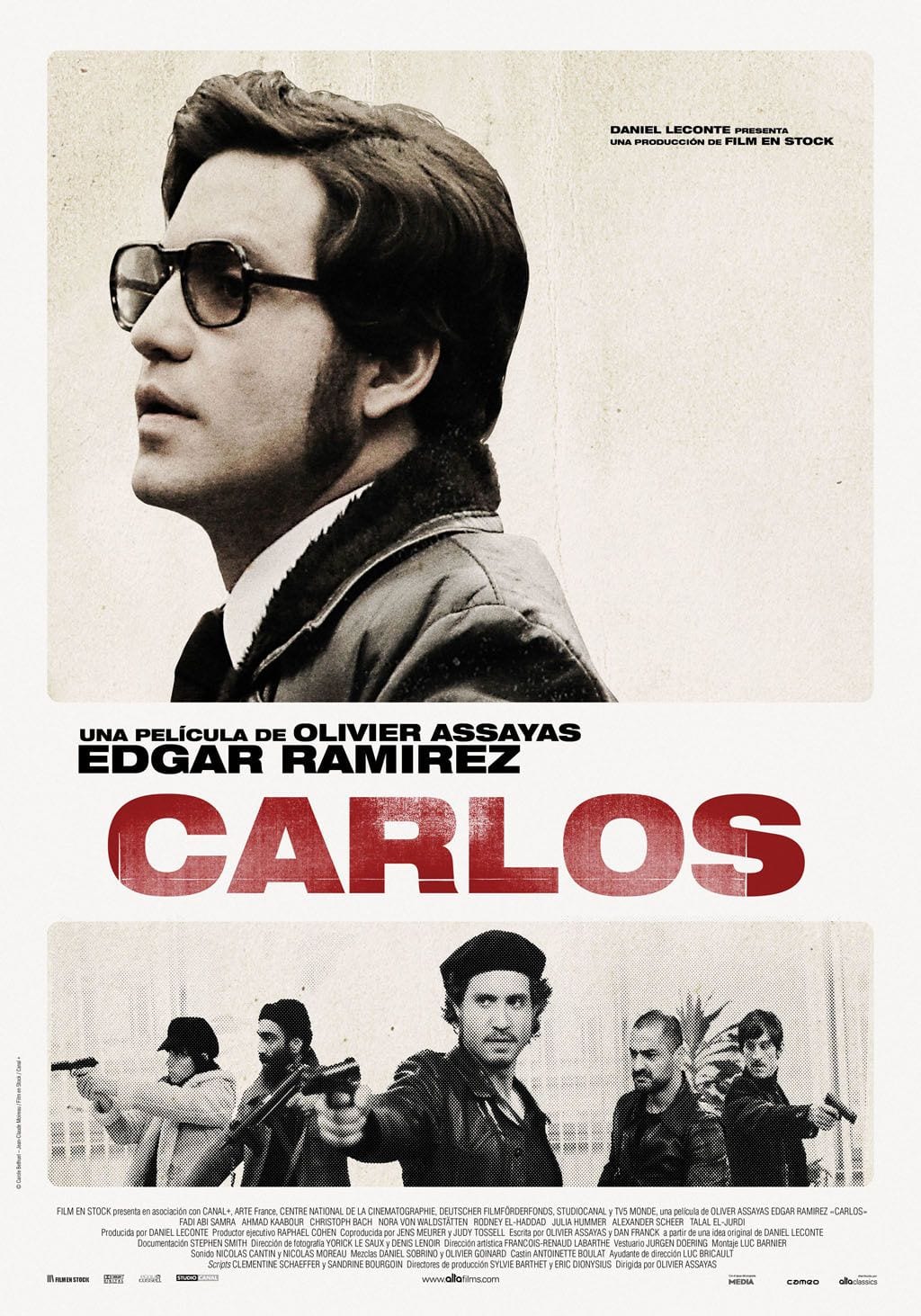

35. Carlos [Director: Olivier Assayas]

Olivier Assayas’ near-epic Carlos boasts the tagline, “The man who hijacked the world.” That man was the Venezuelan Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, who in an act of revolutionary bravado rechristened himself “Carlos” — a single name meant to echo and intimidate. In the early 1970s, Carlos become virtually a household name, the Cher or Madonna of international terrorism. As Carlos, Edgar Ramirez here commands the screen, but the film equally evokes a world of insurrectionist zeal, a particular time in history when a man like Carlos could imagine himself not just a revolutionary, but a worldwide celebrity.

From the opening, Carlos turns into a rush of international plotting, revolutionary speechifying, and guerrilla war-making. Geography blurs, from sun-bleached Yemen to sun-bleached Morocco. Insurrectionist groups flower and pass. Relishing his position at the center of it all is Carlos. Soon adopting a Che Guevara look, he is all sex and violence; his potency is purely destructive. In an early scene he admires himself wet and naked in the mirror as the television news recounts his latest bombing. Later, while using a grenade to seduce a fellow revolutionary, Carlos says, “Weapons are an extension of my body.” He pursues satisfaction for both his weapons and his body. – Jesse Hicks

34. Alice in Wonderland [Director: Tim Burton]

Tim Burton’s vaunted re-imagining of Lewis Carroll’s classic tales of fantastic dream-logic features a nubile young-adult Alice (Mia Wasikowska) enmeshed in a heroic quest narrative in a strife-torn Wonderland. That the resulting film is considerably more than a mere capitulation to Hollywood demographic schemes and recycled Joseph Campbell archetypes can be put down to the glorious visual flourishes and ingeniously idiosyncratic designs of Burton and his team, as well as the wonderfully performers camping it up in this technicolor realm. Helena-Bonham Carter’s Red Queen, with her CGI-inflated head and petulant selfishness, is a joy in every one of her scenes, and Johnny Depp adds the Mad Hatter to his gallery of sensitive, eccentrically-mannered leftfield rogues. As beautifully-constructed eye candy cinema goes, the multiplex crowd could do far worse than Alice in Wonderland. – Ross Langager

33. Casino Jack and the United State of Money [Director: Alex Gibney]

Jack Abramoff is famous for making money. He made lots of it, he made it for a long time, and he made it illegally. He didn’t make it alone, though. And the way he made it was not his own invention. This is the argument made by Casino Jack and the United State of Money: the erstwhile super-lobbyist Abramoff is surely audacious and noisy and “a man of many hats,” but he is also a little mundane, not so singular or deviant as he’s been made out to be.

The reasons for calling him extraordinary are obvious enough: if Abramoff’s schemes to buy and sell members of Congress were his own alone, and he’s now imprisoned for his crimes, the problem appears to be resolved. But even the most naïve observer knows this can’t be true, and now it seems that everyone, from Tea Partiers to Coffee Partiers, is wary of Congress as a matter of course. So, when, just a couple of minutes in, Casino Jack asks its first and most pressing question — “Is this the story of individual corruption or the story of what our democracy has become?” — you already have an idea of the answer. Still, coming to the answer is a fascinating process.

Like Alex Gibney’s other documentaries, it begins with a violent crime, in this case, the 2005 gangster-style murder of SunCruz founder Gus Boulis. The plot thickens, as it were, as the film digs into the background of this purchase, specifically, how Abramoff came to be rich enough to make it. Significantly, Abramoff does not take part in telling his story, at least on screen. And in the face of this problem, the film finds a series of ingenious solutions — elegant, funny, and preposterous ways to sort out the man’s thinking and contexts. – Cynthia Fuchs

