When Jason Lutes began sketching the first pages of his acclaimed comic series Berlin back in the mid-’90s, he had no idea it would take until 2018 to complete it.

The series, which depicts the rise of the Nazis in Weimar-era Germany between the two world wars, is finally finished. The last issue hit store shelves in March, and the final completed collection — Berlin Book 3: City of Light — will be published in September, along with a full three-volume edition. Lutes hasn’t been pursuing it single-mindedly—he’s published shorter one-off works in the intervening years, and has forged an academic career as well—but completing the two-decade opus affords him an opportunity to reflect on the significance of this literary achievement.

He says he’s happy that it’s finally done, and his wife and children are happy too. His students are happy as well. For the past several years he’s been working at the Center for Cartoon Studies, a two-year MFA program in Vermont, and his students have followed his progress closely. For them, he says, laughing, it’s proof positive “that these big books get done, even if they get done very slowly.”

Lutes always yearned to be a cartoonist. He shares a prophetic self-portrait he made at the age of ten, in which he imagined himself a cartoonist sitting at his desk agonizing over late deadlines and overdue bills. It’s a career he pursued doggedly (with the exception, he sheepishly admits, of about one year in art school, when he briefly decided to put comics aside – “luckily I quickly discovered that no… comics are my thing and comics are worth it!”). Forty years later, he’s achieved his dream. He’s an associate professor at the Center for Cartoon Studies, where he teaches comic storytelling. But he cautions aspiring comics artists that the field, while rewarding, remains a challenging one. While the mainstream industry assigns teams of writers, pencillers, inkers, colorists, and letterers, independent alternative comics artists wind up doing all these tasks themselves.

“It’s really hard work, because when you’re writing a comic, a narrative comic, you’ve got to be the writer, the set designer, the costume designer, all of the actors. And on the one hand it’s wonderful because you have complete control over all that stuff — it’s all yours, it’s your little world — but it’s also a challenge to be able to do all of it because it’s a variety of different jobs, really. That’s one of the reasons it can take a long time to produce the work.”

Lutes would know. Few writers anticipate, when they embark on a project, that it could take them decades to finish. But Lutes adopts a tone of serenity as he reflects on those years.

“No regrets. I’m not somebody who wishes I could have done something differently,” he’s quick to say. But as he reflects on the process of writing, he admits he hadn’t originally realized that some of the decisions he made early on – how big the pages would be, the level of artistic detail – would bind him for the next two decades, if he wished to maintain consistency.

“Moving forward, in order to get work done more quickly, I’m generally speaking just going to draw smaller and simpler. Those are the two big lessons I’ve learned.”

Above all, he says, he feels a sense of relief and excitement about what comes next, and being able to move forward with projects he’s had to put on the backburner for the past two decades.

That means no more 600-page epics, at least not for now. He has in mind to produce a series of four 96-page self-contained stories. The first will be a western, written from the perspective of a girl of Mexican descent in Arizona in 1865, at the tail-end of the Civil War.

“I’m trying to put aside all of my generally received ideas about what a western is, and I’m trying to look at this particular time and place… and the incredible confluence of European forces from the east, the Mexican Spanish forces from the south, Indigenous people… the Arizona territory was largely unsettled, Phoenix was a collection of tents at the time, and I’m fascinated with that area of history.

“It’s very similar to my approach to Berlin, which was: what was it like for the person on the street? I’m not interested in the sheriff, I’m not interested in the outlaw, I mean those are interesting but I’m more interested in the other people who were living then. So it’s going to be focusing on characters that you may not think of when you think of a western.”

