In his definitive history of the English folk revival,

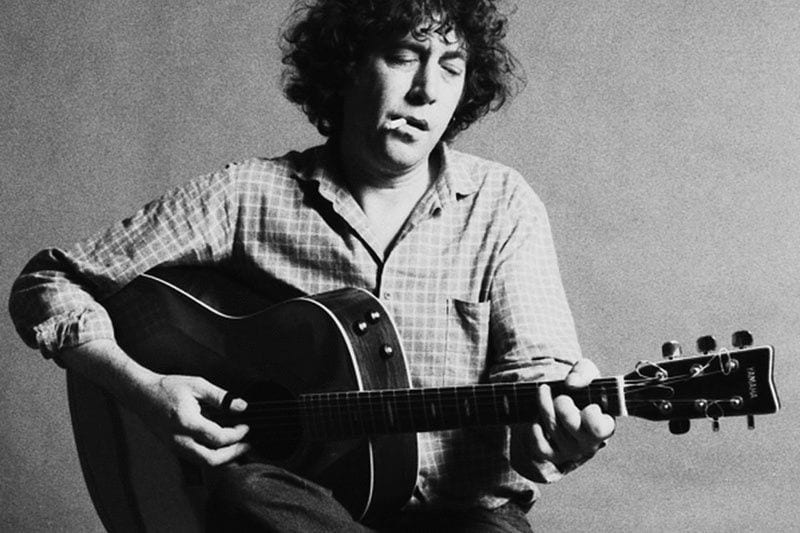

Electric Eden, Rob Young calls 1965 “the beginning of a new epoch for the new breed of singer-songwriters in Britain” because of the important collection of albums released during that year. Eponymous debuts by Martin Carthy, John Renbourn, and Jackson C. Frank all appeared, along with Shirley Collins and Davey Graham’s highly influential Folk Roots, New Roots, Mick Softley’s Songs for Swingin’ Survivors, and important releases by Donovan. Among these now legendary performers, Young identifies the “fastest-rising star of them all” as Bert Jansch, who released his debut, self-titled record in April of that year along with its follow-up, It Don’t Bother Me, in December, just after his 22nd birthday.

Earth Recordings is giving listeners an opportunity to immerse themselves in the early development of this immense talent, re-releasing Jansch’s first eight records in two sequential box sets,

A Man I’d Rather Be (Part I) and A Man I’d Rather Be (Part II). The first set, released on CD and vinyl in late January, collects Bert Jansch and It Don’t Bother Me along with the two records he released in 1966, Jack Orion and Bert and John, his collaboration with John Renbourn released just before the two joined Jaqui McShee, Danny Thompson, and Terry Cox to form the highly successful Pentangle.

The second anthology, which will appear at the end of February, presents the four solo albums Jansch produced during that band’s primary recording period:

Nicola (1967), Birthday Blues (1969), Rosemary Lane (1971), and Moonshine (1973). Taken together, the collections offer a fascinating catalog of Jansch’s artistic growth, from his early, spare and pristine musicianship through his embrace of the recording studio and its sonic potentials in symphonic accompaniment.

Jansch in his early 20s was inspired in equal measure by the American Brownie McGhee’s finger-picking blues and by British contemporary Davy Graham’s percussive, African and Eastern-influenced playing. Closely studying Graham’s famous DADGAD guitar tuning, Jansch’s version of “Anji” outshone Graham’s original and became the common standard (which Paul Simon would appropriate for Simon and Garfunkel’s 1966 breakthrough album

Sounds of Silence). Other standouts from that seminal first album include the even more eye-opening instrumental “Smokey River”, the sauntering “Strollin’ Down the Highway”, and the harrowing tale of overdose “Needle of Death”.

This album’s influence upon the development not just of British folk but rock as well cannot be understated (testimonials to that fact spanning the 1960s to the ’90s abound from artists like Jimmy Page, Neil Young, Johnny Marr, and Graham Coxon). Its follow-up, released barely seven months later, is equally masterful.

