For all of the semi-heroic

understandings of the goal of

authenticity in readings of Heidegger and Sartre,

we risk the monstrosity of the

all-too-human that Bellocchio’s

Alessandro represents.

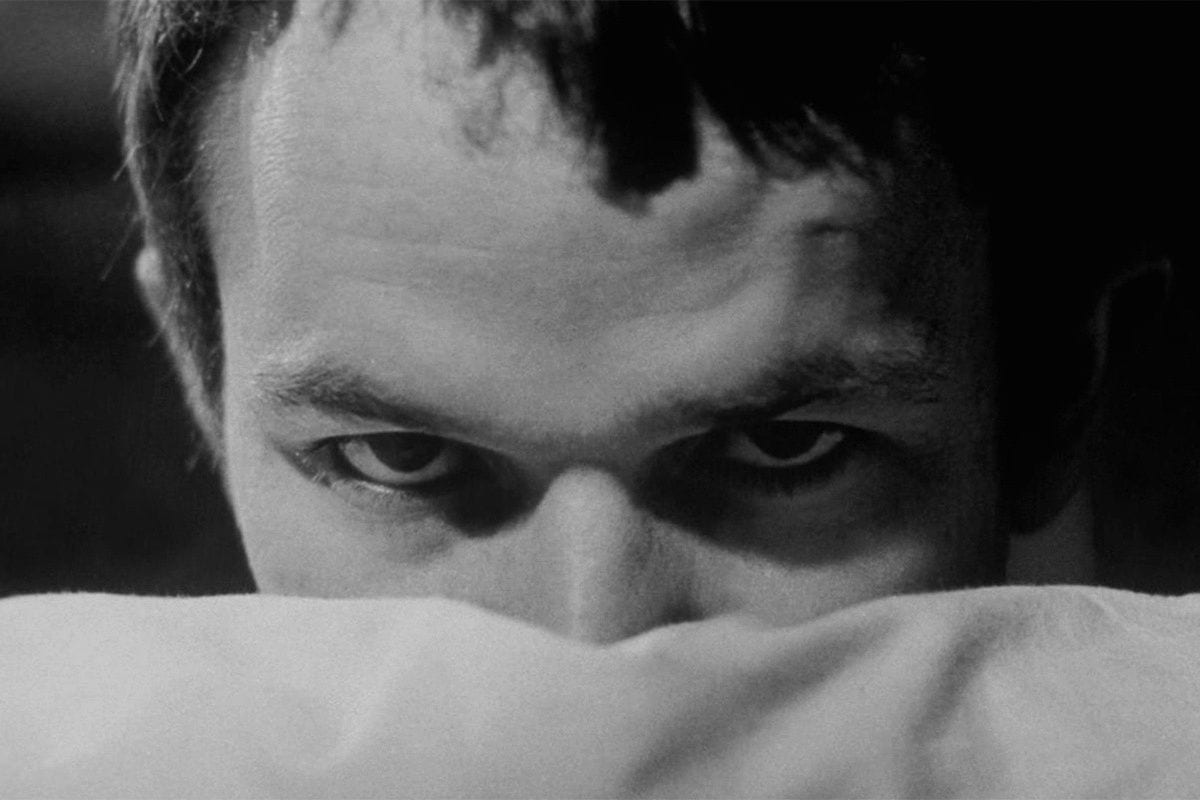

Marco Bellocchio’s 1965 debut film,

Fists in the Pocket (I pugni in tasca), capitalizes upon the director’s precocious and semi-controlled lack of discipline to breathe life into the suffocating surroundings and existence of a family cloistered in a provincial Italian villa. A son, Alessandro (Lou Castel)—brilliant but embittered toward a world he feels has left him disadvantaged and hopeless—decides his older brother Augusto (Marino Mase) would be better off if Alessandro killed himself. (IMDB)

But before he does, he wants his brother to kill his their blind mother (Liliana Gerace), their impaired brother Leone (Pier Luigi Troglio), and their erratic sister Giulia (Paola Pitagora). Often fancifully understood as an adumbration of the political unrest that would erupt in the 1968 mass demonstrations,

Fists in the Pocket is, to my mind, better interpreted as embracing the nihilism that inevitably lurks in the recesses of our sensibility when we face up to our alienation in a world that has no reserved or proper place for us.