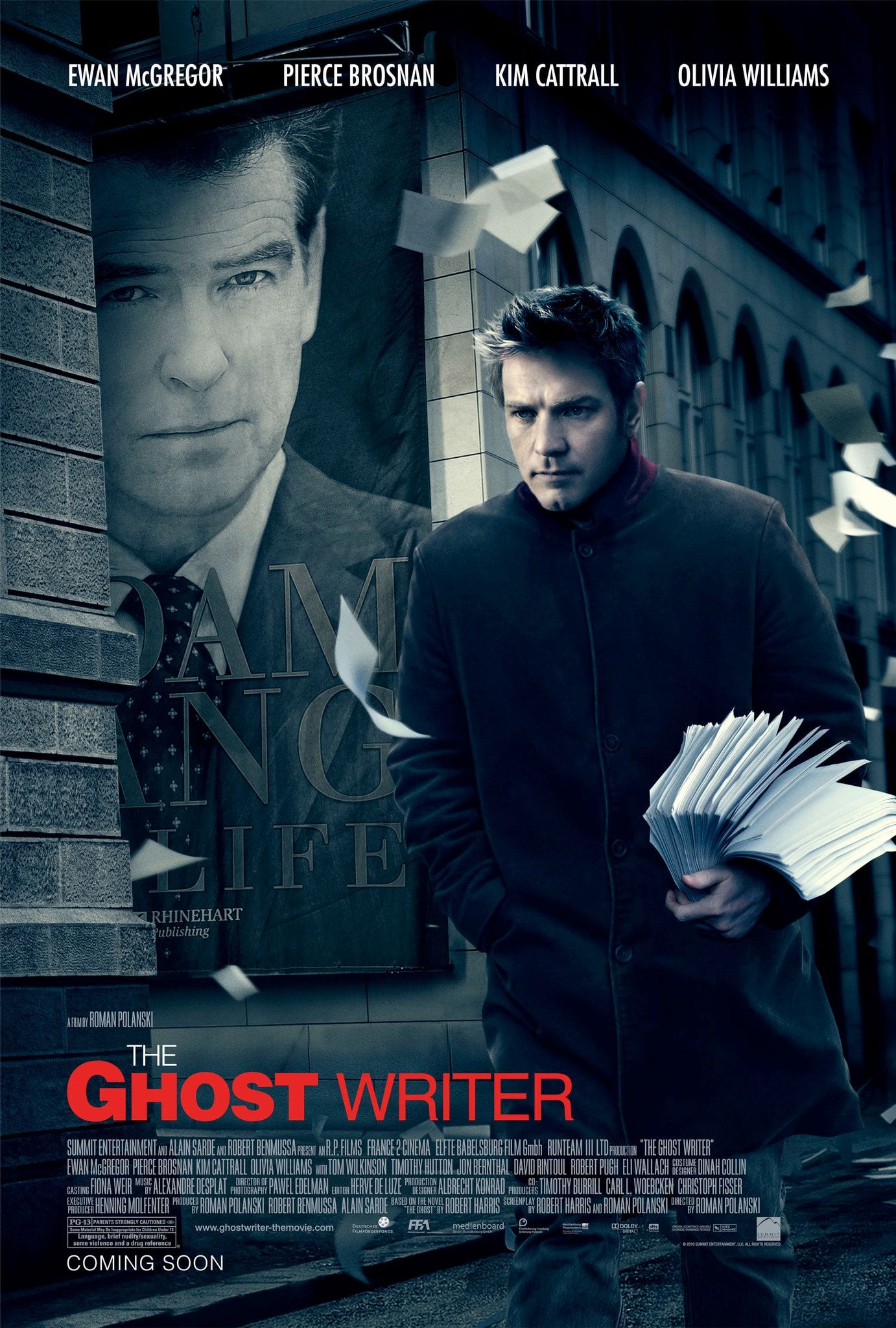

32. The Ghost Writer [Director: Roman Polanski]

In Britain it’s just called The Ghost, which better expresses the multiple meanings present in Roman Polanski’s political thriller about an unnamed writer (Ewan McGregor) offered too much money to prepare the memoirs of a British Prime Minister (Pierce Brosnan) whose similarities to Tony Blair are impossible to miss. The ghost of the previous writer, who came to an unfortunate end, hovers over the story, the writing takes place in an isolated beach house, the sky always seems to be overcast… and I’d hate to spoil the fun by saying more. Based a Robert Harris novel, The Ghost Writer is also a pointed political satire and the end result is a film which works on multiple levels at once. – Sarah Boslaugh

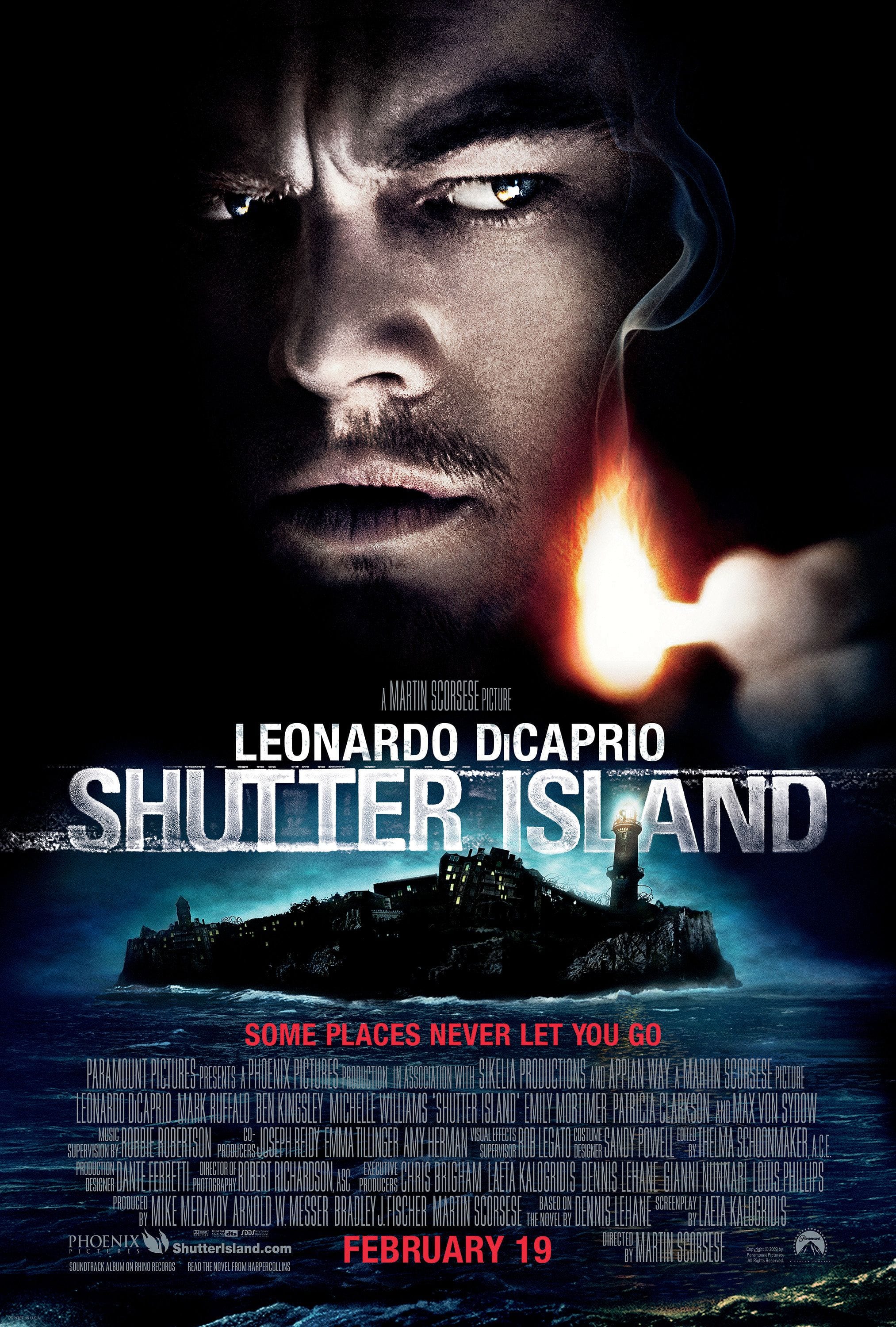

31. Shutter Island [Director: Martin Scorsese]

For anyone who wondered if Martin Scorsese had lost his flair for old fashioned filmmaking, this evocative noir-esque thriller was proof of his continuing gifts. Sure, the performances were electrifying and the narrative a twisted knot of red herrings and last act surprises, but the real star here was the American auteur. He took his love for all things Hitchcock, married them to a postmodern idea of dread, and turned it all into a sinister stew pot of visual finesse and narrative terror. Even in today’s contemptuous, couldn’t care less world, Scorsese got audiences curious, and questioning, wondering if what they saw was reality or the unhinged images of a deranged mind. By the end, it was impossible to tell, which is why this movie remains one of the year’s most compelling. – Bill Gibron

