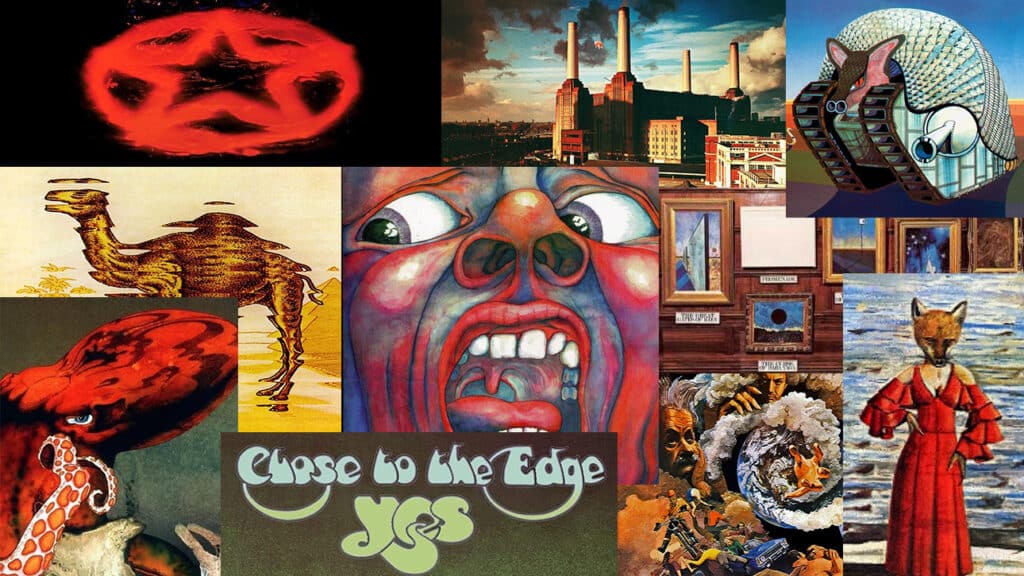

90. Rick Wakeman: “Catherine of Aragon” (The Six Wives of Henry VIII)

Rick Wakeman looms large as a progressive rock deity, providing memorable keyboard handiwork throughout the 1970s for Yes. But as more than a few people know, he was also busy with other projects. His solo efforts at once validate his status as a progressive rock monster and provide plenty of ammunition for haters who, taking one look at the album titles, would dismiss him as a monstrosity. As much or more than later works, Journey to the Centre of the Earth and (take a deep breath) The Myths and Legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, his arrangements on The Six Wives of Henry VIII are an ideal vehicle for his seemingly unlimited range and, yes, ambition.

89. Rush: “Xanadu” (A Farewell to Kings)

After three albums the band itself would declare full of hits and misses, everything came together during the recording of 2112. After that, Rush did the most progressive rock thing possible: upping the ante and doubling down on the determination. Using the all but requisite literary reference as a point of departure, lyricist Neal Peart did not half-step, selecting “Kubla Khan”, a poem by Romantic heavyweight Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Whether or not old Samuel spun in his grave or headbanged in approval, “Xanadu” gets full marks for concept and execution.

Adore or abhor them, Lifeson, Lee, and Peart are among the better players in all prog-dom (Lifeson’s extended solo during the song’s climax features some of his all-time guitar heroics). While they were gradually getting away from side-long marathons and easing into more straightforward snippets of song, in 1977 they were somewhere in the middle, stretching out with confidence but also expressing maximum feeling with something that could almost be called moderation.

88. Traffic: “Roll Right Stones” (Shoot Out at the Fantasy Factory)

If their earlier stuff was, by turns, more folk and jazz-oriented, in the early to mid-1970s Traffic were incorporating multiple elements and idioms and crafting something decidedly prog-like, albeit funky as all get out. Singer, multi-instrumentalist, and creative dynamo Steve Winwood was on a hell of a run by the time Shoot Out at the Fantasy Factory dropped; if this one gets less love and wasn’t as radio-friendly as the previous efforts, there’s a darker, at times deeper vibe in effect. Piano, organs, sax, flute, and those vocals: this is the soundtrack for a trip that need not be augmented with drugs or lava lamps; Traffic was always more substantial than any simple reduction, and they never pushed the boundaries of what was possible quite like this.

87. Pink Floyd: “The Great Gig in the Sky” (The The Dark Side of the Moon)

It wasn’t so much that Pink Floyd “got” prog better than other bands, in part because everyone on the scene was making it up as they went along. Rather, they were the outfit that, arguably, used the idiom to its fullest effect, showcasing musicianship and experimentation with (increasingly) mature and, yes, universal themes. For The The Dark Side of the Moon, the Alpha and Omega of concept albums, Roger Waters & Co. explored the pressures of modern, mechanized life and the devastating effects it has on us all, especially the ones “hanging on in quiet desperation”.