Alessandro is the second son in a respectable bourgeois family in decline. The father is gone and never mentioned; his mother blind, dependent, importunate, consolatory and requiring consolation, infantile and infantilizing. Augusto supports the family and clearly resents his role, even while being unwilling to shirk it entirely. He longs to live in the city with his girlfriend, Lucia (Jeannie McNeil). He wishes to be away from the responsibilities and dysfunction of his family, whom he repeatedly reminds of their debt while adjuring them to leave him alone to enjoy whatever vestiges of a private life remain to him.

Alessandro and the youngest brother Leone are epileptic and require relatively close monitoring as their seizures (seemingly more frequent for Leone than Alessandro) are unpredictable and life-threatening. Leone has notable cognitive difficulties, is developmentally impaired, and yet rather perspicacious—he senses the danger present in his home without being able to determine its cause. Nor is he capable of escaping it.

Tunnel by Dariusz Sankowski (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

Giulia exudes a troubled and troubling air of sexual seduction in connection with her two older siblings. She writes threatening letters to Lucia(with text cut out from magazines in the fashion of a ransom demand), declaring in the manner of a jealous lover that Augusto is merely toying with Lucia’s affections. She encourages and seemingly indulges the incestuous lust of Alessandro, who writes her love poetry (which she gloatingly shows to Augusto). She later indulges his more physical demonstrations of desire and becomes complicit through assent in Alessandro’s murder of their mother. Her allegiances and ambitions remain inscrutable aside from a vague implication that she seeks to replace her mother as the abiding and central female figure in the household.

Although Bellocchio carefully rounds out each member of the family (aside perhaps from the mother, who appears to be more a symbol for the hypocrisy of the traditional adoration of the maternal), Alessandro soon emerges as the film’s central concern. Beset with tics and odd behaviors, Alessandro exhibits a bizarre physicality that suggests that his malevolent drives are not simply cerebral or bound up in an ethereal and locationless will. They are fully embodied, his very corporeality is invested with the senseless viciousness he brings to bear on those around him.

Most of these movements are of a strangely calculating manner. Early in the film, he leans back in his chair while at family dinner and stretches his arm out across a sideboard behind him. He returns to a fully seated position only to repeat the entire action—the leaning backward, the stretching of the arm, the caress of the wooden surface. The repetition and deliberation seem to be the points behind the exercise. When he enters rooms he often places his extended hand in front of his nose and then folds it over into a closed position and repeats the motion obsessively.

Later, Alessandro measures his brother’s desk with his hands, thumbs extended, placing fist over fist—measuring without purpose aside from the deliberate acts of repetition. Deliberation evidences the power of the will (here encapsulated in the motions of the body, not merely the disembodied desires of an intellectual will) while repetition suggests its efficacy. Obsessive repetition exerts control over a world that resists Alessandro’s desire for mastery; the measuring gestures attempt to reduce the world into something knowable and thus manageable.

Lou Castel as Alessandro (IMDB)

Alessandro’s physicality transcends these moments of obsessive compulsion, however. He lurches about rooms, pretending his legs no longer work as he drags himself across the space by propelling himself from one piece of furniture to the next. He crawls over tables rather than circumambulating them. He expirates and hisses in the manner of a cat—an expression, at times, of disdain, at others of mere boredom. In a striking early scene, he plays a record of lugubrious orchestral music, genuflects, then props two menacing daggers below his stomach as he hovers, stretched out on his bed. He plunges down, seemingly onto the daggers, in what appears to be a shockingly abrupt ritual suicide, (Bellocchio provides no immediate clue to dissuade us from this belief.)

The scene cuts away to Giulia lying prostrate in her bed. When we return to Alessandro, very much alive, he is performing a headstand. All of this pointedly pointless activity puts Alessandro on display as not only a body in motion, but a body utterly desirous of having its motions eventuate into some concrete result that eludes it. Alessandro acts, but he rarely accomplishes much—until he turns his attention to the annihilation of his family.