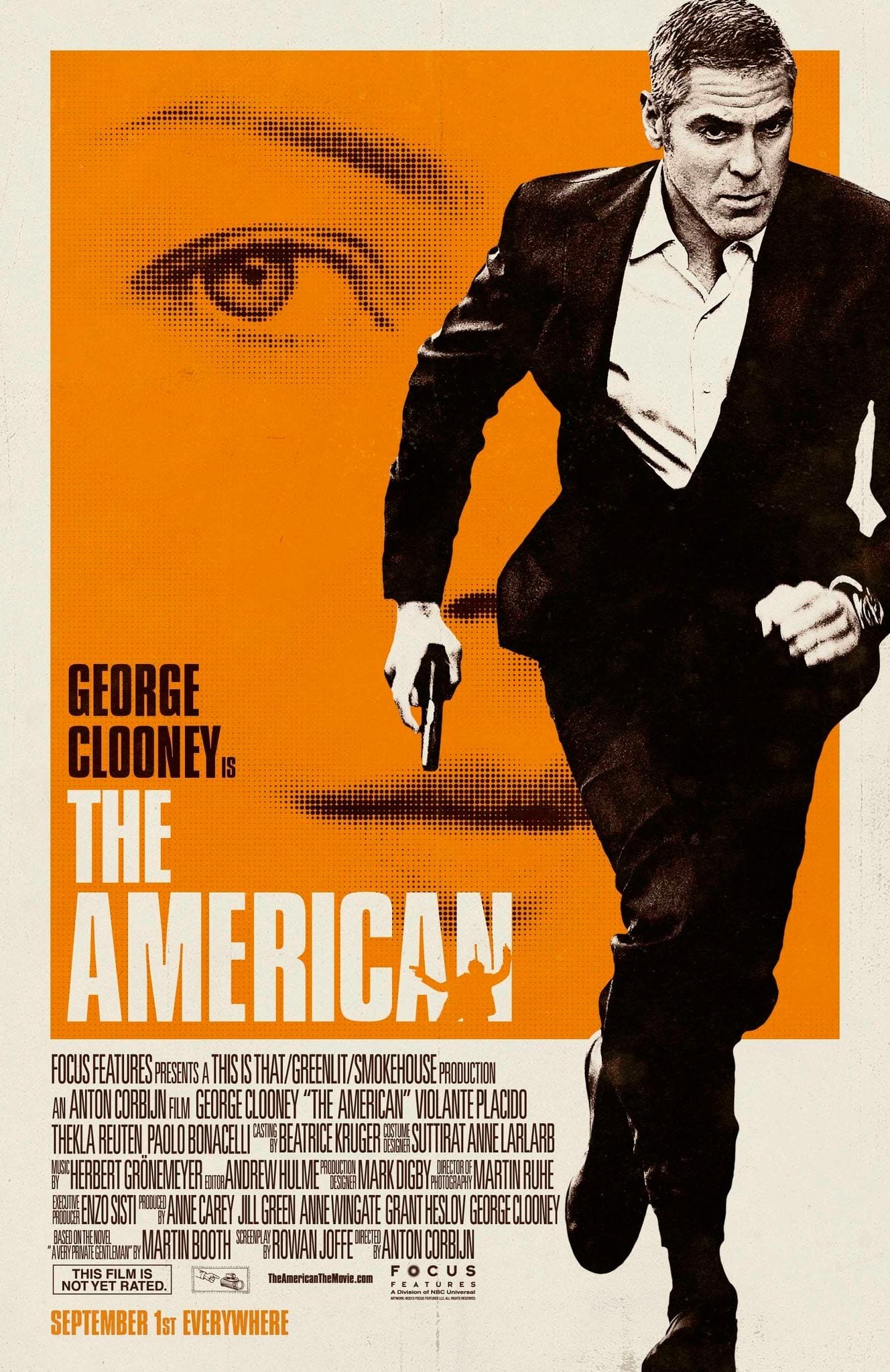

30. The American [Director: Anton Corbijn]

In Anton Corbijn’s The American, George Clooney plays Mr. Butterfly, an assassin and weapons specialist who, after complications resulting from an assignment in Sweden, relocates to the Italian countryside as he prepares for one last job. Taking more than a few cues from Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai, The American is put together with the same careful precision that Mr. Butterfly applies to his custom rifles. Featuring gorgeous photography and masterful directorial restraint by Corbijn, this overlooked gem is meditative drama of the finest order. High on atmosphere and low on histrionics, those looking for the Jason Bourne-style thriller promised by the marketing campaign were sorely disappointed; I, however, found it enthralling. – John Sciaccotta

29. Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer [Director: Alex Gibney]

Before he was Kathleen Parker’s slow-pitch partner on Parker Spitzer, Eliot Spitzer was Ashley Dupré’s client, a.k.a., the Luv Gov. And before that, he was New York’s spectacularly hard-hitting attorney general. And while you might guess that Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer recounts these changes in fortune, it is only partly interested in Spitzer per se. Yes, the infamously self-destructive personality provides for passing intrigue, as do his insights into the financial system he meant to clean up.

But the more striking focus of Alex Gibney’s terrific documentary is more rightly that system, and how it allows big name players to win — again and again — by any means necessary. The film makes no pretense of defending the former New York governor’s deception of his wife and family, or excusing his ridiculous choice to patronize the Emperor’s Club VIP. It does, however, situate Spitzer’s bad behavior and questionable character in multiple broader contexts, all in flux by definition. Spitzer is not deviant, in this view, or even exceptional. He is, instead, a participant in a game that is at once too mundane and too creepy, one that no one seems inclined to challenge, but only to play as brutally as possible, and above all, to perform well. – Cynthia Fuchs

28. Four Lions [Director: Chris Morris]

Controversy courting satirist Chris Morris is best known in the UK for being the enigmatic host of spoof news TV shows such as Brass Eye (Channel 4, 1997) and The Day Today (BBC, 1994), so it came as little surprise that his feature-length debut would tackle the most prickly contemporary matter of fundamentalist Islam. Ripe with moments of inspired slapstick humor, and a heedless abandon towards his subject matter, Morris treads the tepid line between absurdity and moral bankruptcy with unrelenting nerve. While, his deft mis-en-scène adds an extra punch to keep the viewer hanging off the edge of the seat.

The greatest feat of Four Lions however, is its ability to psychologise the inanity of modern terrorism. As the picture unfolds, it becomes evident that the self-defeating idiocy of such an act can only be the preserve of the dim. Subsequently, Morris concludes by reducing the seemingly unthinkable to simple matters of the human condition: i.e. pride, peer pressure, and a need for a sense of purpose. Speaking of the film during its initial release, Morris noted that he hoped the film would do for Islamic terrorism what classic BBC TV show, Dad’s Army, did for the Nazis, i.e. show them as scary, but ridiculous. Morris, on this occasion, has succeeded. – Omar Kholeif

27. Greenberg [Director: Noah Baumbach]

Noah Baumbach has shown endless fascination with men who have a rough time growing up and settling into society’s expectations — guys (and ladies, but especially guys) who are almost cripplingly self-conscious about the possibility that they may be too smart, or neurotic, or self-conscious, for their own good. In Greenberg, he checks in with one such guy at forty, played with fearless humor and abrasiveness by Ben Stiller. “I’m weirdly on tonight,” he observes after complaining about missed birthday calls and ripping into restaurant-goers for laughing and clapping (“laughter already demonstrates appreciation”) — privately, of course.

When Greenberg meets Florence, a sweet doormat of a 20-something played by Greta Gerwig, Baumbach doesn’t pull any punches; this isn’t a rom-com about a grumpy guy learning to love. But for all of the bile and discomfort (both often hilarious), the movie doesn’t quite despair, and arrives at Baumbach’s most perfect ending since his masterpiece Kicking and Screaming. – Jesse Hassenger

26. The Tillman Story [Director: Amir Bar-Lev]

By all accounts Pat Tillman, who left a career in the NFL to enlist in the U.S. Army, was a good soldier but also an independent thinker whose choice of reading material included both Noam Chomsky and the Bible. When Tillman was killed in Afghanistan the U.S. military tried to capitalize on his celebrity status, producing two entirely false stories about the circumstances of his death. His family’s refusal to play their part in this scripted drama eventually led to the truth being revealed: Tillman was killed by friendly fire. Director Amir Bar-Lev’s film presents a Pat Tillman who is far more complex and interesting than the Army’s made-up version while his family’s simple insistence on learning the truth shames the military PR machine which sought to use Tillman as a recruiting tool. – Sarah Boslaugh

25. Please Give [Director: Nicole Holofcener]

There are precious few film directors working right now that consistently capture such a diverse array of femininity as Nicole Holofcener — the director of such films as Walking and Talking (1996), Lovely and Amazing (2002), and Friends with Money (2006). Alejandro González Iñárritu comes to mind, as does Woody Allen, but to be more concise, there are no female film directors making movies about women with the scope that Holofcener favors once again on the low-key, yet completely enthralling Please Give.

