand. The scene was a harrowing one. Rand, arguably out of her mind, banished Branden from her life both personally and professionally, vowing to destroy him. She failed. At the end of her life, she reconciled with Barbara, but never again saw Nathaniel.

Her circle shrunk. Only Leonard Peikoff, a young cousin of Nathaniel’s, remained loyal, to his ultimate professional detriment. As Frank slid into dementia, Ayn relied on her secretary, Susan Weiss, housekeeper Eloise, and Peikoff. Eventually even Susan, unable to endure Rand’s outbursts and Frank’s decline, left her position. Frank O’Connor died in 1979 from arteriosclerosis and alcoholism. His famous wife lived three more lonely years, giving the rare speech.

Years earlier, appearing on television with Mike Wallace, who commented that few could meet her standards, she replied, “Unfortunately, very few” (italics Rand’s). At the time, her answer was proud. Later, though, as the Dagny Taggarts and John Galts failed to materialize, Rand fell into the kind of depression many today can empathize with, for very different reasons: Rand realized, too late, that the bright, joyous world of her imagination would never find an equivalent in reality. For a woman possessed of rigorous logic, retreat into fantasy was impossible. The only thing left was loneliness. Were she not so cruel to her fellows, one might — to her horror — pity her.

To Heller’s credit, she brings to life not only Rand but her circle and their milieu, making the book readable if only for its glimpse into a not-so-distant past where serious literature was widely influential, the television new, the railroad a common mode of travel. It’s strangely quaint to read about a world without computers or cell telephones, a world where typists were a must and people wore hats as a matter of course. Even more extraordinary is her rendition of this wildly divided woman, who could create some of our most unique literature yet remain unable to make that most fundamental of connections: unconditional love for another.