The title here, like those of the other songs, makes it clear what the song is “about”. However, using no vocals, only the off-the-cuff caterwauling of Clare Torry, the most deliberate prog band (possibly excepting King Crimson) embraced improvisation, and between Rick Wright’s mournful keyboards, David Gilmour’s solemn slide guitar and the aforementioned Torry, this track goes somewhat beyond its already ambitious subject matter.

86. The Alan Parsons Project: “I Robot” (I Robot)

Already a minor prog legend for his involvement as an engineer on The Dark Side of the Moon, Parsons went on to make significant contributions to prog-rock before becoming somewhat of a household name in the early 1980s. I Robot, like the album that preceded and followed, might be classified as “thinking man’s prog” or prog that moved keyboard-propelled formulas into territory that, while borrowing a little from Brian Eno and Kraftwerk, also anticipated the synth-laden music that would dominate the next decade. Like Eno, the Alan Parsons Project proved that one could be both meticulous and curious, and like his most lauded and disparaged compatriots, Parsons was unabashed about being intelligent, driven, and willing to take risks, all in the service of art that took its audience as seriously as it took itself.

85. King Crimson: “Larks’ Tongues in Aspic, Pt. 2” (Larks’ Tongues in Aspic)

At times cerebral, others sullen, always extraordinarily sensitive, make no mistake, Robert Fripp could throw down and wail with the aggression of a caged honey badger. On an astonishing album that contains a bit of everything, for the final number the band follows Fripp’s lead into the abyss. Like the best Crimson, there are moments where the tension threatens to overwhelm and absorb everything, and then, there’s release; here, courtesy of David Cross’s surreal violin stylings.

Anticipating grunge, there’s a feel here that shifts from far-East to outer space, but with Bill Bruford and John Wetton (barely) keeping the back end stable enough to avoid lift-off, this is a roller-coaster of wrath and control.

84. Yes: “Roundabout” (Fragile)

This song almost single-handedly ensures that even the most intractable cynics can’t dismiss everything about progressive rock. A musical marvel, it is by turns self-assured and over-the-top, and it has an almost sing-along appeal (even if no one joining in has any idea, as ever, what the hell Jon Anderson is on about). Interestingly, this is likely the gateway drug for neophytes who quickly and wisely head for murkier waters, “Roundabout” remains almost impossibly fresh and unsullied, even after decades of radio overplay. Courtesy of Rick Wakeman and Steve Howe, the song sounds at one moment like something from medieval times and the next like robots getting electrocuted. Special mention for Bill Bruford who somehow managed to be the busiest, most unorthodox, and most inventive drummer in rock.

83. Genesis: “Return of the Giant Hogweed” (Nursery Cryme)

God bless Peter Gabriel. Appearing on stage dressed like a flower, or a fox, or with a faux-hawk, he had brilliance to burn. Still a tad rough around the edges, Gabriel’s earliest work with Genesis mixes heady ambition with elements of rock’s most admired iconoclasts: there are pieces of T-Rex, David Bowie, and Roky Erickson in his approach, but the entirety of his artistic personas is utterly unique.

This song, about a giant hogweed only hints at how wonderfully weird Gabriel was before he became Peter Gabriel. What is generally — and unforgivably — overlooked is how incredible this band was all through the early 1970s. The song bristles with anger and energy, and while the atmosphere is unquestionably of its time, everyone seems (and sounds) dead earnest.

82. Egg: “Long Piece No. 3” (The Polite Force)

A delight for those who find even the most anarchic time signatures in progressive rock too conventional, and who like a side of keyboard with their keyboards. This is another one that more or less sums up all extremes of all-things-prog: indulgent, interminable, incredible. Perhaps not the ideal point of entry (the shorter pieces, particularly the better known “A Visit to Newport Hospital”, might be safer sledding), this at times seems like the band asked “You know that organ solo from “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida”? That was too short,” and at other times, it wouldn’t sound out of place on a Mahavishnu or Weather Report album.

81. Emerson, Lake & Palmer: “The Endless Enigma” (Trilogy)

One way of looking at the complicated case of ELP: easily distracted, or thrown off-course because they had too many ideas and were too talented to do anything the easy or easily predictable way, they turned into a home run hitter who strikes out too much. But when they got hold of one, there was no doubt. This, which on earlier (or, amusingly, later) albums might have been unwisely stretched into a side-long suite, is, at just over ten minutes, a convincing and even economical mini-epic. Never willing or able to do half-measures, there’s a discernible beginning, middle, and end here, and it combines the usual audacity (I mean, “The Endless Enigma”?) with a sort of hero’s quest narrative scope, in miniature (the first time the word “miniature” has ever appeared in any consideration of anything by ELP). And, in the end, it’s always all, and only, about the music. Here, the lads are locked in and letting their boundless proficiency do the talking.