Some things you can’t unsee. They become afterimages, a kind of mental scar marring your visual memory. They haunt you. The sixth page of Fabien Vehlmann and Kerascoët‘s Beautiful Darkness is currently haunting me: a child’s corpse lying on a forest floor. I’m a parent and so especially susceptible to the horror of the image, but it’s more than that. Poe misogynistically claims there’s no subject more poetic than the death of a beautiful woman (“The Philosophy of Composition“), but since his wife was 13 when he married her, “girl” would be the more accurate term.

The girl of Beautiful Darkness looks to be about ten-years-old. Her hair is splayed around her head, and although her eyes are closed and her body could be relaxed in sleep, she is unquestionably dead. Over the course of the next few dozen pages, her body rots to bones.

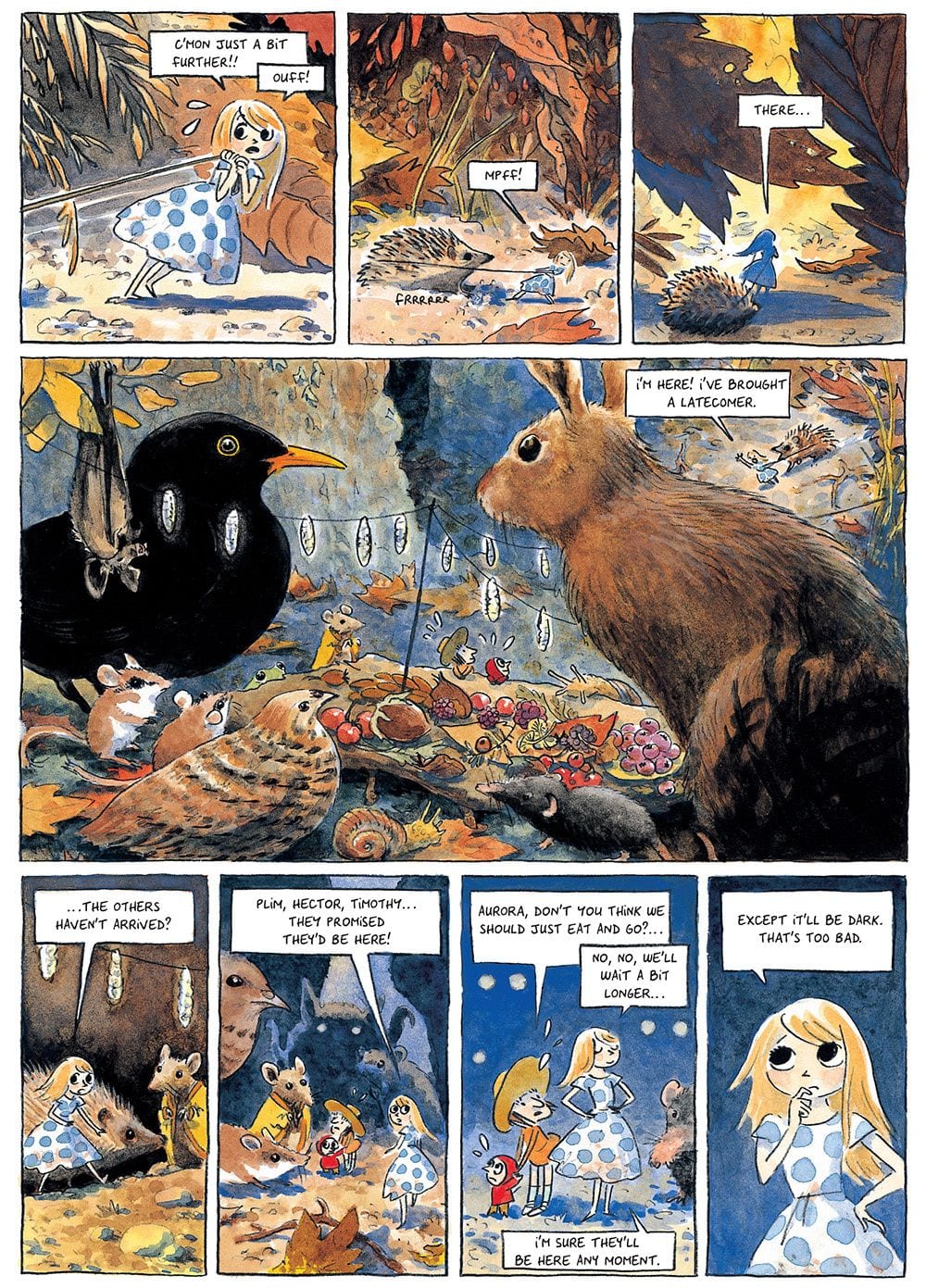

Despite the mysteries and plot questions evoked by the opening image—Who is she? How did she die? Is there a killer? When will someone discover her body?—the novel ignores them all. Aurora (we learn her name from the notebook strewn beside her) is not the focus of this graphic novel—or at least not this version of her. The authors focus instead on another Aurora, a lovely cartoon creature who lives in a fairy tale world of tea parties and princes. Or she does until the borderless panels of her first page darken into rigid gutters as a surging Blob-like goo forces her and her cartoon companions to flee the child’s dead body and emerge into the most horrifying world of them all: our own.

It’s rare to find such a horrifically eloquent concept executed so perfectly. Beautiful Darkness was originally published in France in 2014 as Jolies Ténèbres. Though Fabien Vehlmann receives solo writing credit on the cover, the title page credits Marie Pommepuy for original idea and co-story, translated in the new Drawn & Quarterly edition by Helge Dascher. Kerascoët is the lone artist, and the juxtaposition of his two styles is the novel’s most pervasive and powerful technique. The characters vary in proportions, but all fit the exaggerated and simplified norms of cartooning, specifically children’s books cartooning. The setting, however, including the vegetation and the animals and the hill-like shapes of the corpse they fled from, is naturalistic with finely defined contours and painterly depth. The visual contradiction defines the graphic novel’s core: these things do not belong together.