Alessandro’s rationale here seems simultaneously scrupulously pragmatic and absolutely abhorrent. The entire family invests its hopes in the older brother, Augusto, and in doing so have guaranteed Augusto’s unhappiness and ultimately his failure. The remaining members of the family, including Alessandro himself, are reduced to an unshakeable stagnancy owing to their utter dependency, their physical and mental impairments, their lack of wherewithal. Therefore, if the one member of the family capable of achieving something in life, of gaining some place in a world that seems to have cast the family as a whole into the slough of despond, can only succeed by being shorn of the rest of them, Alessandro suggests that this justifies the elimination of the hangers-on.

Alessandro raises the issue with Augusto, proclaiming—after silently rehearsing his pitch with exaggerated, repetitive hand gestures—that Augusto, being the only one capable of achieving and maintaining some semblance of freedom, will only be liberated if Alessandro drives himself and the other members of the family off of a cliff during a family outing. Augusto doesn’t take Alessandro’s suggestion seriously, laughing it off as some kind of joke. Alessandro fails his driving test but lies and claims he passed. He then attempts to carry out his plan—in accordance with his obsessions, he has here measured out the future and determined that it functions properly only with the demise of his family aside from Augusto.

Our Inhumanity and Depravity

But surely such calculations are monstrous, inhuman. And yet, is it possible that we misuse the term “inhumanity”? The term proliferates, of course; we are never short on examples of man’s depravity. We employ the term to characterize people (humans) who somehow behave in a manner we believe contradicts or runs against the grain of what we would like to consider the essential nature of humanity. But there is a great deal of idealization at play here. We allow “inhumanity” to stand for all of those things that humans do but that we would rather they did not. These things violate our certitude of the rectitude involved in being human, that run afoul of the bare minimum of righteousness that we hope is essential to a human being (the avoidance of violence, murder, and cruelty). To be “inhuman” is to occupy a kind of lack. A human (properly, essentially) ought to have certain characteristics, to be a certain way, and the “inhuman” is bereft of those qualities, and exists in a different, aberrant way.

Most often, of course, we are concerned with “man’s inhumanity to man” or perhaps also one’s inhumanity to animals with whom we partially identify. Murder is inhumane; one can treat cats and dogs in an inhumane manner; but we rarely consider our “inhumanity” with respect to the environment at large and discussions of the “inhumanity” of butchers and farmers is relatively rare (although not entirely absent). In short, our concern with “inhumanity” generally revolves around our concern with keeping the bounds of our own humanity intact; the cruelty of the other isn’t merely distasteful (like poor hygiene, or disgusting eating habits), but rather a potential personal threat.

Hidden within that threat is the implicit assertion that I might be the same way, I might be equally inhuman, given the right provocation of circumstance. My use of the term “inhuman”, then, is not merely derogative, it is self-protective. It dehumanizes in order to demarcate the boundaries that purportedly separate me and my values from what is putatively considered the unthinkable.

The problem here is that the term “inhuman” identifies human beings doing what human beings often do but that we wish they would not. “Man’s inhumanity to man” is therefore an assertion packed with idealistic assumptions that don’t hold up under scrutiny. The depredations of war, the wanton acts of casual cruelty, the violations of predation, the exertions of power over the vulnerable—these are not “inhuman” from a statistical or historical viewpoint, they are all-too-human and all-too-common.

The fact of the matter is that there is precious little that we can, with any certainty, claim is essential to being human outside of the biological, the fact that we are classified as the species homo sapiens. If we are to lend credence to one side of a long-standing argument within psychology that insists alongside Abraham Maslow (the psychologist that developed the theory of the “hierarchy of needs“) that human beings have no instincts past early childhood insofar as instinct cannot be overridden or modified, then there are no essential behaviors involved in being human that transcend what it means to be an animal (that we must eat, sleep, etc.).

As Jean-Paul Sartre insists, existence precedes essence. We are and then we work toward what we are or what we might become. Of course, as Sartre recognizes in his reading of Martin Heidegger, matters are not that simple. Heidegger articulates the complexities attendant upon a human being’s being in the world (what he terms Dasein—or “being there”). We are “thrown” into a world not of our choosing, with all of the expectations, assumptions, ideologies, possibilities, and social roles of our era, nationality, racial/ sexual/ gender standing, and family. We don’t forge meaning for ourselves out of nothing, nor are we simply taught all of these assumptions and roles. We live them before we consciously grasp them at all (and some we may never consciously grasp).