The film is an ode to ignorant goodwill, cheating, greed, cynicism, and purity that is equally hilarious, sharp, awkward, and heart-breaking. Written with gusto, Holofcener’s female characters — played by Ann Morgan Guilbert, Rebecca Hall, Catherine Keener, Amanda Peet, Lois Smith, and Sarah Steele — again encompass many ages, shapes, and philosophies and the clashing of these strong, individual women as they cross paths provides for a fascinating viewing experience full of brains, guts, and wit.

This is Holofcener’s best film to date, and she just keeps on getting better at portraying an intriguing range of unique women’s experiences for the screen. – Matt Mazur

24. Easy A [Director: Will Gluck]

How refreshing it is to see a smart, teenaged, female film protagonist talk like a smart, teenaged female. Easy A‘s Olive, portrayed lovingly by Emma Stone, doesn’t use texting terms or slang when she’s speaking. She isn’t dim, ditzy, or klutzy — nor is she uptight or anal-retentive. She grapples with real issues of sexuality and social perception. And, though the process is full of awkwardness and poor decision-making, she’s all the more likable for the smart way she goes about attacking these issues. (If only her male counterparts were as well-drawn and sharp, but we can’t have everything.) We’d say that filmmakers should take note of films like Easy A and Mean Girls and create more female-centered teen comedies with characters as smart and fully realized as the ones in those films — but, really, all romantic comedies would do well to follow Easy A‘s lead. – Marisa LaScala

23. I Love You Phillip Morris [Director: Glenn Ficarra, John Requa]

I Love You, Phillip Morris is another one of those strange-but-true tales: Con man Steven Russell (Jim Carrey), a happily married family man, is hit with a car, decides to come out as gay man, turns to conning people to afford his lifestyle, gets caught and sent to prison, falls in love with another prisoner (Phillip Morris, played by Ewan McGregor), and spends the rest of his life in prison, breaking out of prison, and breaking Morris out of prison so the two can be together. (Phew!)

While the facts of the story speak for themselves, the tricky part is the tone needed to balance out all of the narrative’s wackiness — and directors Glenn Ficarra and John Requa, together with Carrey, succeed in finding the perfect one. It acknowledges Russell’s strangeness without delighting in his misdeeds. It recognizes the humor inherent in Morris’ cons, but still manages to wring out lots of deep emotion when it is called for. When the film ends, you admire Russell — but you also kind of want to hit him in the face if you ever get a chance. – Marisa LaScala

22. Cyrus [Director: Jay Duplass, Mark Duplass]

The most consistently hilarious film yet from Mark and Jay Duplass (The Puffy Chair, Baghead) often had laughs so loud at the film festival screening where I caught it that dialogue was missed. Jonah Hill plays Cyrus, the adult son of Molly (Marisa Tomei) who slowly drives a wedge into her burgeoning relationship with John (John C. Reilly). The audience is kept guessing for most of the film on what exactly is going on with Cyrus: whether he’s mentally challenged, a psychopath with a Norman Bates streak or just a normal if slightly insecure guy. I’m glad to see the Duplass brothers get to work with this kind of a budget, with a studio and a real distribution deal, coming out with a product that has a slightly slicker look so that people other than shabby ‘mumblecore’ fans like myself can finally see and appreciate their brilliance as well. – Jenn Misko

21. Let Me In [Director: Matt Reeves]

Let Me In had an uphill climb ahead of it from its very inception. It’s a remake of a Swedish film that was hugely popular with film geeks, so the internet was against it. Director Matt Reeves’ previous film was Cloverfield, a movie so stylized and alternately loved and hated that it was impossible to get a read on his directing ability. But the casting of Chloe Moretz (Kick-Ass) and Kodi Smit-McPhee (The Road) as the two pre-teen leads in the movie was a positive sign. In the end, general audiences rejected the movie, but most of those who took the time to watch it loved it. Smit-McPhee and Moretz are indeed excellent as the shy, abused kid and the young-looking vampire who moves in next door.

If the original Let the Right One In had a problem, it was its languid pacing. Let Me In tightens the pacing without losing the slow, chilly atmosphere that made the original such a departure from most modern horror. This is the sort of horror movie that has more on its mind than just scaring you, and its compelling story and strong performances makes it worth watching, even for hardcore fans of the original. – Chris Conaton

20. Rabbit Hole [Director: John Cameron Mitchell]

There are an awful lot of indie movies about grieving families starring an awful lot of talented actors fishing for awards-season attention. For the key to what makes Rabbit Hole stand apart, simply observe Nicole Kidman’s face. She’s received some attention in recent years for china-doll immobility, but playing Becca, a suburban mother who hast lost her four-year-old son, lines reappear and lovely cracks begin to form. When she regards her husband Howie (Aaron Eckhart), waves of complex feelings — affection, resentment, patience, anger — ebb and flow across Kidman’s face with beautiful subtlety. John Cameron Mitchell’s attentive but unfussy direction and playwright David Lindsay-Abaire’s script provide strong material, yet it’s Kidman and Eckhart, the good-looking movie stars, who make the whole thing feel so honest. – Jesse Hassenger

19. Blue Valentine [Director: Derek Cianfrance]

This funny valentine has been described and praised by many usually cool and detached critics for being “raw” — and certainly the emotions depicted in Blue Valentine are rough-hewn — but I would argue that Derek Cianfrance’s achingly melancholic film, in terms of construction, is the the opposite of “raw” in every way. Thoroughly refined imagery is lovingly strung together to thoughtfully examines the relationship struggles of Dean and Cindy, a simple premise, maybe, but it’s one that soars in unforgettably cinematic ways.

Cianfrance, who studied with renowned experimental filmmakers Stan Brakhage and Phil Solomon, shows loving attention to every aspect of the film, from the searing, modern performances from stars Ryan Gosling and Michelle Williams, to the poetic use of both natural and artificial light and subtle digetic sounds, to of course, the taut dialogue. If ever there was a cinematic equivalent to the music of Patti Smith, it would be very much like Blue Valentine: a bit punk, a bit cocky, a bit obvious, a bit too scary, but always a moving, gripping artistic expression. – Matt Mazur

18. Fish Tank [Director: Andrea Arnold]

In the tall, washed-out grey ranges of council-flat towers somewhere in a banged-up northern England town, a single mother shares a few rooms with the two borderline-feral girls she is theoretically raising. Mia is the older of the pair, stalking the concrete wasteland looking for a fight or something (family?) that she can’t put a name to. The younger, Tyler, is a gutter-mouthed urchin with the fierce, thoughtless courage of a woman three times her age. When a sense of succor comes, it’s in the absolute worst form — her mother’s half-wild boyfriend — and the sense of frustrated vengeance that takes over the film’s later sections has a pulsating fury but stirring humanity that echoes Dickens at his evocative best. Writer/director Andrea Arnold’s second feature is very simply the most deeply felt and deeply feeling film of the year. – Chris Barsanti