The Lutes Method

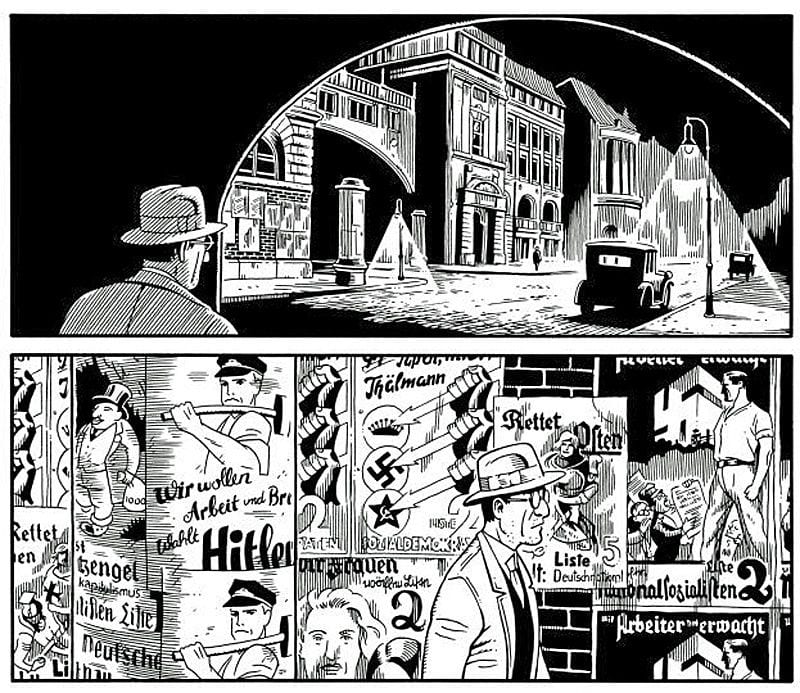

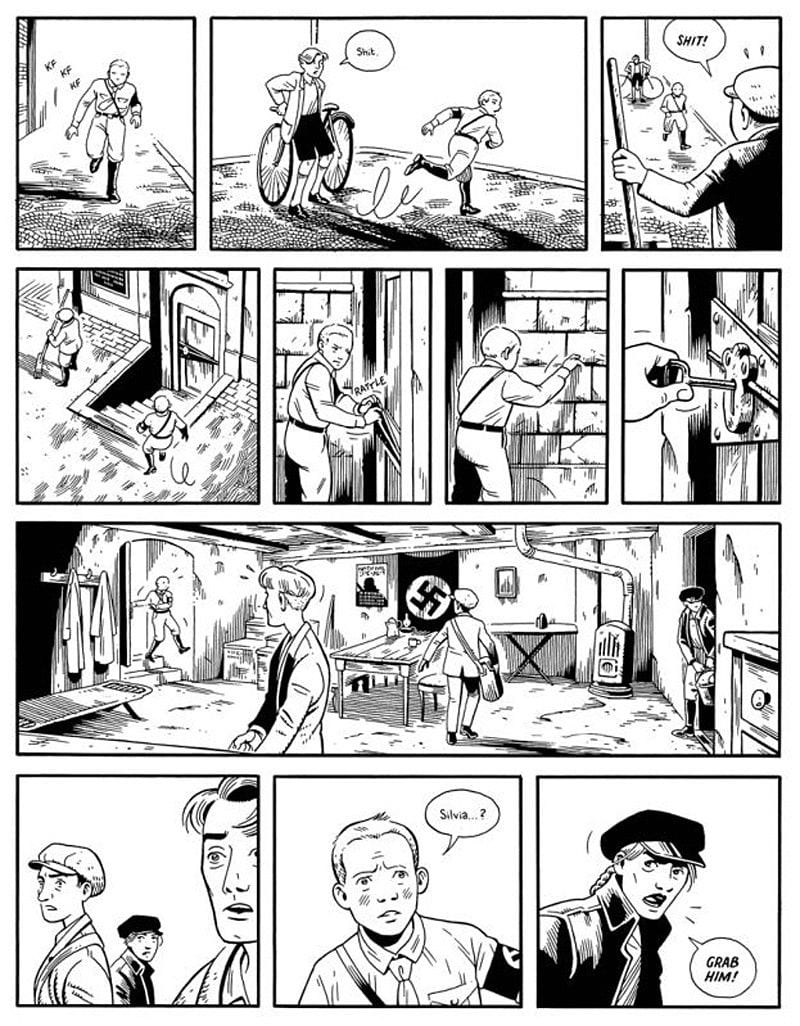

The approach Lutes refers to is what makes his work so compelling: an approach to history that adopts multiple vantage points from everyday protagonists on the street, as opposed to depicting elites and their machinations for power. His primary sources are not the texts of the rich and powerful but everyday popular culture, which help him form a sense of what the period was like for those living through it. Rather than studying academic treatises on what life was like in Weimar Germany, or on the causes which led to the rise of the Nazis, Lutes immersed himself in the primary popular culture of the period. His aim was to produce a sense of what everyday life was like for the average German.

