“I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color,” said 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick after not standing for the pre-game national anthem for the first time in 2016. “To me,” continued Kaepernick, “this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way.”

Kapernick’s fictional counterpart in Ben Passmore’s graphic novella Sports Is Hell is less eloquent. When asked by a reporter, “Do you intend to kneel during the national anthem, despite many people calling it disrespectful?” Birds wide receiver Marshall Quandary Collins simply answers ,”Yes.”

Passmore’s sportscasters (who have logos for heads) call that single response “inflammatory”. Collins seems anything but.

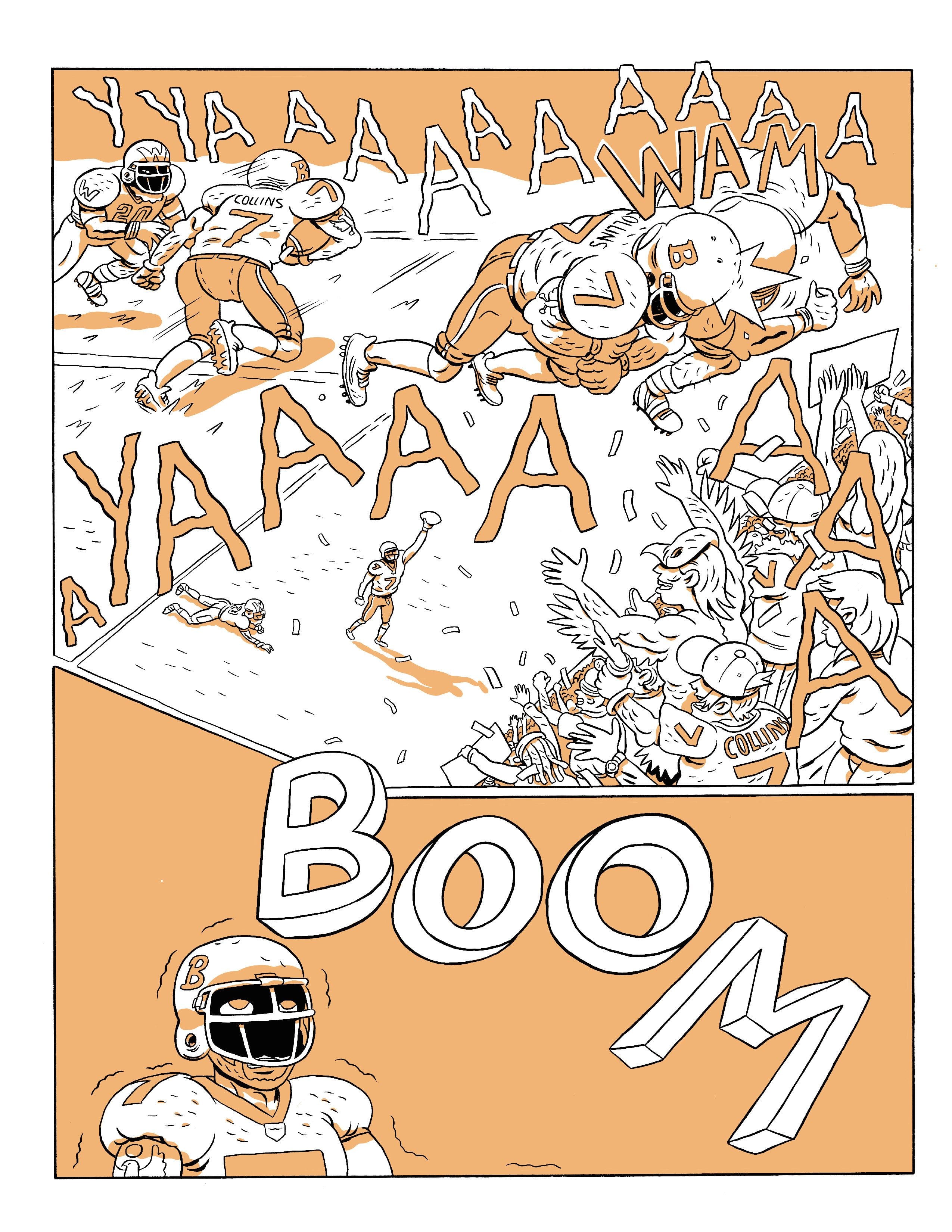

Passmore draws oversized beads of sweat across Collins’ face. His eyes shift with every noise rising from the stadium crowd. On the field, Collins looks like a man who’s afraid he’s about to be shot. Since Kaepernick was taunted with death threats, this is one of the least farfetched things about this apocalyptic parody of racism in the US.