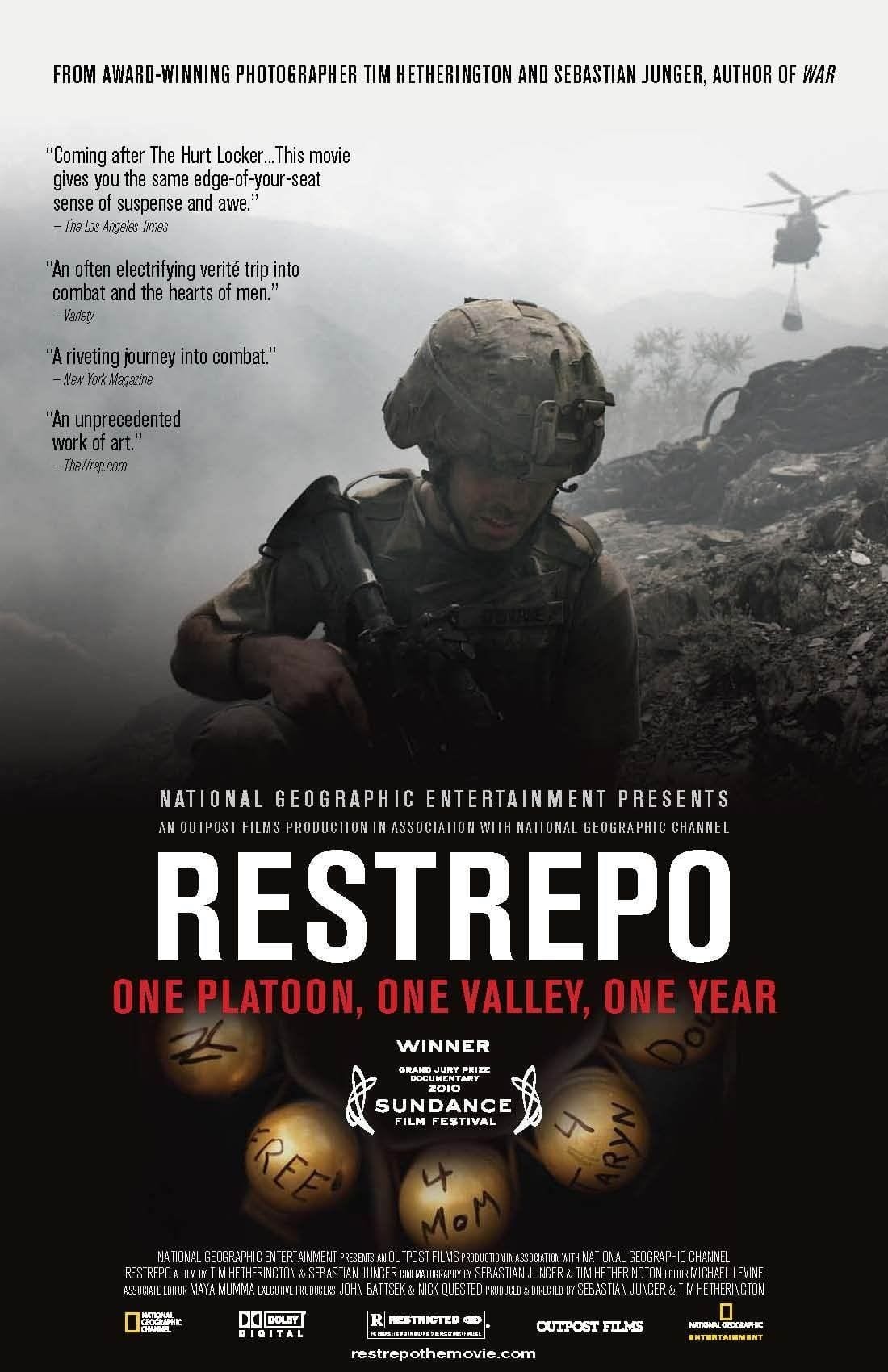

17. Restrepo [Director: Tim Hetherington, Sebastian Junger]

At the start of Restrepo, the men of Second Platoon, Battle Company, land in the Korengal Valley of eastern Afghanistan. It’s May 2007, and they’re going to be here for 15 months. Coming off the chinook, they look around — at a vast expanse of nowhere. Remembering his first impression, Sergeant Aron Hijar says, “I thought, ‘Holy shit, we’re not ready for this.'” The company’s experiences make up the entirety of this outstanding documentary, recorded by embedded filmmakers Sebastian Junger and Tim Hetherington.

Culled from some 150 hours of footage, the movie shows a range of interactions at the outpost called Restrepo, named after a company medic who is killed early during the deployment, some harrowing battlefield imagery as well as post-deployment interviews conducted in Italy. It is, as Junger says, “about soldiers and it reflects their reality and their internal dialogue.” But as discussions go forward concerning funding and policy for this very long war, the film is something else as well, of course, resulting from Junger and Hetherington’s choices, as well as the soldiers’ memories. Their very specific realities are consistently compelling and disconcerting. If their stories are not explicitly “political,” they are all profoundly subjective and persuasive: this war, like all wars, is a terrible thing.

The very immediacy of Restrepo makes this case. No matter how America’s campaign in Afghanistan is won, lost, or reframed as “history” in years to come, it is, right now, a series of events, small and large, productive and destructive. – Cynthia Fuchs

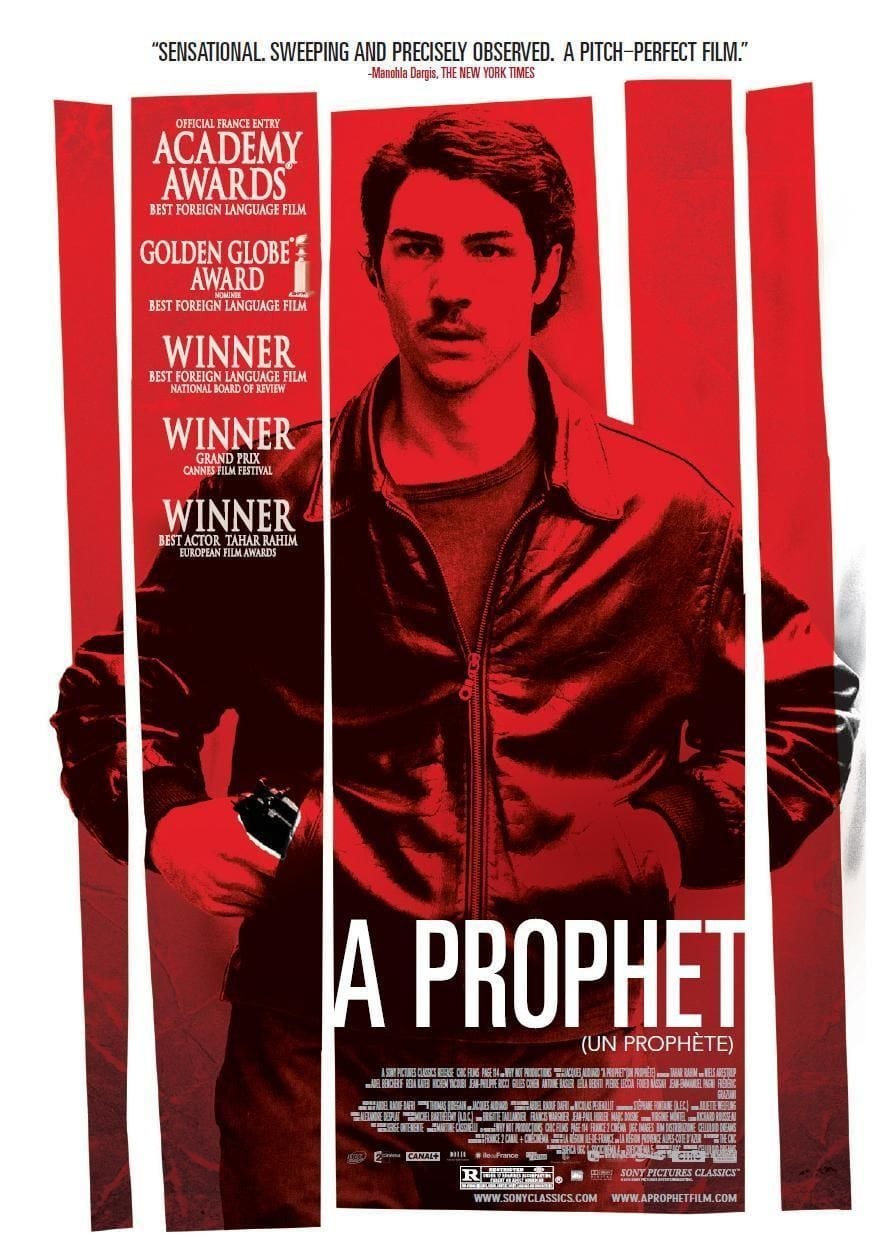

16. A Prophet [Director: Jacques Audiard]

Jacques Audiard’s mesmerizing French prison epic starts down a predictable path, but takes its young character on a journey of hard-fought survival told with an unforgettable verve and originality. The first time that we see young prisoner Malik El Djebena (the astounding Tahar Rahim) kill a man, it’s a shattering event. Planned beforehand with excruciating care, the hit goes wrong from the start and ends up a bloody fiasco, Malik’s victim spraying the cell with blood from his butchered neck. Malik can only watch, trembling with adrenalin and terror, as the man’s life shudders out of him before he can return to his own cell and try to live with himself.

