Westerns tell the story of America — or more precisely, they tell the story of America from its own perspective. As the national culture evolves, the western follows, along with all its grand theories about independence, freedom, and honor. The first westerns shaped the country’s beliefs and convictions through contrivance and fabrication, repressing generations of wicked violence and exploitation under platitudes about exceptionalism and liberty; revisionist westerns in many ways dismantled the fiction, and answered America’s mythology with the reality of the brutality of the frontier. Over time, the tales Americans told about themselves have dredged out the marrow of American character.

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, the latest film from the Coen Brothers, in an anthological epic about the enormous breadth of American vice, but it’s equally about that kind of storytelling. It has all the western tropes: through its six vignettes, the film portrays pistol duels, bank robberies, public hangings, shootouts, prospectors, stagecoach rides, and the romance of gallant cowboys and virtuous maidens. These disparate elements are unified with an overused but appropriate framing device: each of the stories comes to life out of the pages of a western fiction collection. The result is a movie that engages not only with the ways America sees itself in the 21st century, but also with the fables it has long been captivated by.

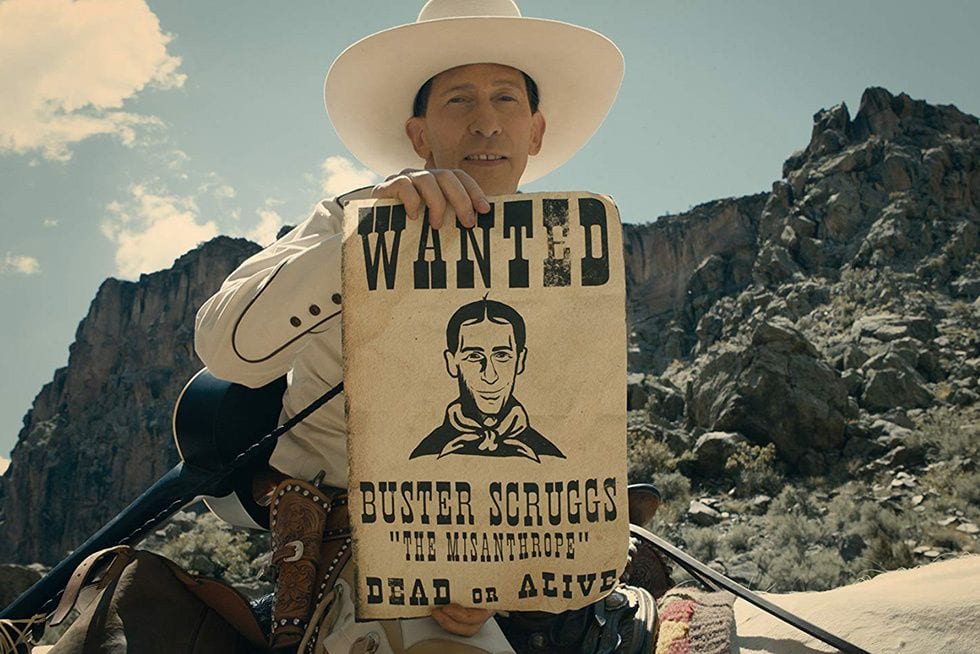

The titular story opens the film with a cartoonish figure of myth: a legendary gunslinger and balladier named Buster Scruggs (Tim Blake Nelson). He’s unveiled as a conventional white-hat cowboy, the standard western good guy, despite being a wanted man. He speaks directly to the audience with cheerful eloquence and a carefree attitude, totes his guitar on horseback, and sings goofy songs in the desert wilderness. He seems harmless. But when he enters a saloon in the middle of nowhere and the gruff patrons don’t take to his dopey demeanor, he shoots everyone present with frosty precision.

The rest of the first story revels in these extremes: Scruggs’ aw-shucks heroics and his preponderance for ultraviolence. But why name the movie after (or even begin with) this relatively short — and, frankly, underwhelming — tale? Buster Scruggs may well be emblematic of America itself: a quietly sharp and calculating killer with the outward affectation of friendliness and diplomacy. It reminds us of the falseness of the gunslinger mythology used then to sell paperbacks and, eventually, tickets to the cinema. The Coens begin the film by dismantling not just the idea of the American hero, but the entire basis of American identity. The allegory of “Buster Scruggs” sets us up for the subversion to come.

