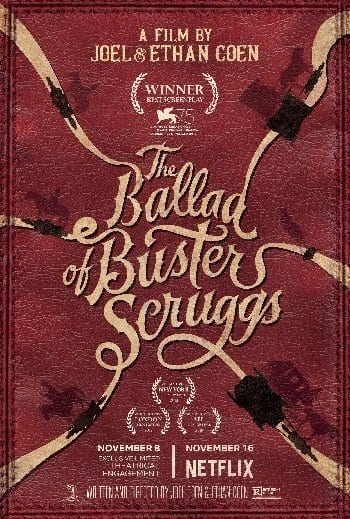

The short film, outside of the anthology, has never fully achieved the level of regard or commercial-ability held by its literary relation, the short story. For comparison, one only need consider Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper (1892), and Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery (1948), both published as individual stories, although the latter also comprises a collection of Jackson’s short literature. Yet the irony in cinema is the popularity of the anthology, most notably in the horror genre, although outlier examples include: Robert Altman’s Short Cuts (1993), an adaptation of stories by Raymond Carver, Damián Szifron’s dark comedy Wild Tales (2014), and now Joel and Ethan Coen’s six part western anthology, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018).

Not dissimilar to a music album, which is judged as the sum of its parts, so too must the film anthology be critiqued in this same way. Unlike the evasiveness of the consistency of the whole sum of V/H/S (2012-14), Southbound (2015), Holidays (2016) and XX (2017), Wild Tales (2014) and now The Ballad of Buster Scruggs have mastered that which seemingly eludes so many filmmakers. Or at least the pattern suggests within the horror genre. Yet in spite of the strength of presence of the individual stories that comprise The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, the short film as the poor relation to its literary counterpart has not been diminished.

The best anthologies exemplify the merit of the short form, evoking a pleasure through continuous movement, as one story ends and another begins. While The Ballad of Buster Scruggs evokes this through the order of the stories and their characters complementing one another, the Coen Brothers have offered viewers an experience that in equal measure evokes a sadness beyond it characters’ fates. Their second foray into the western genre following True Grit (2010) represents a mourning for the short form’s dependency on the storyteller in cinema, which unlike the literary short story, is equal to the author, if not the latter humbly mastering its intricacies. As much as it pains me to write these words, cinema is the lesser storytelling form. This sad aura of truth that surrounds The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is, however, fitting for a film of dramatic and humorous stories that are defined for the most part by a humorous and not so humorous series of tragedies.

This latest offering from the Coen Brothers will not convert those unconvinced or won over by their previous films, the colourful yellow light of the American west offering no road to Damascus-like transformation of belief or opinion. Even for fans of the directors, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs has the air of a complimentary film, perfectly pleasant and with that Coenesque charm. Yet it has the feel of a metaphorical stroll in the park, as opposed to weight of impression their Cormac McCarthy adaptation, No Country for Old Men (2007) made for example, with its subversion of narrative expectations, and deviously playful nature.

These six stories show the cruel fates of characters against the landscape of the mythic American West. From the opening title story that shows the fallacy of ego, the film opens with playful humour. Buster Scrugg’s awareness of his reputation is matched by the story’s own self-awareness, humorously playing around with the colour coding genre conventions, in itself an exaggerated echo of the subversion of John Ford’s hero Henry Fonda by Sergio Leone in Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). The humour is matched by a visual playfulness, and yet while this larger than life character dominates the screen and the film’s title, by the time the end credits roll he has faded away, overshadowed by two stories in particular: “Near Algodones”, starring James Franco as an outlaw caught up in an inescapable fate, and “The Girl Who Got Rattled”, starring Zoe Kazan as a young unmarried woman on the trail to Oregon.

Amidst the order of the stories and their characters complementing one another, what drives the film is an emotional simplicity. The movement from one story to the next, of a beginning and an end, is effectively set-up at the close of the opening episode, with the fate of Scruggs almost acting as an overture for what is to follow — fleeting moments as the page turns, if you will, and a new story begins. The way the fates of characters are juxtaposed with the process of life continuing strikes an emotional chord that creates a haunting experience that is powerfully struck in these installments. This perhaps taps into our mortal fear of death, and innate fear of life continuing without us. Yet beneath such primitive feelings, the simplicity of life, both halting and continuing, is effectively captured in the lead up to the final story, where the Coen’s allow for a little existential questioning with a humorous and dark conclusion. It’s not, however, that final image that makes a lasting impression; rather it’s the emotional chords struck by a trait of the Coen’s – characters that seduce us and draw us into the world of their story.

Ray Bradbury spoke of the short story having “its own intensity, its own life, its own reason for being” and this collection conforms to part, or all of Bradbury’s prescribed criteria. While the final story in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, “The Mortal Remains”, presents a theme that threads the short films together, each is still able to assert “its own reason for being”. But perhaps the success of these six stories is a literary dimension, or rather unlike other anthologies that rely on the filmic form, the Coen’s have told for the most part stories that could have been literary shorts.