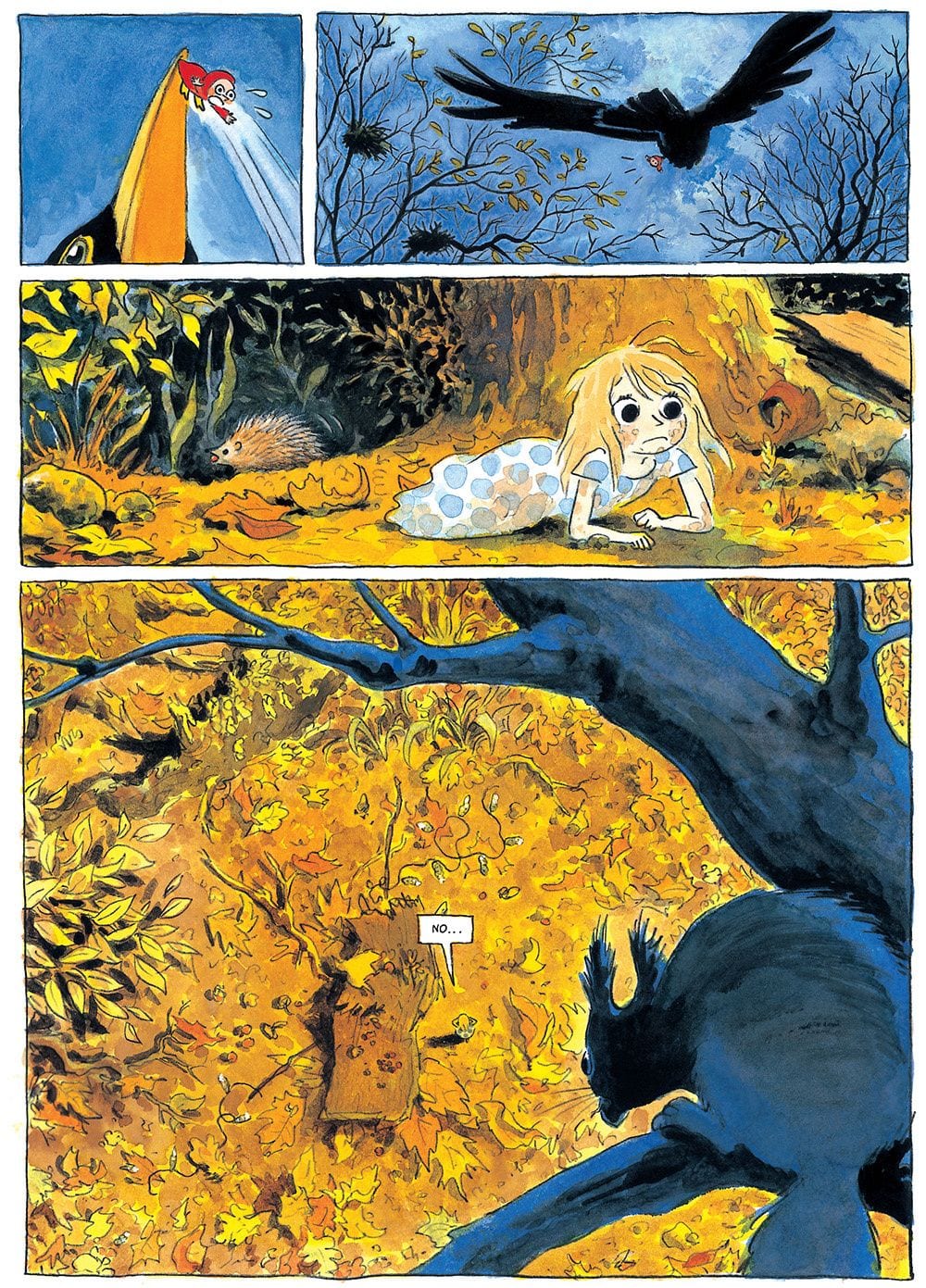

The pairing produces horrors. How will these innocent fairy tale folk survive in a real-world wilderness? They won’t. It turns out there are a lot of ways to kill a cartoon: cat, bird, bee, toad, ants, poison ivy, kite, puddle, starvation. The first death is most startling, but the gruesome effect never lessens in part because the death of a cartoon violates the logic of cartooning itself. How many times has Wile E. Coyote fallen to his would-be death only to have his flattened but endlessly malleable body rejuvenated for the next scene? The absurd proportions of most cartoons would make the function of internal organs impossible. And yet when one of Kerascoët’s cartoon characters attempts to be fed like a baby bird, the force of the mother bird’s beak down his throat widens and buckles his neck in standard cartoon fashion—but then his face is blood-soaked as he staggers away, apparently to die of internal wounds.