Many crime narratives demand for their protagonist a chained linkage of tasks completed, rivals defeated, glories attained. While Audiard’s film is a crime story to its very core, he doesn’t appear to feel the same need as many of his fellow filmmakers to valorize his young criminal hero. Yes, A Prophet delivers many expected crime story hallmarks, particularly the satisfaction that comes from seeing a criminal enterprise being pieced together and operated with little more than a few conversations and fear. – Chris Barsanti

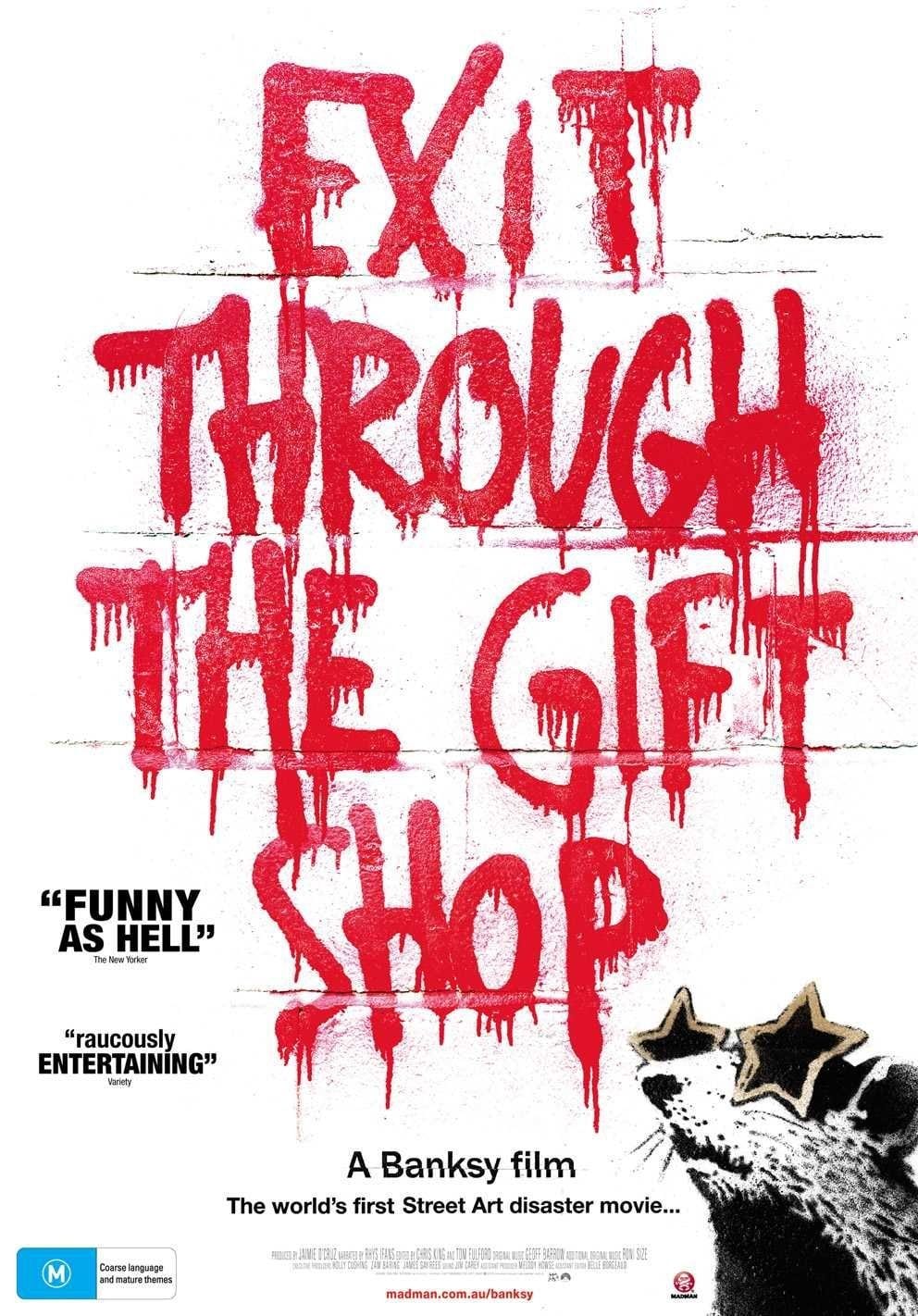

15. Exit Through the Gift Shop [Director: Banksy]

Who controls the artist’s voice? Is it the artist, maker of the product? Or does the product speak? When the art becomes a commodity, does the final word go to the highest bidder? These questions, and a flood of others, are the stuff of Exit Through the Gift Shop, a hilarious documentary directed by a mysterious prankster and celebrated street artist known worldwide only as “Banksy”.

A spiritual successor to Orson Welles’ F for Fake, Exit Through the Gift Shop purportedly aims to be an authentic street art documentary that shifts into a character study of Thierry Guetta, the gadfly/videographer responsible for most of the footage in the film. Banksy’s mid-film flip from being Guetta’s subject to his controlling voice is a clue to the film’s overall point, which is to regain control of an experiment gone awry. Street art, like Guetta’s footage and eventual artistic ambitions, has outgrown its creators, and its absurd preservation and commodification (cannily documented in the film) spells the probable death of the transitory form.

The line between fact and fiction seems fluid in Exit Through the Gift Shop, but the thesis of the film rings true regardless of (or perhaps because of) the trickery on display. Namely, who better than the artist to kill his own creation when it turns on him? – Thomas Britt

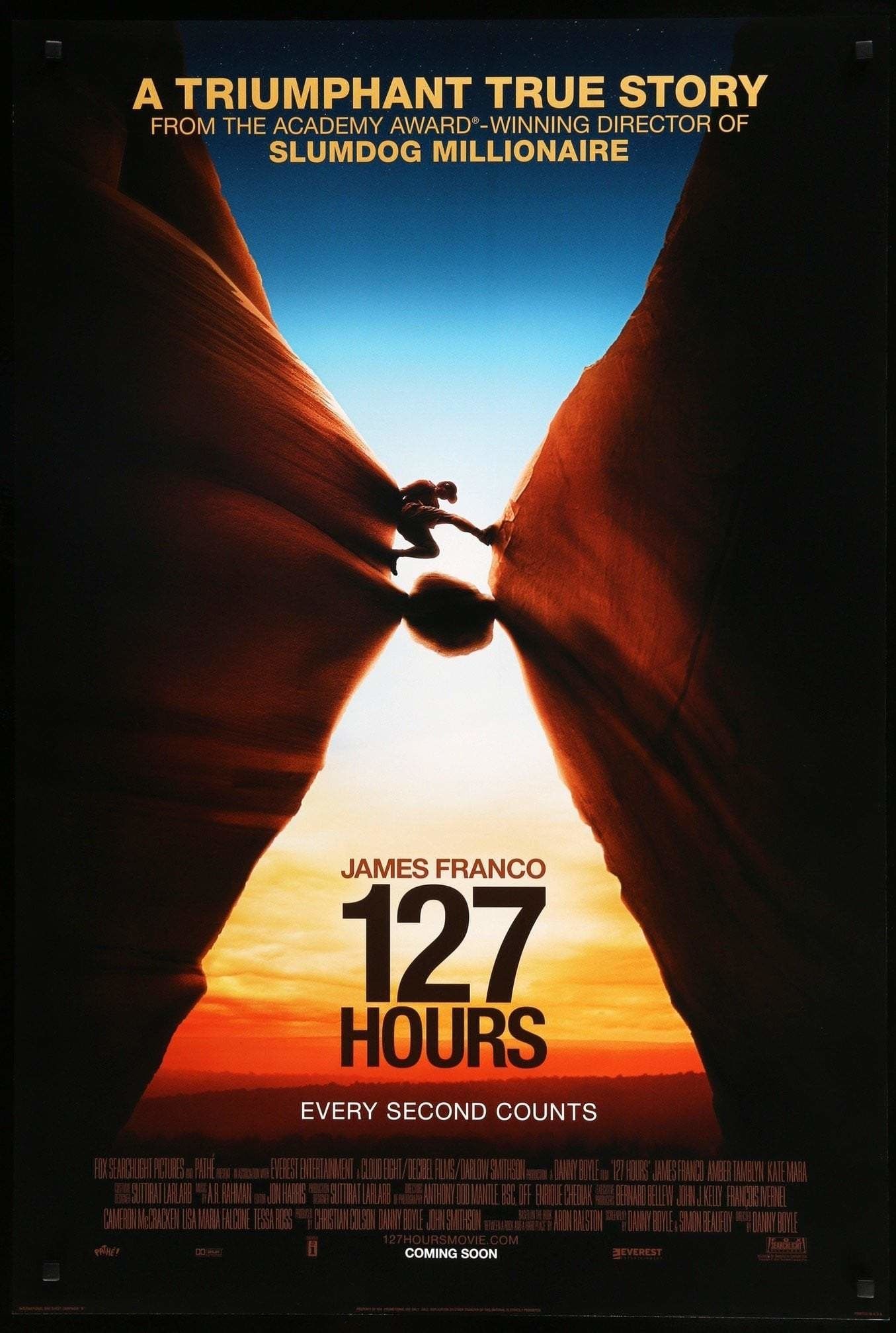

14. 127 Hours [Director: Danny Boyle]

One would be hard-pressed to come up with a film idea less cinematic than an one-man show about a character that cannot move. There are thrills to be found in the real-life survival story of Aron Ralston (played here by James Franco), a young man incapacitated on a hiking adventure in a Utah canyon. However, the stakes of Ralston’s dilemma stem mostly from a single decision: How should he free himself from being trapped by a boulder against a canyon wall?