One of the unique and outstanding qualities of Berlin is the manner in which it humanises the everyday experience of a broad cast of average, working-class Germans. An ethos of the everyday pervades the text, and distinguishes it from standard historical works that concentrate on specific period elements: anti-Semitism, say; or the rise of the Nazis. That’s all in there, but it’s part and parcel of Lutes’ effort to create an authentic sense of what it was like to experience everyday life in the period.

“That approach is not something that I have seen in the existing work on the period. There’s tons of scholarship and tons of history, there’s novels written at the time and historical fiction that tackles stuff, but generally the historical fiction that I’ve seen is more plot-oriented, whereas what I’m trying to do is to explore the time and the place through the characters.

“It’s very much a feeling of actors on a stage, or puppets that I’m playing with and making talk to each other. Through their experiences, and through my imagining them as people and what they encountered in their day to day lives, I’m exploring that time and place. And trying to understand it, because I had a terrible high school education when it came to history, and I went to art school after high school so I didn’t have much time to pursue that academically. So it’s very much me exploring and learning about the Weimar period. I wanted to know how World War II and the Holocaust could possibly have occurred.

“It wasn’t until I was about 200 pages into it that I realized that what I was trying to do was understand this time in history personally,” he reflects. “For me, it was a self-education and an exploration of this time and space.”

Comics Offer a Unique Way of Writing About War

Lutes, participating in an exhibition about war in comics which took place in Newfoundland, Canada this summer, took some time to reflect about the unique ways in which comics enable us to write about war. He slips easily into the instructor-mode, and it’s easy to see why he’s a popular teacher at the Institute for Cartoon Studies.

Comics, he explains, are the product of a lineage of mark-making stretching back 30,000 years, to the dawn of human art. As mark-making became more sophisticated, it evolved along two streams: one aiming to reproduce the world as realistically as possible, and one which used marks in an abstract and symbolic fashion.

“So on the one hand things evolved to become more representational, and then on the other hand more abstract… to the point where on the abstract they came to be phonetic symbols and part of the written language… What comics does, is it takes those two extremes — it takes the representational and the abstract — and it recombines them.

“There’s this thing that happens in between the word and the picture when you put those two things together, where the reader closes that gap and makes that connection. It’s the same thing that happens between two panels on a comic book page. It’s up to the reader to make the connection between those things. And it’s a very unique aspect of comics, in that the reader is creating the synapses between these different elements of the medium.

“There’s a level of engagement, and a level where you as a reader are able to fill in the gaps on a thing. It’s much more participatory. The thing is a little bit yours, and we do that with all art, but comics has particular conventions that are set up to actually encourage that. So whether you’re depicting war or intimate human relationships, there are ways that you can use that medium, use that power, to create a sense of a place or an event or an experience that is different than you can do with prose or film or poetry. Comics is really unique in the way that it can depict that, the way that it engages the reader’s imagination is different from other media.”

Comics articulate lived experience in ways that are distinct from the presentation of everyday life in other media, as Lutes points out. That means they represent some aspects of life better than others. Lutes observes, for instance, that it’s hard to emulate the speed and immediacy of film with the comics medium. On the other hand, comics lend themselves more successfully to portraying larger, more holistic scales of meaning.

“If you think about Saving Private Ryan and the famous storming of the beach scene — which is very much you-are-there, using all of the power of film to put the viewer on that beach with bullets whizzing past their head — and that visceral experience, comics can’t do that. There’s always going to be some distance, because you’re looking at these little boxes on a page and you’re always aware of the concrete aspect of it. So it can’t give you that direct visceral experience that film can…

“There’s this kind of distance to it which is both a strength and a drawback. So when you’re showing something like a complicated battle, or somebody’s experiences in the trenches, or someone sitting at home receiving news of a dead loved one, you can use the medium to emphasize certain aspects of that. Often there’s a kind of objective distance that comics give you. You can stand back and look at it in a way and consider the whole in a way that you can’t with film.”