That thrownness is always-already our tie to the past, to the givens of our lives and circumstances. By the time we are attendant upon a present, we are already suffused with a past. Moreover, our experience of the present involves the fact that we are in a world with others, we are always in a state of being. With that requires that we take care of what is of concern at the moment. Finally we also, as beings that are not defined by an essence that we cannot modify, are always involved in a future. Dasein is always concerned with its various projects—what it wants to become. We draw on the givens of our past to take care of matters in our present moment for the sake of what we hope to become.

Our Desire for Nihilism

Paola Pitagora as Giulia Lou Castel as Alessandro (IMDB)

The nagging consequence, for many, of defining the human as that which has no essence—that has nothing that it has to be but is defined by the various things it might become and the manners of becoming so—is nihilism. If the givens of our thrownness are not necessarily an immutable moral foundation, if our concerns for being-with others are not grounded in divine law, and our hopes of the future do not take the shape of eschatology, then all values may be revalued or devalued, all moral norms are merely prescriptive and can be eschewed. Our being-with others need not be based in mutual respect, then, but can just as easily be founded upon mutual predation. For all of the semi-heroic understandings of the goal of authenticity in readings of Heidegger and Sartre, we risk the monstrosity of the all-too-human that Alessandro represents.

Alessandro finds himself thrown into a world that offers him no respite, no proper position within it. (This is true of all of us according to the Sartrean dictum.) He feels cheated; he seeks solace in his admiration of Augusto, in his incestuous desire for his sister. He perceives that his thrownness—his family, his condition—makes any projects for the future that he might hold dear impossible. Of course, this may be misprision (surely there are options for him), or more likely it derives from his unwillingness to stake out a suitable project when he feels that, given that his family clearly once enjoyed a vaunted social standing, he is owed a comfortable place in society without earning it.

The reality and justification of his felt displacement matters little; he feels it and acts upon it. Given what he regards as a hopeless condition, his being-with others becomes a frenzied determination to empty the world of what he recognizes he ought to value but that he finds bereft of worth—the members of his family and his own existence. His projection into the future then becomes the elimination of the objects of his present concern. In a reversal of the Leibnizian question (“Why is there something rather than nothing?”), Alessandro seeks to make nothing out of the something present to him. He longs to annihilate his world and whatever vestiges of meaning it may contain in preference to the void, meaninglessness, and nothing.

The film doubles down on Alessandro’s nihilism by skewering the two primary traditional sources of value and moral grounding: religion and family. Before his fake suicide (a profanation in the eyes of the Divine), Alessandro genuflects. His view of the world is devoid of any divine plan. Indeed, he usurps both ends of the divine relationship: he decides upon life and death (the divine mandate) but he also condemns himself to annihilation. He is at once God and the profligate sinner condemned to suffering and demise.

Indeed, he revels in his usurpation after he murders his mother. At her funeral, he blithely dismisses those hired to chant and pray over her corpse so that he can sit with his victim. His fists tighten as he looks down at her. He impiously props up his feet on the edge of the coffin, then vaults over the coffin in imitation of a gymnast; he chats desultorily with his sister, describing his mother’s death as a “great opportunity” that has inspired everyone to try to take financial advantage of it. He then divulges to his sister that he murdered their mother. Outside, choirboys frolic about with abandon in the yard of a house observing a wake.

From Whence We Are Thrown

(IMDB)

If Fists in the Pocket targets religion as an ineffective transmitter of value and meaning to life, it positively skewers the family. Our thrownness is perhaps most firmly grounded in our family life. Of course, we are born into a specific era, in a specific country, in a region of that country, in a neighborhood and in a social class—and we imbibe all of the assumptions and ideologies inherent in those places. Even if we may come to reject those assumptions later in life, we don’t learn them as though they are just bits of information—we live them. By the time we are ready to question such normative ways of viewing the world, we already inhabit them.

But all of those levels of our embeddedness within a specified thrownness are most proximately experienced by us within the family (or whatever substitute family shapes our development). Our sense of politics, nationalism, gender identity—our formative sense of self—is established in constant reference to the manner of living we absorb in our home among the members of our family.