Director Danny Boyle and ingenious cinematographers Anthony Dod Mantle and Enrique Chediak present this solitary situation, beset by tests of the body and mind, with an approach that drops the viewer into Ralston’s head. We cannot aid Ralston, but the cinematographic proximity and captivating performance by Franco give us a privileged position in his predicament. We together remember his idealized past and conceive a magically realistic future that depends on his survival. The grim details of his self-amputation are well-known and boldly executed in the film, though the movie’s most powerful and exceptional asset is its invitation to contemplate our own choices and capacity for self-determination. – Thomas Britt

13. Scott Pilgrim vs. The World [Director: Edgar Wright]

Lovesick 20-something Scott Pilgrim (Michael Cera) fancies himself a nice guy, like many of Cera’s roles, but is enough of a callous jackass to make the part something you haven’t seen from Cera before. When Scott falls for Ramona Flowers (Mary Elizabeth Winstead), he finds himself at odds with her seven evil exes, all of whom he must defeat in mortal combat. Sadly, Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World is a prime example that no matter how much advance hype there is on the internet (there was an absurd amount), and no matter how good the reviews are (they were overwhelmingly positive), film geeks alone can’t open a movie. Which is too bad because Edgar Wright’s homage to pixilated videogames and comic books is nuts, visually inventive, and entertaining as all hell. This one comes readymade for cult classic status. – Brent McKnight

12. Inside Job [Director: Charles Ferguson]

“Nothing comes without consequence,” observes Andri Magnason. The filmmaker and author is reflecting on the fate of his native Iceland, where the banks collapsed at the end of 2008, whereupon the unemployment rate tripled. These dire consequences seem clear enough, and so provide a vivid opening sequence for Inside Job. Shots of spectacular mountains and fluffy clouds give way to frames full of stats and graphs, Alcoa smelting plants and gray urban streets. But such obvious consequences are only the point of departure for Charles Ferguson’s new documentary.

This start leads to remarkably coherent, bracing, and frequently galling analysis of the recent world financial crisis, one that focuses on the (current) lack of consequences for those who caused it. Inside Job brings to this complicated, often confounding saga the same sort of intellectual and moral rigor that Ferguson’s No End in Sight brought to the Bush administration’s management of the Iraq War.

Much like the previous film, this one makes talking heads — traditionally the dullest of documentary formats — compelling and revelatory. Each interview is delivered in direct relation to another, whether complementary or contradictory, the orchestration at once engaging and horrifying. – Cynthia Fuchs

11. Toy Story 3 [Director: Lee Unkrich]

Year after year, Pixar comes through. Their streak of box office and critical hits has gone on for so long that it’s beginning to look like they will never have a true misfire. Revisiting the Toy Story franchise 11 years after Toy Story 3 seemed like a dodgy prospect, but director Lee Unkrich and the rest of Pixar once again delivered. Toy Story 3 manages to be a prison movie, a caper movie, and even resembles a horror movie at times. But at its core, it’s a movie about growing up.

The overarching plot of the toys’ owner Andy moving away to college gives the movie its soul, but the action and comedy throughout keeps the film lively. The animation on display here is subtler than recent Pixar efforts, but just as amazing. Take another look at the scene where Mr. Potato Head is stuck as a tortilla. The scene in the incinerator and the sequence with Andy and Bonnie near the end of the movie hit just as hard emotionally as any live-action film out there in 2010, and it’s why Toy Story 3 is near the top of so many Best of the Year lists, including this one. – Chris Conaton

10. Mother [Director: Bong Joon-ho]

In the latest by Korean director Bong Joon-Ho, a mother sets out to clear her mentally challenged son’s name of a murder. Even though we as an audience were afforded the privileged position of seeing what happens very early on in the film, suspense in the narrative is crafted well enough that it’s still possible to have some doubt about the truth. Starting its run at 2009 film festivals but only seeing its limited USA release in 2010, this is the kind of film I put off watching for a while because I expected it to be “difficult” in some way, but ended up regretting the wait when I took in the truly exciting cinematographic and narrative choices as well as the deeply empathetic portrayal of the mother-in-crisis by Kim Hye-ja. – Jenn Misko

9. The Kids Are All Right [Director: Lisa Cholodenko]

The Kids Are All Right feels progressive at first because it features a well-adjusted family that just happens to have a lesbian couple as the parents. What makes Lisa Cholodenko’s film feel real, though, are the domestic issues that Jules (Julianne Moore) and Nic (Annette Bening) have to sort through. Jules is the domestic artist-type who always has a not-quite-realized dream on the horizon, while doctor Nic is the family breadwinner who eases her stress by drinking too much. When their two teenage kids contact their sperm-donor father (Mark Ruffalo), and the family gets to know him, his destabilizing presence pulls the family’s issues into the open. This film could easily have descended into too-precious melodrama, but the strong cast makes it all seem very honest and believable. It’s a small story well-told. – Chris Conaton

8. Never Let Me Go [Director: Mark Romanek]

Two girls and a boy grow up in a British orphanage where nobody ever comes to choose them for adoption. Come adulthood, the three – Carey Mulligan, Andrew Garfield, and Keira Knightley – have formed a love triangle with deeply fraught tensions that arise from the suspicious nature of their upbringing. Mark Romanek’s cool-to-the-touch science-fiction tone poem (adapted sharply by Alex Garland from Kazuo Ishoguro’s novel) has a washed-out palette and sense of crumbling foreboding that captures the cruel essence of postwar British sci-fi. The tremblingly tearful acting was distracting for some, but if you accept the story’s brilliant hook of an idea (namely, the reason why are these orphaned children raised in separate facilities in this vaguely alternate universe), what comes after is a chilling, horrifically true answer to a moral quandary the human race hasn’t faced. Yet. – Chris Barsanti

7. The Fighter [Director: David O. Russell]

2010 was a year of technical bravado in film. From the laden with imagination Inception to the terrifyingly terrific Black Swan, many movies laid their claim to fame through careful craftsmanship, but, with the exception of the tear-tugging Toy Story 3, lacked emotional resonance. The Fighter makes up for every one of its peers’ slight shortcomings by providing a too-good-to-be-true true tale. Like Rocky before it, David O. Russell’s boxing drama tells the story of an underdog fighter held back by personal strife. Only in this story, Fighter Mickey Ward (Mark Wahlberg) has to unite a nine-member family wrought with dysfunction in order to reach his title fight. Though the actors are all in Oscar form (see the Best Performances list for more), Russell doesn’t set his camera down and let them do the heavy lifting. His own craftsmanship is second to none, but it’s still the heart he finds in the The Fighter that earns it the championship belt. – Ben Travers

6. Inception [Director: Christopher Nolan]

Director Christopher Nolan has spent his career toggling between big-budgeted action films and more thoughtful, cerebral fare. (Memento and Insomnia preceded Batman Begins, which was followed by The Prestige, which was then followed by The Dark Knight, and so on.) Inception is unique in that it succeeds at being both. At its core, it’s a heist movie, where a group of characters conspire to steal the most precious commodity of all: the ability to originate our own thoughts. And, like most heist movies, it comes with its own set of adrenaline-pumping action setpieces, with men with guns, car chases, big explosions, and perhaps the best fist-fight put to film this year.