One of the challenges of anti-war statements through media and popular culture — especially visual or musical forms — is that works or excerpts thereof can often be appropriated to convey the opposite message. All too often the anti-war message is lost or the work is appropriated in ways that produce the opposite effect than it intended. Artists find their work appropriated or objectified in ways that glorify war, instead of opposing it or challenging it.

The comics medium has also produced some tremendous anti-war masterpieces—books which convey the horror, futility and pointlessness of war, along with the immense pain and cruelty that accompanies it, in profound and powerful ways. Some well-known examples include the work of Shigeru Mizuki (Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths, Showa), Art Spiegelman (Maus), and Joe Sacco (Palestine, Safe Area Gorazde), to name but a few. And while there are certainly comics artists who do use their pen to glorify war, it seems that there’s something about the unique blending of the abstract and the representational which makes it more difficult for the message to be appropriated and turned.

As an artist whose work very much critiques the rise of militarism in pre-war Germany, Lutes finds a distinction between the anti-war messaging of comics and that of other mediums.

“Absolutely. I think there’s also an inevitability to it, there’s often that slow-creeping horror or realization [which] is something that is a great aspect of the medium. I went and saw Platoon when it was first released and for me it was a really horrifying experience because Oliver Stone was really trying to show you this is what Vietnam was like, but two rows back there was a group of guys that were cheering and hooting and hollering at all the shooting and killing. That was a perfect example to me of how it is a double-edged sword. Putting something up on a screen does glorify it, regardless of what you’re actually showing.

“It’s less easy to glorify things in comics. You can still do it, and there’s plenty of people that do, but there’s always a kind of distance that can help the reader understand things a little more in context, and give them a little more awareness of everything leading up to a point or following a point. So it’s not as easy. You can certainly set out to manipulate people in a particular way, but I think it’s harder to actually manipulate people’s experiences in comics. You can direct them, you can suggest, but it’s much harder to really seize control of their senses and emotions.”

Resisting Today’s Fascism

The quest to understand what led one of the world’s most progressive states – pre-Nazi Germany — to lurch into genocide and totalitarianism has added valence in this day and age, with some drawing parallels between the United States under a Trump administration and the collapse of democratic society in Weimar Germany. Lutes says that when he started working on Berlin, such parallels might have seemed fanciful, but a lot has changed in the interim years.

“I started this book in 1996 based on this desire to know about history but also understanding that these forces were still present — all over the world, but in the States even at the time I knew there were several hundred white supremacist organizations around the country. Seeing day-to-day racism and things like that in North American culture was just part of the way I understood the world. So looking back at history and seeing these same forces at work, like xenophobia and scapegoating… Things are hard for some people so they want to blame somebody else. Instead of taking responsibility for themselves for their difficulties they want to point the finger at other people and feel more powerful and more control by subjecting others to whatever controls they can manage. I think there’s this basic underlying human capacity for those things, which has always been with us.”