Passmore’s Sports Is Hell is about football in the sense that Melville’s Moby Dick is about seafood. Which means there’s plenty of football, including Collins’ Super-Bowl-winning touchdown reception. There’s also a later post-penalty reenactment performed at gunpoint in the courtyard of an all-white condo complex while militias battle in the burning streets. As one of Passmore’s anarchist characters explains: “Football teams are just a stand-in for identity.”

(courtesy of Koyama Press)

Despite the cover image—a weapon-toting football player standing in a field of skulls and debris—Passmore begins the novella with a few roughly realistic vignettes that imply that the story world is our world, only slightly more so. Children shoot pretend guns in the street until a bowtie-clad neighbor scolds them. But with his warning he points at a police car and says, “You don’t play with them. If you point something at them make sure it’s real.”

A page later, a man carrying a We The People sign is trying to catch a bus to a Black Lives Matter protest. A white woman asks the black stranger if he wants some money, and then her boyfriends exclaims, “We love black people!”

Turn the page and we’re with a different couple in a bedroom planning for the after game celebration. Only they’re packing hammers and spray paint in hopes of a literal riot, not that “dusty nonviolence shit” of Black Lives Matter.

Though the tone is already moving toward farce, the ensuing riot begins realistically enough, with roving street crowds and a toppled can of burning trash. The ambiguous merging of political protest, pointless vandalism, and football party seems about right too—even when a protest organizer starts shouting for the city to unite behind the leadership of Birds wide receiver Collins.

Of course the police soon open fire on the unarmed crowd. The police retreat before the Nord Football Club for Racial Purity starts shooting too, followed by another team of neo-Nazis, the Holy Nation of Second-String Quarterback Sherman Muck. Did I mention the other Super Bowl team is named the Whites?

(courtesy of Koyama Press)

Like most cartoon commentary, Passmore’s doesn’t suffer from subtlety. Though the cast is mostly black (all those folks we met in the opening pages get thrown together like zombie survivors in a boarded-up mall) the white characters are on the receiving end of most the humor.

Passmore’s two-tone color scheme—black and an oddly appropriate beige—reduces but doesn’t obscure the increasing gore. His characters are also only mildly exaggerated, and since their universe obeys the same basic laws of physics as ours, cartoon bullets do non-cartoonish damage to their almost-proportional bodies. Yet still, most of the cast survives.

To say the novella’s ending is abrupt would be an understatement. That’s clearly Passmore’s intent. This is just another day living under US racial dystopia. Basketball season probably won’t be any different.

Meanwhile the real-world Kaepernick still isn’t playing football even though it’s been a year since he came to a confidential settlement and withdrew his lawsuit. The lawsuit accused the NFL of colluding to prevent his being hired after he became a free agent in 2017. According to the President of the United States, Colin and other players who take a knee during the anthem are at fault: “They’re ruining the game.”

With that kind of cartoon-like reality for a national backdrop, farce may have been Passmore’s most realistic option.

(courtesy of Koyama Press)

Works Cited

Draper, Kevin and Belson, Ken. “Colin Kaepernick and the N.F.L. Settle Collusion Case“. The New York Times. 15 February 2019.

Associated Press. “Trump says NFL should fire players who kneel during national anthem”. Los Angeles Times. 22 September 2017.

Uncredited. “Kaepernick anthem protest: Player had ‘death threats'”. BBC News. 21 September 2016.

Wyche, Steve. “Colin Kaepernick explains why he sat during national anthem”. NFL.com. 27 August 2016