It Don’t Bother Me is, perhaps, more English inflected than its predecessor with Jansch showcasing his dexterity on “The Circle” and his delicacy on “Tinker’s Blues.” “My Lover” remains one of Jansch’s best songs, while the political “Anti-Apartheid” shows Jansch’s promise as a topical songwriter, had he chosen to follow that path further.

These early albums, even as they are dominated by acoustic instrumentation, demonstrate Jansch’s artistic restlessness. For

Jack Orion, he chose to explore a collection of covers from the English folk tradition, highlighted by the groundbreaking, ten-minute version of the title cut, which he would develop into, arguably, one of the first “folk rock” recordings with Pentangle. The album also contains his version of Ewan MacColl’s “First Time Ever I Saw Your Face”, which would become a standard in the repertoire of the era’s folk singers (and an international pop hit for Roberta Flack in 1972). From the opening cut of Bert and John, “East Wind” with its abrupt, flamenco-inflected opening and the way that the duo’s guitar lines intersect and weave in patterns like delicate lace, it is apparent that we are hearing two masters at the top of their game. Their radical for its time, the take on Charles Mingus’ “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” still sounds fresh and can surprise new listeners 50 years on from its release.

It’s easy to overlook the expressiveness of Jansch’s singing on these records. First off, of course, his guitar playing received top billing in the word of mouth notoriety that these albums gained upon release. Secondly, Jansch doesn’t put on affectations in his singing, gruffly talk-singing at times in such a way that he could be accused of barely trying, but in utilizing his natural voice, he inhabits the songs timelessly. Whether singing his compositions or covers from the classic British folk tradition Jansch’s voice is ageless, an organic, often understated accompaniment to the music itself. On a song like “Jack Orion”, his voice is a sound with the abrading power of wind bending itself around obstructions. Shutter the windows and bar the door; he still finds a way inside you.

A Man I’d Rather Be (Part II) collects Jansch’s next four records, which demonstrated more variation and for some, less consistency. Jansch’s experience in the collaborative environment of Pentangle influenced his arrangements of the songs on his fifth release, Nicola, with symphonic elements added to many of the tracks, from the full-on orchestral backing heard on “Woe Is Love, My Dear”, to the more medieval chamber arrangement on the title cut and even adding electric guitar and rock drums on “A Little Sweet Sunshine.” While some at the time considered the added elements overly intrusive, time has been kinder to these cuts, which can be seen as presaging the kind of arrangements Joe Boyd was cloaking Nick Drake’s first two albums in only a few years later. Birthday Blues finds Jansch more comfortable in his collaborations, using Pentangle’s rhythm section and Shel Talmy’s production to rocking effect on some cuts while still forging his own space, as on the haunting “The Bright New Year.”

Rosemary Lane, recorded as things were winding down with Pentangle is a step back to sparse simplicity. A balanced collection of covers and originals with his intricate guitar picking again at the forefront, it was a popular album among fans but one that critics of the time saw as a step backward. Maybe reflecting the exhaustion that was afflicting all the members of Pentangle at the time, this is a highly melancholy collection; more than any of the others, this is a rainy day record. The final album of the second anthology, Moonshine, finds Jansch revitalized, arguably outplaying his bandmates on a collection of upbeat songs. Certainly, Jansch’s singing is more open and, even, aggressive than on its predecessor.

The eight albums collected on the two anthologies are offered as originally released with no extras, and this makes the collection especially effective for new fans discovering this extraordinary work. Sometimes, the desire to “add value” by tacking on extensive alternate takes or tracks the artist had chosen to leave unreleased is counterproductive, blurring the impact of the original artistic statement. It’s a problem on the recent re-release of Pentangle’s original six records. Here, the lack of clutter amplifies the effectiveness of the originals. Particularly in light of the current vinyl resurgence, offering these albums free from extraneous tracks allows new listeners to experience the work as Jansch himself intended.