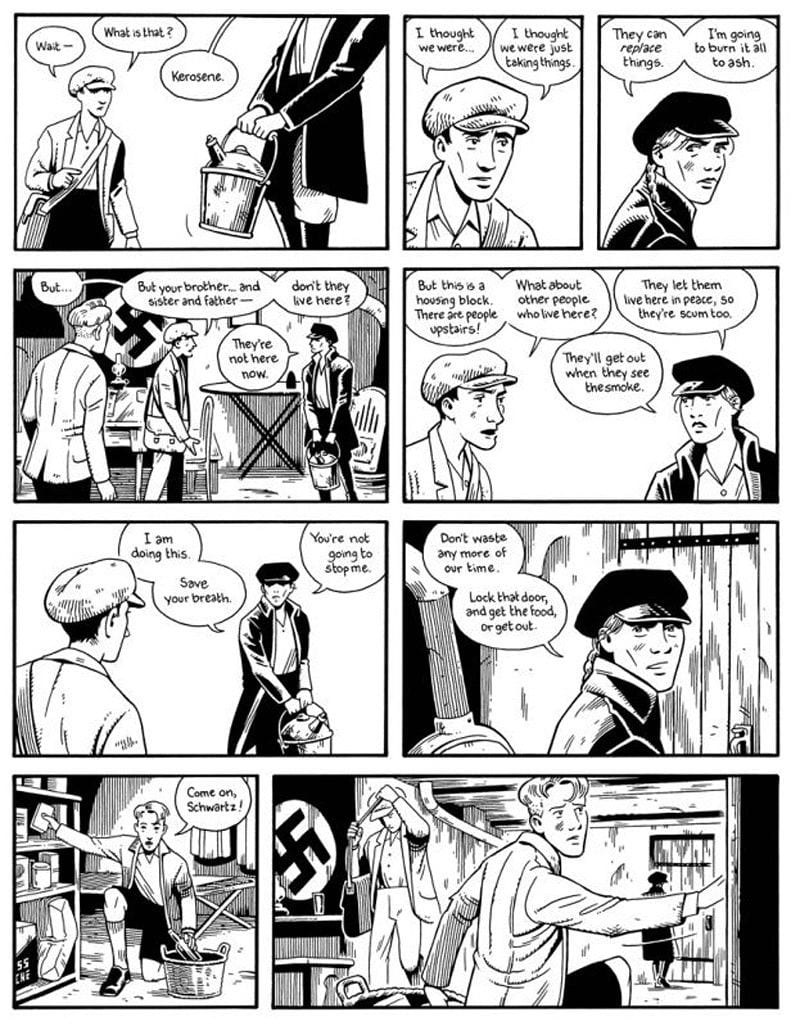

How should we respond to xenophobia? For Lutes, his effort to humanize the extensive cast of characters in Berlin even extended to Nazis. Rather than simply vilifying them, he felt it was important to portray the inducements that lure people into setting aside their values and falling under the sway of populism, hatred and anger. Doing so, he reflects, is a vital part of understanding the continued lure and attraction of xenophobic populism, which pervades the present era as well.

“I try to treat all of my characters as human beings, I try not to be stereotypical in my presentation of them. So characters in the story who are Nazis, I try to think of them as human beings and consider why they made the decisions they made and why they feel the way that they feel.

“I mean right now, in these times when fascism rises, I think it’s important to punch Nazis. It’s important to take action. Because if an existential threat is posed then that threat must be met. In between those times [however] I feel like those people who are so discontent and unhappy and angry need to be addressed. The forces that drive that anger need to be addressed. And not in a punishing way, but in a way that will help those people out of those bad places that they’re in. Because that’s the only way forward, really. It’s either that or war – civil war or international war. Those are the two choices that we’re faced with.

“When the threat is imminent, I feel that it must be met with force, but when it’s not, and we’re in between these flash point times, I feel that those deeper issues need to be addressed. I’m raising two kids in my country right now under the Trump presidency, in a climate where so many values which I consider to be basic and human and decent are devalued and there’s attempts to basically wipe them out or erase them or discount them. So in a lot of senses my work feels very relevant and real to me. I’m not just looking at the past and looking at this isolated thing, this little thing we can look at at a distance and observe — it’s very relevant to us today. The whole story takes place over a four-year span for the characters, but it took me 23 years to write and draw it, and the last five years with an increase of visible violence against African-American people, and this rising tide that Trump then kind of opened the floodgates for. I’m not surprised, because I’ve known those forces are there, but I’m kind of shocked to see it so nakedly exposed.”

Lutes has hope the US can rise above its current challenges.

“I do. And one of the reasons is we’re such a big country. Compared to Nazi Germany which was very small and contained and very homogeneous relatively speaking in terms of its culture, I think we stand a better chance of doing something about it. It’s incredible the amount of damage that’s been done already, it’s like an active dismantling of the instruments of democracy and when you just look at the people — the Trump appointees — and what they’ve done, they literally are just taking apart the structures that exist and making life for the people on the lower rungs even worse and for the people on the higher rungs even better. Every day it’s a new horrific surprise, which would be comical if it wasn’t actually affecting people’s real lives the way it is.

“But there is a real resistance and I take heart in that. And because I have kids, I really have no choice but to be hopeful for the future, so I choose that. One of our great strengths as a country is our diversity, and the alliances that are formed between different groups of oppressed people is very heartening and encouraging. So I do see a light at the end of the tunnel. But it might be a pretty long tunnel.”