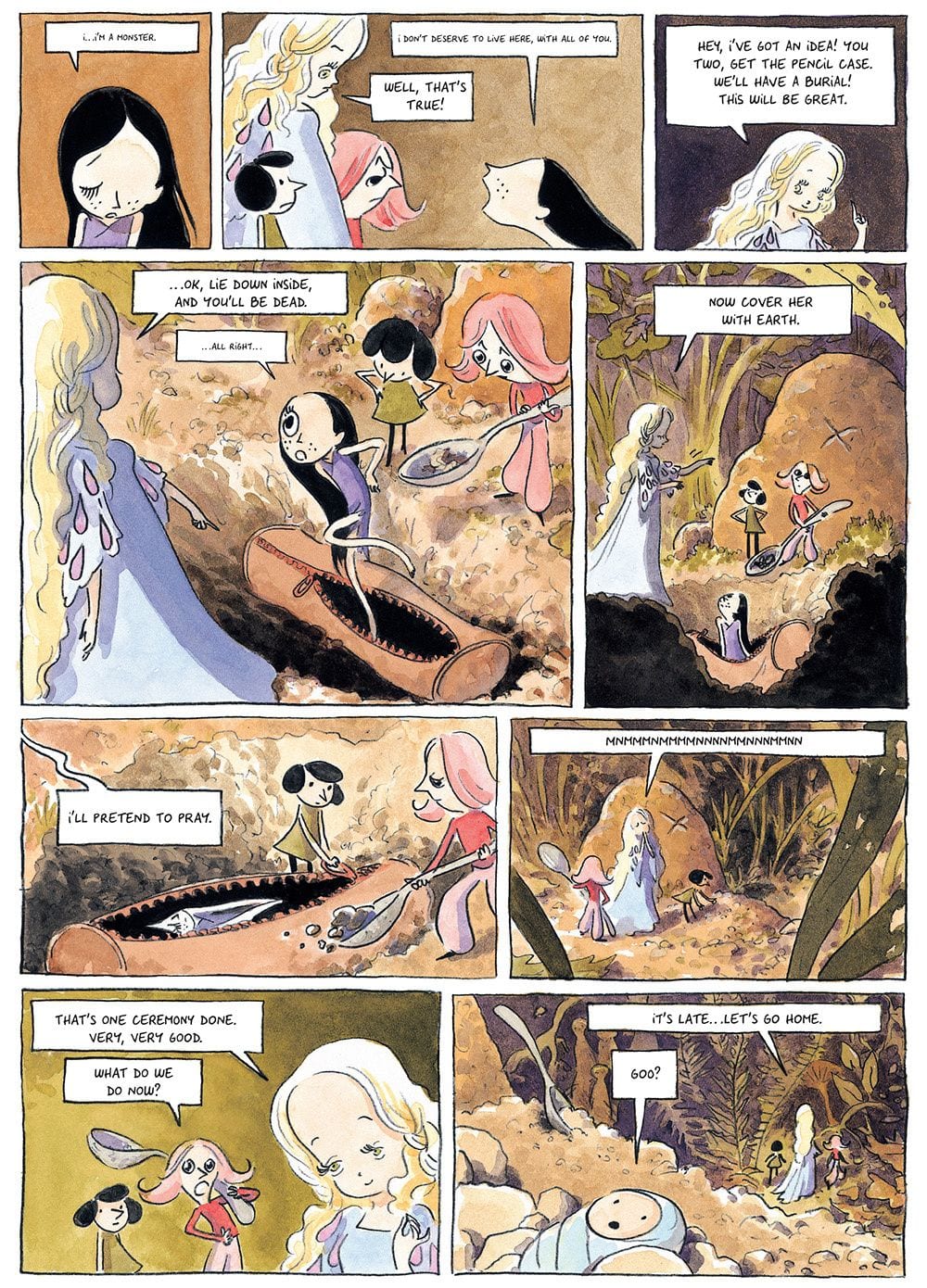

Though each death vignette is effective, the horror of Beautiful Darkness is more than the picking off of cast members as expandable as any in a Friday the 13th film. They are literally their own worst enemies. It turns out methods for murdering cartoons include abandonment, cannibalism, and live burial. But that’s not the disturbing part. While the apparent existence of naturalistic organs inside cartoon bodies is discordantly upsetting, the psychological ramifications echo deeper. It’s one thing to find the flow of maggots across your feet ticklish. It’s another to yank off the legs of a ladybug for fun.

“Things are not as they appear” is the ur-plot of most stories, but it’s especially true of horror: the corpse under Poe’ floorboards, the fangs retracted behind a vampire’s smile. Horror always waits just beneath the benign-seeming surface. It’s the difference between transformation and revelation. Did hunger make the giant baby doll eat one of her tiny friends or was the giant baby doll always capable of that crime? Worse, another friend protests before quickly returning to playing, the devoured friend apparently never a friend at all. The pleasant facade of these cartoons covers a moral abyss devoid of empathy and self-reflection. They are the novel’s only monsters.