The place of the home (or the home as fundamental place) orients us in relation to the world. The home is the primordial place in our foundational experience—and remember that we are always emplaced, we are always in place—someplace. We can only be somewhere; to be nowhere is not to exist. We inhabit place. Notice I do not write “we inhabit space”. That’s true too, of course, but it is not the same thing. Space is anonymous and featureless. We move within space, sure, but as a secondary, abstracted consideration. Places are filled with things immersed in an array of deep interrelationships.

The room I sit in now is not merely an empty space with a variety of things scattered about it. Rather, the room is that collection of things (not individually but as a web of relationships—some congenial, some fraught) along with the experiences I’ve had in this room, the history of it, its position within the city, its peculiar manner of being. I don’t add everything together and get the room (except in an act of analytical thought, an act of brutish abstraction); I live in the room and the things in it (and my experiences, and its history, etc.) show up to me as meaningful precisely in the context of being in that room. In short, I don’t see a place because of the things in it. I am able to grasp those things because they show up to me as part of a place.

Crucially, we move through the places of our world and the childhood home is our primordial place, providing our formative understanding of what it is to be in place, to belong to a place. And since we are beings that can only be in place (and are intensely embedded within place), our childhood homes teach us how to be in the world. As Heidegger insists, no matter how freely we might wish to recreate ourselves, to project ourselves into a liberating and unknown future, we are always connected back to our thrownness and the most penetrating form of that thrownness, I suggest, is the family ensconced in the place we call home.

If the home is the most pervasive place, with all of its attendant power to orient and provide meaning, then we see that Alessandro seeks to empty it of that efficacy, of that significance. He does this quite literally: first, by killing the matriarch (the symbolic head of the home and the guarantor of its capacity to nurture, to shelter, to console), and then by emptying the house of her possessions. Alessandro and Giulia, in the aftermath of their mother’s burial, begin heaving her furniture and other objects out of her room, over the balcony, and into the yard. The chifferobe and chairs and portraits are tossed unceremoniously from the house.

Or perhaps ceremony is exactly what is at stake here—but a ceremony of destruction, the celebration of the nihilistic urge to dispense with a loved one who had become inconvenient in a world that, for Alessandro, is replete with inconvenience. He and Giulia set the furniture ablaze: a funeral pyre to commemorate the beginning of the end that Alessandro (unbeknownst still to Giulia) believes he has set in motion. If things take their meaning from being emplaced within a site of significance (no place being more significant than the childhood home—Alessandro’s only home), then Alessandro seeks to eradicate meaning by emptying the home. If a place accrues meaning from its repletion, from the complex interrelationships among the things that occupy the place, then Alessandro seeks to give rise to the void. He longs to replace something with nothing.

Nihilism, of course, is difficult, perhaps impossible, to sustain. Every action taken supposes some kind of purpose—however seemingly arbitrary—and thus implies some sense of value (even if grounded in the perverse zeal for devaluing what is meaningful). The joy he takes in destroying his family reveals that Alessandro values that destruction, that he becomes exhilarated by his malevolent power. The strange repetition in his bodily movements decrease as the film progresses, as he begins to feel increasingly in control.

After the murder of his mother, he no longer wants Augusto to be the sole beneficiary of the fortune Alessandro feels he has earned through murdering the matriarch. The urge to destroy, to clear space for himself by eliminating the place of the home, becomes a value unto itself. In place of something, Alessandro comes to desire the nothing, the lack of what was, the absence of former meaning. He abides by that nothing, that lack.

The lack is, of course, the defining characteristic of man under the gaze of existentialism but as something to inspire creation, forging a new (albeit precarious) something. For Alessandro, any something is to be reduced to nothing. All meaning has value for Alessandro simply as something to be destroyed. Why is there something instead of nothing? Perhaps it doesn’t matter. Because we humans (with all of our capacity for the so-called inhuman) are able to make nothing out of it.

Criterion Collection has recently released a Blu-ray edition of Marco Bellocchio’s Fists in the Pocket (I pugni in tasca), his first film and a work that he arguably has been unable to match since. It is a stunning debut and a must-see for anyone interested in the stark shift Italian cinema experienced in moving from the post-realism phase of the 1950s into the experimentalism, social commentary, and surrealism of the 1960s. The new edition comes with interviews with Bellocchio, Lou Castel, Paola Pitagora, the editor Silvano Agosti, critic Tullio Kezich, scholar Stefano Albertini, and director Bernardo Bertolucci.