But Inception is so much more than a typical crime thriller because of its mind-bending structure. There is much to puzzle over after the film’s end. Whose subconscious were they entering? (Watch it again; it becomes clear.) Were those the same children at the end? (No, they were older and wearing different clothes.) Did that damn top continue to spin? (Well, that one’s not so cut-and-dried.) It’s this willingness to engage the mind — and the way that Nolan shows us worlds where city streets fold in on themselves, freight trains barrel through busy intersections, and hallways spin in space — that makes Inception more exciting than any close-call car chase could ever be. – Marisa LaScala

5. Winter’s Bone [Director: Debra Granik]

In a just world Winter’s Bone would be a frontrunner rather than a dark horse for the Oscars. Debra Granik’s film is a taut thriller about a young woman’s search for her father, a journey which assumes almost mythical dimensions as she ventures deeper and deeper into a menacing world of drug dealers and enforcers. At the same time Winter’s Bone captures the strength and resilience of Ozarks culture, incorporating many local people in the cast and taking great care to get the details right. Add in a stunning lead performance by Jennifer Lawrence, a host of strong supporting performances by, among others, John Hawkes and Dale Dickey, cinematography by Michael McDonough and music by Marideth Sisco and you’ve got a film which makes an indelible impression on the viewer. If that’s not a criterion for Best Picture, I don’t know what is. – Sarah Boslaugh

4. Black Swan [Director: Darren Aronofsky]

The almost-improbable quintet of Vincent Cassel, Barbara Hershey, Mila Kunis, Natalie Portman and Winona Ryder work like a finely-tuned muscle and are a pure thrill to watch in director Darren Aronofsky’s dark, visionary Black Swan. Right off the bat, with a magic dream sequence, the energy is unpredictable, dangerous. Within moments, several tricky themes are introduced: Nina’s infantilization by her Sphinx-like mother, Erica (Hershey), narcissism, sexuality, ageism, competition. Perfection. Women’s relationships to other women.

The most interesting theme to me was how one sees oneself, both in the mirror and metaphorically. Looking and being looked at, your every move being scrutinized is something that ballerina Nina (Portman) must learn to live with in the cutthroat world of professional ballet. In the film, she sees – and hates — herself and her doppelganger shadow self who peers threateningly at her from inside the mirror. Anton Walbrook-esque ballet director Thomas Leroy (Cassel) is deciding which of his ladies will replace the former prima ballerina Beth (a delicious Winona Ryder) as the Swan Queen and has his eye on Nina, but is unsure if she is free enough to transform into the ravenous Black Swan. Will the role go to the virginal pipsqueak Nina or her smoldering rival Lilly (Kunis)?

Aronofsky ups his game with Black Swan, with a firm command over the construction of the film and all of its elements. The director offers up a literate, emotionally-complex, and fascinating visual objet d’art that is intoxicating to simply sit back and watch, but also one that is almost even more exciting to deconstruct, debate, and interpret. – Matt Mazur

3. The King’s Speech [Director: Tom Hooper]

As entertaining as it is, as well made and proportioned as it is, The King’s Speech can’t help but suffer from some of the same source issues as many it its period piece pathway. Unlike The Queen, which carried a kind of deconstructionist post-modern demeanor to its narrative, we get the same old structures here, moviemaking mannerisms that launched a dozen Merchant Ivory epics. We can feel the implied weight of what’s going on here, how the characters’ struggles could actually lead to the end of the British empire as we know it.

Even during an ironic moment when a newsreel of Hitler catches the royal eye, there is still a stateliness that the rest of The King’s Speech is eager to overcome. When it does, it’s magnificent. When it doesn’t, we still enjoy the voyeuristic nature of the premise. In the end, however, when our royal lead learns to control his voice — and indirectly, his future reign — we are sold. The results speak for a beautiful, resonate masterwork. – Bill Gibron

2. True Grit [Director: Joel and Ethan Coen]

With a solid sense of humor and an eloquent way with words, True Grit is a joy on many levels. it’s adventurous and fun, yet isn’t afraid to deal in the deadliest aspects of its travails. The Coens continue to press the boundaries of art in entertainment, carving out a unique niche in cinema that, as of now, is yet to be matched. These men are marvels, looking at each new project as a chance to hone and expand their ample skill set. While no one would deny their ability to handle something like True Grit, what the Coens ultimately do with it is a revelation. Not only do they rip it from the well-earned celebrity attached to its formidable former star, they make us forget John Wayne all together. And when you consider the size of said legend, that’s quite an accomplishment. – Bill Gibron

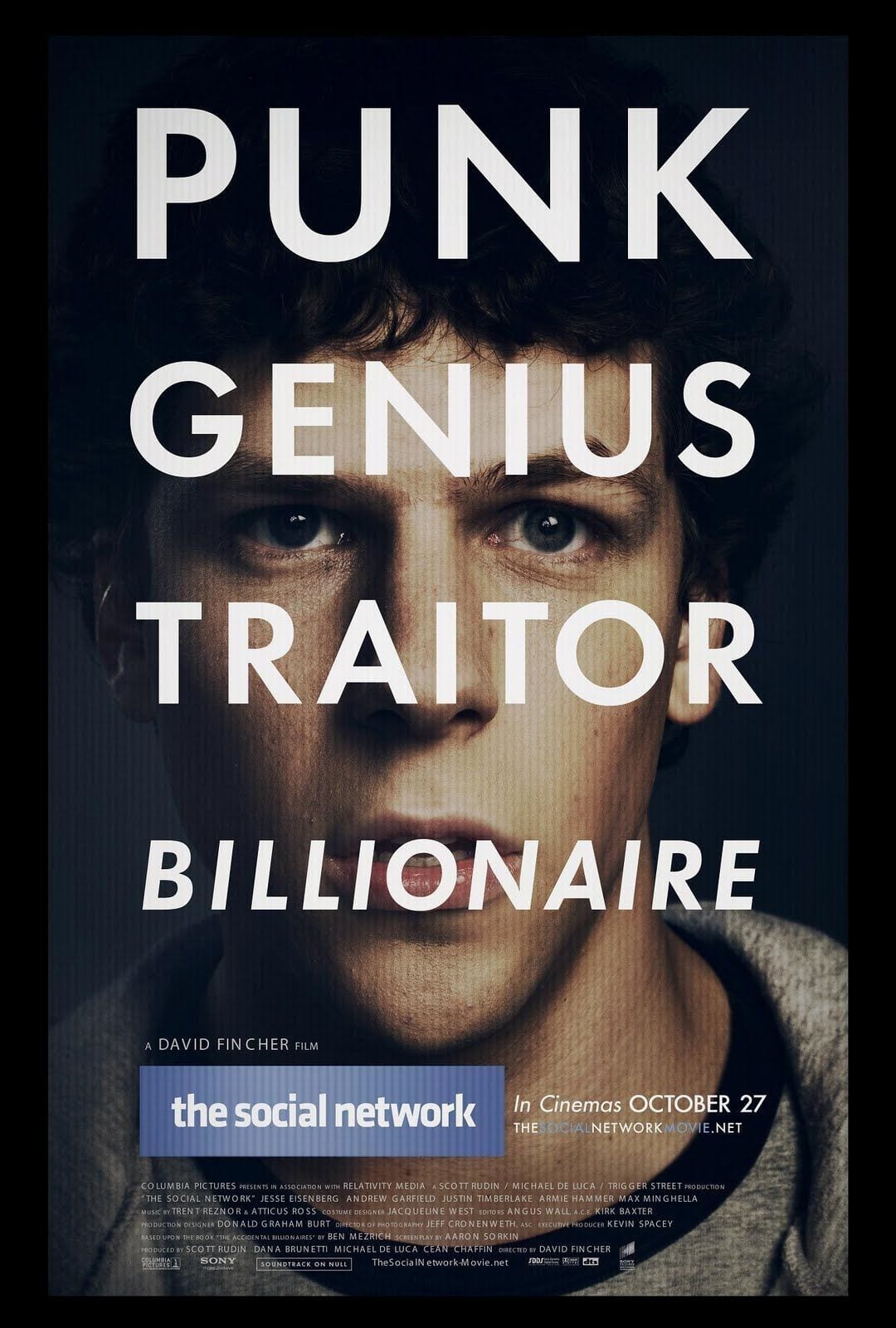

1. The Social Network [Director: David Fincher]

David Fincher’s foreboding dramatization of Facebook’s inception and expansion darkly suggests that the internet “revolution” has not nurtured the good in our souls, but only amplified our most primal driving impulses. The Social Network‘s thesis is that Facebook has not really made us more than we were, but made us more of what we are: striving, grasping beasts fighting for the limited space available to us and, just maybe, a few inches more.

Fincher expertly shoots Aaron Sorkin’s script of endless talkative wit as an ominous thriller, and lead actor Jesse Eisenberg plays the recently-minted Time Man of the Year Mark Zuckerberg as an obsessive, sharp-tongued misanthrope who gets to where he does not in spite of his anti-social tendencies but, indeed, specifically because of them. This is an arresting film that taps into not only the culture of the moment but also, more potently, the black energy inherent to the human character. – Ross Langager

* * *

This article originally published on 11 January 2011.