The five remaining sections of the movie tell stories of hubris, injustice, and greed, devastating cruelty and breathtaking compassion — though considerably more of the former than the latter. “Near Algodones” follows a bank robber’s (James Franco) path to justice; “Meal Ticket” is a tragic story of a traveling impresario (Liam Neeson) and his companion Harrison (Harry Melling), an actor without arms or legs; “All Gold Canyon” is about a kooky prospector’s (Tom Waits) perilous quest for gold in the pastoral wilderness; “The Gal Who Got Rattled” is the tale of the meeting of an anxious young woman (Zoe Kazan) and an honorable cowboy (Bill Heck) in a caravan to Oregon; the ominous “The Mortal Remains” closes the film with a ghostly stagecoach ride from the perspective of five strangers (Tyne Daly, Brendan Gleeson, Saul Rubinek, Jonjo O’Neill, Chelcie Ross). The massive and talented cast, unlike that of the Coens’ previous film, the star-studded showbiz comedy Hail, Caesar!, goes completely unwasted. Even among brilliant performances from section leads like Waits, Kazan, Nelson, and Melling, bit roles such as Stephen Root as an eccentric bank teller and Rubinek as a provocative Frenchman are incredible scene-stealers.

Each of the sections deal with distinctly American themes, and they’re themes the Coens have explored from nearly every angle previously. Indeed, parts of Buster Scruggs will bring to mind Coen classics like Fargo, O Brother Where Art Thou?, and Inside Llewyn Davis. Of course, by taking on western conventions with familiar motifs, the Coens risk treading on stale ground. Still, there’s something altogether new about having these revisionist western ideas filtered through the Coens’ rich sense of character, black comedy, and their penetrating awareness of humanity’s fatal imperfections. Perhaps now, when so many of the calamities hidden in the very soil of America have been freshly exposed to air, such insights can take on added meaning.

As one would expect of the Coens, the six sections of the movie diverge wildly in mood, style, and ambition. Tonally, the pieces range from the absurd (“The Ballad of Buster Scruggs”) and ironic (“Near Algodones”) to the heartbreaking (“The Gal Who Got Rattled”) and haunting (“The Mortal Remains”). Shot by Inside Llewyn Davis‘s Bruno Delbonnel, the movie’s cinematography, special effects, and color grading also shift to match the particulars of each story: the lush prairie of “All Gold Canyon” is emboldened with oversaturated colors, while the stark blue lighting of “The Mortal Remains” deepens its otherworldly feel, and the synthetic backdrops of “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs” accentuate its themes of artificiality and legend-creation.

The screenplay is meticulously conceived for the most part — authentic when it needs to be, engaging and unpredictable when it doesn’t — but each short also has its own approach to dialogue: some characters, like Scruggs, are irritatingly loquacious, while others, like the performer Harrison, are deafening in their silence. Structurally, the first two stories end abruptly, largely for comedic effect, while “All Gold Canyon” and “The Gal Who Got Rattled” are drawn out to support their more dramatic heft (incidentally, they’re also my favorite of the six). To some, the erratic variations in style across the movie may mean many of the stories never land for them, but fans of the Coens should be braced for such violent deviations from the start. At the very least, the film has something for every kind of Coen Brothers fan.

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is a revisionist western for the era of national cynicism and acute polarization. There’s a reason the film ends with “The Mortal Remains”, a more-or-less plotless exercise that brings five unique characters — most of them immigrants — into forced conversation and heated debate about religion, decorum, and death, all the while en route to the same unknown destination. Near the end of the short, the English bounty hunter (O’Neill) opens up about his talents for storytelling to lure targets to their death. “People can’t get enough of them,” he says. “They connect the stories to themselves I suppose, and we all love hearing about ourselves.”

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, like most in its genre, is about the careless brutality of the West and of America, but more importantly, it’s about how a national identity founded on that inhumanity is doomed. It’s a movie that asks Americans not only to be conscious of their own mythology, but to recognize the impact of the stories they tell on the shape of the world and themselves. For all its flaws, it’s the story of America as it is now, because of what it was then.

- 'True Grit' Brings Out the Best in the Coen Brothers - PopMatters

- Rescripting the Western in 'No Country for Old Men' - PopMatters

- No Country for Broken Men in Joseph Scapellato's 'Big Lonesome ...

- Okay, Real Good, Then: The Coen Brothers as Leading Men ...

- 'Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter' Finds Riches in the Coen Brothers ...

- It's Going to Be Hard for 'Fargo' to Seem Like Anything More than ...

- Twin Talents: The 10 Best Films by the Coen Brothers - PopMatters

- What 'O Brother, Where Art Thou?' Gets Right (and Wrong) - PopMatters