And we’ve still not hit bottom, because the true plot question is whether Aurora, the kindest and most dutiful of all them all, will succumb—not to death, but to the darkness revealed by the collision of her cartoon world against a naturalistic one. It’s no spoiler to say the nature of her character remains radically ambiguous. When she helps the others to build shelters out of the dead Aurora’s notebook, someone reads the name and asks, “Who’s Aurora?” Aurora answers, “I am.” At first, I thought she was lying, maybe to prevent anyone from feeling qualms about stealing (this is well before the first murder), but the answer seems much more complex.

Is the cartoon Aurora a manifestation of the human Aurora? Is that why she cries at the sight of a fly hatched from her corpse? Was she and the others released by her death? Do all daydreams take physical forms when we die? Or is this a kind of afterlife? Has this cultural stereotype of childhood innocence died and gone to hell? This cauldron of questions are stirred most violently in a midpoint two-page spread in which the human Aurora wakes in sunlight, sits up from the forest floor, and wanders off—only for her motionless corpse to return after the page turn and the monstrous cartoon child who has burrowed into the cave of her skull to gasp awake, relieved that it was only a “nightmare”.

If you’re used to the blood splatter of slasher films or the simplistically evil monsters of supernatural thrillers, be warned: Beautiful Darkness covers an abyss of horrors far deeper.